An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

When working on historical materials, one should first present a clear list of the periods under discussion. However, in these lectures, the necessity of explaining certain basic terms and concepts, and addressing the entries that form the basis of the topics discussed, has delayed this task, to the point where the proposal for the periodization of Iranian art and culture has been postponed to this article.

So far, in several lectures, we have addressed essential components such as the epic nature, or manifestations like the garden, and certain smaller motifs. The purpose of presenting these topics was to draw readers’ attention to the shared foundations of Iranian culture across the span of time and the lateral continuity of its diverse manifestations and products. All these discussions emphasized the characteristic of cultural ‘continuity’.

Now, we turn to the ‘ruptures’, focusing on what has transformed over time. These turning points have sometimes taken the form of epoch-making developments and the culture grappling with a new message, while at other times, they have manifested as the infusion of old meanings into new forms, or conversely, the continuation of old forms with the renewal of the meanings they carry.

As previously mentioned, the cultural nature of Iran is the result of the interaction between two forces: ‘becoming’ and ‘continuity’, or transformation and persistence. By examining each period of Iran’s long history, one can recognize the involvement of both these forces, which have both renewed and sustained. It can be said that the vitality and productivity of this culture have been made possible through the constant challenge and struggle between these forces.

The Era of the State of Culture

The first step in any kind of historiography, including the history of art, is to pay attention to the material under study in terms of its ‘difference’ from other cultures and to ask the question: where lies the distinguishing feature of our subject of study?

Efforts to apply established models from one cultural context onto different historical and cultural material, or attempts to overlook differences and present a universal model for humanity to explain phenomena under a single historical framework, remain rooted in pre-modern consciousness.

For the people of this culture, such a process might be seen as a self-evident and natural rule, universal and applicable to the history of all humanity. However, as mentioned in previous discussions, through the comparison of foundational cultures, we will notice differences—sometimes fundamental, sometimes subtle—that set them apart and ultimately lead to different behaviors and achievements.

In this lecture, our focus is on understanding historical periods, each of which has been separated from its predecessor by ‘epoch-making transformations’. Here, the span between two major ruptures in consciousness is defined as a ‘period’.

While we aim to identify breaks and transformations, this study will not be fruitful unless, during this exploration, we also keep an eye on the threads that have connected these periods. Research will not yield accurate results unless the researcher simultaneously tracks both the continuity and the transformation of a nature that constantly renews itself, growing fresh branches from its ancient roots.

The Importance of Applying Periodization to the History of Iranian Culture and Art, Especially Given Its Vast Temporal Scope, Lies in Several key Factors

In these lectures, it has been frequently noted that the continuity of historical life necessitates that a culture be able to name its past periods with contemporary awareness. On the other hand, ‘naming history’ is a capability that can only be developed within a cultural system; such a system carries its initial seed and its particular symbols of awareness, and has the potential to nurture its concepts and categories. This perspective is not only effective in addressing the self but also provides a framework for understanding the other—just as in the West, Oriental studies have served as a point of reference for naming and identifying civilizations outside of Europe.

In the previous lecture, some points about the logic behind this periodization and naming were discussed. For a reminder, here is a summary of the most important points:

• When planning the history of Iranian art, focusing solely on materials that can be categorized under the definition of ‘art’ will not be effective. Similarly, relying on categories such as ‘fine arts’, ‘decorative arts’, and ‘visual arts’, which have emerged in the evolution of European thought, is not relevant. Instead, a more comprehensive approach is beneficial, one that includes all achievements of ‘art and culture’ in Iran. This means studying and understanding the entirety of the Iranian cultural system and its manifestations, including literature, poetry, architecture, music, visual arts, calligraphy, theater, etc., rather than selecting only certain branches based on their alignment with the European art historical model.

When working on the history of Iranian art, focusing solely on selecting materials that fit within what is categorized as ‘art’ in Western history is not productive. Similarly, relying on concepts such as distinguishing ‘fine arts’ from ‘decorative arts,’ which are meaningful only in the context of European thought, is completely irrelevant here.

Instead, a more effective approach is to study and understand the entirety of the Iranian cultural system and its manifestations in literature, poetry, architecture, music, visual arts, calligraphy, theater, etc., and to provide classifications that are appropriate for these historical materials and their developments.

• In studying Iranian art, pursuing approaches based on ethnicity is misguided. Thus, focusing on theories such as ‘Aryan race’ and dividing periods into before and after the arrival of the Aryans can divert the research path. 1 This perspective generally conflicts with our understanding of Iran’s diverse cultural world.

Naming conventions such as ‘Persian’ and ‘Parthian’, as will be further explained, refer more to territorial areas where various ethnic groups have lived at different times, rather than to a single ethnic or racial group in the modern sense.2

• In naming, attributing periods of Iranian art history to ruling dynasties and political regimes is a mistake. Sometimes, these names refer to a family or tribe (e.g., Qajar or Safavid art), or even to invaders (e.g., Timur, Mongol, Seljuk), making the use of their names for an artistic style entirely inappropriate. Such naming conventions (e.g., Achaemenid art, Sassanian art, etc.) emerged in the modern era, primarily through the work of European scholars, and there is no historical precedent in our written sources to support them. 3

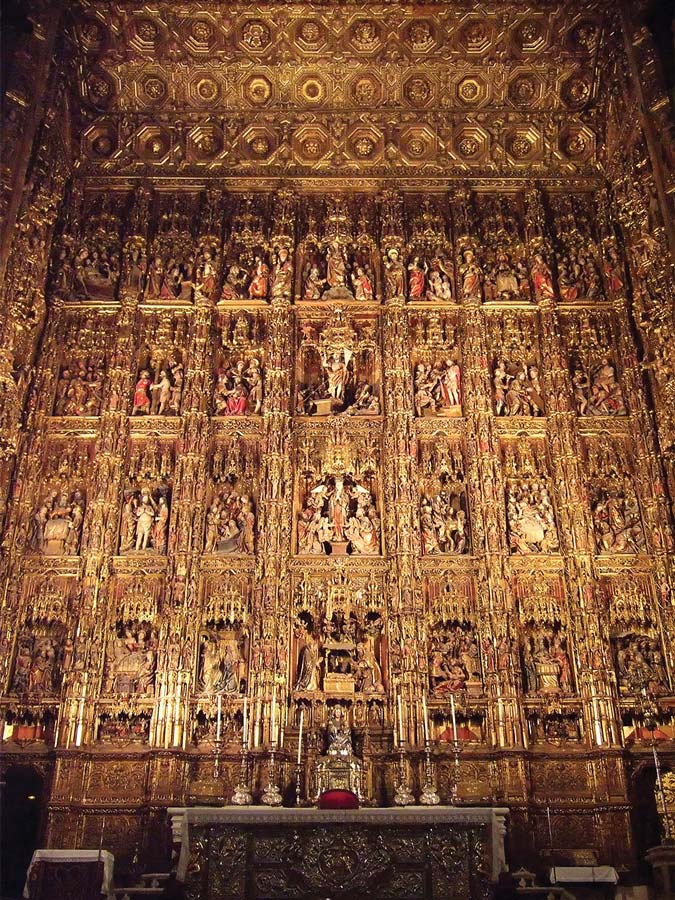

• Naming arts and periods after religions (e.g., Zoroastrian art, Manichaean art, Islamic art, Buddhist art) provides misleading connotations. These names are based on the relationship between religion and art in other societies, such as in the Christian Holy Roman Empire, where the relationship between religion and culture differs fundamentally from that in Iranian cultural society.4

• Dividing Iranian art history into ‘pre-Islamic’ and ‘post-Islamic’ periods distorts the study of the ‘Golden Age of Iranian Culture’ or the ‘Renaissance of Iranian Art’ in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries AH (equivalent to the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries CE) and disrupts the understanding of its connections with the preceding centuries.

• Using the term ‘Middle Ages,’ which is specific to a historical period in Europe, to refer to equivalent historical periods in Iran is incorrect, as this temporal division does not denote any particular characteristics in Iranian history. This term homogenizes important fluctuations in Iranian history during this period, some of which coincide with the Renaissance of Iranian culture.

• Studies that are limited to a single intellectual tradition or that follow only one text or cultural thread in naming and dividing periods hinder the understanding of Iran’s cultural diversity. Revealing the idea of unity in diversity is crucial here. Any research that accounts for different texts, as well as the simultaneity and layering of Iran’s intellectual history, can be effective. 5

We see the tradition of naming by attributing each piece to its place of origin in Iranian carpets, where the names of the carpets form a long list of the centers of production for this art.

• In researching Iranian art, attention must be given to the broader cultural geography of Iran. As recent texts suggest, if our explanations are limited to the political borders of contemporary Iran, many cultural achievements might fall under misleading labels such as ‘Uzbek art’ or ‘North Arabian art,’ thereby being completely excluded from this cultural system and losing their spiritual connection and significance.

• Certain linguistic categorizations, such as those explained by Europeans under the ‘Indo-European’ language family, can hinder understanding here. A significant portion of our intellectual heritage has been in languages outside this family (such as Arabic, Syriac, etc.). Regions within the Iranian cultural sphere (like Armenia, Georgia, etc.) have generally had different languages. It is important to consider these alongside the ancient national language of Iran, taking into account the three long periods of the Persian language: Old Persian, Middle Persian (Parthian and Sassanian), and New Persian.

• Referring to the naming conventions used in the history of literature, architecture, and political thought in Iran, it appears that cultural historians, drawing on their familiarity with the heritage of the past and aiming to convey the spirit of Iranian culture, predominantly used names of ‘geographical locations’ for naming schools and styles—such as the Khurasani School, Azari Style, and so on. These names do not imply that only the local people of a particular region were involved in creating that school or style. Instead, the choice of these names reflects the ancestors’ understanding of the complex and varied nature of thought and culture across different regions of the Iranian empire. Throughout Iran’s history, we encounter centers in various locations—whether broad areas, cities, or even villages—where schools, methods, and styles are named after them. 6 For various reasons, at each period, new intellectual achievements have concentrated in a central hub, which has acted as a womb for the embryonic idea of this culture and its shared aesthetic content. In this historical process, each time, based on previous shared achievements, a new school has emerged, leading to the development of an era, with styles and methods becoming apparent.

Naming arts and periods after religions—such as Zoroastrian art, Manichaean art, Islamic art, Buddhist art—provides a misleading interpretation of the history of Iranian art. These names are based on the relationship between religion and art in other societies, such as in the Christian Holy Roman Empire, where the relationship between religion and cultural identity differs fundamentally from that in Iranian culture.

