An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

The rise of the Achaemenid Empire, marking the beginning of a new chapter in civic experience and the establishment of a political-historical system, is a subject that requires further research in various fields. The emergence of such a novel structure in power resulted from a vast and multifaceted collection that we call the “Iranshahr Cosmology.” This cosmology arose in a region with a history of sedentism as old as human civilization itself. The heritage of several millennia of urban systems experience was integrated into this cosmology, providing it with the capabilities to form a global structure and enabling its transformation from the organization of a country into a global empire.

Considering the numerous developments that took place between the era of painted pottery and the age of the first formation of Iranian culture, the establishment of the “Iranshahr Cosmology” and its manifestation in the “Persian School” can be regarded as the “culmination of the first birth” of this culture. Alternatively, from another perspective, taking into account the millennium of conflict and war that transformed the older methods based on peaceful and warless living, the Persian School can be seen as the product of the “rebirth” or the first Renaissance of this culture.

As mentioned in the previous discourse regarding general definitions, in some cultural centers, cosmologies have emerged as foundational historical ideas, each standing on the basis of its own cultural nature. Generally, some of the most significant manifestations of a cosmology include advancements in refining language and script, the introduction of religion and rituals, the systematic formation of sciences (such as astronomy, mathematics, medicine, geography, etc.), and the development and expansion of engineering techniques. In this lecture, we will explore certain aspects of the Iranshahr Cosmology in this context. Attention to the various facets of this cosmology is particularly important because it provided the foundation for the schools that emerged throughout the long history of this land, all of which have their roots in the period of their initial formation.

Let’s begin by examining a few words and their usage: Addressing the concept of sovereignty in its various dimensions, without generalizing the rules of the modern world to the ancient lifeworld, compels us to consider the roots of this concept in its own context: The word “Raynak” in Old Persian (the language of the Achaemenids), and also in Middle Persian (Pahlavi), conveys a different concept from that of the state. In previous discourses, we referred to a kind of awareness that draws upon the concept of “Bon-dehesh” to explain the creation of the world, as well as the difference between the meaning of “birth” (zayesh) and the concept of “nation.”

Thus, it is crucial to pay attention to the intrinsic differences between certain terms that are often considered equivalents in translation, such as “Shahanshah” and “Emperor,” or the common mistranslations of the Greek word “polis”—which is governed by “kratein and archin”—to the term “city” in Iranian thought.

The words “shahr” (city) and “Shahrevar” (an Amesha Spenta) share a root with the name of one of the seven Amesha Spentas, “Khshathra Vairya,” meaning “Desirable Dominion.” This concept, which took root in Old Persian, has been borrowed by other languages in its outward form; “Khshathra” (Khosrow), which with the prefix “Kai” became “Kai Khosrow” (Kavi Khshathra), entered other languages, giving rise to terms like “Kaiser,” “Caesar,” “Czar,” and “Tsar.”

A summary of the political formation of the Achaemenids, based on historical documents and research up to today, is as follows:

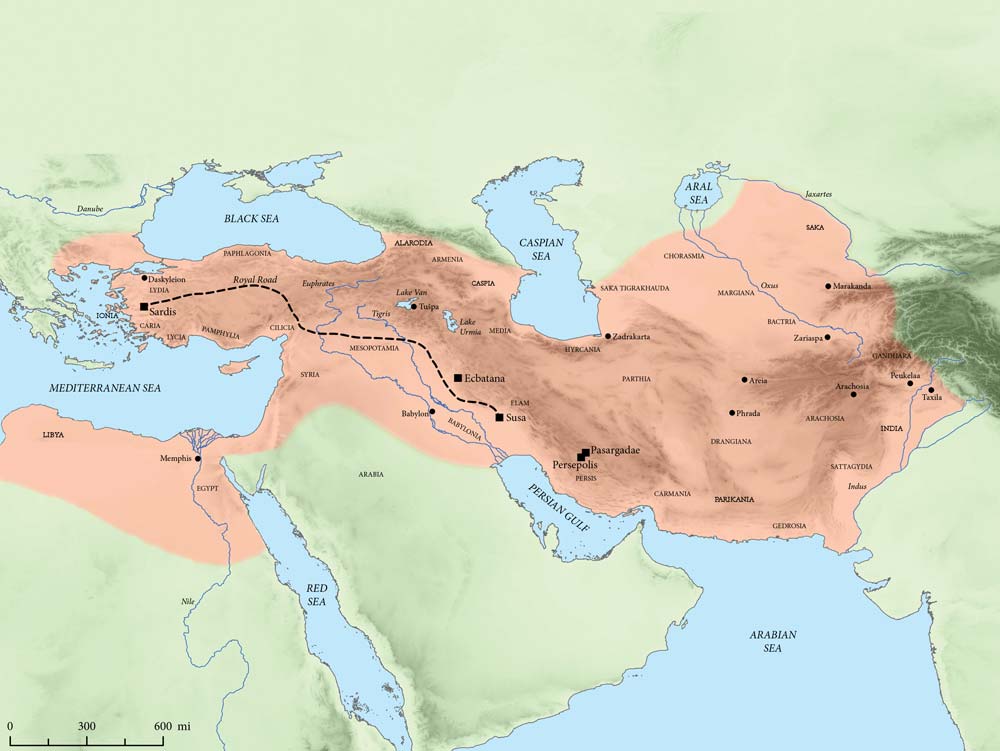

The Assyrian annals of 834 BCE first mention the realm of Parsua in the south and southwest of Lake Urmia. Then, around 700 BCE, this kingdom settled in the region of Parsumash, on the slopes of the Bakhtiari Mountains, southeast of Elam’s territory. In the tense environment resulting from the conflict between Elam and Assyria, this small kingdom, founded by Achaemenes, expanded further. Achaemenes’ son, Chishpish (675-640 BCE), declared himself king of the city of Anshan (in the Masjed Soleyman region). After Chishpish’s death, the realm was divided between his two sons: Ariaramnes, king of Pars, and Cyrus, king of Parsumash. At this time, Media, under the rule of Cyaxares, was at the height of its power. Cambyses I (600-559 BCE), son of Cyrus I, unified the divided territories of Pars and moved the capital from Masjed Soleyman to Pasargadae. The victory of Cyrus II (559-530 BCE), known in history as Cyrus the Great, over Astyages, king of Media, united Pars with Media. Cyrus the Great and Darius I (521-486 BCE) established the first and most extensive empire in history.

Moreover, whether in the modern era concerning newly established countries or in ancient countries, we often find a shadow of the foundational awareness upon which the establishment of the country was based reflected in its naming. The name “Iran” is not indicative of a specific ethnic group (like Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Rwanda, Zaire, Congo, and many others), nor is it a name derived from a smaller province generalized to cover the entire land (such as China, derived from the province of Tian, or the name of the Emperor Tan from that region), nor is it a metaphorical name describing geographical characteristics (such as the Netherlands, meaning “low land,” Iceland, meaning “ice land,” Vietnam, which in ancient Chinese means “southern land,” or South Africa), nor is it a specific ethnic name (like England, attributed to the Anglo-Saxons, or Britain referring to the Britons, or Germany named after the Germans), nor is it the name of an explorer or conquering tribe (such as America, named after Amerigo Vespucci, France derived from the name of the conquering Franks, or Saudi Arabia named after the Saud family), nor is it a creation for political exploitation (like Turkey, which disregards the memory of ancient Anatolian peoples such as Armenians, Kurds, and Greeks).

The name “Iran” is a phonetic and linguistic transformation of the Avestan term “Airya Vaeja,” which appears in Middle Persian as “Iranoich,” and later evolved into “Aran Shahr” or “Iranshahr” 2 in New Persian, eventually becoming “Iran.” The first part, “Airya,” derives from the root “Er” meaning “free,” while the second part, “Vaeja,” means “place” or “location,” which is reflected in Middle Persian as “Vaech.” Thus, “Iran” translates to “Land of the Free.” 3

The name “Iran” appears frequently in ancient histories and various geographic, historical, and literary texts. Beyond ancient Pahlavi texts, in New Persian, the term “Iran” is mentioned over five hundred times in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, and more than forty times in the works of Nizami Ganjavi, as well as in other literary works.

All the world is the body, and Iran is the soul;

The speaker is not ashamed of this comparison.

For Iran is the heart of the earth;

Indeed, the heart is better than the body.

(Nizami Ganjavi, Haft Paykar, The Prayer of Krep Arslan)

It is also important to give further consideration to the terms “Pars,” “Parsa,” and “Persian.” In ancient geography, as we know, “Parsa” was the name of a prosperous city. However, it is not certain whether the term “Persian” was used solely to refer to a specific ethnic group, meaning individuals with blood relations. Particularly, in some contexts, it seems that the term was used as an adjective to describe the characteristics or qualities of the people.

In Greek and Roman sources, which have been extensively expanded upon by Western researchers, the names “Persia” and “Parsa” appear frequently. Among Greek scholars, for example, in the writings of Socrates, the terms “Persian” and “Parsi” are used as adjectives to describe well-educated individuals. This usage of the term was also adopted by the Romans. For instance, in Roman Mithraic rites, one of the hierarchical ranks (a position before the father) was called “Perses”; and some Roman emperors and senators used the title “Perses” 4 to signify their character and distinction.

The term “Perse” was also used in Latin to refer to a person’s inner character. By extension, it was applied to the masks and disguises used by actors to assume their theatrical roles, a meaning that persists today. The connotation of this term, which denotes personal distinction and education, has been carried over into the Persian word “Parsa” in modern Persian.

With the background we have previously discussed—that is, several millennia of accumulated experiences of settled life in the midst of the golden rectangle, where it seems that at the dawn of history, ideas based on the value of land cultivation and domesticating nature emerged, leading to a new worldview that transformed human living conditions; at the center of the convergence of interactions among cities that were shaped around this initial idea, both near and far, and in a specific climate with unique challenges that gradually became more difficult, linking the continuity of life to long-term strategies; and at the same time benefiting from a unique position of experiencing a long period with minimal conflict, allowing for the sharing of achievements among neighboring cities—the conditions for establishing systems of power were created, culminating in the Achaemenid Empire.

In the latter half of the middle millennium, during which wars and conflicts resumed, numerous technical advancements occurred in the civilizations of the Iranian Plateau, including the ability to extract iron. The production of tempered steel was among the advancements that led to technical superiority in manufacturing various tools, including weapons (while the Pharaohs of Egypt continued to use bronze weapons). Additionally, the invention of the wheel and the chariot facilitated rapid mobility and transportation.

