An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

In the beginning of this chapter, it might be necessary to briefly touch upon the topic of the place of “cultural heritage” in the perspective we are pursuing in these lectures. Here, we emphasize the word “culture,” and it is likely that we will study works that do not fall under the conventional categories of “art.” We draw the readers’ attention to the fact that existing and accepted theories of art history explain a specific kind of human artistic and cultural products. These theories are well-suited to the history of Christian European art, but applying them to other contexts is inappropriate and, more importantly, unproductive.

Whereas our subject fundamentally involves examining the development of a specific type of awareness that has emerged in this region and is reflected in its culture and art.

In Western historiography in general, and consequently in its subfields such as “art history,” the approach to the East and its early civilizations is typically as a prelude to the rise of Greek civilization, which is regarded as the mother of Western civilization. Titles such as “The Orient, Cradle of Civilization” and similar expressions indicate how the West perceives itself as the heir to a civilization that was born in the East and then transferred to Greece. With such logic, it is natural that in existing art histories, what happened during this period in the Iranian Plateau, India, Egypt, and Mesopotamia is treated merely as a few pages of introduction to the entirety of this history. We must be aware that a period which might be considered an introduction or background for others was, for what later manifested as the “culture of Iran,” a vital and decisive era spanning several millennia. 1

From this perspective, our focus on this ancient period is significant and meaningful, warranting extensive research and much deeper contemplation. Unfortunately, the archaeological excavations and foundational research conducted in Iran are still very incomplete, and what has been done has largely been subsumed under Western historiography.

In the context of Iranian arts, the interweaving of the pictorial structure of miniature painting with calligraphy and bookmaking, and that with literature and poetry, and that with music, and that with architectural motifs, and that with garden design, and that with the quadripartite divisions of natural elements, becomes evident to any interested researcher even at first glance. This connection is of a deep dependency, making the study of one incomplete without addressing the others. (Even in this cursory look, it is clear how meaningless and inappropriate it is to try to separate works equivalent to Western painting and sculpture from the rest of this ensemble).

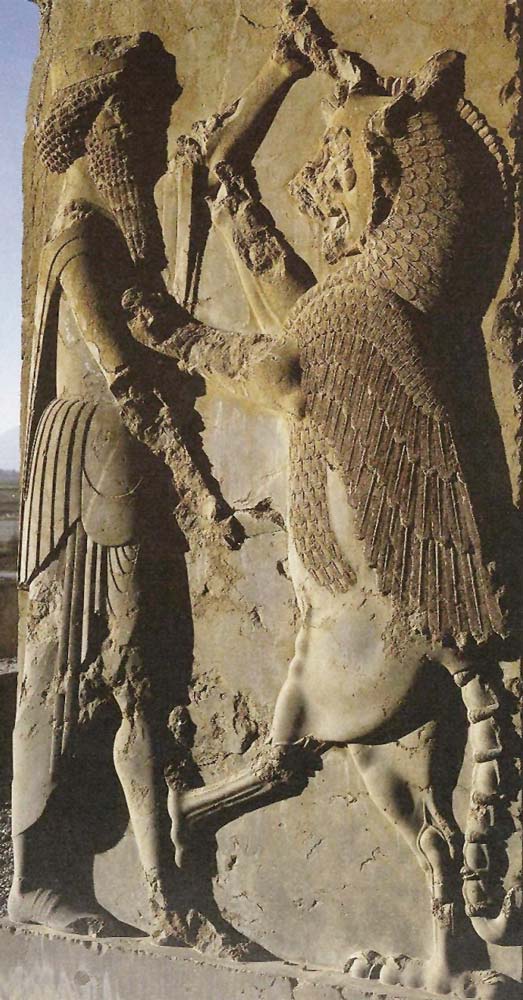

Moreover, from a vertical historical perspective, culture, with its various manifestations, appears as a meaningful fabric. In the ancient periods under our discussion, although the initial manifestations of consciousness in counting, astronomy, calendars, motifs, the emergence of historical language and literature, and the invention of writing were results of the needs of sedentary life, the fruits of these developments quickly manifested in the evolution of various forms of awareness. This is evident in naming the months of the year as countable units, holding festivals at regular intervals of finite time, naming constellations, and depicting them in the forms of animals. Without understanding this evolution of consciousness, a separate study of a single motif, such as the carving of a lion grappling with a bull or the battle between a human and an animal, would be a feeble and futile effort.

With these preliminaries, let us now delve a bit deeper into the period we have termed the “First Genesis.” As previously discussed, humanity transitioned from the cosmic era to the mythological era, characterized by a gradual shift in general and universal human awareness. During this period, diversity in various forms of awareness began to take shape gradually. In different regions of the world, step by step, influenced by environmental factors such as climate, natural resources, and historical events, diverse forms of awareness emerged. This diversity manifested in various cultural forms, ways of interacting with the environment and other people, and the manner in which individuals understood themselves.

This transformation in awareness and the creation of abstract concepts progressed in parallel with changes in the concrete organization of daily life, methods of obtaining sustenance, and the increasing complexity of human societies.

Regardless of the evolution of consciousness among the people who founded cities, and in whom concepts such as “domestication,” “dominion over land,” and “sovereignty” gradually emerged, and also regardless of the process of each ancient motif bearing fruit into newer meanings, addressing a single motif separately (for example, the battle of the hero/sovereign with an animal) would be a feeble and fruitless effort.

The sequence and delay of subsequent large settlements entering the agricultural and sedentary period are matters related to archaeological research and are not the focus of our discussion. As far as we know, agriculture has repeatedly been accepted and rejected. Early villages were often completely abandoned, and people returned to a nomadic lifestyle.

Many small, vulnerable villages were completely wiped out due to climatic changes or invasions by attackers. In some regions, such as parts of the Far East where rice could be cultivated multiple times a year, and along the Nile where the natural conditions supported agriculture and sedentary life, continuity in agricultural patterns was somewhat more feasible. However, generally, in most areas, maintaining an agricultural lifestyle was challenging. Without new knowledge that supported agricultural life, the transition from nomadism to settled life was practically impossible.

Attention to the views of some scholars, such as Jacques Cauvin, who emphasize the role of a “new idea” in this transformation that shaped the future of humanity, seems to be illuminating. As explained in the previous discussion, it was this new awareness, centered around the Golden Rectangle 2, that provided sedentary life with advantages over other forms of existence and effectively ended the oscillation between foraging and production in this region.

A different perspective on the world emerged, along with a way of addressing life within a harsh natural environment. This perspective resulted in a type of ethical definition that viewed land cultivation as the act of improving the world and considered improvement itself as a valuable endeavor. The development of this new awareness took millennia, giving rise to abstract concepts and new social contracts. These in turn nurtured the secondary achievements of sedentary life, which influenced the ancient world up to its known boundaries.

The initial foundations of what we refer to as “Iranian Culture” or the “Cultural World of Iran” were gradually being established during this period, which we previously called the “First Genesis.” These fundamental changes, as far as archaeology indicates, appeared around the seventh millennium and initially manifested as transformations in the mode of living;

_ Changes in the method of selecting settlements and shifting to new habitats, bringing previously uncultivated lands under cultivation, and settling in new locations that were not necessarily centered around a sacred site. 3 In earlier settlements, the practice of burying the dead in the same living space and on the floors of rooms was a way to reinforce the connection of future generations to that place. Thus, an urban structure was created that was intended to be permanent, resulting in settlements being continuously and incrementally rebuilt on the same location.

_ Changes in burial practices, with the marginalization of the tradition of burying with certain previous magical symbols, such as animal skulls.

_ Changes in the organization of populations based on new knowledge and agricultural experience, rather than relying on the necessities of invasion and attack.

_ The development of a new meaning of “work” and the value of labor on the land and the cultivation of fields.

_ The marginalization of the previous logic of classifying human settlements (archaeologists confirm the existence of these classifications in earlier communities of the region, and similar signs of such social distinctions are again evident in urban developments after this nearly three-thousand-year period).