Proposed Periods for the Study of Iranian Art History

In the study of the history of Iranian art and culture, five major periods can be distinguished 7:

- Formation: 10th millennium BCE to 1st millennium BCE

- Establishment: 8th century BCE to 2nd century BCE

- Integration: 2nd century BCE to 12th century CE

- State of Culture: 12th century CE to 18th century CE

- Modernity: 18th century CE to the present”

Aside from the long period of Formation, which has distinct conditions due to its antiquity, the remaining periods have seen the fruit of evolving awareness manifest in the form of schools and styles: during the Establishment period, the Persian school emerged; in the Integration period, the Parthian and later the Khurasani schools appeared; and in the State of Culture, multiple styles came to prominence.

This proposed periodization and understanding of schools is inspired by effective research previously conducted on the history of literature, as well as on architectural history and political thought. These studies, particularly across various branches, show significant alignment and mutually confirm and complement each other.

In the Formation Era, the Iranian world emerged with a character fundamentally based on the concept of generative honor. This trait, which can be considered as the activation of the feminine pole of the world, was deeply woven into the fabric of cultural concepts and remained with Iran throughout subsequent periods. It acquired such a fundamental role that one could say as long as it endures, Iranian culture continues to exist.

In seminars on Nietzsche’s thought, Jung refers to the concept of ‘Logos’ in European culture. According to him, Logos is the fundamental seed that has rooted itself in the spirit of European culture and has spread throughout all its aspects. Jung considers Logos as a masculine element that requires its counterpart, Eros 8, or the feminine aspect.

What Jung describes highlights a fundamental difference between Greek and Iranian cultures. Greek and, subsequently, European art has been shaped around the concept of Logos. The inclination towards creating dominant monuments, sitting in the ‘loge,’ observing, setting rules of perspective, and many other general and specific paths followed in Western art history all stem from the influence of Logos. In contrast, from this perspective, the nature of Iranian art aligns more closely with Eros. This is evident in its motifs and architectural designs, which result from the continuous proliferation of elements and the endless creation of motifs and spaces, where there is no room for the dominance of Logos.

From this viewpoint, one can understand how Western culture progresses by pursuing its opposite, engaging in a constant struggle with both its preceding tradition and the other. In contrast, Iranian culture has sustained its historical vitality through a method of accepting diversity, disseminating ideas, and integrating and adapting over time.

Explaining these paths does not mean ignoring the challenges and possibilities of failure. In the case of Iranian culture, the intensity and spread of conflicts, and their extension into new realms, have led to difficulties in maintaining its methods of absorption, integration, and continuity.

1. First Era: ‘Formation Era’; From approximately the 10th millennium BCE to the 1st millennium BCE

The initial chapter of the history of Iranian art can be recognized under the title ‘Formation Era.’9 This period, which coincides with the Agricultural Revolution, is the longest era in Iranian culture and is nearly three times as long as all subsequent periods up to the present. During this era, the Iranian Plateau was the stage for significant changes in human lifestyle and shifts in awareness, which not only impacted the fate of the cultural domain later known as Iranian but also transformed the broader human experience across the globe. This period marked the emergence of an idea that enabled settled life and food cultivation to prevail over other forms of existence and to spread across the four corners of the world. Thus, a new chapter in human history began, which, from a broader perspective, still encompasses our contemporary existence.

The Formation Era can be divided into two sections 10:

The initial section, from approximately the 10th millennium BCE to around the 5th millennium BCE, is characterized by universal human commonalities and the era of myth formation. The beginning of this period can be recognized by the gradual shift from cosmic awareness and the emergence of scattered forms of agriculture in the 10th millennium BCE. However, human life in this era remained largely under the influence of natural conditions.

The second section of this era can be considered as the stage where different types of awareness began to form in various communities. Differences influenced by climate and living conditions in scattered communities across the world’s landmasses and the separation from shared human conditions gradually became apparent from the mid-point of this period.

From approximately the 5th millennium BCE to the mid-1st millennium BCE in the approximate boundaries of the Iranian Plateau, a major shift in awareness occurred, and the mode of life distanced itself from mere dependence on nature. This period provided the temporal and spatial context for the development of the ‘Great Idea,’ which, as discussed in previous lectures, supported the scattered and previously unsuccessful efforts of agricultural experience, leading to the ‘Agricultural Revolution.’ This revolution rapidly spread across the world, traversing interconnected landmasses. This extraordinary expansion created the conditions for the continuity of settled life and food cultivation, dividing human history into before and after this period.

From this stage, Iranian myths began to show distinctions in content and nature from their older roots, diverging from the shared myths of other communities. On the other hand, the spread of culture and practices related to agriculture among the scattered cities facilitated greater convergence.

In a bit more detail: the second half of this period is characterized by the establishment of agrarian life in the cities and settlements of the Iranian Plateau. A key feature of this way of life was new strategies to reduce the damage from natural disasters and human conflicts. Major changes were primarily directed towards stabilizing life based on food cultivation, transferring acquired methods, and spreading the values that supported the continuation of this way of life to surrounding regions. Consequently, an ethical system emerged to ensure the survival of agrarian life, in which cultivating the land was valued and raiding and pillaging were deemed undesirable. The unification of farmers, through various means including the holding of joint agricultural ceremonies, significantly subdued war, conflict, and looting for an extended period.

The most significant tangible achievements of this period include the domestication of key animal species still in use today—such as horses, dogs, cattle, chickens, goats, and sheep—and the cultivation and improvement of primary cereal seeds. Important innovations also emerged in fire control and kiln techniques, leading to pottery and the extraction of metals and bronze alloys. These advancements facilitated significant leaps in tool-making, improved living standards, and the growth and complexity of cities and their internal and external relations.

Alongside these changes, a dualistic perception of existence began to replace the primordial shamanic deity. The idea of dualistic conflict provided a more conducive environment for intellectual debates. This period can be considered the beginning of the Age of Divine Wisdom and the formation of Zoroastrianism, during which a significant step was taken in the evolution of the mythological system towards epic thought. The Avestan language gradually acquired the capacity to convey ideas, as evidenced by its ability to present a structured collection of narratives in the Yasts. Considering the emphasized themes and the value system presented in the Gathas, which have a notable connection with the changing conditions of life during this period, it is likely that the foundation of this text was laid within this timeframe.

Notable evidence includes: the prohibition of sacrifices, encouragement of agriculture, emphasis on the value of working the land, and the promotion of the expansion of settlements. Moreover, the ontological framework presented in the Gathas carries significant shifts in consciousness that align with the transitions of this era: presenting a new conception of the beginning and end of the world, the grounding of celestial duties in the form of the Amesha Spentas, a new definition of the relationship between humans and existence, the establishment of wisdom based on the value of life and the immortality of the soul, the role of the Fravashi (spirit) and the introduction of the concept of Daeina (conscience), all of which are consistent with this mode of communal living.

The gradual changes of the Formation Era in Iranian history are significant in that, unlike European history, which considers its origins as inheriting changes from other cultural-geographical spheres, the Formation Era in this context occurred within the bounds of the Greater Iranian cultural realm—specifically the golden rectangle that places the Iranian Plateau at its center.

The cultural accumulation and continuous exchanges among numerous scattered communities reliant on agrarian lifestyles during the long Formation Era culminated in the emergence of a “historical society” by the end of this period.

The fundamental idea of agrarian life explained the cosmic order through a grand struggle between cultivation and destruction, death and life, goodness and evil. The ethics that could ensure the continuation of life in an agrarian society were based on human agency, the value of labor, encouragement for development, and reverence for fertility.

These shared elements led to the development of a new concept, that of “country” (from the root Karsh, meaning initially to plow or cultivate the land). Every piece of plowed land was seen as a sign of this “kinship.”

Additionally, traces of the earliest heroic epics from eastern Iran and narratives about the Kayanian kings, as well as the foundation of some of the earliest love stories that have been passed down and reworked in later periods, can be traced back to this era. Each of these contains various forms of the hero’s journey archetype.

From archaeological evidence and its reflection in epic narratives, it appears that by the last millennium of the Formation Era, after a long period of tranquility that provided a suitable environment for the development of culture in its various aspects, conflicts began to flare up once again.

It seems that the formation of the earliest agricultural festivals and their widespread celebration is associated with this period. The synchronization of agricultural communities for the observance of rituals depended on the adoption of a common calendar, which in turn required the expansion of astronomical observations. This practice of refining the calendar continued through subsequent periods with many significant efforts.

Additionally, from this era, the basic structure of society emerged, based on the differentiation of roles among the cultivators, warriors/heroes, and religious figures.

The transformation of consciousness during the Formation era and the spread of its ideas are most clearly reflected in the art forms, particularly in the pottery. In this context, the emergence of decorated pottery seems to be a fitting starting point for narrating the history of art and culture in Iran. These vessels, found with similar design patterns and a remarkable stylistic unity across a very broad area, represent the material remnants of the dissemination of the rituals that underpinned the widespread adoption of this new way of life. The distribution map of these pottery styles aligns closely with the map of the spread of this new way of life.

From archaeological evidence and traces in epic narratives, it seems that in the last millennium of the Formation Era, after a long period of peace that provided a suitable ground for the accumulation and development of culture in its various aspects, conflicts flared up again.

Some epic stories, such as the death of Zarir or the confrontation between Rustam and Esfandiar, which are reflected in later narratives, or the rites related to the death of Zoroaster that were performed until recent times, especially in Balkh, have very ancient roots in the Formation Era.

2. The Second Era: “Formation Era” From around the 8th century BCE to the 2nd century BCE, Persian School or Parsism School

The characteristics of the Formation Era were discussed in several previous articles. Here, for comparison with other eras, we present a summary of what was said:

Extended interactions, exchanges, and sharing of experiences from agricultural life led to significant convergence over a long period. A shared system of timekeeping, common rituals and festivals, and the emergence of widely used communication languages created the foundation for cross-ethnic alliances. Ultimately, the convergence of agricultural communities manifested in the formation of nations.

The establishment of countries or communal land ownership was based on this common foundation, and the concept of Iranian Land (Iranshahr) took shape, built upon the foundations of the agricultural life of the Formation Era and an ancient idea capable of expansion without the need for homogenization or eradication of differences—an idea that had been previously tested in simpler forms during the spread of agricultural life.

A new form of power establishment based on “unity in diversity” emerged. The first political system, in its historical sense, appeared in the form of the Persian Empire. This empire had unprecedented capabilities and resources for expanding its territory. Warfare, unlike earlier forms of invasion and plunder, now involved not only military defeat of opponents but also the administration of vast territories with diverse climatic conditions and cultures.

Creating a systematic and unified structure across such a vast territory, and achieving coordination among its diverse components, is possible through the design of modular structures.11 In the Persian Empire, the modular system creates a structure where each unit, known as a satrapy, is administered as a royal domain. Allied peoples and territories contribute to forming a “multiplex unit,” thereby ensuring a cohesive yet diverse empire.