A significant volume of the outstanding artifacts from the Achaemenid period consists of vessels and related tools. A large collection of plates, spoons, strainers, mortars, jugs, and very fine rhytons has survived from this era. This collection is valuable for research in terms of construction techniques, uses, and design intricacies; and perhaps most notably, the design forms and motifs of these vessels carry the most important meanings of awareness from this period. These vessels reflect the continuity of dining rituals that dated back to the era of painted pottery in the Plateau, which we discussed in previous lectures. This tradition was later perfected in the plates of the Sassanian period and continued in the design of motifs and patterns on pottery after the Islamic period.

The outcome of these transformations and the accumulation of experiences was the emergence of a political power and will that, over more than two centuries, encompassed a vast territory, nearly two-thirds or seventy percent, of the cities of the contemporary world. This power implemented a new form of governance that employed various tools, from warfare and conquest to executing monumental infrastructure projects, developing bureaucratic systems for administration, and promoting connections that ensured the collective interests of diverse groups. Under this new system, cultures, races, and languages, despite their diversity, were unified within a broader framework.

This comprehensive and entirely new system posed new questions and issues, and generated specific answers for them. The new social order and the development of its hierarchy also reflected a novel explanation of the creation mechanism, transferring the celestial and terrestrial hierarchy to society. In this new order, it seemed as though the “spirit” was placed in a higher realm beyond the natural state; a question arose that could only be answered by the persistence of the spirit in achieving a hierarchy of awareness.

These transformations, continuing from the earlier shared agricultural period, had a profound impact on the contemporary world and connected the initial idea of settled life to the establishment of a conceptual system in the history of thought.

Civil Life in the Iranian Worldview

With the break from the confines of the natural state and the establishment of a civic order, the freedom of historical human spirit is realized. This new civic life manifested itself in the characteristics of the Iranian city, which differed from past experiences and other centers. For the first time in the history of urban planning, centers emerged that, in their foundational meaning, offered a model of a capital and political center. The city was not merely a fortress, a temple of the king-priest, or a city-state in the Athenian sense; rather, it was a complex amalgamation of a designed and interconnected set of structures with various functions, such as residential areas, public spaces, infrastructure facilities, and administrative buildings, in relation to other cities rather than in conflict with them.

Historians also tell us that the Achaemenid Empire did not limit itself to a single central city; Cyrus the Great’s governmental center was initially in Susa before Pasargadae, and later Ecbatana and Babylon were added. Looking at the history of Iran, we know that this multiplicity of power centers existed in most Iranian national states, including the Parthian and Sassanian periods, as well as under the Buyids and the Samanids. For instance, the Parthian capital was located in three cities: Ashkhabad, Damghan (known as the “City of a Hundred Gates”), and Ctesiphon. The necessity for multiple centers was related to the vast geographic extent of the land, which, alongside other factors, contributed to a unique political structure for managing the territory, organized into the system of seven regional governors. 5

Thus, it is natural that among these centers, a network formed. The primary characteristic of cities in this newly defined system of continuity was their relationship with other cities; that is, the awareness that achieving stable continuity depended on the connection between centers. Accordingly, a notable feature of Iranian cities was the extensive chain-like roads that connected the centers to each other. While the old natural paths met the basic needs of the inhabitants for access to neighboring areas, these historical routes, with a broader concept now known as “strategic geography,” were constructed with engineering structures, forming a network of transportation, communication, information dissemination, and support with the potential for global expansion.

According to archaeological data, these roads also reflect advancements in engineering knowledge. The paved, cart-accessible roads show attention to the use of materials, route determination, and finding the safest passages free from natural hazards. One notable example is the 3,000 kilometers of paved road stretching from Susa to Sardis. The tradition of road construction continued throughout all periods of prosperity, with efforts focused on repairing and expanding the roads. By the Parthian period, over 5,000 kilometers of roads had been constructed, and by the end of the Sassanian era, approximately 7,000 kilometers of roads had been built in Iran. 6

Among the notable engineering structures were the numerous bridges, many of which are known by the name “Pol-e Dokhtar” (Daughter’s Bridge), built at elevations above the highest flood levels. Additionally, the construction of fortresses for control and surveillance to ensure road security, often referred to as “Qaleh Dokhtar” (Daughter’s Fortress) in the culture of the regions, was prominent. The construction of caravanserais (known as “Rabat”) to provide comfort, security, and meet the needs of travelers along long routes, the establishment of a postal and courier network for the transfer of correspondence, and the invention of an extensive fire signaling network across the land for urgent message transmission were significant innovations of this period. The remnants of towers and fire temples used for this communication system still stand on high points along the routes and atop hills in many parts of the region. 7

Under the Iranian worldview, cities and major centers were connected by highways; the network of land and sea routes was developed beyond local access, shaping what we now refer to as “strategic geography.” This included the design of transportation systems, communication, information dissemination, and support networks with the potential for global expansion. The focus on road construction became a tradition that continued for millennia; research shows that by the end of the Sassanian period, approximately 7,000 kilometers of roads had been built in Iran. One of the important projects of the Safavid period to revive Iran as a unified country was the reconstruction of roads and the construction of over nine hundred caravanserais and caravanserais. This was made possible by the historical experience and the transfer of knowledge accumulated from the millennium preceding this development, which was itself based on the accumulation of experiences from the formative period of this culture.

Undoubtedly, the requirements of such a network developed across various dimensions; from the breeding of useful pack animals for transportation, to advancements in related technologies such as the wheel and chariot, to the production of appropriate clothing, and the organization of administrative correspondence, including the widespread use of seals that ensured the authenticity of documents and messages.

There is also considerable evidence showing the extent to which efforts were made to expand maritime routes, and to excavate and construct massive waterways and canals, such as the Suez Canal, and to bridge rivers like the Euphrates and the Dardanelles. In key locations along these routes, including the port of Marseille in the Mediterranean, Cyprus, the Aegean, Kish, and the Red Sea, large stone structures were built. Evidence also exists of the creation of the first lighthouses to ensure safe navigation within the maritime network. 8

Along the extensive routes of these roads, inscriptions, documents, and records of their establishment have survived from the ravages of time and natural disasters. These texts often include recommendations for virtuous deeds or information intended for recording in history and passing on to future generations. Examples include:

• The inscriptions of Xerxes around Lake Van.

• The inscriptions of Darius at Suez and at Bisitun, alongside one of the major highways known as the Royal Road.

• The inscriptions of Darius and Xerxes in Hamadan, one of the key bases of the Royal Road.

• The inscriptions of Sindh and their influences in the Indian subcontinent, such as the Ashoka edicts.

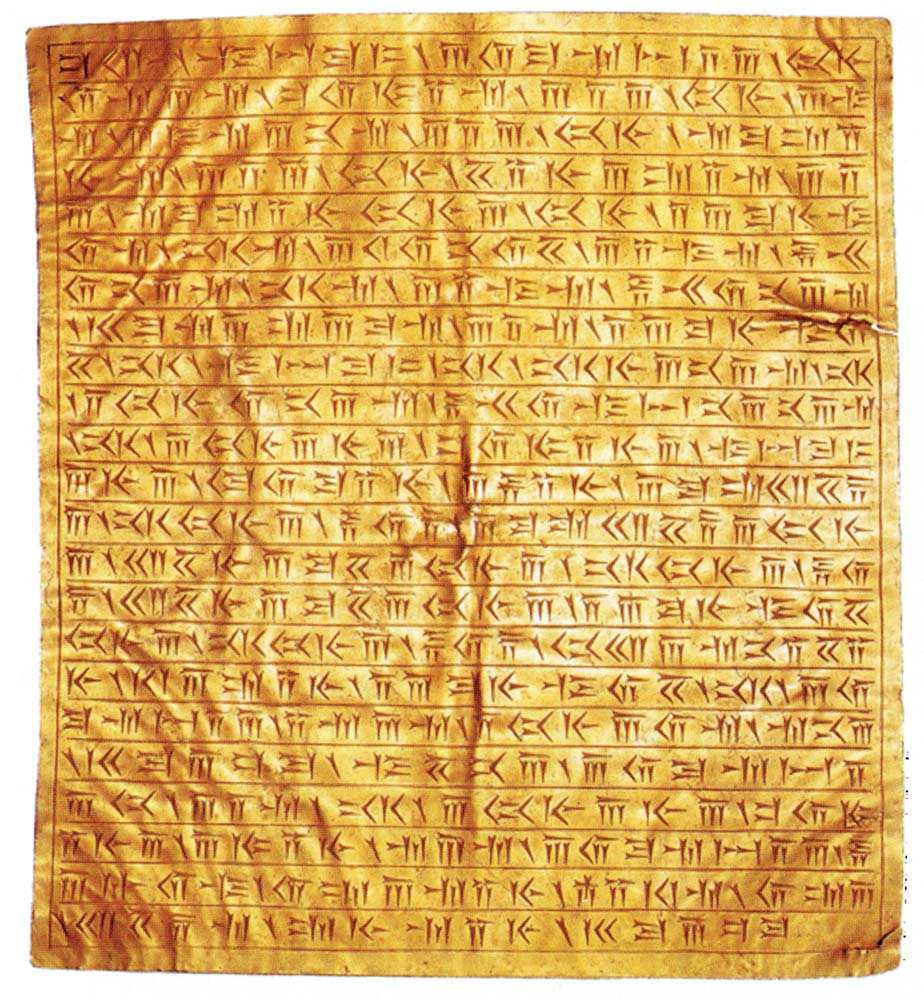

• The satrapal documents found in various locations, often in the form of cubic stones.

These inscriptions reflect the enduring legacy and administrative organization of the Persian Empire.

A significant feature of these road inscriptions, or stone carvings and other documents within this system, is the use of three types of scripts and languages (Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian). Although the scripts and languages evolved over time, this multilingual characteristic continued as a tradition throughout the history of Iranian civilization.