_ Changes in the methods of utilizing water and soil, including innovations in obtaining and managing freshwater and its control and distribution.

_ Changes in ancient beliefs regarding “sacrifice,” and the end of blood rituals that had been a continuation of the natural state of human existence.

In ancient Iranian stories, the knowledge of the farmers about the achievements of settled life and the organization that emerged gradually is reflected in the chronological division of past history, naming each period after the reign of a king. In the updated version of these stories found in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, regarding the selection and domestication of animals, wool-spinning, and the creation of garments and carpets during the reign of Tahmuras, we read:

The world I will cleanse of evils by my counsel, / Then I shall set up a gathering place for my people.

From every place, I shall drive out the demons, / For I intend to be the sovereign of the world.

Whatever in the world is beneficial, / I will make it evident, freeing it from bonds.

From the fleece of sheep and lambs, / I will cut and spin wool, and create clothing.

With effort, he made garments by his will, / He was also the guide for expanding them.

From the swiftest of runners among the seekers, / He fed them green herbs, straw, and barley.

He observed the thieves, / Selecting the black-eared and swift cheetahs.

Among the birds, he chose those with noble flight, / Such as falcons and majestic hawks.

He brought them and began to teach them, / The world was left in wonder at his work.

Having done this, he gathered the hens and roosters, / Those that crow at the sound of the drum.

He brought them all to the people, / Choosing only what was useful.

He commanded them to be gently cared for, / To be called only by soft calls.

He said, “Praise this, / And worship the Creator of the world.

He gave us the means to tame the demons, / Praise him who showed us the way.

In the transition from a peasant society to an urban historical society, what gives rise to a structure known as a “country” involves the creation and establishment of phenomena that enable humans to measure and understand their surroundings. This also includes the emergence of a narrative that helps in the continuity and connection of the human spirit, depositing experiences and observations into a repository of stories and records. These phenomena become measurable and relate to the passage of time.

What makes the compilation of such a narrative possible is the development of a historical language capable of conveying meaning, alongside the emergence of writing, counting, astronomical tables, and the formation of rituals. The Iranian Plateau, with its expanding villages and the cities gradually forming during this period, creates, through competition, exchange, and conflict, the core of diverse civilizations across a vast territory. This marks the beginning of this transformative journey.

The acquisition of freshwater through various methods is explored, and one of the most innovative methods, namely the creation of qanats, is developed, laying the foundation for the world’s unique qanat-based civilization. It is known that advancements in qanat construction were dependent on the development of trigonometric knowledge. Mathematics and numerical calculations, branching out as needed, evolved and expanded, including in the context of solar calendar systems that met the needs of agricultural life in calculating the seasons. This change required more advanced numerical calculations. Among the oldest records on counting are the documents of decimal numbers and the concept of zero (zaphirin) found in Avestan texts.

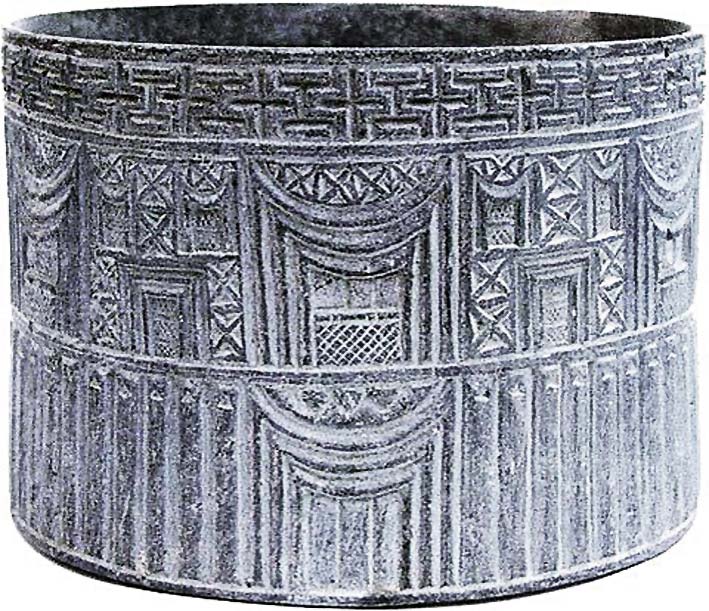

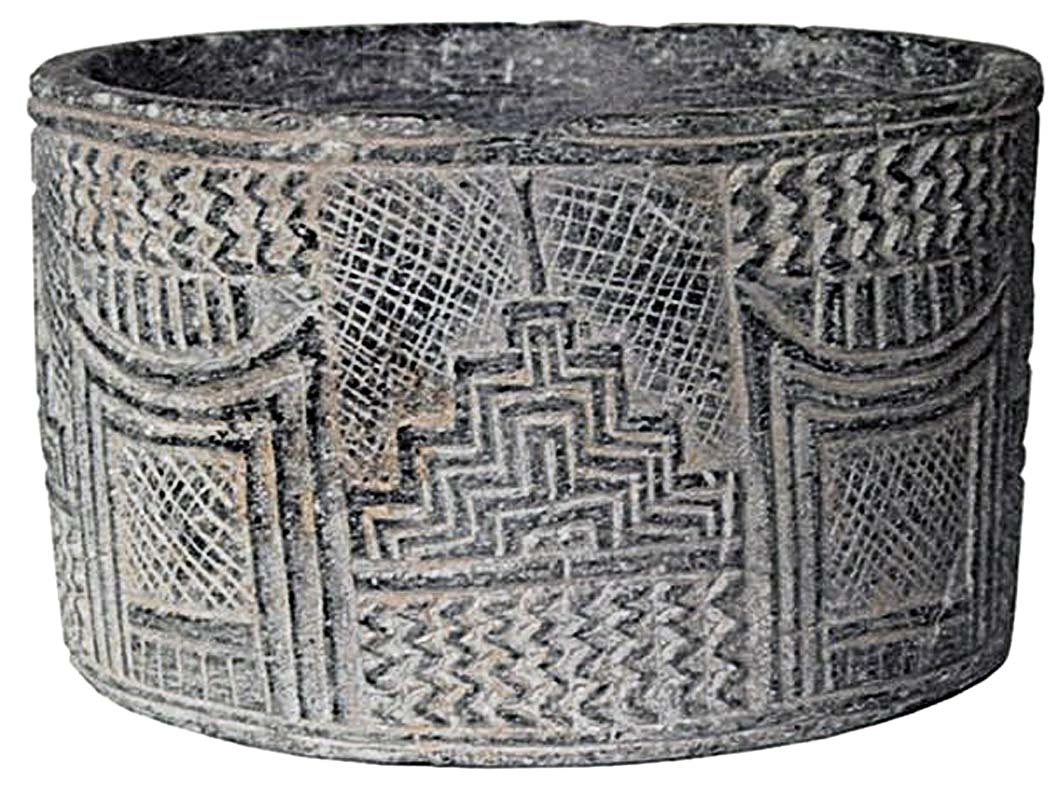

The civilization of Aratta (centered in Jiroft) in the Konar Sandal region—along the Halil River for 400 kilometers—boasts a collection of highly sophisticated motifs and designs that predate the Sumerian civilization. Research by Professor Karl Luschei suggests that some of the artifacts found in the Sumerian civilization may have origins in this region. A royal inscription discovered by his archaeological team in the 1960s is dated to 4500 BCE based on carbon-14 testing at the University of Pennsylvania.

The decorative motifs on many artifacts from the Jiroft civilization evoke architectural elements such as ornamented walls and ziggurat-like stepped structures. During excavations conducted by Dr. Yousef Majidzadeh in the 1980s, two platforms of a large ziggurat, with bricks measuring 40 by 40 cm and walls approximately ten and a half meters thick, were discovered in the Konar Sandal area. The findings are very close to the descriptions of the city of Aratta in Mesopotamian sources, which describe it as a desirable city with tall, colorful walls and lapis lazuli crenellations.