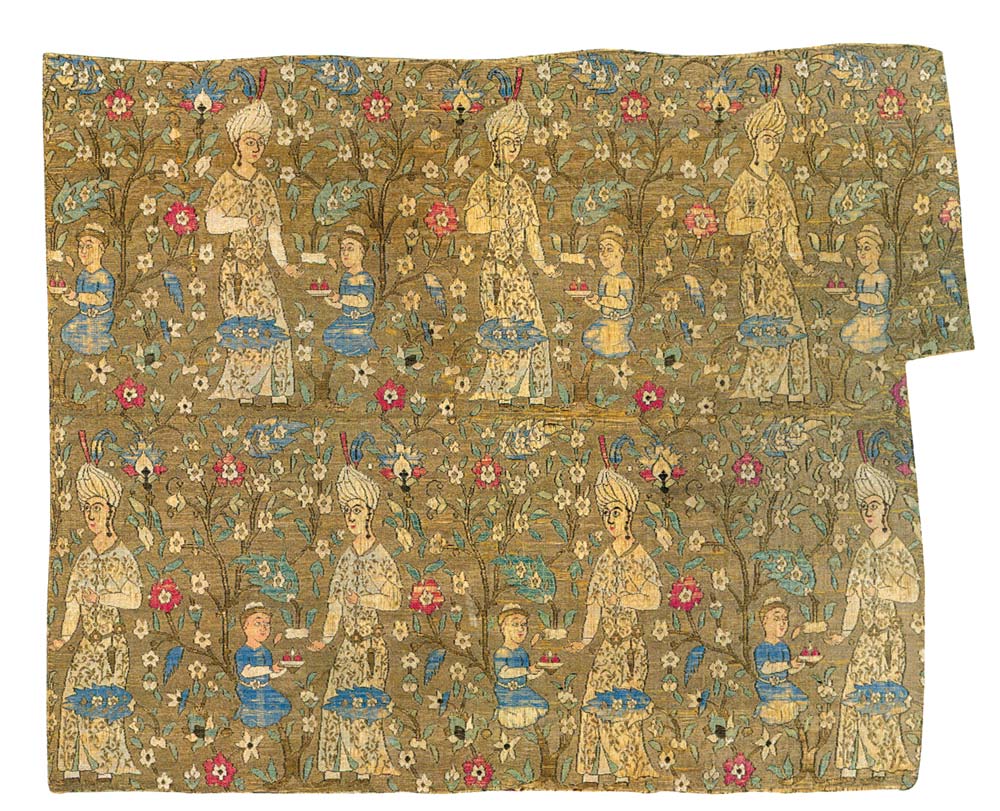

The modular logic is also evident in the more detailed design and formation of architectural elements and visual motifs. This organizational principle is reflected in the design of gardens and in recurring motifs, such as the early forms of later Islamic arabesques, and in the overall design of some surviving artifacts, including the Pazyryk carpet.

Garden design, which played a significant role in Iranian culture, is one of the achievements of the Establishment period. The fundamental structure of the Iranian garden, which consists of a land parcel enclosed with defined boundaries and organized based on modular divisions with water channels arranged in a cruciform pattern, has continued in its overall design up to the latest examples built in the 19th century.

In the art remaining from the Formation period, perhaps most notably the decorated pottery, with a remarkable stylistic unity, spread across a vast area corresponding to the expansion of settled life, represents the culture of the agrarian society and the new awareness associated with it. The motifs on these vessels reveal the relationship between humans and nature, the segmented and plowed land, domesticated animals, and a symbolic reference to the center and origin (measuring time and space).

These ceramics had ceremonial uses and indicate a type of ritual feasting that honored the capacity to cultivate raw materials from plants, animals, and clay.

“The long-standing tradition of decorated pottery, which began in the latter half of the seventh millennium BCE, was the primary manifestation of rural Iranian art for over three thousand years.”12

Gardens serve various functions, including facilitating dialogues and providing a context for transmitting a certain kind of wisdom. The Achaemenids constructed gardens wherever they went. Scholars like Bruce Lincoln 13 interpret the creation of gardens in newly conquered territories as part of the Achaemenid political development project. The presence in a garden, in a direct way, allows for an experience of a relationship with existence and makes the wisdom regarding human duties, which the garden is based upon, effective and comprehensible. Thus, constructing gardens is seen as a means of spreading this wisdom and a particular mode of being and living. From this perspective, the establishment of numerous gardens in Cappadocia, Greece, and other parts of the Achaemenid Empire can be understood as an expansion of the Achaemenid state.

In the Achaemenid era, as previously discussed, a “school” is established 14, thus the art of this period is not regional or ethnic but extends beyond cities and peoples, opening up to very broad horizons. The architecture of this period—referred to as the Persian School by Master Karim Pirnia—is designed based on a rectangular plan and central courtyard. Key features of this school include finely carved stone columns, colored facades, attention to geographical orientation (rūn), and the cycle of light. Some of the foundational elements of this school continued in Iranian architecture until the mid-19th century.

The urban planning features of this period focus on expanding the network of communication routes between centers, connecting them by land and sea according to the standards and mechanisms of a global civilization.

A significant achievement of the Persian School is the design of the first bureaucratic system or administrative organization, where establishing regulations for organizing affairs across various domains and diverse branches (such as public health) is emphasized.

Additionally, the calendar of festivals expands and develops on a global scale, with participation from peoples across the world; so much so that the influence of the Persian School can be recognized from some of the calendrical rituals that remain in the memory of distant peoples even today.

Historically, the language of this period corresponds with Old Persian, which also coincides with the standardization of Old Persian script. According to Gordon Childe, it is the first script based on phonetic representation. The historical inscriptions of the Persian School are almost all composed in multiple languages and scripts, requiring a significant translation bureau to render texts into various languages. These texts address all the peoples of the world.

In the global arena, the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire brought about a significant transformation. It created new relationships between scattered cities and local dominions, which, in comparison to the extent of this new empire, were much smaller. In human experience, a much broader horizon opened up towards geographical diversity, varied communities with different ways of life, moral norms, and beliefs. The unification of this unprecedented diversity under a single structure and organization required fresh ideas with far greater capacities.

The garden is one of the most significant elements that has maintained a unique continuity in the spirit and form of Iranian art. Existing evidence shows that its design in architecture, as well as its reflection in textiles (such as carpets), is an ancient heritage that dates back at least as far as the Achaemenid era. The Achaemenids undertook the construction of this garden model throughout their empire.

The Greeks, including figures such as Ctesias, Herodotus, and Strabo, reported on the prevalence of epic songs and narratives among the Iranians, indicating a continuation of the epic nature rooted in agrarian values.

3. The Third Period: “The Era of Synthesis”; From the 2nd century BCE to the 12th century CE. The Parthian School and the Khorasan School

From a political perspective, this time span—covering from the fall of the Achaemenid Empire to the arrival of the Turks in the 6th century CE—includes a transitional period of Seleucid rule, followed by the Parthian and Sasanian dynasties, then another transitional period with two centuries of Islamic Caliphate rule, and subsequently the attempts to establish national states such as the Samanids (in Greater Khorasan), the Buyids (in Ray and Iraq-e Ajami), the Saffarids (in Sistan and Kerman), the Ziyarids (in Tabaristan), and other smaller states.

This period can be called the era of amalgamation and fusion, characterized by the assimilation and intertwining of diverse cognitive traits and engagement with new texts. During this time, Iranian culture faced various issues, new questions, and numerous debates. The reflection of this accumulation and complexity is also evident in culture and art.

From a civilizational perspective, Iran during this period was a stage for major conflicts both in warfare and in intellectual arenas. Several significant defeats occurred on the battlefield; at least two major collapses—the Achaemenid and Sassanian empires—both happened within this era.

In the realm of culture, the outcome of this period was the increased amalgamation of Iranian culture with Greek elements and a deeper integration with ancient traditions. Although interactions with both cultures had a much older history, it was during this period that the engagement became more extensive and turned into an internal debate, resulting in the assimilation of these diverse traits. To better understand the situation, it should be noted that these internal challenges were occurring simultaneously with grueling external battles on the field.

During this period, the world takes on a new face in various aspects—trade routes, military formations, technology, and even clothing—maintaining these relations almost until the Industrial Revolution. On the global stage, powerful “others” emerge who are inevitably in conflict. In China, roughly contemporaneous with the rise of the Parthians, a central government emerges that unifies the land of China for the first time and steps into the arena as a major power. In the West, Rome rises, contrasting with the city-state culture of Greece that was confined within its limited sphere and expanding outward.

Professor Karim Pirnia’s use of the term “human-like” to describe Persian architecture highlights its focus on human scale and functionality. This contrasts with the monumental and less human-centric design of structures like the Egyptian pyramids, the Parthenon, or ziggurats like Chogha Zanbil. The architecture of Persepolis, while grand, is designed with human proportions and movement in mind.

Persepolis, or Takht-e Jamshid, was constructed as a “festive space” with doors open to all nations. During this period, holding festivals and performing shared rituals contributed to the cohesion of a common world. One of the significant remnants of the Persian School that reflects its spirit is the depiction of all the nations of the contemporary world, along with their crafted goods and useful animals, on the walls of Persepolis.

On the other hand, the invading Turkic tribes also emerged on the scene of power: the first military alliance in the world to prevent the invasion of the Huns was established between Iran (the Parthians)15 and China. This treaty, which acted as a barrier against the advance of these tribes into the borders of Iran and China, pushed them towards the western lands, leading to severe consequences in Eastern Europe.

The world of this period witnessed significant cultural migrations related to the emergence of missionary religions: Christianity, Buddhism, Manichaeism, Mithraism, official Zoroastrianism, and Islam. Some of these are branches of ancient cultures, while others are products of the amalgamation of different cultures, each generating waves of significant relocations.

The written preservation of older sacred texts, or in other words, holy histories such as the Upanishads and the Old Testament, serves to further their dissemination. In other words, the act of recording these texts arises from the need to propagate them more widely and participates in the competitive nature characteristic of this era.

In Iran, these prolonged and diminishing conflicts also contribute to the consolidation of heroic qualities and the strengthening of wisdom in various fields.

In the cultural landscape of Iran, we witness the simultaneous development of heroic, philosophical, religious (in the sense of Dæna), legalistic, ascetic, and mystical qualities. In such an environment of internal tension and intellectual disputes, we can see the emergence of significant figures, some of whom seem to epitomize one of these traits. Figures like Farabi (3rd century AH), Ferdowsi (4th-5th century AH), and Al-Ghazali (5th-6th century AH) can each be viewed, with some flexibility, as representatives of specific intellectual currents within Iranian culture. Over this period, there is a process of synthesis and integration, leading to the gradual emergence of personalities and works that intricately reflect the blending of multiple cultures.