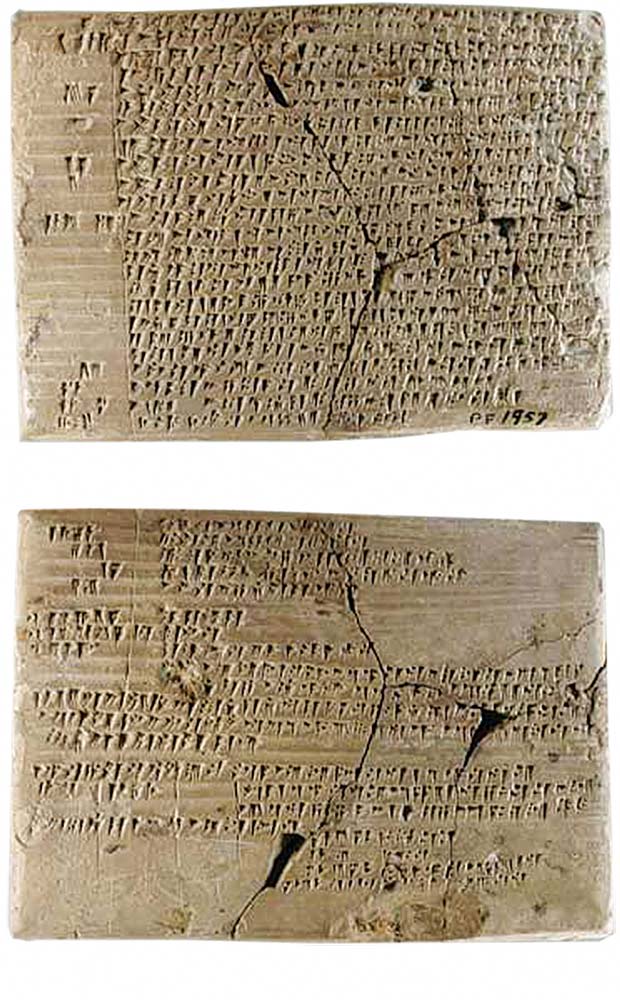

A very large number of clay tablets have been discovered from Persepolis, containing a wide range of administrative documents. Similar tablets have also been found from excavations in Shush, Kandahar, Armenia, Babylon, and Hamadan. It is certain that many documents were also inscribed on materials with shorter lifespans, with traces of their decayed fibers remaining on the clay seals that protected them. This volume of documents and correspondence required a special organization for documentation and exchanges.

Among the tablets from Persepolis, there is a document in which an official states that their previous seal is now invalid and that the new seal, a sample of which is provided, is the valid one. The text of this decree is itself sealed with the seal of the chief administrative authority of Darius.

Source: Mahdavi, M.

One of the main scripts used in these inscriptions and other documents of the Persian administrative school, as mentioned, is Old Persian cuneiform. Most scholars attribute this script to the time of Darius. Compared to other scripts of its time, Old Persian cuneiform was designed with fewer symbols, a simpler logic, and sufficient precision suitable for information dissemination and record-keeping. (The topic of script and language will be revisited later in this discussion.)

The design of roads and large-scale experiences with distant climates and lands had a reciprocal relationship with geographic knowledge. A people’s awareness of their habitation within nature and even their understanding of the relationships between their terrestrial habitat and the cosmic world dates back to very ancient times. Geography, which emerged from these early insights, expanded the initial view of the ecosystem’s relationship with the world to a new scale. Under the Iranian system, based on land surveying, exploration of territories, and investigation of climates, a new chapter in human awareness of both human and natural geography emerged. 9

In this new framework, attention was paid to the differences among climates, peoples, cultures, and customs. Under this system, every climate and every group of peoples could be named and recognized. Thus, for the first time, all the lands and peoples of the era were categorized into large groups. These classifications were likely beyond the scope of awareness of these peoples who lived under tribal systems. For example, one of these cases is the designation given to the lands and peoples of Greece and Ionia within the Iranian system. 10

One of the notable achievements of geographic knowledge within this framework is the determination of the “Noon” (Nimroz) meridian, which dates back several centuries before the common era. The characteristic of this geographical region is that, at the moment when the sun reaches its zenith in this area, the entire ancient world—encompassing Asia, Europe, and Africa—is experiencing daylight. This region is unique in this regard. 11

It is clear that awareness of this feature required geographical information, mathematical calculations, and astronomical knowledge. Ancient astronomers calculated the world’s celestial positions, one of their most significant tasks, with respect to this meridian. The necessary resources for such surveying projects and studies on the longitudinal and latitudinal dimensions of the known world demanded extensive records, measurements, and coordination. During this period, a title existed for overseeing such projects, which included astronomers, geographers, and calendar regulators, and this title was “Faratdar.”

Parashandata, son of Artadata.

The subject recorded on many clay tablets pertains to the allocation of wages for individuals from various ethnicities and genders. These records typically detail the number of subordinates under a craftsman and their respective wages.

In ancient Iranian geography, the naming of cities and regions often reflected geographical features, climatic conditions, and the social role of each city. Given the vastness of the land and the historical administrative divisions, a variety of terms were used to refer to different areas. Thus, city names commonly incorporated prefixes and suffixes, each of which is a subject of research. For example, the suffix “kand” can be found in names like Samarkand, Zafarqand, Mehrkand, or as a prefix in names such as Gundeshapur (also known as Jundishapur). Similarly, “gard” appears in names like Susangerd, Boroujerd, and others. Another example is the prefix “bakh”/”baj”/”bek”/”bag”/”bai”/”bi” seen in names such as Baghdad, Bagpur, Baku (Bai-Kuh), Azerbaijan (Atur+bi+gan/jan), Bisotun (Bi+stun), Bishapur (Bi+shapur), Bajestan (Bi+jastan), and Bijar (Bi+jar). 12 There were also various terms for local administrators and rulers.

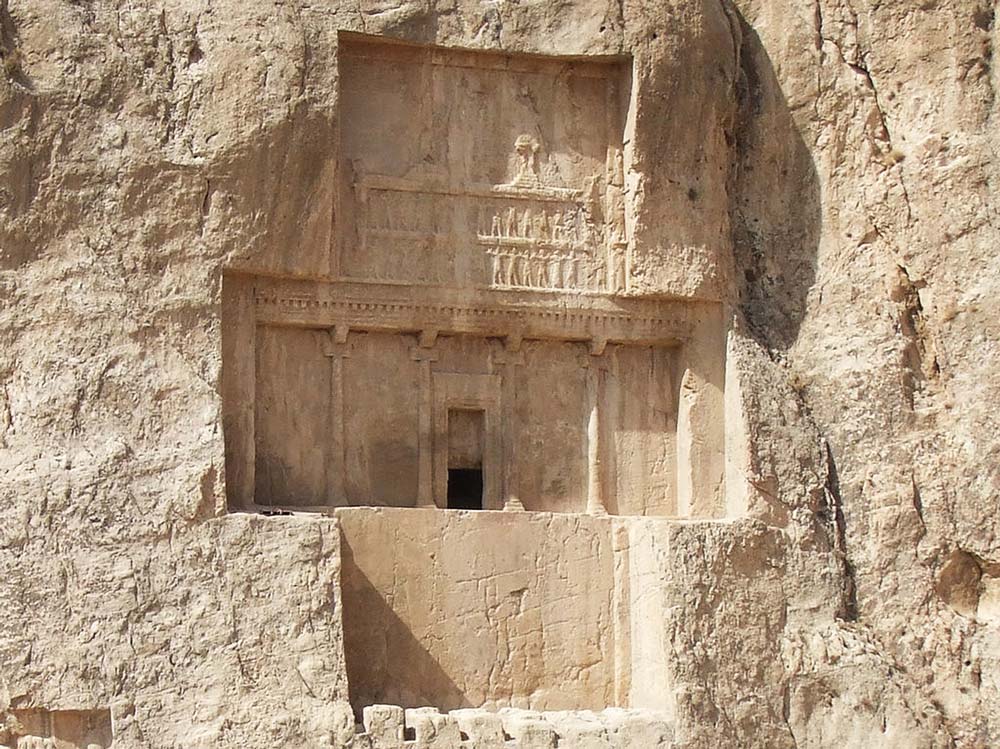

Additionally, the civic structure we are discussing relied on administrative or bureaucratic organizations. Important texts, calculations, and records of major state projects were documented and archived for extended periods (some clay tablets found at Persepolis date back to the reign of Darius and were preserved until the fall of this dynasty). Libraries or “dijnepeshte” were established to store and record knowledge and documents. Among them was a building in Pasargadae, with a similar structure also found at Naqsh-e Rustam. Professor Henning, using inscriptions commissioned by Kartir on the walls, believes that these buildings served as archives for religious documents and the preservation of original texts, including the Avesta.

Additionally, mechanisms were developed to monitor public health, to the extent that health-related issues were recorded in bureaucratic archives; among them were sanitary regulations such as the “Law of Nishveh” (or “Nine Nights”) for the quarantine of travelers. The practical and theoretical result of accumulated experiences in this area was the gradual development of a system for understanding bodily functions and pharmacology under this framework. 13

Among other achievements was the standardization of measurement units and the system of weighing throughout the empire; standardized weights with inscriptions from the king were sent to distant and nearby locations. Work was done on calendars and the precision of timekeeping, and mints in various parts of the empire struck gold and silver coins using standardized measures. 14

The Mil-e Zhandaha (or the Dragon Tower) in Noorabad, Fars, is one of the remaining towers from the Parthian period, and its design is very similar to two examples of buildings from the Achaemenid era at Pasargadae and Naqsh-e Rostam. This structure is situated outside the city, and remains of a fire temple can be found at its top. Both in the naming of the tower and in the name of the nearby settlement, there is a reflection of a distant memory of lighting fires at its height.

‘’Documents, including those in Greek sources, indicate that the Iranians had developed a system for transmitting important news through fire towers across their empire, which astonished observers. This method, based on the infrastructure development of the period, has been less studied.

Across the vast territories of this empire, there is a significant number of stone towers and pillars. In many cases, the remains of fire altars at the top of the towers and evidence of the dwellings of guards around them are still identifiable. Without a comprehensive view of this diverse and scattered collection, each of these structures is often known as a fire temple, tomb, altar, military tower, etc., and there are imprecise local beliefs about each.

Sources suggest that these towers extended from two origins, one at Susa and the other at Ecbatana, with regular intervals across natural hills and artificial embankments throughout the empire. They continued across mountains and foothills, through valleys and cities, and possibly even in locations far from settlements, with distances such that each station was visible from the next.

This system continued into later periods, being reorganized whenever central power was restored, and was even used to some extent during the Abbasid Caliphate in specific routes. Today, the term “minaret,” which means “place of light,” preserves the original function of these tall fire towers.’’