By sharing the knowledge of solar calendar organization, a broad capacity for synchronizing rituals and festivals and enhancing mutual understanding was made possible. Without a basis in precise measurement and astronomical calculations, the extension of this synchronization to distant locations would have been unfeasible. Thus, one of the most significant achievements of this period was the creation of “synchronization,” which emerged through the meticulous refinement of the calendar.

Shared festivals, rooted in agricultural experience, were initially celebrated at the start of the four seasons (Nowruz, Tirgan, Mehrgan, Sedeh). Within these festivals, not only time but also the world was divided into four primary elements (the four sacred essences of the earth). 4

Such early divisions made the seemingly endless world perceivable and measurable. This led to the formation of a kind of ontology and division of cosmic forces, which defined a specific concept of cosmic order. This order was designed to be shared, utilized, and accepted among diverse natural phenomena, ethnicities, and cultures. Through this new order, and in a gradual process, celestial meanings (in cosmic-mythological narratives) were connected to the earth and everyday life, making them tangible and accessible.

The understanding of measurement, and the development of methods for quantification and comparison, led to the creation of a universal concept and image of scales for assessing all aspects of material and biological dimensions, from volume and time to space, and extending to more complex notions related to individuals and societies.

Measurement was a significant advancement in human awareness, enabling the comprehension of multiplicity and providing new meaning to unity and coherence within this new framework. This broad scope, ranging from measuring a material element to quantifying concepts and desires, is influenced by this type of awareness.

On a broader scale, the emergence of the concept of measurement facilitated the formation of “contracts” and “oaths,” which underpin social agreements and public laws. In other words, it is through this development that the “principle of covenant” entered the social domain.

In parallel with these developments, and in direct relation to the experience of gradually confronting the aridification of the land and the type of climate that could be managed to become green or, otherwise, remain dry and barren, the initial roots of the “dualistic thought” were forming. This dualistic thought later evolved into a more complex “heroic ideology,” which became one of the foundations of Iranian culture.

The intricate network of exchange, transmission of concepts and discoveries, and mutual enhancement laid the groundwork for the formation and development of larger social units beyond the initial tribes and clans.

In previous discussions, we briefly mentioned the importance of intellectual games and the transmission and expansion of concepts through them. Games, as collective activities rooted in joy, play a crucial role in transferring experiences and worldviews over time and expanding them geographically.

During this period, numerous and diverse examples of game boards have been found in the civilizations of the Iranian Plateau. Similarly, based on evidence from toys and musical instruments, one can hypothesize about the development of early stories, songs, and lullabies. These elements are key in the continuity of experience and culture from mother to child and simultaneously contribute to the formation of melodies, sounds, and narrative techniques.

Trade / Interaction / Security / Tolerance

Trade:

Agricultural life, compared to a nomadic lifestyle, tends to be more stable and less varied. However, it also comes with risks that could potentially annihilate human groups entirely. The isolation of settlements, the threat of natural disasters, and the loss or plundering of produce make agricultural villages even more vulnerable.

In the previous discussion, we briefly touched upon the communication routes. During this period in the Iranian Plateau, at least three ancient communication routes can be identified across the geographic latitudes of the south, center, and north. These routes connected small villages to each other, to larger cities, and to civilizations beyond the plateau. Today, the “Silk Road” is widely recognized and established as the main trade route connecting the East to the West,5 and no other communication route is nearly as famous in comparison.

The importance of trade is evident, especially when studying ancient periods. The exchange of goods and the traceable movement of materials provide clearer insights into historical interactions. For example, minerals extracted from mines in the Vararud region appear in places like Shahr-e Sukhteh, Jiroft, and Babylon, tracing their own paths. Numerous such examples exist; copper from central Iranian mines has been found in Palestine, and pottery made from central Zagros clay has been discovered in Anatolia. In Shahdad, we find industrial workshops dedicated to cutting and polishing precious stones, indicating that these cities were connected to an extensive network beyond the Iranian Plateau.

The topic of “trade” and the pursuit of commodity exchanges, facilitated by modern scientific tools and laboratory capabilities, also has a foundation in our prevailing mindset. In the world as we know it today, trade seems to dominate; in a world where Anglo-Saxon culture often prevails, trade appears to be the primary and most important form of human exchange. It drives most of today’s human migrations, underpins many treaties and wars, and is behind various glittering ideologies. However, with this contemporary perspective, we can at least consider a broader scope and a more open view, asking ourselves what additional insights our current knowledge about the past offers beneath the surface of these prevailing assumptions. Is our exploration and research into the past limited to findings that only confirm the exchange of goods between cities and population centers?

The concept of the world becoming “measurable” marked a significant transformation in human awareness, turning multiplicity into something comprehensible and redefining unity and singularity within this new framework. This broad range—from measuring a material element to quantifying abstract concepts and desires—reflects the impact of this awareness. On a larger scale, the emergence of the concept of “measurement” made the establishment of “contracts” and “oaths” possible, which in turn enabled the formation of social agreements and public laws. This was the first step on the path through which the “principle of contracts” entered the social domain.

The expansion of the concept of measurement and quantification in various dimensions—such as weight, length, and time—along with more abstract meanings, took place during this period. In the context of shared rituals and celebrations held at specific times, the understanding of time measurements and the establishment of this mutual understanding manifested in the form of a “common contract.”

Meeting

Modern sciences remind us that the need for “meeting” is inherent in human nature, stemming from the desire to overcome loneliness and to connect. According to biologists, the physiological changes in humans standing on two legs are a result of this natural desire, gradually giving them a taller stature that allows for a broader view of the horizons ahead. In its natural state, “meeting” only makes sense in terms of stepping out of the initial biological process, which involves finding areas with greater potential for life beyond one’s immediate ecosystem and acquiring the basic necessities for survival. However, this desire, when transcending its natural state, can take on a deeper and broader meaning. The settled farmer does not merely live within the confines of nature; instead, he grapples with it and seeks more than mere survival. His efforts are not only about struggling for existence but also about organizing the spirit and breaking free from the endless cycle of time. In such a rupture, “meeting” becomes an opportunity to redefine the relationship between humanity, existence, and time within a new framework of awareness, marking the beginning of the journey of the soul.

In the myth of the “Hero’s Journey,” there are common and constant archetypes, typically including: the desire to meet, separation from the origin, the journey itself, and the discovery of the land of immortality. In the mythical stage of life, humans are still trapped in the confines of their natural state and are deeply thirsty for eternal life. The hero ultimately returns to the origin after accepting the fate of death. Those waiting for him also share in his experience through his return and the recounting of his trials, accepting what he has seen (as in the story of Gilgamesh). The hero’s journey is a recurring narrative, but in the phase following the experience of urban life, it takes on deeper meanings. In this phase, the story is perceived as a rebirth or transformation of the human awareness system, representing a new birth of understanding.

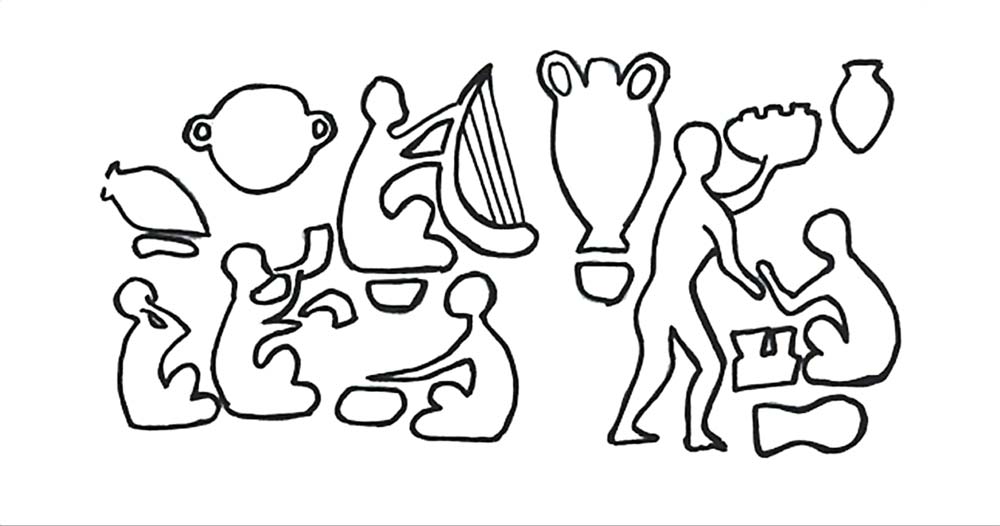

The golden cup features an illustration of awareness of the cycle of life, depicted through the life stages of a goat from birth to death.