In fact, the fusion of these natures leads to the emergence of figures who each embody a unique multidimensional existence and cannot be attributed to a single text or cultural domain. For example, Avicenna (10th-11th century) is a novel phenomenon: he amalgamates Aristotelian philosophical thought, epic wisdom, Iranian angelology (especially in al-Shifa), and Gnostic ideas (which themselves are a blend of several natures) into his character and thought. Avicenna is not the only representative of this composite nature; figures like Suhrawardi (12th century), Al-Biruni (10th-11th century), and other greats of this period also belong to this category. The common trait of these great figures is that they seem to have emerged from a cocoon, possessing a vision much broader than before.

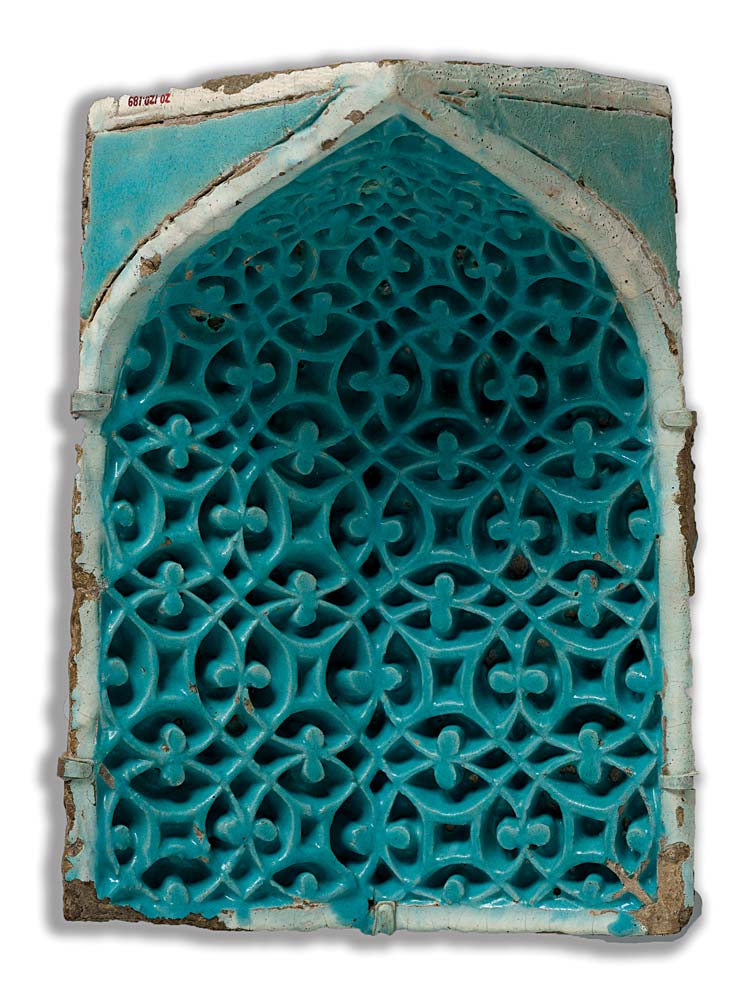

In contrast to the motifs of the Persian School, which were created through the juxtaposition and repetition of static, flat patterns like the twelve-petal flower or lily, during the Period of Fusion, the Parthian and later Khorasani Schools developed motifs that create fluid patterns with multi-layered compositions. These patterns seem to weave and intertwine, appearing to move between the surfaces and depths.

In the subsequent period, it seems that this feature becomes more apparent, with the emergence of characters such as the dervish, ascetic, philosopher, and jurist reflecting a differentiation in heroic ethics, moral ethics, and jurisprudential ethics in the social sphere.

This trend of increasing layers or, in other words, multidimensionality is traceable in visual arts, architecture, and literature. In Persian literature, the capacity of words to carry multiple meanings increases significantly. Similarly, motifs that were predominantly flat or single-plane in the Persian School become multi-layered in this period’s art. Unlike the motifs of the Persian School, which were created by juxtaposing and repeating static, flat patterns like the twelve-petal flower or lily, the designs of this era feature intricate, multi-layered compositions. The patterns seem to intertwine and move between surfaces and depths. Thus, by the end of this period, secondary motifs emerge from the interaction and overlap of primary elements. The proliferation of layers in architectural design also becomes notable.

In this period, two schools emerge: the first is the “Parthian School” and the style known as “Sassanian,” which we refer to as “Neo-Persian,” spanning from the 2nd century BCE to the 9th century CE. The second is the “Khorasan School,” from the 9th century CE to around the 12th century CE, which can be considered a renaissance of Iranian culture.

Parthian School or School of Parthia

The 3rd century BCE marks the end of the Achaemenid Empire and the beginning of Seleucid rule in Iran. Considering the preliminary events, this period represents a historical cycle reaching its decline and descent. A rupture occurs that simultaneously carries the seeds of future developments. The re-flourishing takes almost two centuries (a similar experience of decline and subsequent reconstruction occurred again after the fall of the Sassanian Empire, which Abdolhossein Zarinkoub referred to as the “Two Centuries of Silence”). This two-century interval was spent digesting new texts, rebuilding, and focusing on “transferring the battle from the field of invasion to the realm of thought and culture.” This shift to the cultural front ensured the continuity of Iran, to the extent that, as will be explained, gradually the burdens left behind in other domains also began to overflow into the cultural sphere.

There are noteworthy parallels between this ancient period and the millennium that followed.

Although Alexander is referred to as “Gujastak” (accursed) in some Iranian sources and the destruction wrought by the Macedonian army and the plundering of Iran’s historical treasures are recorded in the texts, the Alexander romances reveal another aspect: a dialogue in the realm of wisdom between the Iranian and Greek intellectual spheres, with Alexander symbolically representing the carrier of wisdom.

In both of these periods, at the end of the Achaemenid and Sassanian empires, a historical peak was followed by a period of decline. In such situations, survival depends on the ability to renew thought and devise new plans. Within the Persian school, there was a reciprocal dialogue between the Iranian world and the Greek lands. Although Iran suffered a major defeat, the outcome of the struggle was not determined solely on the battlefield; success in the realm of thought and culture, with an idea that could ensure cultural continuity and be fertile in intellectual domains, played a crucial role.

During the two floating centuries between the end of the Persian school and the beginning of the Parthian school, the Seleucids, despite the migration and settlement of populations in Iran, were absorbed into the gravitational field of the Iranian cultural system. On the other hand, these large migrations emptied the Greek lands, which were then handed over to the incoming Romans; this marked the end of Greece. The historical seeds of the Persian school had such potential that the encounter with the Seleucid invaders, building on previous dialectical foundations, led to the emergence of an “Iranian-Greek” synthesis. This character took root so deeply that it can be considered one of the significant components of Iranian culture to this day.

The parallel conditions at the end of the Sassanian rule are also noteworthy, as they were marked by crises that necessitated intellectual renewal. Beyond the records of confrontations with Manichaeans, Mazdakites, and others, signs of crisis are evident in the coronation speeches of the kings, as recorded in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh.

The language of this period is Middle Persian, which evolved into two forms: Pahlavi and Sassanian. Writing was done using the Pahlavi script, with seven variations employed for different purposes. This script continued to be used for centuries after the advent of Islam and had a significant influence on the design of scripts following the Kufic script.

In addition, in the Parthian school, the older tradition of using multiple scripts and languages continued. During the Parthian period, texts were written both in Pahlavi script and Greek, and this practice persisted into the Sassanian era. Most documents from this time were composed in Pahlavi, Greek, and Syriac. Additionally, the translation of Sanskrit, Greek, and Syriac texts became notably widespread.

During the reign of Artabanus IV of the Parthian dynasty (circa 2nd century CE), there was a focus on collecting and redacting the Avesta and rewriting ancient epics, all of which were undoubtedly reorganized based on the knowledge of the period. New stories were also composed in the form of heroic epics and romantic (romance) epics.

The defining feature of the “Era of Fusion” (2nd century BCE – 12th century CE) is the blending of multiple natures. During this period, Iranian culture engaged extensively with Greek and ancient cultures, leading to their integration and amalgamation.

Thus, it is not surprising that during this time we witness the simultaneous emergence and growth of epic qualities, rationalism, philosophy, religious devotion (in the sense of dēnā), jurisprudence, asceticism, and mysticism. As the initial tumult settles, it seems that these characteristics come into consciousness. The appearance of characters who are mystical, ascetic, philosophical, and legalistic in literature reflects a certain degree of differentiation between epic ethics, moral ethics, and jurisprudential ethics in the social arena.

From this perspective, one can re-examine Rumi’s words at the end of this era when he sings, “I am half from Turkistan, and half from Fergana.”

As briefly mentioned, a key feature of this era is the expansion of cultural migrations. If the initial migration of humans from the African continent, known as the “Great Migration,” was driven by the need for survival and the search for food, this period is marked by various large-scale migrations motivated by intellectual, religious, and cultural reasons.

During this era, Narseh, a Parthian prince from Sogdiana, travels to the land of “Pali” in northern India. He is the first to collect Buddhist texts or the sayings of Buddha. He then migrates to China and becomes a missionary for Buddhism, which comes to be known as “Mahayana Buddhism.” In eastern Iran, Buddhism spreads, and numerous Buddhist temples are established in Balkh and Kashmar. The Sassanian Espahbod family of Ishtarons also converts to Buddhism. A lasting legacy of the widespread adoption of this religion in Bamiyan, Balkh, was the colossal Buddha statues, which stood until their destruction by the Taliban.

On the other hand, Mithraic traditions make significant inroads into the Western Roman territories. With the missionary migrations of Mithraic followers, a blend of Iranian and Buddhist religious ideas, rich in themes of love, salvation, and human liberation, spreads across Greek-Roman lands. The fusion of these new themes with the Old Testament leads to the creation of the New Testament.

Some scholars have noted the fundamental differences between the spirit of the Old Testament and the New Testament, raising questions about how the text could shift so markedly from anger to love. Particularly, there is interest in the similarities between the New Testament and Buddhist Sankhya texts. Zabih Behruz has pointed out that this influence is mediated through Iranian culture.

During this period, a group of musicians known as the “Gypsies” migrate from the Indian subcontinent to Iran and later spread to various parts of the world in about sixty branches. Traces of this migration are preserved in the Romani language. 16

In the Persian School, urban design continued to follow the ancient patterns of Elamite fortresses and ancient cities. This design evolved in the Parthian School, where cities expanded significantly in number, although their wealth and power did not match the peak of the Achaemenid period. Consequently, creative and innovative solutions were developed to address various constraints and changing issues.