— Mahdi Mohseni Rad

The drachma was a commonly used currency across a vast area, with its circulation extending beyond the boundaries of the empire. It should be noted that the expansion and influence of coins, seals, and symbols from this system globally were primarily backed by the credibility of the message they conveyed. For instance, the drachma of Darius the Great was used for trade even up to the northern borders of Europe (as evidenced by the discovery of two casks containing Darius’s drachmas in a farm in Gothenburg, Sweden, about 20 years ago). This not only reflects the economic power of the Achaemenid system but also indicates the acceptance and reach of an idea that had become universally recognized. This attests to the development of a power institution whose impact went beyond mere trade of goods.

As the expanse of the territory grew, beyond the oversight and standardization of measurements, the need for numerical computation arose, leading to the flourishing of numerical calculations. Additionally, advancements in surveying, engineering, and astronomy contributed to the growth of other branches of mathematics, including trigonometry. The Iranians adopted and expanded some of the computational methods invented by the Sumerians. One of the greatest achievements in mathematics is the development of the decimal system, which required the concept of zero. The word “zero” comes from the Avestan term “zephar,” meaning circle, which was one of the Avestan punctuation marks, sometimes written as a circle and sometimes as a dot. This term, along with the knowledge of numerical calculations, traveled to Europe and became the root of synonymous words in European languages.

Another leap in mathematics was the emergence of trigonometry, which from beginning to end is a significant legacy of the Iranians. The construction of qanats and the development of a qanat-based civilization in this land required a deep understanding of trigonometry. This advancement allowed for the precise calculation of the gradient of the land, including the depth of wells and the distance from the well’s source to its outlet.

The military, in a new sense, emerged as an organized entity with standardized laws, garrisons, fortresses, and military installations. Remnants of this military organization can be found throughout the vast Achaemenid Empire. Special attention was also given to safeguarding the borders against invasions; among the remains are traces of several thousand kilometers of defensive walls constructed in areas such as the Zagros passes, the Merv-Gorgan plain, and other regions, some of which were later expanded.

Trigonometry is one of the legacies of the Iranians. The fundamental problem is as follows: if a stick is placed vertically on the ground, it forms a triangle with the sun’s rays, the stick, and its shadow. By knowing the angle between the shadow and the sun’s rays, the length of the stick can be measured.

Similarly, in digging a qanat, given the slope of the land and the distance from the outlet to the well’s mouth, the depth of each well can be calculated.

Many fundamental terms in astronomy and trigonometry in European languages are not derived from Latin roots, as is customary, but are second-hand translations of terms established in Persian. For example: Zenith, Nadir, Hora, Tropical, Sidereal, Anomalistic, Sinus, Cosinus, Tangent.

“Sinus” is a mistranslation of the Arabic “jib,” which in this context was not used in its literal meaning (valley) but was an Arabized form of “cheb” or “chub,” referring to the vertical side of a triangle in trigonometry. “Secant” is a translation of the Arabic “qati'” (sword), which is an inaccurate translation of the Persian “tiq,” meaning the sun’s ray. The third side of the triangle, which is “shadow,” was translated into Arabic as “zill,” but Latin translators used “tangent,” derived from the verb “to touch.”

Weights from various centers, both distant and near, within the Achaemenid Empire have been discovered, with most of them inscribed with the king’s name and the weight standard. Some weights are in simpler forms, while others are quite elaborate. The use of weights has a very long history in the cities of Mesopotamia and the Iranian plateau. However, in this case, it appears that the primary focus was on ensuring uniformity and standardization by sending standard samples for measurement to far-flung regions.

Similarly, from around this period, underground cities of sometimes very large sizes were constructed or expanded based on what already existed in many areas of the Iranian plateau. These underground structures likely played a role in ensuring the security of citizens among their various applications. 16

Addressing security was not solely about defending against invasions; rather, the organization of Iranian cities was based on the principle of reducing dependence on natural resources and ensuring a more sustainable and self-sufficient way of life. Among the most important measures in this regard were the establishment of water transfer, storage, and control facilities. Depending on the climate, this included land drainage, canal construction, qanat digging, and the building of numerous water reservoirs. A notable achievement in this area was the creation of a unique system for obtaining and transferring water, which led to the development of the “Qanat Civilization.” All these water infrastructure innovations were expanded globally with the growth of the empire; irrigation projects were carried out in regions such as Mesopotamia, the Nile, and the Vararud, and the techniques of qanat construction were transferred to the farthest regions. 17

From the aspects outlined, many other key concepts emerge that were either developed during this period or were newly experienced in the context of settled societies. One of these foundational elements is the emphasis of the administrative system on public welfare services. This includes the construction and maintenance of caravanserais (road stations), watchtowers, bridges, baths, water reservoirs, canals for supplying water to settlements or for urban wastewater disposal, and the design of public gardens.

Additionally, as documents indicate, the presence of a tolerant attitude towards the diverse beliefs of people, the observance of customary rights, and the enforcement of laws regarding workers and officials were crucial factors in gaining mutual trust. These aspects formed the backbone of stability and continuity.

This public sphere, through the establishment of annual festivals and ceremonies, involving all ethnicities, races, and nationalities, strengthened the social spirit. By fostering a shared understanding of the workings of the universe, it provided meaningful unity within this diverse whole.

There is a wealth of historical evidence regarding various religions and ritual systems that have their origins in Iranian culture. These range from worship and reverence of the sky, earth, and everything in between (as seen in hymns in the Yasna that praise the sun, light, sky, and water), to Zoroastrianism, which focuses on the veneration of wisdom, intelligence, and good deeds. Other religions, such as the cult of Mithras, Christianity, and Manichaeism, also have roots in this cultural sphere.

One of the surviving examples of hydraulic structures from this period is the Bahman Dam on the Qara-Aghaj River. This dam redirects the river’s course and irrigates the fields of the Kovar Plain. The dam, which still stands after subsequent repairs, exemplifies the engineering techniques, material science, and geographical considerations of the era.

Religion, derived from the root dæna in Avestan and Old Persian, means the view within or the place of inner voice, carrying the meaning of conscience. Thus, the meaning of this term in Iranian thought differs from the concept of prophecy in ancient traditions and Abrahamic religions. In this system, religion is primarily a realm that opens the domain of conscience within the human world and deals with the sphere of beliefs and the awareness of the spirit of the people.

In the Achaemenid period, there is little evidence of an official religion, as the surviving documents indicate that various rituals were consolidated under a general idea. Greek historians report that during this time, the Iranians did not construct dedicated temples or shrines in the conventional sense. In the ancient civilizations of this region, such as those found in Aratta (Jiroft), Sialk (Kashan), or Chogha Zanbil, people would gather around a sacred structure like a ziggurat, similar to the Mesopotamian tradition.

In the subsequent transformation, the settlement patterns of the Iranian people changed, and cities, urban governance, and administration were restructured based on a new understanding. This shift meant that the role of sacredness, previously associated with gathering around a high priest or a sacred site—which was a continuation of the early gatherings around a priest’s tent—was abandoned. This represents one of the key differences between the concept of “city” in Iranian thought and the “polis” in Greek thought—specifically Athenian thought—where the community centered around an “Acropolis,” a sacred place on a hill.

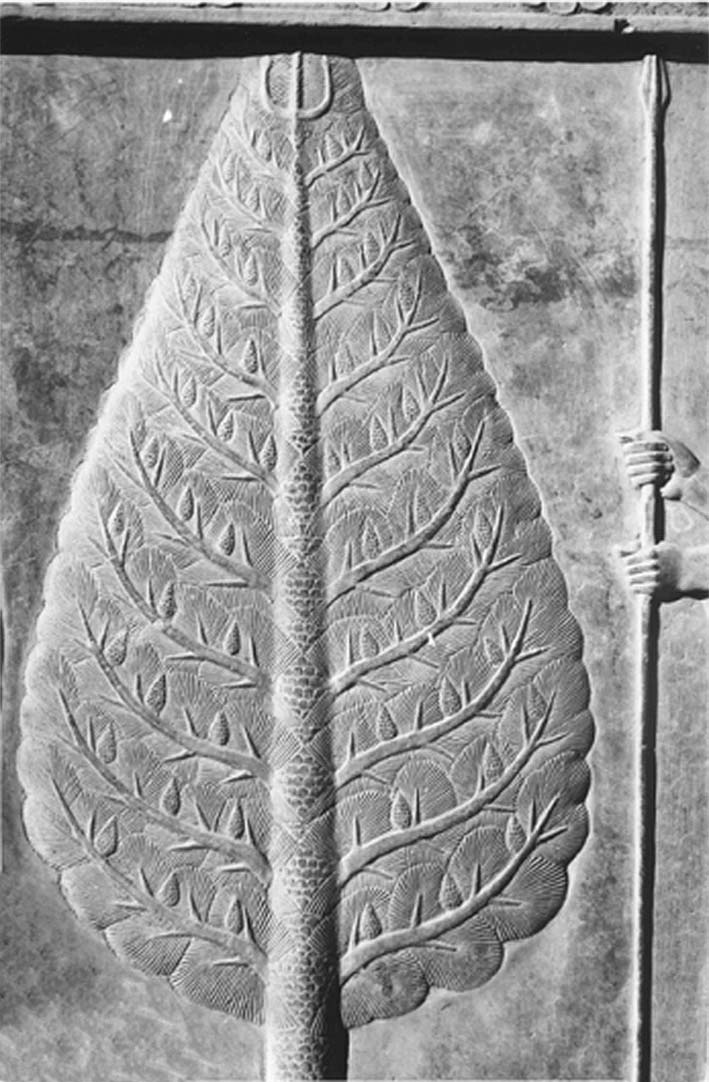

Most scholars agree that the monumental structures remaining from the Achaemenid period, such as Persepolis, Apadana, and Pasargadae, neither resemble traditional temples nor are merely palaces in the conventional sense. Instead, they were designed to serve as venues for ceremonies attended by a diverse assembly of peoples from across the empire. Calendar evidence indicates four major annual festivals, with Nowruz and Mihragan being among the most significant. Nowruz was a festival that incorporated and absorbed many beliefs. The term “festival” itself, derived from the root yazashn/yasht, means “praiseworthy” and involves the celebration of tangible phenomena of the world through ceremonies that foster joy.