It is quite evident that extending the conditions of the modern world to the ancient world is incorrect. One area where this misunderstanding may occur is in our interpretation of the term “trade.” The desire to obtain certain goods has always been a cause of exchange and conflict, but there is no evidence that essential living necessities were transported over long distances on major trade routes. In the ancient world, basic needs such as food and energy resources were generally met through local access.

Therefore, we need to reconsider ancient trade, as the exchange of goods that we associate with modern trade was very limited, and expectations from trade were directed toward different items. Evidence suggests that the main goods traded on major routes were primarily products and artifacts that satisfied the aesthetic desires of settled people: various fine fabrics, and items with astonishing craftsmanship made of precious stones and metals, and jewel-encrusted ornaments.

The journey initially begins as an external expedition, but it acquires an internal dimension; the world reveals itself within words such as: asha, arta, and farrah, and reaches a vision. The epic tales of the hero’s journey, manifesting in the form of Rostam and Esfandiyar’s seven labors, the seven stages of Khosrowani wisdom, and the traversal of the seven cities of love in ancient Iranian narratives, have gradually evolved over millennia, each time taking on new forms. From the Yashts to epic texts and then to lyrical literature, this continuity represents one of the manifestations of the historical evolution of spirit and consciousness.

This is an example of how a universal human concept—in this case, “encounter”—transcends to another level, gaining the capacity to encompass richer metaphorical meanings. The world within the concept of “encounter” reveals itself to the human-hero as a clear message that can evoke new questions, and with its reflection and transmission to others, history begins.

The response to the need for “encounter” also reveals the capacity to open many other realms in humans. The emergence of a broad range of cultural achievements can be viewed from the perspective of this need and reinterpreted accordingly. One of the most significant human achievements, writing, is noteworthy in this regard. With the advent of writing, a very special phase of history began in which not only the possibility of recording, organizing, and transmitting concepts and experiential heritage acquired new meaning, but a new chapter in human intellectual life was also opened. Writing, in itself, is a form of organizing pictorial rules, and this pictorial characteristic was prominent in the early scripts of various civilizations, among the most famous examples being the Egyptian hieroglyphs in ancient culture.

A long time passed from the first emergence of pictorial scripts to the organization of letters, vowels, and consonants. We will leave further explanation about the history of the evolution of writing to the comprehensive examination of what lies ahead, and we will follow the changes in each period to the best of our knowledge in future discussions. However, what is noteworthy here is the connection of the scripts in the period under discussion, both in form and in the logic of presenting concepts, with the prevailing consciousness of that era.

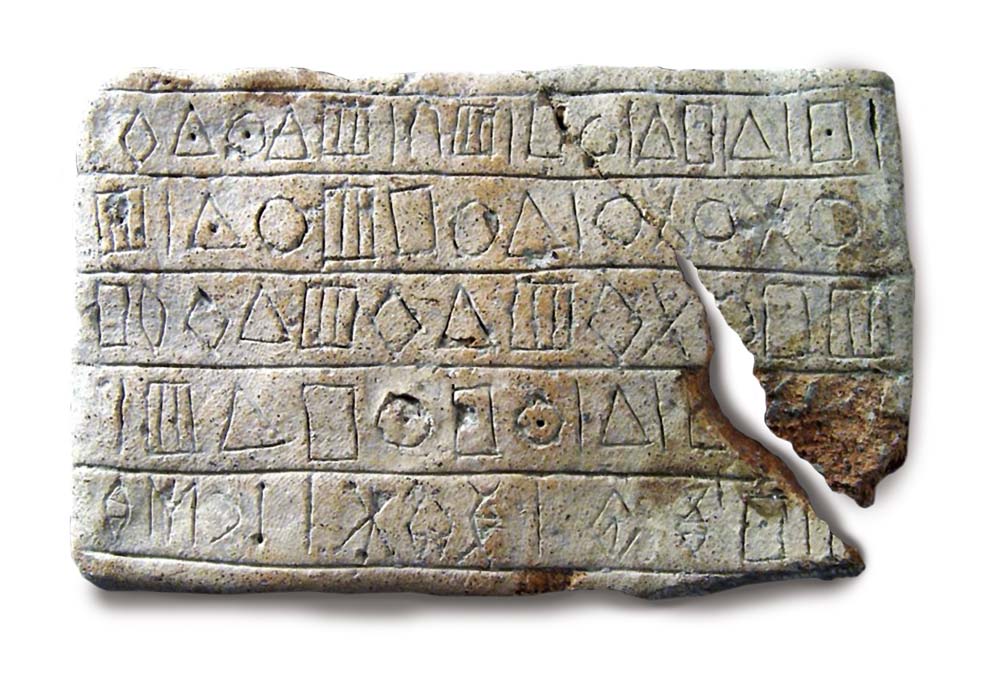

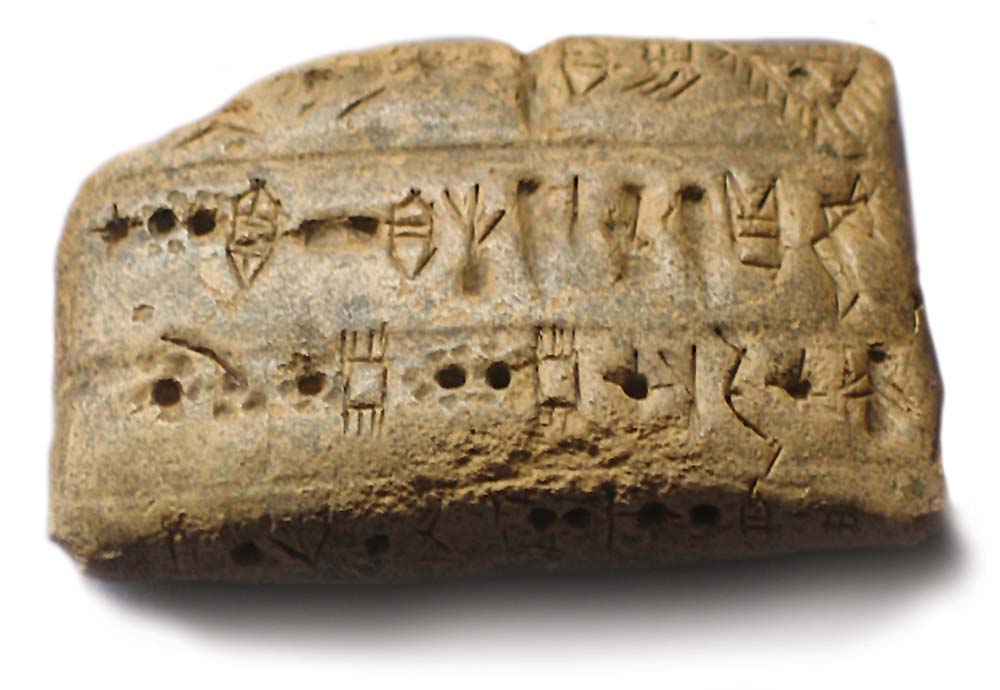

In this context, within Iranian civilization, two significant origins can be identified as pivotal points in the evolution of consciousness. One is the region encompassing the western and southwestern areas and the Zagros up to the central plateau of Iran, where the Proto-Elamite script developed. The other is the southern and eastern region, which was the cradle for the development of a script, examples of which have been found in the Konar Sandal area of Jiroft.