Architecture in the Parthian School differed significantly from the Persian School, which was characterized by the use of finely carved stone and flat roofs supported by columns and platforms. In contrast, the Parthian School utilized cheaper materials like rubble stone and introduced innovations in construction materials. For example, a type of mortar (bitumen) was made from a mixture of semi-cooked gypsum and lime. With the solution of two-variable equations and advancements in elliptical geometry, domed roofs with elliptical and double-centered arches were developed, providing significantly higher resistance to pressure and seismic activity in earthquake-prone areas.

This method of arch construction brought about a fundamental transformation in world architecture and opened a path in Iranian architecture based on the interplay between the circle and the square, a tradition that continued uninterrupted until modern times. The legacy of this school, along with significant advancements in construction techniques, gave rise to the Khorasani School, which spread extensively throughout the Islamic civilization and also influenced the development of Gothic architecture beyond this realm. In the Parthian and Khorasani architectural schools, a new general framework for building design was introduced, later known as Architecture Nervure.

Religious pluralism is a significant aspect of the social reality during the era of amalgamation. Both Sassanian kings, Bahram II and Shapur II, were of Jewish descent through their mothers, as Jewish law dictates that religion is inherited from the mother. The king himself held simultaneous Zoroastrian and ancient beliefs, a phenomenon not unique to him; a substantial portion of Iranians adhered to various branches of Christianity. Nestorian Christianity established important churches in Merv. This religious pluralism encompasses numerous branches, some of which can be categorized under major groups like Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Abrahamic Christianity, Mithraic Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam, all of which were in contention until the era of the Eighth Imam.

In such a context, there are reports of religious persecution under the Sassanian rule. Some of these tensions can be explained, for instance, by the rapid spread of Manichean and Mazdakian ideas, which were based on the denial of the inherent goodness of the world and promoted monastic practices in opposition to the importance of labor for the world’s prosperity. In a region where securing water required generational effort, these ideologies were seen as a threat to collective survival and led to significant devastation.

On the other hand, in the ancient cultural realm, “faith” wielded a sword, creating a dangerous mixture of ideologies. This was exacerbated by the fact that the central government in Iran was grappling with numerous internal issues.

The role of geometry in the Parthian and later Khorasani schools became increasingly prominent in both architectural space design and motif design. This was a result of revolutionary advances in algebra, geometry, and trigonometry.

Simultaneously with wars, migrations, and shifts, geographic knowledge also expanded. Additionally, from a trade perspective, commerce evolved into a more global concept. The visual motifs of the Parthian school, especially through the trade of textiles, spread widely and were woven in weaving workshops spanning from Egypt to Rome and China.

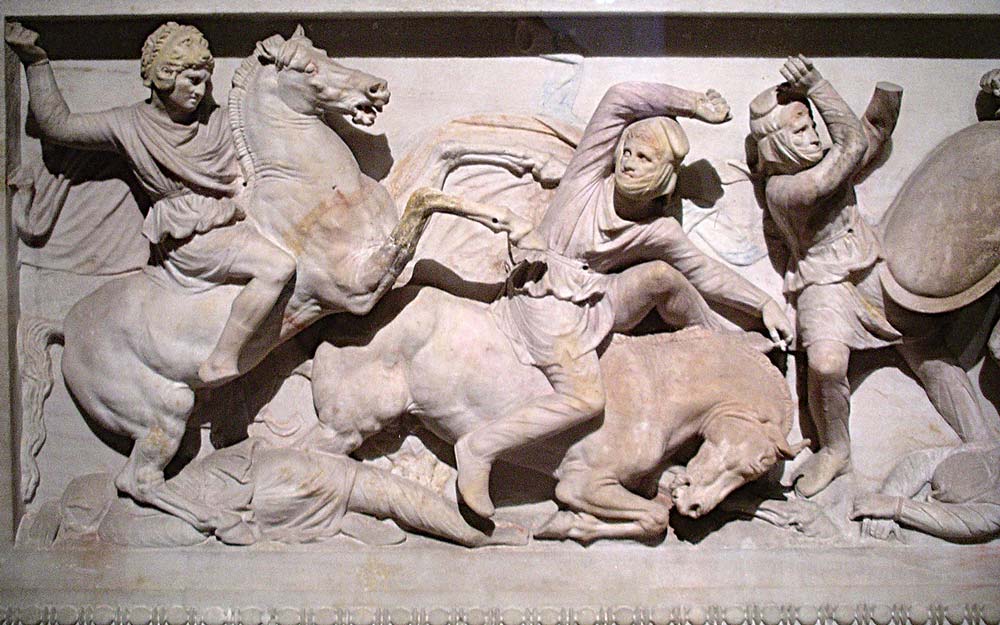

In the early Parthian period, the influence of Greek culture is more distinctly traceable. In other words, the dominance of Greek logos in the art of this period is easily identifiable. Over time, the process of cultural blending, and the absorption of Greek traits into Iranian culture, progresses such that the axis of Eros, or simply femininity and creativity, becomes more prominent.

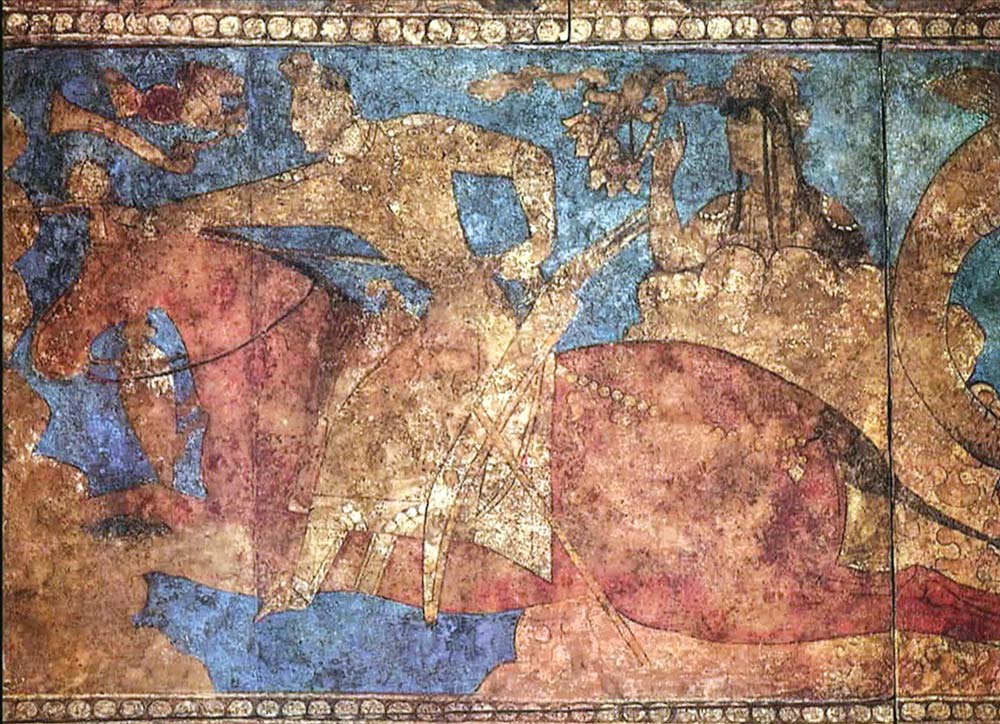

The visual patterns of the Parthian school, especially in their layering of asynchronous elements and the leveling of different realms, differ from those of the Persian art. Parthian bas-reliefs depict scenes that focus on specific perspectives and more detailed events compared to the broader views of the Persian school, moving closer to earthly existence.

Changes throughout this period involve transforming grand archetypes and patterns into forms and themes that emphasize detailed individuality and earthly characteristics. This evolution is observable from the formative period through the Persian school, then the Parthian school, and subsequently the Khorasani school. However, the direction of changes after the Parthian period does not continue along the same path; especially with the end of this period and after the Khorasani school, culture again shifts towards abstraction in various dimensions.

10th century CE / 4th century AH, Era of Synthesis

In ancient Iranian texts, the Parthians and the Sassanids were not distinguished with the precision that Nöldeke and Christensen have described. During the Sassanian rule, the title of Shahanshah was transferred from the Parthian Arsacid family to the Pahlavi family of Pars. However, the system of the Waspuharan and Aspbedan continued, with four of the seven major Aspbedan families adapting to this change. Even the Arsacid family in Armenia (the Arsakunians) did not depart from the historical treaty of Iranshahr. For instance, after a two-century interval between the Parthian and the Khorasanian schools, the Samanids considered themselves the successors of the Arsacids and the Buyids as the continuers of the Sassanids. It is noteworthy that only in Iran did national states re-emerge outside the Islamic Caliphate.

Under the Parthian visual school, a branch emerged known as the “Sassanian style,” which we propose to term “Neo-Persian” here. The continuation of this style in the Khorasani school paved the way for a wide variety of visual motifs in future styles.

From the music of this era, names like Pahlbad, Barbad, and Nakisa are preserved as prominent figures in the art according to historical accounts. The transformations of the Parthian school led to the establishment of the unique style of the Organian family under the Khorasani school, which will be discussed further. This music, along with poetry, carried a treasure trove of epic narratives, romantic epics, Khusrawian rites, and legends.

Simultaneously, it seems that the transformation from the threefold to the fourfold administrative system became significantly established across various aspects of culture and society. 17 This transformation is also evident in the civil system of Iran and the division of social classes.

Khorasani School / Khorasan School — Cultural Renaissance of Iran

After the fall of the Sassanids, a two-century gap between the Parthian and Khorasani schools marked the emergence of a third intellectual framework in the evolution of Iranian culture. Based on earlier interactions with Ancient culture, this new encounter led to the formation of an “Iranian-Islamic” narrative, which resulted from the blending of Ancient culture with previous texts, namely “Iranian” and “Greek.” From this transformation, a cultural renaissance emerged in the form of a school that was associated with the Khorasan region, a place insulated from intense conflicts. The unification of the Caliphate’s domain provided a conducive environment for the spread of this school to the farthest reaches of the Islamic realm, from Andalusia to China. What is contemporarily labeled as “Islamic art” is the result of the Khorasani school’s achievements or its fusion with neighboring cultures.

Researchers such as Richard Frye have identified the achievements of the Khorasani school as so significant that they refer to the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries CE (3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries AH) as the “Golden Age of Iranian Culture.”

A summary of these characteristics is as follows: The administrative system of the Khorasani school, continuing the order established until the Sassanian era, was founded in the newly established city of Baghdad, near Ctesiphon, by Iranian scribes, including the Zadanfarrokh family and their son Mardan Shah, the Barmakids, and the Noubakhtis.