Thus, by holding grand ceremonial festivals based on an agricultural calendar—a shared awareness among settled peoples that was common to all communities—this idea was communicated beyond the empire’s borders. Festivals were a crucial factor in fostering unity and cohesion among people.

What has been outlined are clues to how a cultural and intellectual system manifested in various dimensions of civil life, achieving a universal character. Looking at history, all civilizations that later became dominant and global powers, such as the Romans in subsequent centuries, inherited the experience of this first comprehensive system. In various fields, including the provision of a global perspective and its practical manifestation—creating infrastructural networks as a key condition for establishing a world-spanning civilization—the Achaemenid Empire served as a model for them.

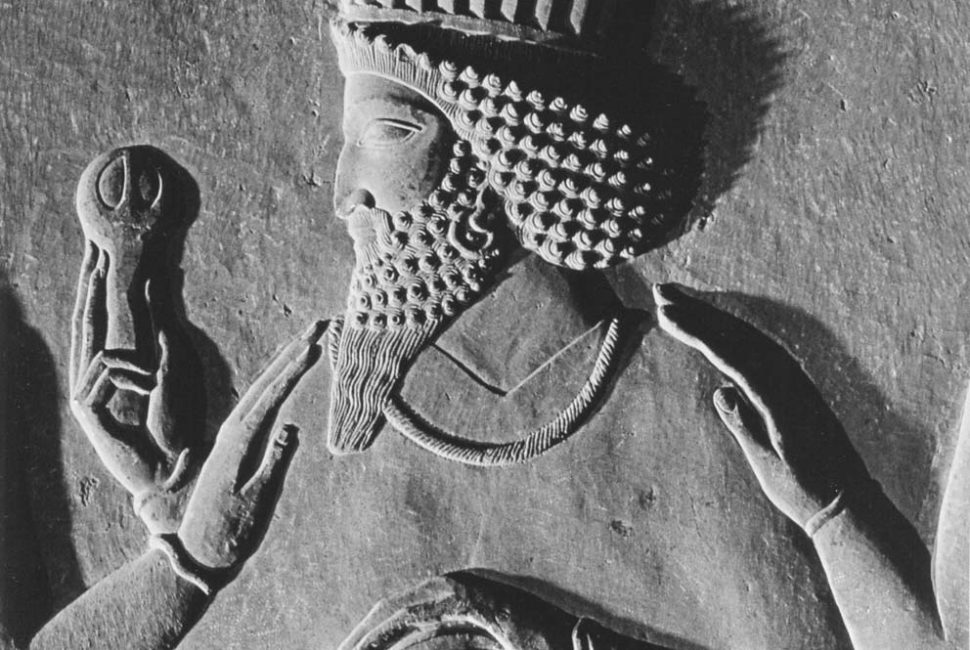

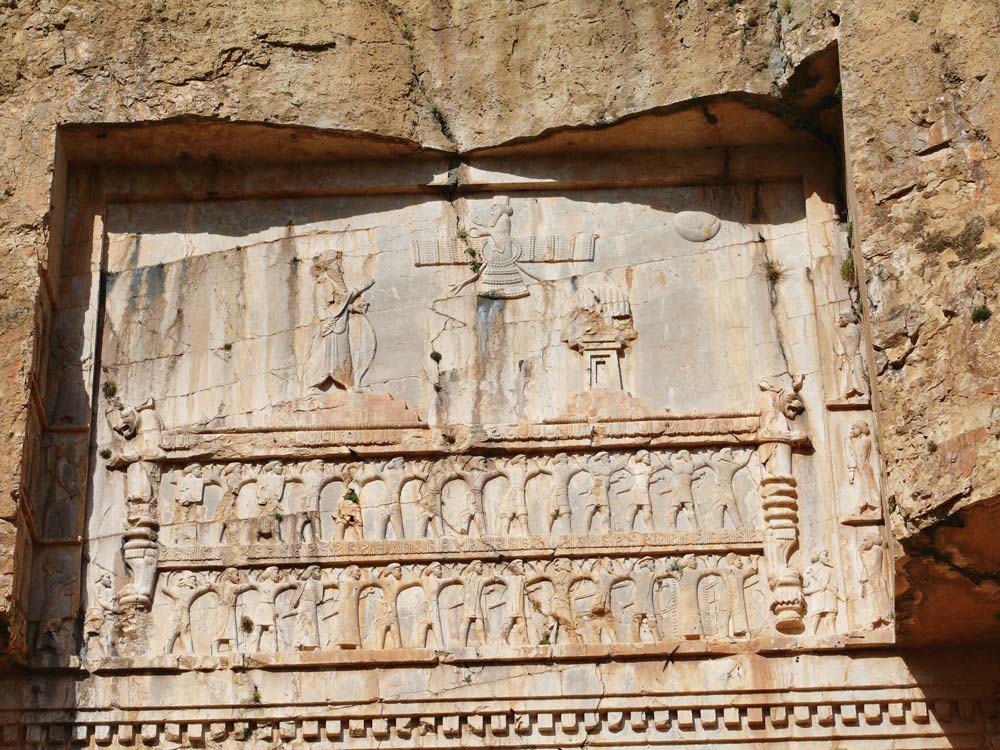

The depiction on the stairway of the Apadana Palace at Persepolis, which is the most significant historical document of the spiritual transformation of this system, serves as evidence that the presence of so many representatives from diverse nations of the contemporary world—ranging from the heart of Africa to the northern Mediterranean shores, the Indus plains, and the distant lands of Central Asia—gathered in one place for recurring annual ceremonies would not have been possible without such spiritual preparation and physical and feasible infrastructure.

The relief on the Apadana staircase at Persepolis is one of the most significant documents of the evolution of consciousness in this system. It depicts a grand Nowruz assembly, featuring twenty-three diverse nations from across the contemporary world, with details that highlight each nation’s distinctive appearance. This scene illustrates the foundations of power establishment within this system of awareness.

Script and Language

Refinement and evolution of language, along with its development and transformation, can only occur over a very long period and through the flourishing of large communities, and the formation of states and religions, in a vast and fertile land.

Language is not merely a tool for expressing daily needs; fundamental aspects of life can be conveyed with a few hundred words, and sometimes even without words, through gestures and expressions. 18

The organization of words, precision in language, and nuances in conveying meaning are directly related to the expansion and evolution of consciousness.

Each ethnic language exists in a natural state within its small boundaries. The ability to break through this natural state and elevate the language depends on the establishment of an expressive logic, known as “syntax.” Syntax, or the logic of language, is the internal mechanism of systematic transformation in a language, enhancing its capacity for meaning transfer and word formation. This logic determines the destiny of the language over time, its ability to bear the weight of evolving consciousness, its flexibility in adapting to changes, and its potential to expand semantic horizons from the seed of this initial logic. Some languages become entirely extinct, while others achieve a long-lasting vitality.

One of the characteristics of the founding centers of culture and civilization is the creation of a language that is powerful in terms of conveying meaning and equipped with a stable logic for the formation of vocabulary, which evolves into syntax over time. Additionally, in most of these founding centers, a foundational script has been established.

In previous lectures, it was mentioned that five different legacies in literature and language emerged from the five founding centers. 19 However, it should be noted that, despite the valuable heritage of these cultural centers, the languages of these literary legacies did not always play the role of a “national language.” For instance, the esteemed Vedic literary tradition did not lead to the emergence of a widely understood national language in the Indian subcontinent. Similarly, some of these written legacies have undergone significant changes, to the extent that reading them solely relying on one language or even a single language family is impossible; for example, the Old Testament has persisted in different linguistic traditions such as Aramaic, Syriac, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin, and it is fundamentally impossible to rely on a single authoritative text for this work. Furthermore, some of these languages, like Early Greek, persisted only during the early ancient period or, at most, up to the late ancient period, and their transition to later periods did not involve the revival of the spirit of the language.

According to experts, the most important living classical languages of the world are Persian and Greek.

Although Persian is among the oldest living languages, its transformation from Old Persian to Middle Persian (Pahlavi of the Parthian and Sassanian periods) and then to Modern Persian has refreshed it through historical breaks and shifts. This renewal is not limited to the nature of the language alone; a significant feature of Persian is that with each linguistic transformation and shedding of its old forms, its literary heritage and intellectual frameworks have been reintroduced in the new language in a fresh form. Notably, this includes the transfer of ancient concepts and themes from the Yashts, Yasna, and Gathas to the epic literature of Parthian (Middle Persian), and their renewal in Modern Persian (in works like the Shahnameh and lyrical literature).

As historians tell us, the Achaemenid monarchy did not rely on a single central city. Instead, it connected a vast expanse through a network of roads, cities, and major centers. This was a significant achievement and a characteristic feature of the Iranian imperial system.

Persian speakers have repeatedly updated their historical ideas and millennia-old heritage according to contemporary knowledge. This aspect, which is unconsciously prevalent in the culture carried by Iranians, becomes more evident in comparison. For example, Greek heritage is only understandable to those who speak modern Greek through the translation of ancient texts. This is a significant difference, as a substantial part of the essence of the work is lost in the translation process, resulting in a text from the past that remains distant and mediated.

The integration of ancient concepts into Middle Persian during the Parthian era, into the Sasanian divine scriptures, and finally into the Shahnameh in modern Persian is not mere translation; rather, it represents a spiritual manifestation that has emerged and evolved over time. Ancient texts have transformed at each stage and have progressed in tandem with the times, so that when we encounter this heritage today, it does not feel like it belongs to the past. As Dr. Javad Tabatabai puts it, these texts are “the future of the Iranian land.”

Another aspect that should be considered in this renewal and linguistic evolution is the development of the “spirit of thought” within Iranian culture. The progression from Old Persian to Middle Persian and then to Modern Persian has been marked by a trend toward simplicity and refinement. For instance, the complex grammatical rules of Avestan, where even nouns were inflected and grammatical genders such as masculine, feminine, and neuter were used, gradually evolved toward ease and fluency in Modern Persian.

This trajectory also reveals signs of the gradual transformation in the worldview of the people who spoke this language, showing how changes in their perception of the world and their existential relationship influenced the language’s logic over time. The refinement of the language and the elimination of cumbersome grammatical rules reflect a spirit of reform, lack of dogmatism, and tolerance in dealing with phenomena within this culture.

Ancient documents from the Iranian cultural system, such as the inscriptions from the Achaemenid period and the poetic Gathas, provide significant evidence of meticulous word choice, both in terms of meaning and the rhythmic quality of words. The continuation and evolution of this process in later literary periods yielded very notable results, and great masters of lexicography and grammar in this culture produced highly valuable contributions up to the Islamic periods.