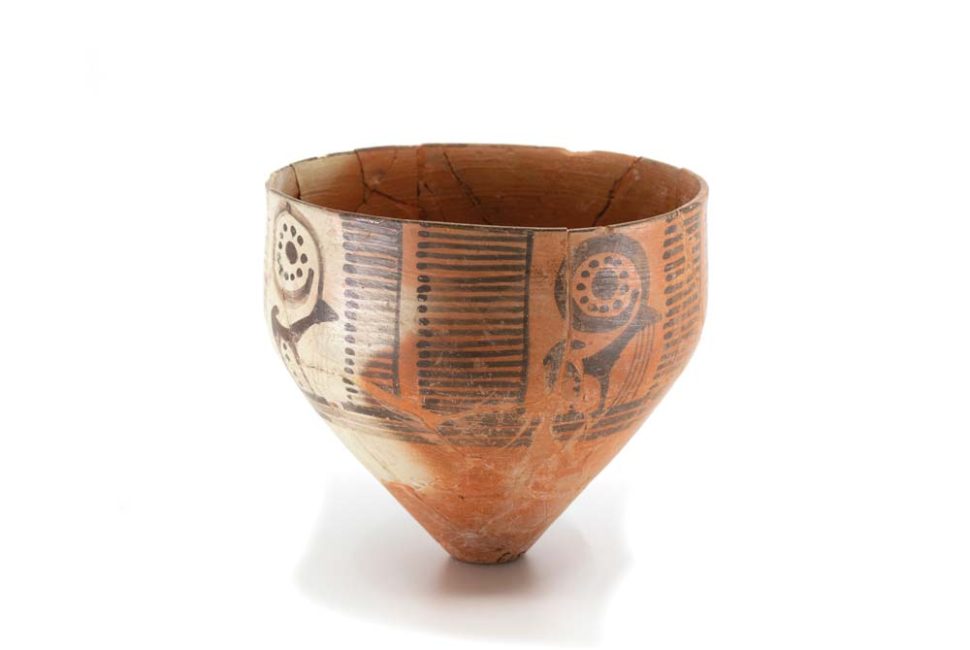

A precise interpretation of these documents and the formulation of a theory explaining the emergence of these scripts, as well as enabling their accurate reading, requires further research. The history of these documents coincides with the era of the three millennia of painted Iranian pottery. The examination of Proto-Elamite texts and their pictorial content is semiotically connected to the symbolic motifs on the pottery.

The tablets discovered from the Konar Sandal region of Jiroft follow a different logic. The only commonality, in terms of motif analysis, between this unknown script and other samples is the logic of quadrature. The script used in Konar Sandal, considering the limited examples that have survived looting, consists of four motifs: square, circle, triangle, and line segment. Movement within this script follows a cruciform pattern (this characteristic is also observed in Proto-Elamite examples).

The internal logic of these writings can be understood through the shared functions between the script’s semiotic system and the pictorial heritage of pottery. Additionally, comparing these examples with early Chinese kanji, which shows significant similarities, could provide insights.

In the kanji system, the complete square is both the starting point and the first kanji, with several thousand other characters evolving in relation to this initial square. This quadrangular nature is noteworthy because most early ancient scripts followed a similar logic.

In Dr. Majidzadeh’s excavations in Jiroft, tablets from the ancient civilization of Aratta were discovered, containing a script that predates the Proto-Elamite period (circa 2500–2700 BCE). The writing signs of this script—whose phonetic, vowel, or symbolic nature remains unknown—are based on the fundamental shape of a square.

It should be noted that the earliest writing samples in all civilizations and cultures established are based on a cruciform movement rule and square form (such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese kanji, and the square script known as Hebrew). It is also noteworthy that in modern times, for the creation of Braille (which is meant to be readable by touch for the visually impaired), the design of letters with raised dots has also been done within a square framework.

The square form itself results from drawing a cruciform pattern. The origin of the cruciform pattern is a central point, which, as previously mentioned, symbolizes the center and first appeared in the form of a “+” or cruciform shape. As noted in earlier discussions, the point, as a symbol of the center, has a mythological origin and plays a decisive role in the human unconscious.

In the study of script and the role of the square and cruciform patterns, the kanji of Chinese civilization is also highly significant.

The first kanji in the Chinese writing system is a complete square, known as 口 (Kǒu), which means “mouth” or “place of human sound.” This kanji acts as an intermediary between heaven and earth. The next two kanji are 天 (Tiān), meaning “heaven,” and 日 (Rì), meaning “sun.” Other characters are similarly derived, such as 白 (Bái), meaning “white,” and so forth.

Security

In the natural state of human existence, “security” might involve finding natural shelter to protect oneself from a dreadful death, or, at higher levels, it could involve being armed, establishing oneself on high ground, and similar measures, which provided varying degrees of relative security for small communities. However, as humans moved beyond this natural state, other concepts of security began to emerge.

The meaning of “territory,” which is closely associated with “security,” has manifested in various ways depending on the opportunities provided by nature and history. At times, extending territory was seen as equivalent to securing one’s realm, with conquest and annexation of fertile lands being a means of expanding one’s domain. At other times, as illustrated by the myth of “Jamshed’s three expansions of the world,” we encounter a different kind of “world-expansion” with more complex meanings. This myth, when studied alongside Neolithic research, suggests the expansion of agrarian life into new territories.

As mentioned earlier, from around the 5th millennium BCE, with the advent of stable agriculture, large vessels for storing cultivated grains, along with domesticated animals and decorated pottery, began to spread gradually from an area likely centered around the Iranian plateau (Ray) or its western and northwestern regions. This expansion, step by step and settlement by settlement, established new villages and reached distant lands. Archaeological evidence suggests that this rapid proliferation of agricultural settlements occurred in this manner.

This migration and proliferation of early settlements was one method of controlling population in agricultural societies, where, in the absence of the wheel and transportation means, population growth could become problematic. Before this period, population control was managed through other means, such as child sacrifice and infanticide, all performed as part of sacrificial rituals.

The adoption of this new solution, involving the establishment of new settlements by a portion of the population, marks the arrival of a new phase and the emergence of a different worldview. This worldview was also propagated through migrations. As noted in previous discussions, this new way of life prohibited sacrificial rituals, condemned the plundering of neighboring tribes’ livestock, and valued the cultivation of new lands.

At the same time, this invitation reflects an awareness of the dangers of remaining isolated and insular (a “greenhouse” existence) for small settled communities, which may have stemmed from fears of repeating the failures experienced by previous agricultural societies. In practice, inviting others to settle was crucial for the survival of this way of life.

Small, settled communities were highly vulnerable to attacks from nomadic invaders. Even later, when settled agriculture evolved into the construction of large cities and the establishment of states with organized governance and powerful military forces to defend national borders, the primary and persistent threat to Iran’s borders—often resulting in complete occupation—came from these non-settled tribes. These tribes, driven by population growth, famine, or the desire to plunder wealthy cities, would descend from the vast northern pastures or the deserts of the peninsula into the plateau.

In reality, the expansion of this idea’s boundaries set the parameters for national security for millennia. The promotion of settled life experiences and new knowledge related to cultivation and domestication established a form of stability and relative security. The results of this shared experience fostered a kind of mutual understanding, alignment, and the development of shared beliefs and rituals.

What is certain is that the expansion and widespread adoption of techniques for accumulation, synergistic capacity, self-sufficiency, the growth of knowledge and experience, road construction, tool-making, control of water resources and wastewater, and the ability to communicate with others, as well as the development of agricultural rituals and the establishment of permanent settlements, contributed significantly to greater security.