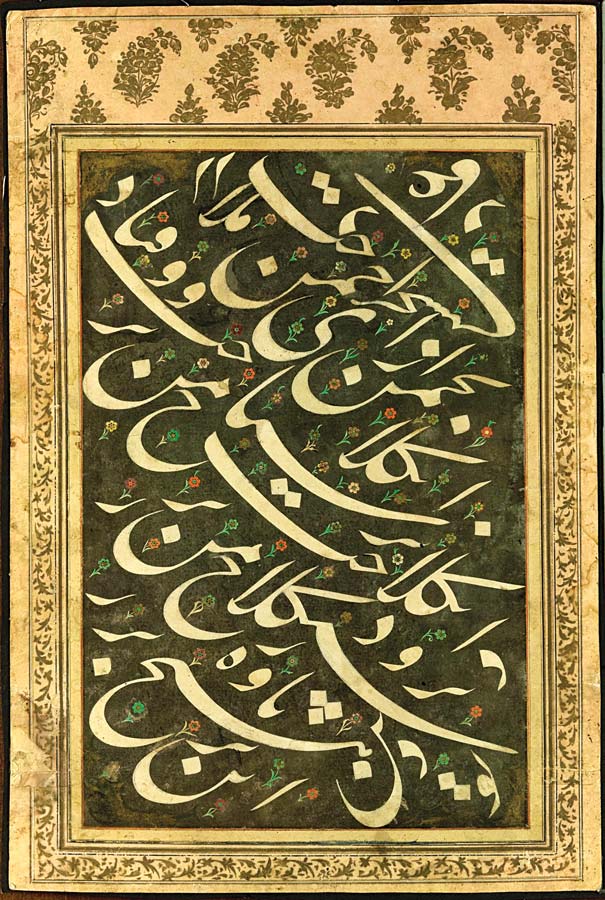

It was necessary to work seriously on the orthographic rules of the Arabic script and language. The early calligraphers and Iranian scribes, such as Ibrahim of Sistan, known as Ibrahim Shajari, invented a new style of Kufic script. Ali ibn al-Parsey al-Baydhawi, known as Ibn Muqla, a prominent scribe from Baydhawa in Fars, organized the six canonical scripts. These six scripts, in the tradition of Pahlavi writing, were each designed for specific uses.

Although for other peoples under Islamic civilization, association with the pre-Islamic era was considered disgraceful, Iranians never referred to their past as the “Age of Ignorance” (Jahiliyyah). On the contrary, in numerous instances, the most important Persian texts recall figures like Fereydun the Fortunate, Anushirvan the Just, and other ancient rulers and heroes endowed with divine grace as symbols of free thinking and measures of justice.

The Parthian School reached a level of richness and influence such that others began to replicate its motifs and relied on the semantic framework behind these designs, borrowing it to express their own ideas.

For the first time, Abd al-Hamid al-Katib established a system for composing and writing Arabic prose. Sibawayh, a Persian scholar, set the rules for Arabic grammar and syntax. The work of these great scribes, who were heirs of the Parthian School, created standards for eloquent Arabic, transforming it from a natural language with multiple, diverse dialects into a language capable of conveying nuanced meanings and ready to serve as a medium for science and culture. This language became a vessel for transmitting the intellectual treasures of Iran to the Khorasani School. Simultaneously, a movement for translation into Arabic emerged, with figures such as the great scholar and translator, Ruzbeh Purdadewiya, known as Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, carrying forward the heritage of the Parthian School to the Khorasani School. Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, by translating around 150 titles of Iranian texts into Arabic, preserved an invaluable heritage that was at risk of complete destruction.

During this period, great scholars in geometry, mathematics, and astronomy emerged. Buzjani was a prominent figure in geometry and trigonometry. Abu Rayhan al-Biruni was not only a leading scholar in these fields but also excelled in linguistics, botany, mineralogy, and geography. Both Biruni and Buzjani made significant contributions to astronomical tables (zij) and the refinement and updating of calendars, and they collaborated on noteworthy projects for observing and measuring geographical distances. Biruni calculated the Earth’s circumference with relatively minimal error.

Zakariya al-Razi made significant advancements in experimental science and represented a view that placed human reason in the highest regard. He was a well-rounded scientist in chemistry and pharmacology and is noted for founding some of the earliest hospitals resembling modern definitions in Ray and Baghdad.

Avicenna (Ibn Sina) solidified “clinical medicine” with his work The Canon of Medicine (al-Qanun fi al-Tibb) 18, which is based on observation and experimentation. His methodology gained widespread acceptance and continued to be referenced for over a millennium.

Another dimension of the work of the great scholars of the Khorasani school is reflected in their contributions to philosophy and wisdom. Foundational thinkers like Al-Farabi and Avicenna, each inheritors of multiple intellectual traditions, synthesized these traditions into new combinations. Through the integration and fusion of philosophical texts, a new philosophy emerged, later known as “Islamic philosophy.”

Among the achievements of this period in wisdom and philosophy was the development of a new approach to explaining and interpreting philosophical intentions in urban contexts. Avicenna, in his Book of Healing (Kitab al-Shifa), which includes his philosophical and scientific ideas, authored a treatise on natural music, while Al-Farabi wrote an independent and detailed work called Al-Musiqa al-Kabir (The Great Book of Music) on music.

The Arghani family, renowned musicians from the city of Argan (modern-day Behbahan), moved to Ray and, in conjunction with the musical heritage of the Janviyah family from Ray, made significant innovations in vocal and instrumental music. Mahan Arghani, known as Ibrahim al-Mawsili, and his son Ishaq al-Mawsili were founders of the Khorasani musical school. The transfer of this school to Baghdad in the 9th century significantly influenced the development of a style of music that spread throughout the Islamic world. This musical tradition was also introduced to Al-Andalus by the great Ziryab, a student of Ishaq al-Mawsili.

Ibn al-Haytham’s innovations in the construction of the camera obscura and astronomical image recording, beyond their scientific significance, laid the groundwork for entirely new methods. The transformation in the visual system in Europe was influenced by the new perspectives he opened, which fundamentally altered the realm of human imagery and imagination.

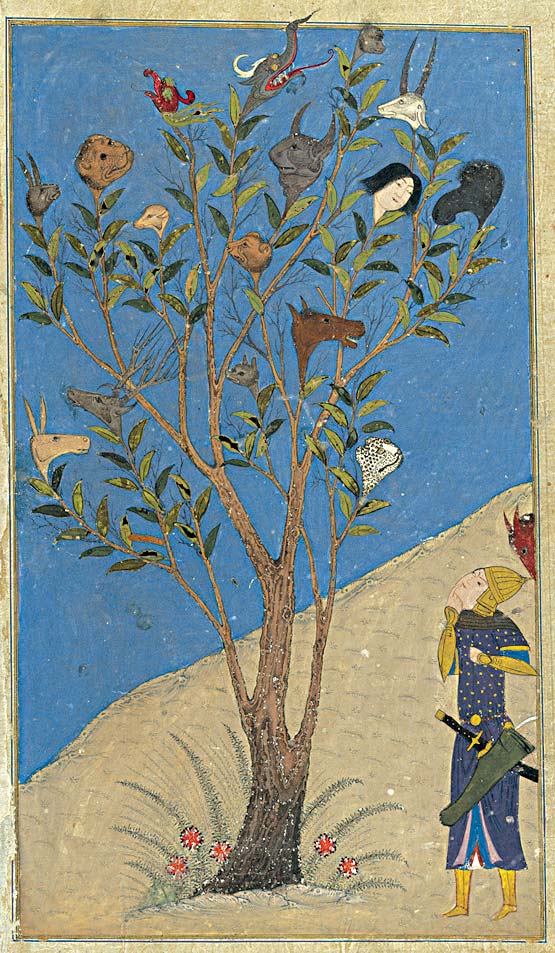

In the field of visual arts, the motifs from this period can be seen in the ceramics of Nishapur and Ray, the frescoes of the daughter of Khosrow in Panjakent, Turfan, and the motifs of Samarra. These artifacts demonstrate the continuity of the New Persian (Sassanian) style influences in the Khorasani school.

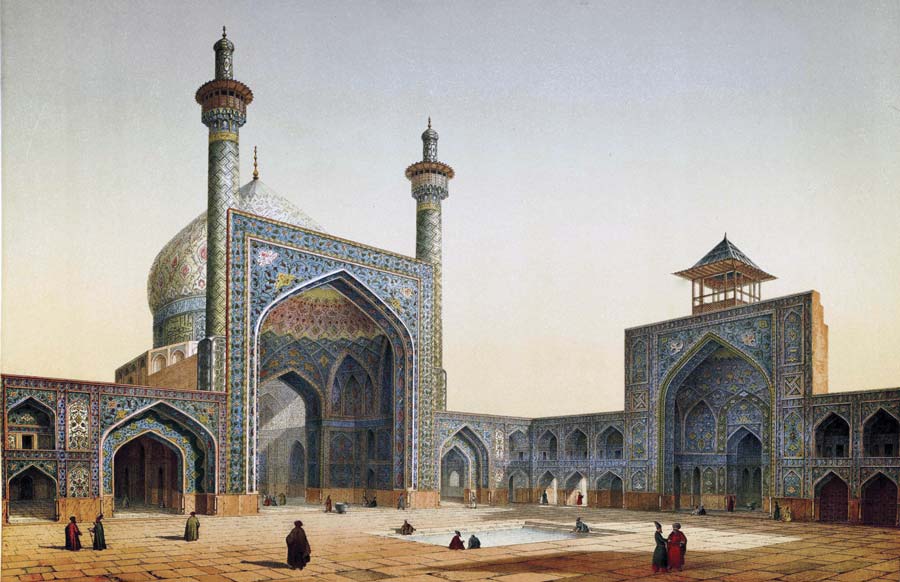

In architecture, the invention of the four-iwan design marked the culmination of the Parthian architectural heritage. The Khorasani school emerged as the most cohesive architectural tradition in the Islamic world and surrounding civilizations for nearly a millennium. Prominent architects of this school include Master Abu al-Hasan (builder of the Ribat-e Sharaf), Master Ali the Plasterer (Mosque of Faravahr), and Abu Zayd Kashani.

Within the Khorasani school, the heroic spirit was revived. In this respect, the works of this school, by activating a memory of the past in a new and modern form aligned with the awareness of the time, shaped the future of Iran—this is the essence of renaissance. The Khorasani school also provided the foundation for the emergence of the “New Persian” language, which, according to scholars, is the oldest modern language in the world.

According to the records provided by Ibn al-Nadim in al-Fihrist, the evolution of the Persian script and language can be traced back to at least the late Sassanian period. Under the Khorasani school, Persian new literature emerged through the work of intellectuals and literary figures, evolving to carry the cultural and intellectual attributes of its time. The literary heritage of the Parthian era was refined and transferred to the new Persian language, enhancing its ability to convey meanings and nuances more effectively.