In Iranian languages, there are three types of words from which other words are constructed:

Roots: such as: سر (head) — دست (hand) — کش (pull) — سنگ (stone) — کار (work) — خور (sun) — دل (heart)

Prefixes: such as: هم (together) — در (in) — بر (over) — پیش (before) — باز (again) — نو (new) — وا (away) — شاه (king)

Suffixes: such as: گر (doer) — آر (do) — ور (actor) — ستان (place) — گار (worker) — بار (load) — ان (plural)

In Middle Persian, new words were formed by combining roots, prefixes, and suffixes. For example, همدل (sympathetic) is formed from هم (together) and دل (heart), and شاهکار (masterpiece) is formed from شاه (king) and کار (work). Although these new words each have their own meanings, they are dependent on the original elements from which they are derived, and understanding their meanings is clearly achieved through the analysis of the word components.

The modern Persian language we speak today has all its words constructed in a similar manner. The reason we understand so many Persian words without having formally studied them or consulted a dictionary is due to this characteristic of the Persian language, which makes understanding its words relatively easy for us.

Word formation in Persian is so natural and simple that even ordinary people create and use new words daily without being consciously aware of the natural properties of their language. For example, if someone listens to conversations in the streets, they will hear hundreds of such words that people naturally create and use (e.g., سگخور [dog-eater] — دستپاچه [flustered] — بادکنک [balloon] — پیادهرو [sidewalk]). These words, despite not having gone through any academic process or having been intentionally created, are used in conversation, and everyone understands the meanings of their components.

All ancient Indo-European languages (Sanskrit, Avestan, Greek, Latin) used similar principles for word formation as the modern Persian language does today. They constructed words by combining roots, prefixes, and suffixes. This approach made understanding the meanings of words in these languages relatively straightforward, consistent, and precise, and also led to a vast vocabulary.

However, all of these languages had a significant flaw that contributed to their extinction: the complexity of their grammatical rules. The grammatical rules, both morphology and syntax, were so elaborate and unnatural that it could be said that no one could communicate freely and effectively using them. As a result, all these languages eventually died out, and despite their invaluable texts, no one speaks or pays attention to them anymore.

From Zabih Behruz: Persian or Arabic language of Iran?

Ancient Persian Script

Language does not follow script; rather, script follows language. In a natural progression, there was initially a language for which a script was developed. In this process, arriving at a logic for recording sounds as written symbols requires the advancement of musical analysis and phonetics. 20

Since the 19th century, we have seen the creation of many tables aimed at classifying various writing samples and providing a clear indication for the origin of scripts. Albert Gaudry, in his book History of Writing, uses one of these tables to classify a vast array of world scripts—from Southeast Asia to those found in Central Asia, Ethiopia, India, Greece, Phoenicia, and more—as branches of the “Proto-Semitic” script. The basis of his reasoning, and that of other researchers of his time, relies on a vague and tenuous categorization. According to this logic, Sumerian civilization is included among the Semites based on this naming convention, without providing precise documentation or a satisfactory definition of what exactly “Proto-Semitic” means.

The term “Semitique” in French and “Semitic” in English, which has recently been translated into Arabic and Persian as “سامی” (Sami), is a relatively modern term. It refers to one of the sons of Noah in the Old Testament narrative. In his works, Script and Culture and Debireh, Zabih Behruz attributes the first use of this term to Aischen Horn, who in 1817 used it to refer to the Arab peoples. This term had no precedent in Arabic, Persian, or European languages and, as noted by the French scholar Renan, is linguistically inaccurate. In the Hatzfeld and Darmesteter Dictionary of 1932, which records the etymology, derivation, and history of each word in the French language and its acceptance in the Academy, there is no mention of the word “Semitique.”

The term “Aramaic,” which was introduced in 1874 by the French Academy to refer to a collection of dialects including Syriac, Chaldean, and others, is also meaningful according to Old Testament beliefs.

Instead of relying on these flimsy classification models, one might turn to ideas with more solid logic. Gordon Childe, offering a pioneering theory in archaeology, referred to the area of early civilizations as the “Golden Rectangle.” This expansive area stretches from the north, encompassing the drainage basins of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the Iranian plateau, to Asia Minor and the Eastern Mediterranean, and from the south to the Nile’s margins, and further east to the Indus Valley.

Today’s research estimates the antiquity of settled life in the “Golden Rectangle” to be at least ten to twelve thousand years. Scattered agricultural experiences, accompanied by the emergence of a new worldview promoting a novel way of life based on food production, prevailed over other forms of subsistence. This idea likely spread from somewhere in the middle of the Golden Rectangle, probably from the northwest of the Iranian plateau, and gained widespread influence. Many cities emerged in this region, showcasing remarkable achievements in science and technology, and over several millennia, laid the groundwork for the first extensive empires in the center of this area. Theories that claim this region’s social system lacked writing entirely and suggest these cities later adopted the script of the so-called “Aramean” peoples should be re-evaluated with skepticism.

The Greek scholar Franz Cumont, emphasizing the account of the Roman Pliny, mentions in his work The Natural History that Hermes, who had seen a Greek copy of the ancient Avesta in the Library of Alexandria, reported that the hymns attributed to Zoroaster listed in the Alexandria library comprised two million lines. How plausible is it that such a vast volume of texts, based solely on oral tradition, could be transmitted through memory alone? According to reports, during the invasions of Alexander the Great, the treasure of Dajanpisht at Persepolis and the treasure of Dajanpisht at the fire temple of Atar-gushasp were sent to Greece in the form of written texts and translated into Greek. Additionally, Greek-Roman philosophers, including Diogenes Laertius, wrote that it was common among the Greeks that Greek sciences originated from Iranian knowledge. All of this points to a significant tradition of writing.

The Behistun Inscription, in its grand dimensions, narrates a significant historical event from the early years of Darius’s reign and the suppression of internal revolts. As noted in the inscription, copies of it were also sent throughout the empire. To date, several examples of it have been identified, including one on papyrus in Egypt and another engraved on a seal.

This inscription is an unprecedented example of a lengthy text prepared in three languages. Notably, significant attention was given to the combination of imagery with the written content in its design.

In Old Persian, the terms “di-pi” and “ni-pasht” are used multiple times, which are noteworthy for us. Darius the Great states in the Behistun Inscription:

“You who read this ‘di-pi’ from now on, may you believe in my deeds.”

“By the will of Ahura Mazda, I have other deeds that are not included in this ‘di-pi’.”

“Therefore, it is not ‘ni-pasht’ so that he who reads this ‘di-pi’ afterward does not consider my deeds to be in vain.”

“You who read this ‘di-pi,’ which I have ‘ni-pasht,’ and see these figures, do not destroy them, and preserve them as best as you can.”

Xerxes also states in the inscription at Van, Armenia: “He (Darius) ordered that this hard stone be carved so that ‘di-pi’ might be written on it.” The term “di-pi-pur” is also used in the account of Ardshir Papakan.

Based on ancient documents, it seems that the term “di-pi” was used to mean “script” rather than “writing.” The word “writing” itself is an Old Persian term (ni-paith), which is composed of two parts: the prefix “ni-“, meaning “down” or “below”, as seen in many Old Persian words such as “ni-haftan” (to hide), “ni-hadan” (to place), and “ni-shistan” (to sit); and the suffix “peshte”, derived from the Old Persian root “pēs” and Avestan “pēs”, meaning “to inscribe,” “to carve,” or “to color.” From this term, ancient libraries and archives were referred to as “Dazh Ni-pasht”.

“Di-pi” 21 or “di-pē”, as used in Achaemenid inscriptions, means “to hollow out” or “to carve out.” We know that in ancient times, the act of writing was done by “hollowing” the medium, and ancient scripts were inscribed by the process of “di-pi-kardan” or “carving” into surfaces like stone, clay, and metal.

The term “di-pīrī” in Old Persian has evolved into various words in Iranian languages, such as “dābīr” (scribe), “dābīrstān” (school), “dībā” (a type of fabric or text), “dībāche” (preface), “dīvān” (a collection or administrative office), “daftar” (register or notebook), and others. In Middle Persian (Pahlavi), this term became “di-pī”, and in Armenian, it appeared as “di-per”.

“Dībā” (in Pahlavi: “dībāg”) refers to something that has writing inscribed on it. “Dīvān” denotes a place where “di-pīrān” (scribes) conducted their record-keeping and calculations. As noted by Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddimah and Qalqashandi in Sobh al-A’shi, the use of the term “dīvān” in Arabic and administrative titles in Egypt also originates from this Persian root.

The Old Persian cuneiform script comprises 36 signs, which made reading relatively easier compared to its contemporaneous scripts (such as Babylonian and Sumerian scripts that had around eight hundred main signs with additional variants, and were syllabic). The phonetic nature of these signs allows for the reconstruction of the pronunciation of the words written in this script.

Some ancient scripts, despite having their signs deciphered, remain unpronounceable because the exact phonetic values of the symbols are unknown. The 36 signs in Old Persian cuneiform are not merely pictorial symbols; rather, they represent an early form of alphabetic writing. Each sign in Old Persian cuneiform corresponds to a letter combined with a vocalic element (e.g., na, ni, nu), marking a transition from logographic to phonetic writing systems.

It also appears that based on this script, a messaging system with encoding capabilities was established, which transmitted messages rapidly across the empire through beacons and fire towers.

Many of the most important Achaemenid inscriptions are carved into rocks along major land routes, as well as at harbors and water canals.

The Behistun Inscription is one of the most significant and largest of these, located on a high cliff along one of the major east-to-west routes, known as the Royal Road. Sections of the paved road remain at the base of the mountain.

The choice of this location has also drawn attention from some researchers due to its connection with water, and its alignment with the first rays of sunlight during the autumn equinox, which marks the time of Darius’s victory over his main rival.

In the next lecture, we will discuss the significance of sunrise illumination in Persian architectural tradition.

Old Persian script is the first writing system to incorporate rules of composition and editorial techniques such as separators, line breaks, and the order of elements. Among the surviving inscriptions, this script stands out as the first non-pictographic one to address both typographic and calligraphic aspects. The Behistun Inscription is one of the earliest documents where the combination of imagery and text has been arranged on a single page, with these elements organized into a cohesive whole.