The spread and proximity of settlements, to some extent, created a buffer against certain risks of crop loss upon which life depended. For example, archaeological research indicates that in the northern regions of the Khuzestan plain, prior to the formation of powerful cities, small settlements existed in close proximity to one another, forming an interconnected network with a division of labor among the various villages. 6

One of the factors that contributed to the proximity of cities and the reduction of conflicts among civilizations within the plateau was the presence and abundance of essential goods 7 in the neighboring regions. This availability facilitated trade and distributed power among the cities in a relatively balanced manner. This potential encouraged urban solidarity and reduced aggressive tendencies. The presence of these resources, combined with knowledge of preservation, storage, and innovative methods for intra-regional exchanges, required the development of a complex network supported by infrastructure, including roads and legislation.

Even today, what are referred to as strategic goods play a decisive role in the power dynamics and stability of civilizations, and they are fundamental requirements for the continuity of civil life and the settlement of human societies. These goods include various natural products, and access to their resources can either motivate unity and alliance for the exchange of goods and the establishment of security for all, or conversely, provoke constant conflicts, invasions, and wars between regions that lack these resources and those that possess them. The struggle over food has been one of the oldest forms of conflict among human groups.

Nomadic and invading tribes would descend upon other lands in search of grazing grounds for their livestock, plundering settlements along the way. Among the most fundamental necessities for survival are sources of fresh water. Grains and legumes, as abundant food sources, have held particular importance. Fuel is another essential need, which has gained strategic dimensions in modern industrial societies. Access to wood was crucial for mastering fire and developing furnace techniques in earlier periods.

Evidence indicates that bitumen, naturally occurring as overflow in areas with underground petroleum deposits, was used for insulation. During the Achaemenid era, petroleum (from the Old Persian root naphtha) was known, and the oldest identified oil well dates back to the reign of Darius I. 8

Similarly, other materials such as fibers (like linen, wool, cotton, silk, etc.) for making textiles and clothing were essential. Fundamental commodities also included metals, particularly iron and steel, as well as colored metals. Oil and salt were also vital resources for any civilization. In ancient times, salt was a valuable commodity not easily obtained everywhere and was abundantly available in certain regions of Iran. 9

Access to, identification, and cultivation of medicinal and spice plants were significant sources of food with important medicinal aspects, playing a vital role. 10 For example, one of the major sources of the immense wealth of the Ismailis of Iran (Hashshashin) came from collecting and cultivating medicinal plants and trading them as far as North Africa.

We are familiar with the commercial value of spices and the Hundred Years’ War, as well as the competition between the Spanish and Portuguese for the monopoly on importing them to Europe. Building materials were also crucial commodities that were not available in all regions. For example, the sandy deserts of the Arabian Peninsula lacked suitable clay for making bricks. Even up to modern times, inhabitants of the southern Gulf would acquire clay from the coasts of Iran through various means. Similarly, in some European regions, such as Flanders, stone was transported from distant places to prevent encroachment by the sea.

In the Iranian plateau, during the period in question, the distribution of these strategic commodities was such that they could only be accessed through the exchange between cities located in different regions.

As we can see, even today, in the absence or scarcity of any of these commodities, civilizations are compelled to either struggle to acquire them or seek influence in regions that possess the necessary resources.

Tolerance

Each civilization ensured its security through its own unique methods—either by homogenizing ethnic diversity within its territory or by equipping its military and establishing large garrisons in various locations. 11

In the Iranian plateau, located at the heart of the world with significant biodiversity and climatic diversity, and historically home to various peoples, one of the facets of security that was practiced and learned through both natural and cultural means was tolerance towards others. This concept can be recognized only through comparative analysis in the ancient world.

Within the Iranian plateau, especially in the western part, it appears that in the third and fourth millennia BCE, a certain balance was established between settled agriculture and pastoral nomadism.

Evidence suggests that there were regular exchanges between rural communities and small nomadic groups, with one party trading industrial products and the other providing hides, wool, and raw minerals. These constant interactions between communities with differing structures, which disrupted a homogeneous world, contributed to the richness of the legal system for regulating rules, establishing measures for trade, and forming treaties in early societies.

At the same time, these interactions nurtured an understanding of the potential benefits of tolerance towards others, emphasizing the need for mutual agreement and adherence to rules and order that benefited both parties. This is different from the awareness in other civilizations, which could rely on force to obtain what they wanted, a practice they had exercised over long periods.

Evidence of tolerance in diverse interactions can also be observed in the eastern part of the plateau. For instance, at the Burnt City, a variety of burial practices are found simultaneously in the city’s cemetery. Archaeologists interpret this diversity not as indicative of different social classes but as reflecting the presence of various customs and rituals among heterogeneous ethnic groups living side by side. Some of these burial practices at the Burnt City, as archaeological findings suggest, likely pertain to groups from southern Tajikistan who had migrated to the prosperous region of Sistan. 12

Today, linguistic studies reveal specific instances of ethnic migrations in Iran. For example, the language spoken by the people of Balochistan is related to the languages of northwestern Iran, particularly Tati. The history of Iranian peoples, their migrations, and connections remains shrouded in some degree of uncertainty. The ancient ties of these people cast a wide shadow over their early separation.

This issue is not unique to the Burnt City. Archaeological research confirms that the inhabitants of the Zagros foothills were ethnically diverse. Although they had internal conflicts, they ultimately united to resist the continuous invasions by Mesopotamian states. This alliance eventually led to the establishment of a central power in Elam, which was structured as a hierarchy of independent rulers under the aegis of a central authority that governed the region.

Thus, prior to what we recognize as the Renaissance and the establishment of the Persian Empire, a wealth of valuable and diverse methods for organizing varied societies had been tested through exchange, conflict, and cooperation. Despite all its diversities, the overarching spirit of this decisive period is characterized by the essence of “creation” or “generativity.”

Generativity

In transitioning from mythological culture, the concept of pregnancy evolved and acquired a material and existential meaning. (As seen in mythological symbolism, the celestial depiction of the moon was used to represent the transformation of the human body from the embryonic state to full development, and the journey from birth to death.)

The results of the transformations that followed the agrarian way of life highlighted the reverence for the natural generative force and the essence of life (Yin). It is evident that not only were various manifestations of natural generative forces venerated, but the entire cosmos was also sanctified as the womb of the world, and the norms of existence were esteemed. Additionally, from the ancient archetypes and early totems, generative dualities gradually emerged.

The fundamental concept of generativity and its maternal spirit, as embodied in the word “Saina” — or in its later form, “Simurgh” — gradually took shape and was disseminated through the rituals of the Yasna and the ceremonial Sina across the land, associated with the new agrarian culture. Within these rituals, a fresh understanding of cosmic order and human alignment with the spirit of existence (Arta and Ashavihisht) was developed among the people influenced by this cultural domain. The fruits of this worldview eventually permeated the epic texts of Iran, from the Yashts to the poetry of Ferdowsi and Attar and the lyrical verses, each time stepping into a new and more complex phase within its context. Thus, in Iranian epic literature, the motif of the Simurgh reflects significant aspects of divine awareness within this culture.

In this culture, the human-hero is nurtured by the “Saina” (Simurgh), from whose life-essence and immortality the human derives vitality. This essence is a flowing blood in every human being, imbuing them with divine grace. Thus, the human being, like the Simurgh, is destined for growth. The Simurgh is both luminous in the sky and colorful on the earth. In Persian literature, a section of the language of birds (Manṭiq al-ṭayr) explores this concept.

In this idea, the human-hero is “the fire of the seed” rather than “the water of the seed” (a meaning that Korban refers to as “the luminous human”). With the change of his life, the spirit and body are transformed into the earthly form, not through a separate creation. He does not descend into the world due to original sin but comes into existence with the qualities of rulership and with the will to engage in a battle for aiding Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda). The sound of the bell is the call of his heavenly body in the world (in the story of Kayumars, metals are the sediment of the heavenly body of man).

Similarly, in the process of creating pottery, the blending of water and clay, and the force of wind and fire (the four sacred elements or the four main elements of the world), imbues the vessel with life. The pottery, in its shape and capacity to hold, as well as in its components (clay and water), is feminine. The analogy of the human physical life cycle to the creation of pottery is one of the rich motifs in Persian literature, whose conceptual and metaphorical capacity has evolved over a long historical period, reaching its peak in Omar Khayyam’s quatrains.