The Parthian School was foundational in architecture, introducing dome ceilings with elliptical arches that provided greater resistance to pressure and earthquakes. This method of vaulting brought about a fundamental transformation in global architecture and established a path in Iranian architecture based on the interplay between circle and square, continuing uninterruptedly into the modern era.

The legacy of this school, along with significant advancements in construction techniques within the Khorasani School, flourished and spread throughout the Islamic world. It also influenced the emergence of Gothic architecture beyond this realm.

A substantial number of terms related to ceilings and domes in various languages are rooted in Parthian terminology, reflecting the pioneering nature of Parthian architecture and its widespread influence on neighboring cultures.

The national epic of the Shahnameh simultaneously contains both the ancient historical spirit and the new ethos of the Iranians during the period of amalgamation, and its composition in the new Persian language not only revived the past but also shaped the future of Iran.

The composition of the Shahnameh was completed at the end of the period of amalgamation. This time coincided with the beginning of the decline of national states and the power vacuum left by military leaders such as Abu Mansur Abd al-Razzaq from the esteemed lineage of Khorasan. Ferdowsi lost significant patrons who could have supported the reproduction of this work; however, the fame and popularity of the Shahnameh spread so quickly that only thirty years after its completion, the great Azerbaijani poet, Qatran Tabrizi, praised this national epic in his own poetry. 19

With a century and a half having passed since the beginning of the fourth period, which we have termed the ‘State of Culture,’ a powerful movement opposing the national heritage emerges. This movement not only conflicts with ancient epics and memorials but also attacks the rationalist spirit of Iranian culture. A faction of followers of the Ash’arite school, led intellectually by Imam Muhammad Ghazali, raises the banner of enmity against rationalist Mu’tazilite thought and Iranian culture. Ghazali’s Ihya’ Ulum al-Din becomes the manifesto of this movement, and its adherents begin their assaults on national festivals, rituals, and Iranian epics. 20

Among the peaks of Khorasani literature, the highest epic in the history of literature was composed by Hakim Ferdowsi, in the circle of scholars of his time and supported by numerous prior efforts. This national epic simultaneously contained both the historical spirit and the new ethos of the Iranians, and its composition in the new Persian language not only revived the past but also shaped ‘the future of Iran.’ With the creation of the Shahnameh, not only was the cultural archive of Iran transferred into the new Persian language, but a treasure trove of vocabulary and metaphors, as well as ancient poetic meters (such as the ‘mutaqarib’ meter) and particularly the old Khwarezmian meter 21, were revived and solidified. The work of Hakim Ferdowsi had a profound impact on the historical spirit of the Iranian people, resulting in a ‘new birth’ in the organization of Iranian thought and historical consciousness. His work marked the pinnacle of a cultural reaction to a political defeat.

The Khorasani School is a detailed representation of the cultural spirit of Iran; a treasury that encapsulates the achievements of thousands of years of Iranian culture and thought. In this school, artistic themes, subjects, and more broadly, the idea of Iranian culture, are adorned with a new ethos. All styles and methods of Iranian art in subsequent periods have their roots in the sources of this school.

At the same time, the Khorasani School reaches its conclusion with an era of blending; in its final years, the severe impacts of newly emerged crises have become evident. It is an age of turmoil and decline, with national states in different regions of Iran, such as the Samanids in Khorasan and the Buyids in the center and west, weakened and collapsing due to competition or warfare with newly rising powers. An alliance between the Turks and the Arab Caliphs is taking shape, which will have significant consequences for Iran. An era is ending, another is beginning, and there is an interlude lasting a century until the rise of the Seljuks on the scene.

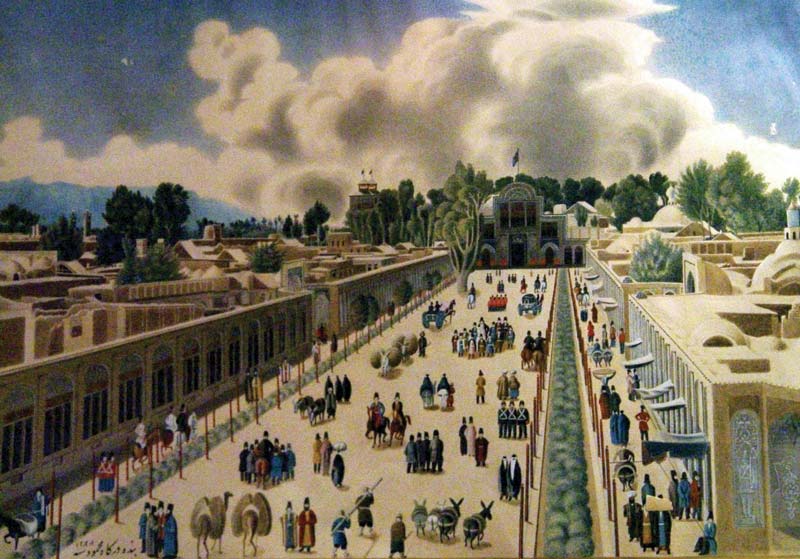

4. Fourth period: ‘State of Culture’; from the mid-12th century AD to the 18th century AD.

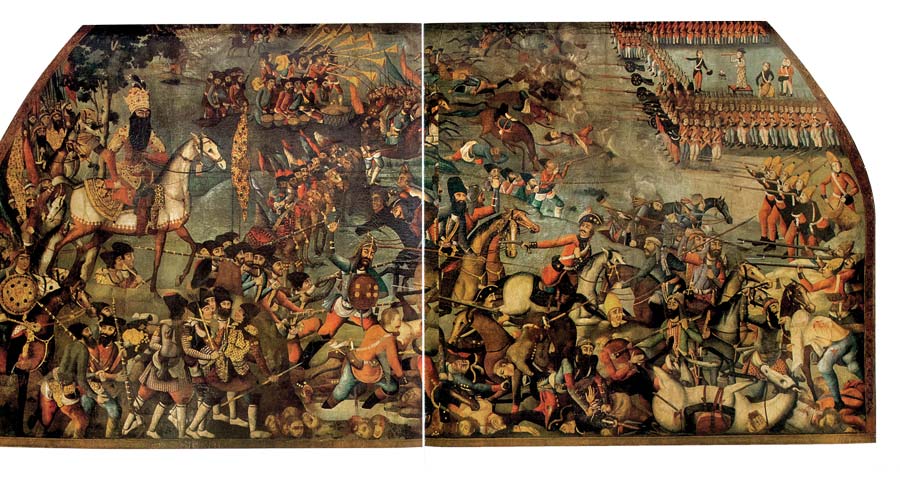

The context of the fourth period in Iran begins with the fall of the national states and, with the successive invasions of the Turks and Mongols from the 7th century AH / 13th century AD, history turns in such a way that a new era can be recognized.

The description of the devastations that marked the beginning of this period is so overwhelming in the accounts of those who witnessed it that ‘there is no order to speak.’ Atta-Malik Juvayni vividly records the realm where ‘the wind of God’s self-sufficiency blows.’ At the same time, the vast and nearly unified territory, which, relying on the power of the Mongols and through the initiative of thoughtful ministers, was freed from the heavy shadow of the Caliphate, also provided an opportunity for unprecedented cultural flourishing and dissemination.

In the political sphere of this period, the experience of establishing states, heavy defeats, and repeated efforts for revival was repeatedly encountered, and it continues to be experienced today. These draining crises and successive collapses led to a general weakening of rationalist thought and a slide into decline.

Here, we mention a few characteristics of this period and leave their detailed exploration for another time:

A major feature of this era can be seen in the investment of resources into the field of culture and art. During this time, it seems that the creative seed of the Iranian core continued to survive solely in its ‘subtle body,’ which is ‘culture and art,’ while the protective shell, crafted with other civilizational components, becomes increasingly fragile, thin, and less durable.

It is possible that the roots of the separation between the destiny of ‘culture’ and the fate of ‘state’ can be traced back to the formative period of Iran, as explained in the discussion of the formative period. Iran emerged as a pre-state nation—or a nation that was born from the shared culture of its people before the establishment of a central government. Thus, it is not surprising that such a nation may have continued its existence independently of its state. Considering this important characteristic may at least provide an answer, from one perspective, to the serious question of how, despite heavy defeats and centuries of lack of a comprehensive national state, Iran has flourished in its art and has not shown signs of decline and collapse in various branches of culture that correspond with the events in the political sphere.

Javad Tabatabai notes in his work on the history of political thought in Iran that the great figures of this culture established the state through poetry, and the Persian language holds a special and unique place in this regard. Therefore, Persian poetry cannot be seen merely as a linguistic domain but also carries the weight of other realms, including political thought. For example, understanding the place of Hafez cannot be done solely through literary rhetorical techniques; he is the ‘tongue of the unseen’ and the language of hidden meanings. The survival of Iran, thanks to such subtlety that can be called ‘the establishment of the state within culture,’ was made possible; meaning that as the field narrowed in other areas, the idea of Iran overflowed into art.

The Khorasani School is the result of cultural continuity despite military disruption and defeat. Thus, referring to its most significant achievements during the period of defeat has provided spiritual support for the continuation of culture. Therefore, it is not surprising that the greatest number of copies of the Shahnameh were produced after the Caucasus wars.

Ferdowsi lived on the border of two eras and witnessed the moment of sliding into a terrifying abyss. Through the voice of the general Rostam Farrokhzad, he predicts a great danger for the future of Iran:

‘These long sufferings will come to ruin, A long decline lies ahead before ascent. In suffering, one will encounter another, Justice and charity will not be considered. They will turn away from their promises and truth, Injustice and deficiency will be honored. The warrior people will become foot soldiers, And those who boast and speak will be mounted. The farmer will become a warrior without skill, Race and art will become less valuable. They will steal from each other, and the curse will be unknown to the creator. The hidden will be worse than the apparent, The hearts of their kings will turn to flint. Fathers will become ill-disposed to their sons, And sons will become adversaries to their fathers. The unskilled will become the ruler’s servant, Race and nobility will not be of use. No one in the world will remain faithful, Souls and tongues will be full of deceit. From Iran, from the Turks, and from the Arabs, A new race will emerge among them. Neither peasant, Turk, nor Arab, Their words will play with deeds. All treasures will be hidden under skirts, They will die, and their efforts will be given to the enemy. The sorrow and distress will be so apparent, That joy will be like the time of Bahram Gur. No festivals, no entertainment, no effort, no pleasure, All that remains will be the strategy of hunting and traps. People will seek harm for their own gain, And religion will be put forth as a pretext. There will be no spring or winter, And no time for joyful wine. As much as this story is told, No one will look towards freedom. They will shed blood for their desires, And the times of greatness will diminish.’