The integration of imagery with text, or the attention to the aesthetic placement of text on a surface, is not limited to tablets and inscriptions but is also seen on other objects, such as the inscription on vessels, weapons, and other artifacts. For example, a single-line inscription on a silver goblet from the era of Xerxes, as well as inscriptions on stone weights, coins, and various types of vessels, indicate that the arrangement and beauty of the script on objects were also significant considerations.

This perspective continued and reached its zenith in later periods of Iranian art. The distinction in the use of script in these works, compared to earlier works and other civilizations, lies in the fact that it transcended tribal and regional boundaries and adopted a universal and global address. These inscriptions were intended as historical records, considering future times and the unfolding of history.

In this regard, Old Persian inscriptions were typically presented in three scripts and languages, such as the Behistun Inscription, which is written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. This multilingual approach was designed to address a broad audience and ensure understanding across different cultures.

This characteristic of using multiple scripts and languages continued as a notable feature of Iranian culture in subsequent periods. For example, Parthian inscriptions used Parthian script and Greek, while Sassanian inscriptions were written in Pahlavi, Syriac, and Greek. In the Islamic period, Persian, Syriac, and Arabic scripts were employed.

In the inscriptions of Old Persian, a shared literary order based on principles of eloquence is evident, which adheres to a four-part structure: first, the mention of Ahura Mazda; second, the introduction of the royal personage, the king with divine grace, initially in the first person (e.g., “I, Darius”) and then in the third person, from the perspective of a legal entity (e.g., “Darius the king says”); the third section describes the construction and good deeds; and the fourth section offers counsel on truthfulness, commitment, and moderation to the people, and prays for the land, the people, and future generations.

As mentioned, the Achaemenid Empire advanced to a new stage in establishing centers for preserving texts and historical records. Massive buildings were constructed to house written documents, known as “Dazh-napisht” or “Dazh-nushta” (meaning “fortress of inscriptions”). One such example is the Dazh-napisht at Naqsh-e Rustam.

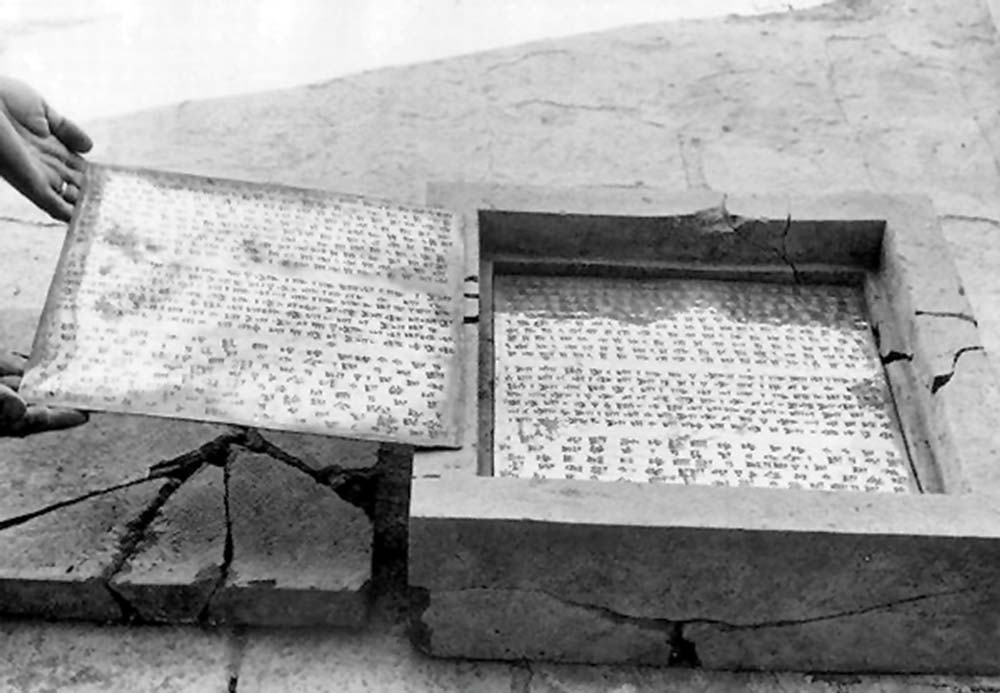

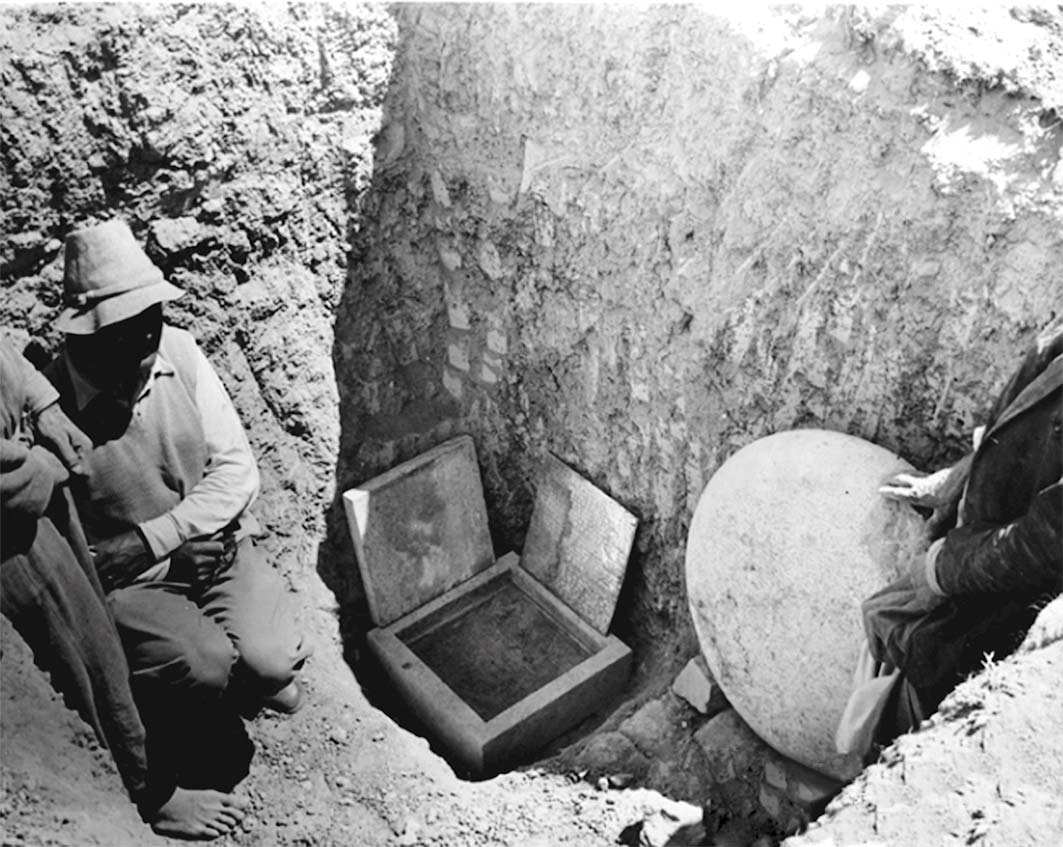

Among the most valuable historical documents that illustrate the evolution of awareness within the Iranian cultural sphere are several foundation tablets that were placed in stone boxes accompanying major constructions. Most of the surviving examples of these documents are related to Persepolis and Ecbatana. In these tablets, as is customary in the literary style of the Persian school, the king initially introduces himself in the first person, and then continues in the third person from the perspective of his legal status. He usually refers to the extent of his domain either precisely or generally, and concludes with a prayer.

Here is the text of a tablet from Darius II:

“Great is Ahura Mazda, who created this earth; who created that heaven; who created the people; who gave joy to the people; who made Darius king; the unique king among many kings; the unique ruler among many rulers. I, Darius the Great, King of Kings; King of the lands with many peoples; King of this vast and far-reaching land; son of King Artaxerxes, Artaxerxes, son of King Xerxes, Xerxes, son of Darius the Great, the Achaemenid king.

Darius the King says: Ahura Mazda granted this country to me; by the grace of Ahura Mazda, I am the king of this land. May Ahura Mazda protect me, my house, and the kingdom He has granted me.”

In the accounts of Ferdowsi, Tabari, Ibn Nadim, Tha’labī, Mas’udi, Ibn Miskawayh, and Ibn Balkhi, references are made to the Djenapeshes of Estakhr, Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid), Naqsh-e Rustam, Balkh, Azerbaijan, Samarkand, and other regions. Evidence suggests that during this period, the collection of knowledge, preservation of intellectual and literary heritage, and the archiving and transmission of this heritage to future generations were given significant attention.

In the fourth section of the Behistun Inscription, there is an emphasis on preserving the historical message, and those who seek to destroy this heritage are cursed. According to the fourth book of the Denkard, Darius III (336–330 BCE) ordered that all of the Avesta and Zend be collected and kept in two copies: one in the royal treasury and the other in a Djenapesh. This tradition continued during the Parthian period under the rule of Balaash, and in the Sassanian era under Ardshir. The historical Avesta was not only a religious text but also an encyclopedia of its time.

The inscriptions from the Persian period primarily focus on politics and governance. However, Greek writers have indicated that epic literature existed in Old Persian. Strabo reports that Persian teachers incorporated legends detailing the deeds of gods and great men into their education for children. Furthermore, research by Ilya Gershevitch and Arthur Christensen demonstrates that there was a distinction in the texts of this period among literary, political, and administrative themes.

Dr. Ahmad Tafazzoli, in his valuable work History of Iranian Literature before Islam, notes that during the Achaemenid era, in addition to government archival documents, there existed a collection of epic narratives such as divine books and royal chronicles, both written and oral, which Greek writers referred to. The accounts of Cyrus, as recounted by Herodotus, likely belonged to this category of epic narratives.

In particular, similarities between the narrative patterns found in Greek accounts and other Iranian stories are noteworthy. For instance, recurring motifs in these stories include:

• Dreams foretelling the fall of one dynasty and the rise of another: This theme is evident in stories about Zahhak, Afrasiab, and Ardashir.

• Orders to kill an infant that are ultimately unsuccessful: Seen in the story of Kai Khusrau.

• Placing or setting a child afloat: As depicted in the tales of Kai Kavadh and Darius.

• Raising a child among shepherds, or having a child nursed by an animal: These motifs appear in the stories of Kai Khusrau, Ardashir, and Shapur.