Here, it is important to emphasize that our concept of “femininity” differs from the contemporary notion of “matriarchy” as understood by modern historians. 13 The manifestation of this maternal concept is not about the rule of women but is related to humanity’s understanding of fertility, productivity, and receptivity. This archetype is rooted in the essence of the earth and its rich, beautiful, and joyful nature as perceived by early agrarians. In the thoughts of these early cultivators, the earth did not appear with a lowly nature (Deni, related to “world” in ancient culture).

In this agrarian worldview, the meanings of the earth’s receptivity (Spenta Armaiti) and the fertility of water (Ardvī Sūrā Anāhitā) were so highly valued that they were conceptualized in the forms of goddesses.

With the dawn of the agricultural culture, human understanding of the concepts of fertility, productivity, and receptivity evolved, and the concept of femininity gained a significance that was rooted in the natural world and its bountiful, beautiful, and joyous essence as perceived by the farmer. In this new context, the role of women in transmitting culture through storytelling, songs, weaving, creating patterns, preparing food, setting tables, and lighting fires held a special place.

Nomadic awareness / Agricultural awareness

The relationship between humans and their lived experiences, and their engagement with nature and the surrounding world, emerges within the realm of words. It is within words that the “human world” and the cosmos acquire specific meaning, becoming tangible, existent, and comparable. If we view the major transformation of settled life as an awareness arising from a break with the illusory world of the past, should we attribute this newfound alignment and the emergence of new and shared understandings of concepts to the spread of the language of warriors and the dominance of the conquerors’ ideas? Or should we accept the view of researchers like Colin Renfrew 14, who suggest: “Language spread not through the valor of warriors, but by the plow of farmers”?

Language families based on agricultural origins (Nostratics) can be a valuable resource for understanding this phenomenon. It should be noted that many of the thousands of human languages, which were once isolated and unable to communicate with each other, gradually faded from the history of thought, becoming very weak or disappearing entirely. Nostratics languages, which include most of the historically and currently used languages today, emerged from a logic and essence related to settled life, which is distinct from the logic and world of nomadism and movement.

Thus, we observe that the poetic nature of humans, which is a shared trait, has developed both a natural and a historical dimension, following various and diverse paths. In analyzing the linguistic or literary heritage of different cultures, it is often the case that natural languages tend more towards understanding metaphorical concepts, while historical languages are equipped with a figurative expression. That is, in the process of cognitive development, natural languages incline towards creating complex metaphors and think through inventive conceptual frameworks that evoke one another, whereas the growth of historical languages is more pronounced in the domain of simile and example. In historical languages, comprehensibility and simplicity in syntax and the ability to convey precise concepts are central, and the continuous emphasis on “similarity” reinforces the foundations of logic and argumentation within the language.

Thus, each language generates its own specific keywords depending on its cognitive capacities. For example, among the keywords in the Iranian language family (one of the largest branches of the Nostratic languages) are the words “drita” and “païri.” For a farmer whose experience of life was translated into mental concepts through this language, the concept of “land” was the domain of existence, the place where the action of “drita” (to cleave) occurred; land that was split, carved, and separated from the shapeless natural whole by his efforts. This piece of land, after being shaped and domesticated by him, became imbued with a subtle essence, and he named it “païri” to signify the spirit that had become manifest within it.

“Païri” is the first part of the word “païri dāze,” or an embodiment of the world from which the concept of “paradise” emerged. This paradise is praiseworthy and commendable (Yashts 15), because it is known, transforming the beginningless, endless, and unknown existence into an orderly system within the framework of wisdom (khrā + rta or farr + rta).

For example, it is worth noting that the word “خِرَد” (khirad) in Iranian languages does not directly translate to “عقل” (aql) in the context of desert-dwelling Arab languages. The term “عقل” (aql) is etymologically related to “عقال” (iqal), which means “camel’s knee strap.” This suggests that, as a result of their lifestyle, an animal’s familiar body part, which serves as a support for its grounding on the earth, is metaphorically used to signify a concept related to one’s point of reliance or the power of individual judgment.

The comparison with the Arabic language is significant because it might be the most prominent non-Nostratic language in the contemporary world. Apart from loanwords from Persian, Syriac, and Greek into Arabic, examining pre-Islamic Arabic can highlight differences in the intrinsic structures and vocabulary of the languages, revealing two distinct lived experiences and ideas. 16

Intellectual legacies of foundational cultures, each in accordance with their climate and everyday experiences, gradually took shape. Each of these cultures presented its own narrative about the creation of the world and the genesis of humanity.

Based on daily life in agrarian experience, rituals and narratives were developed that shaped stories about human birth, destiny, and death, as well as the workings of the world. In this settled agricultural culture, the turbulence of life gradually shifted from being an unwelcome and uncontrollable force to a more manageable and comprehensible experience. The initial perception of humanity as a being cast into existence evolved into one where human agency and the ability to shape one’s own fate became more prominent. In contrast to the sense of disorientation in existence, the story of the fall and the interpretation of the world as a consequence of original sin were developed in nomadic cultures.

As previously noted, in the Gathas, agriculture was considered a sacred act and was a source of joy. Early scholars, including Barthold and Christensen, have referred to it as the language and literature emerging from the foundational agrarian culture of early urban societies. Particularly, the most significant ancient portions and fragments relate to the era of mythical figures such as Kayomars, Hoshang, Tahmuras, Jamshid, and Fereydun.

The story of Kayomars recounts the creation of the first human. His mythical aspects are embedded in his name; “Gaeomarthno” means “the immortal being who is reborn” (a description derived from the agricultural experience and the process of plant regeneration from seeds). This aspect of agrarian mythology, which interprets creation through a plant-like metaphor, is more prominent in earlier sources. For example, in the Yashts, the story of Kayomars describes how his seed mingled with Spandarmad, the divine spirit of the earth, and remained in the earth for forty years. Subsequently, the figures of Mashye and Mashyane emerged as a branch of this seed. These first human couple were so similar that their bodies were fused at the waist, making it impossible to distinguish between male and female. Among them was the divine glory (khvaraena), and a “spiritual” soul entered into them. They then became fully human and gained the “power of movement.” (According to Christensen, the continuation of the story has the flavor of later Zoroastrian theology.)

Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranian epic literature, has a name that is often analyzed for its etymological roots. According to one interpretation, the name “Rostam” may derive from the Old Persian or Avestan term “Rao Takhma,” meaning “seed of light” or “body endowed with divine radiance.” This interpretation suggests that Rostam represents a being imbued with divine energy or “farr,” which is associated with enlightenment and immortality.

In this conceptual framework, the notion of farr (فرّه), or divine glory, is considered an inherent force or energy within an individual. This divine energy propels the person towards growth and flourishing, much like a plant’s growth towards light. The essence of farr embodies the drive for enlightenment, vitality, and everlasting glory.

Christian provides the etymology of the Middle Persian word “Giyomard”, with its phonetic form gaya-ma-ratah and its active form gayomarata, explaining that “rate” represents the cycle of cosmic order. Thus, this name and story offer a concise depiction of the essence and existence of the fourfold nature of human beings (body, soul, spirit, and divine glory) within this culture. Specifically:

• Body (a plant resulting from blending with Spandarmad—Earth—and emerging as a rhubarb branch),

• Soul (the divine essence of the world),

• Spirit (harmony with cosmic order),

• Divine glory (the driving force of movement).

Here, “urvan” (soul) harmonizes and resonates with “Arta” (order) and becomes eternal. Its renewability is akin to the continuation of plant life within its seed.

The name “Rostam”, the Iranian world-hero, in epic texts, according to one etymology, is a transformed version of “Rao Takhma”, meaning “seed of light”, or a body that, through its divine or “farrah” power, moves towards light and eternity.