On the other hand, the complexity of the language of someone like Hafez is different from the clarity and straightforwardness of Ferdowsi’s language. While until now the different layers of characteristics interwoven in Iranian culture could be distinguished and even somewhat differentiated in the multilayered existence of an individual, in this stage these characteristics are interwoven to the point of being almost irretrievable: it is difficult to discern whether the world in which Shah Abbas breathes is oriented towards the Zoroastrian Saoshyant or the ancient savior.

Iran, in this period of its historical development, achieves a new form of cultural innovation. As mentioned, during the period of amalgamation, the products of schools and the works of great figures in architecture, music, philosophy, and calligraphy were disseminated within Islamic civilization. However, in this era, Iran’s path diverges from the rest of the Islamic world, and the products of each branch of wisdom and art remain unique to this culture. This phenomenon can also be explained through the crystallization of the spiritual complexity that results from the amalgamation of Iranian, Greek, and ancient characteristics.

For example, in the previous era, great figures like Farabi and Avicenna addressed the Islamic world and defined themselves in relation to it. However, a characteristic of this period is separation; the path that Suhrawardi takes in his Illuminationist philosophy is not easily extended to the Islamic world. He seeks to establish anew the seeds of the Persian school and Khusrawani philosophy with a fresh awareness. Suhrawardi criticizes Avicenna for not having a good understanding of Iranian angelology. Among the greatest later philosophers who follow a similar path, but from a different perspective, is Mulla Sadra. He views the relationship between existence and essence from another angle and steps into a realm that is not only not common in the Islamic world but may even be incomprehensible and dangerous to some. The emergence of new ideas that result from a hybrid nature has influenced the resistance faced by some of these great figures, including Suhrawardi and Mulla Sadra. 22

In music, a new system of seventeen notes is established, which differs from the previous era’s system that was shared with the Islamic world. 23 The expansion of Shia principles is also understandable within this context.

In architecture, new motifs are invented, such as the bridges built in the style of Isfahan, which clearly continue the architectural tradition of the Khorasani school while achieving a new kind of poetic miracle in working with the material of the earth. The use of reflective effects, reflections, and motifs that have dual functions depending on the light remains predominantly specific to Iranian culture and does not spread throughout the rest of Islamic civilization.

There are many other examples in various fields. For instance, while the Thuluth script spread throughout the Islamic world, achieving perfection in Ottoman calligraphy, the proportions of the Nasta’liq script remained uniquely confined to Iran.

At the beginning of the period we call the ‘Dawn of Culture,’ Turkish rulers, emerging from a different cultural background, come to dominate parts of Iran and quickly become influential supporters of Iranian culture. Although Sultan Mahmud, driven by the desire to seize spoils, campaigns in India, the movement of numerous poets, scholars, and artists in his court extends the reach of the Iranian language and culture to the Indian subcontinent. The Seljuks also rapidly adopted Iranian culture, and the legacy of Jundi-Shapur continued in the Nizamiyahs established by Khwāja Nizam al-Mulk, the wise minister of the Seljuk ruler Malik Shah.

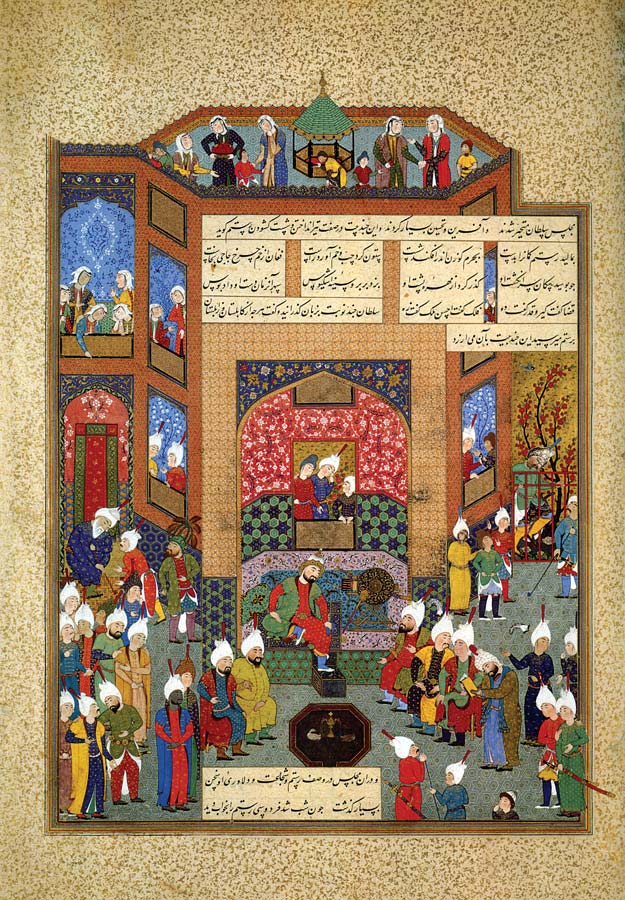

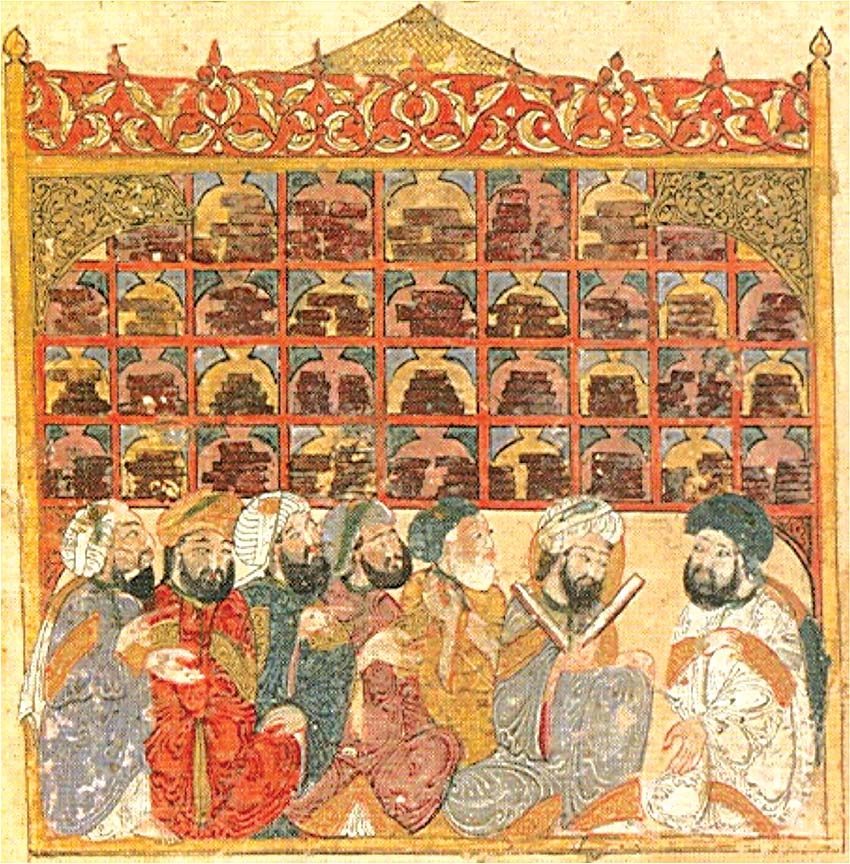

Along with the Mongol invasions, Nestorian and Manichaean Christians also return to Iran. Through this, Manichaean painters, who are traditional bearers of a developed tradition of painting and book illustration, come back to Iran, bringing with them a new phase in miniature painting and book decoration.

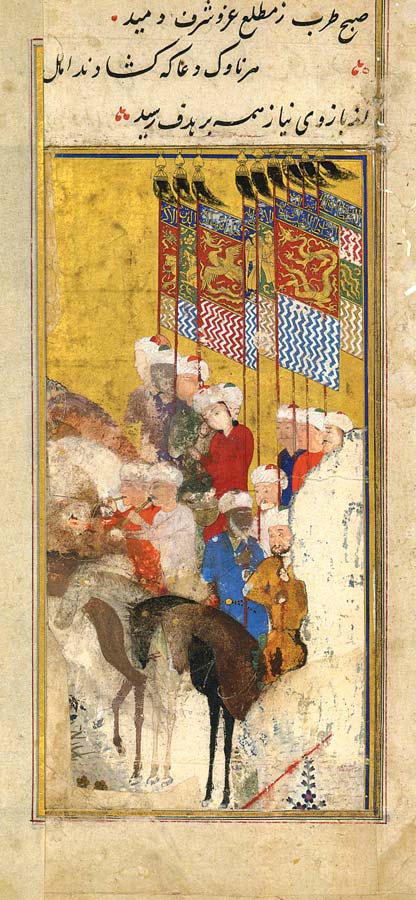

This period can also be recognized by the rise of a lyrical spirit and the growth of interest in Sufism and mysticism in various schools. The Safavid political structure itself was based on the tradition of Sufi circles, indicating the increasing influence and widespread nature of this current within the Iranian spirit. It seems that, in the absence of a central state, part of its role was transferred to the monasteries, establishing a branch of power in this domain. It is no coincidence that the Sufi leaders were called ‘Shah’ and communities formed as disciples and followers pledged allegiance to them. On the other hand, within mysticism, a perspective emerged that focused on the ‘human condition’ in a broader sense and cast its gaze beyond the ongoing conflicts.

Thus, although the fourth period begins with widespread devastation, if we trace the cultural responses of the Iranians through the downturns of this long era, we see, contrary to expectations, how areas of art and culture were repeatedly opened up even in times of intellectual rigidity and decline. Therefore, it is not surprising that, alongside the hardships and decline in other areas, the history of art in this period is recognized for the flourishing of multiple and diverse styles.

Following the break from the Khorasani School, the continuation of the arts occurs in a series of styles, none of which, in terms of their scope, establish a new school. The social history of this period can be briefly marked by significant events relevant to the study of artistic styles:

• From the destructive invasions, the end of the national states, to the arrival of Genghis Khan and the widespread Mongol invasions.

• The invasions of Hulagu Khan and the attacks by Timur and the Uzbeks.

• From the Battle of Chaldiran to the fall of Isfahan.

A list of styles that emerged amidst the turbulence of this period includes:

• At the end of the Khorasani School period, the ‘Razi Style’ appears. 24

• After the Mongol invasions, we witness the emergence of the “Azerbaijani Style” and the “Shirazi Style.”

• Concurrent with the devastations caused by Timur and the Uzbeks, the “Herati Style” comes into prominence.

• With the victory of the Safavids and the establishment of the national state, the achievements of the Azerbaijani and Herati styles are consolidated into the “Qazvini Style,” and subsequently, during the reign of Shah Abbas I, the “Isfahani Style” reaches its peak.