• The emergence of great deeds and intelligence of the child during play and exercise: Found in the narratives of Kai Khusrau, Ardashir, and Shapur.

Besides Cyrus, stories related to Bardiya (Smerdis) are also recounted in Greek legends. The heroic deception of Zopyrus (a general under Darius) is another example of Achaemenid epic storytelling. Similar narrative elements are seen in the legends of Cyrus as recounted by Ctesias, as well as in the tales of Acheshnavar (King of Hyatla), and the Sassanian King Peroz. Furthermore, certain stories attributed to European kings are derived from the common heroic legends of ancient Iran.

Assistant Krefter, working in the absence of Herzfeld, speculated about the missing location of one of the looted boxes and excavated the site where three others might have been. In the four corners of the foundation of the Apadana palace, he uncovered golden and silver tablets that document the establishment of the palace and define the boundaries of the territory during the time of Darius.

In his lectures on the philosophy of history delivered in Freiburg, which were later compiled by his students under the title Reason in History, Hegel identified the Iranians as the first “historical people.” He considered the main arena of the confrontation between the “self” and the “other” to be the Persian Empire (Persisches Reich). It is important to note that for Hegel, the “Persian Empire” is not a geopolitical concept but a spiritual or conceptual realm. He refers to a realm of unity that, according to Greek historical accounts, was established at the dawn of history among the peoples of the Iranian plateau, Syria, Judea, Phoenicia, Mesopotamia, and northern Egypt.

Hegel views the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire as a new beginning in human history, stating:

“With the Persian Empire, we first step into the continuum of history. The Iranians are the first historical people, and Iran is the first empire to have passed away in history. The rupture between the spirit of history and the history of Asia began in Iran. The Iranian spirit is a luminous and pure spirit, exemplifying a nation that thrives in collective morality and sacred honesty.” 22

Hegel holds particular significance because he opened a new chapter in modern historical thinking, marking a clear division in how historical thought is approached before and after his time. The study of thematic histories—such as the history of art, culture, and science—owes much to his perspective, whether embraced or critiqued by his followers or critics. Standing on the foundations of Western culture, as previously discussed, Hegel also looked at other cultural centers, noting clear differences between them. He elaborates on this in his analysis of China and India, stating that these two centers follow a path of historical continuity without significant change:

“China and India, to the same extent, still remain outside the global history. But here, in Iran, for the first time, a light dawned in history that illuminates and reveals the ‘Other,’ because it was with the light of Zoroaster that awareness in the world, in relation to the Other, began. The light of awareness in Iran shone upon the darkness of Asia, and here the conscious self, under the spiritual relationship, saw itself in the Other. In this regard, Iran represents the break from the natural condition of Asia and its realm, maintaining an importance that will never diminish.”

In contrast to China, which represents a realm of unity without diversity, and India, which exemplifies a realm of diversity without unity, Iran displays a momentary unity in the midst of diversity. This unity is profoundly unstable, a domain of fleeting states and a spiritual sphere that, like the rose, spreads its fragrance from dawn till dusk.

Hegel, in his new interpretation that laid the foundation for modern historical thinking, considers the Iranians as the first “historical nation,” meaning that the Achaemenid Empire served as the place where the “self” confronted the “other.” It is important to note that for Hegel, the “Achaemenid Empire” is not a geopolitical concept but rather a spiritual realm or domain.

With the rupture from naturalistic essence, the concept of progress and historical transformation directed towards the future first emerges within the Iranian domain, where humanity discovers the desire to dominate nature: “The principle of transformation and progress begins with Iranian history, and it is this principle that makes Iran the true starting point of world history.”

Following this transitional period, the entry of Iranian culture into history begins with its interaction with other centers of thought and reflection, initiating a “dialogue of ideas” and a process of “influence and being influenced.” One of the most significant of these interactions is the relationship between Iranian and Greek thought.

In the course of this dialogue, the first philosophical system of the world begins with the confrontation between Plato and the Zoroastrian tradition, thereby opening the two-thousand-year trajectory of the “metaphysical system” in the history of thought. (We will discuss the influence of Zoroastrian thought on Plato’s ideas in a future discussion). From our perspective, the effects of this metaphysical system, which is strongly evident in the history of literature, music, and motifs, are highly significant.

In contrast, at the beginning of the break from the natural state, ancient traditions are usually unfamiliar with the concept of the “Other”; even similar situations are observed in “universal” civilizations (such as the Romans), which entered the historical stage with military force and imposed all aspects of their civilization—such as Roman law, Roman clothing, Roman rituals, Roman language, and Roman cities—on others, without recognizing the otherness of others.

Hegel’s later understanding of the concept of the “Other” was indeed developed in connection with the concept of “natural religion” during the Jena period. In a chapter by that name in Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel describes the three stages of natural religion as: “the nature of the luminous essence,” “plant and animal,” and “the master craftsman.” The treatment of the chapter on natural religion is very complex and enigmatic, and deciphering it is not easy. In the chapter on “the nature of the luminous essence,” which has been equated with the “Persian realm,” there are similarities to the notions of lord and servant. 23

Here, consciousness is likened to the dawning of daylight into the darkness of night. The “pure self” becomes an object to itself through the experience of “self-exit.” Hegel emphasizes that immediate self-consciousness emerges as a lord, while the self-consciousness that has withdrawn becomes a subject. Hegel names this initial relation of spirit with itself as “light” or “luminous essence.” In this relationship, light illuminates everything, making both self and other visible. This dawn (Aufgang) of the luminous essence (Lichtwesen) is in the eastern part of consciousness; consciousness, which had previously existed in the realm of darkness (Finsternis), steps onto the stage of self-consciousness for the first time with this dawn and the recognition of its otherness.

In this context, Hegel identifies the primary site of the encounter between “self” and “other” as the “Persian Empire.” He explains:

“It is from Iran that the first light, which shines from within itself and illuminates its surroundings, emerges. For the light of Zoroaster belongs to the world of consciousness, to the spirit, as something separate from itself. In the Iranian world, we find a pure and sublime unity that leaves the specific existences, which are part of its essence, in their own state of freedom, much like light that merely reveals what objects are in themselves. This unity only governs individuals in so far as it urges them to become strong, to follow the path of development, and to establish their own individuality.

Light makes no distinctions between existences; it shines equally on the righteous and the sinful, the high and the low, and grants blessing and well-being equally to all. Light only becomes life-giving when it connects with something ‘other’ and separate from itself, and influences and nurtures it. Light is opposed to darkness, and this opposition reveals the principle of effort and life to us. The principle of evolution begins with the history of Iran, thus the beginning of universal history, in its true sense, starts here.”

The principle governing this transition is that the universal essence, which we previously saw in Brahma of the Hindus, now becomes comprehensible to human awareness; that is, it becomes the object of human knowledge and acquires a positive meaning for humans. Brahma is not worshiped among the Hindus; Brahma is merely a state of individual life or a religious feeling, and an existence that is non-objective. This condition, in relation to tangible life, is akin to nothingness. However, when this universal essence becomes objective, it acquires a positive nature; humanity is liberated, and thus it seems as if one encounters a transcendental existence that has become tangible for them. Such positive universality is found in Iran, and as a result, we observe that humanity is separated from the universal essence, while at the same time, the individual human recognizes themselves as being identical and of the same essence with that universal essence. 24

From this point in awareness, or from this phase, the stylization of motifs acquires a historical dimension. This means that “mudras” find the possibility of spreading throughout the entirety of a region’s artworks. This is a very significant transformation in consciousness, something created by the spirit rather than being a continuation of nature. These mudras are no longer extensions of natural behavior but are rather expressions of the human spirit, symbols that can embody understanding of ideas and the absolute. The spirit positions itself in opposition to the “other,” and seems to be in the process of self-manifestation.

Thus, a system is formed here where the first manifestation is that of “Him” or, in other words, the first manifestation is that of Ahura Mazda (as reflected in the verse: “From the eternal light of His beauty, the radiance began”). In this temporal domain, which will culminate with the human destiny of collaboration with Ahura Mazda, the “Savior” (Sushant) represents or reflects the human duty; that is, the human poet, who is both a lover and the sole seeker (“Love appeared and set fire to the entire world”). He is the unique spirit influencing existence; he is the singular chooser who moves toward being (Ahura Mazda); he is the one who, with the power of good thought (Vohu Manah or Bahman), calls everyone towards the standard of truth (Asha Vahishta or Ardibehesht); he is the sole guardian of the eternal Holy Spirit (Spenta Armaiti or Espand); and the one who brings completion and abundance (Haurvatat or Khordad); thus, he is immortal and possesses an eternal soul (Amrta or Ameretat). This relationship between humanity and existence, and the manifestation of the Divine Spirits, encapsulates the core themes (motifs) in the art and culture of Iran.

The design of the Achaemenid kings’ tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam features a large cross-shaped relief carved into the heart of the mountain. This cross marks the intersection of two arms of the cross, which, as previously discussed, is one of the fundamental symbols of the transition of meaning of the center and the point of manifestation. In this intersection, a cavity was carved into the rock to serve as the burial place (later, in Christian tradition, the body of Christ is also depicted at the intersection of the two arms of the cross).

Above each of the four tombs, a consistent image of a hero-king at the end of his journey is depicted, with all figures facing the sun and raising their hands towards a covenant ring held by a divine figure (Frawahr). Unlike all the men who carry his throne and bear weapons, this hero has set his empty bow on the ground; the end of the battle signifies the end of his duties in the world. The king has used up his arrows and completed his battle in this campaign.

Comparing this image with the depiction of the noble king on coins of the period, which shows him with an arrow in one hand, a drawn bow in the other, and a quiver full of arrows on his shoulder, further highlights the symbolic significance of the tomb reliefs.

The establishment of the first school or style of Iranian art and culture, which we call the “Persian/Parsa School,” took shape within the framework of the Iranian worldview. This process began before the Achaemenid era and continued until the end of their reign. Within this school/style, themes emerged that, despite transformations, continued to influence Persian art and literature for millennia. In the artworks of this period, while motifs from the familiar visual memory of the contemporary world were borrowed, new meanings also emerged. This characteristic is typical of a historical school, which can channel multiple streams of consciousness into a major river, thereby creating new possibilities for opening up new horizons. Behind every foundational school, there is a network of influential centers; for example, the antecedents of the Romanesque style (or the first historical school or classical European art) can be traced to the art of Mycenae, the Aegean, Etruscan, and other scattered centers.