In this form of awareness, “farrah” or “noble growth”, which exists within each individual, is not only in the body but also a quality and force that resides between the body, soul, and spirit. This “noble growth”, arising from “farrah”, has a desire for growth and flourishing similar to a plant moving towards light (the prefix “far” or “par” in all its uses, such as in “farrah” and “culture”, signifies this growth force). Moreover, in this concept, “far” is free from disease or harm, as it is a chosen seed. The proliferation of this chosen essence (the hero or champion) leads to the accumulation of “farrah” for expanding and improving the world (in contrast to ideas that viewed human existence as a seed of evil and condemned its proliferation).

Thus, the existential concept of humanity is conceptually linked with the new experiences of settled life and agriculture, shaping its ultimate purpose and destiny.

In the experience of agricultural life 17 and in breaking away from the previous natural state, the formation of communal bonds was based on new relationships that could establish a shared responsibility among all. Working the land alone, without relying on an idea that gave meaning, could not transform the hard nature of the earth into a refined spirit. This idea was the continuous effort as a struggle to improve and enhance the world. This new awareness, which could only survive through synergy and the expansion of shared experience, inevitably had to extend beyond the confines of tribe and clan.

On the other hand, relying on mythology and predetermined fate in this way of life was a dangerous form of passivity. Changes in the climate of the Iranian plateau and the threat posed by prolonged periods of drought contributed to this shift. The result was the gradual formation of a type of mutual understanding about work and effort for future generations, which created a shared horizon in the individual and collective spirit of the Iranians. This idea, which bound the endless and beginningless time, opened up the possibility for a new perspective, namely “Dāna” (religion), or inner vision (conscience); the concept of conscience opened a new dimension within the human existence, providing it with an internal aspect and new significance. This system replaced mythological beliefs and the tribal-cum-ethnic regulatory system, which were largely based on blood rituals, and transmitted shared responsibilities through the establishment of rituals, thus creating a connection between the individual and the community.

Keyumars in the Yashas is the first human, created from a fiery seed. He is formed with equal length and width (square). He is recognized not by being male or female but by the attribute of kingship. From the residue of his heavenly body, the seven metals emerge. (In some rituals, the sound of metals is still seen as the emissary of the heavenly body of man. The influence of this idea can be seen in Christianity in the sound of church bells and in traditional Iranian rituals where a bell is rung by the mentor before the hero.)

The story of Keyumars, like other narratives in the Iranian intellectual heritage, has evolved over the centuries with changing awareness and has been adapted to the understanding of new eras. In the latest versions of the Iranian epic, such as Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, Keyumars is emphasized as the “first king.” (In later Pahlavi and then Islamic texts, his title is “Golshah.”) However, traces of older narratives of Keyumars as the first human still remain (including the account that he lived alone in the mountains for thirty years). His role as the founder of civilization, the initiator of kingship, and the establisher of urban systems, and his introduction of new culture in food and clothing among humans, along with his association with metals, reflect a public awareness of the historical eras that have passed.

In the world of the Iranian farmer, the functioning of the cosmos was explained through concepts such as the Amesha Spentas. Each Amesha Spenta had a specific name, embodying a particular quality, and appeared as a personified figure that could be experienced in daily life. These seven names, attributes, manifestations (and times) are as follows:

Ahura Mazda — the Wisdom Creator — Humanity

Vohu Mana — Good Thought — Sun — Bahman

Asha Vahishta — Truth and Cosmic Order — Sky — Ordibehesht

Khshathra Vairya — Divine Power of Good Rule — Metal — Shahrivar

Spenta Armaiti — Everlasting Divine Devotion — Earth — Esfand

Haurvatat — Completeness and Abundance — Water — Khordad

Ameretat — Immortality and Eternal Life — Plant — Mordad

Certainly, these rituals were initially practices directly connected to lived experience; they included:

• Work Rituals: Rituals associated with agricultural and other forms of labor.

• Rituals of Purification: Practices related to the sanctification of water and earth.

• Rituals of Irrigation: Rituals for clearing and preparing the land for cultivation.

• Rituals of Planting, Tending, and Harvesting: Ceremonies connected to the various stages of crop production.

• Rituals of Fire Maintenance and Worship: Practices involving the lighting and honoring of fire.

These rituals were deeply rooted in the practical and spiritual aspects of everyday life.

In the Iranian agrarian worldview, the nature and function of the cosmos were explained through concepts like the Amesha Spentas (Holy Immortals), which described the characteristics and operations of existence. The Amesha Spentas, or the Immortal Holy Ones, were considered as eternal benefactors and sources of prosperity. In the Minok, the seven Amesha Spentas were seen as symbols and manifestations of Ahura Mazda, and in the Gathas, they were regarded as forces that sustain and preserve the order of the world. Each Amesha Spenta had both celestial and earthly names, symbols, and representations; they were descriptions of creation and the transmission of cosmic wisdom to human awareness.

Each Amesha Spenta had a symbolic form in tangible, material phenomena, which was evident in their names; each had a name reflecting its essence, a manifestation or attribute, and an embodied form experienced in daily life. For example, the first Amesha Spenta is Ahura Mazda, whose manifestation is wisdom, and whose embodiment is humanity. The name of each Amesha Spenta was also associated with one of the months of the year, thereby linking time with abstract and fundamental meanings in agrarian life.

In this system, humanity was seen as the “center of the world” within the “sphere of the world,” where manifestations had both symbolic meanings and tangible, material existence, making them perceptible and relatable.

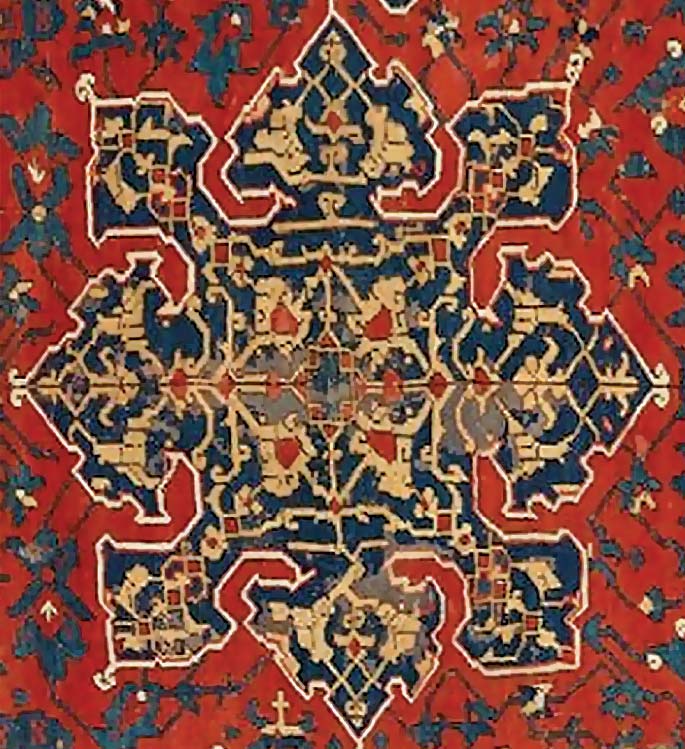

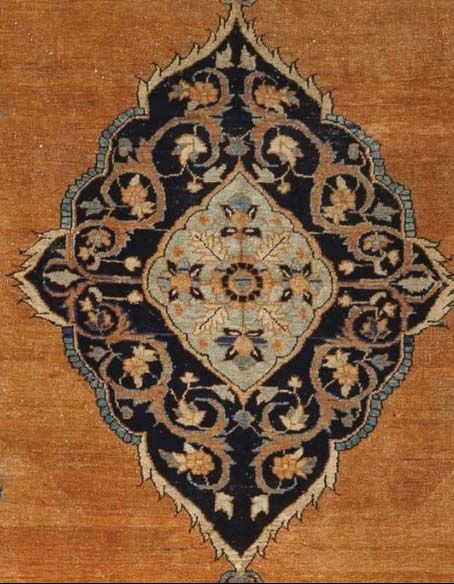

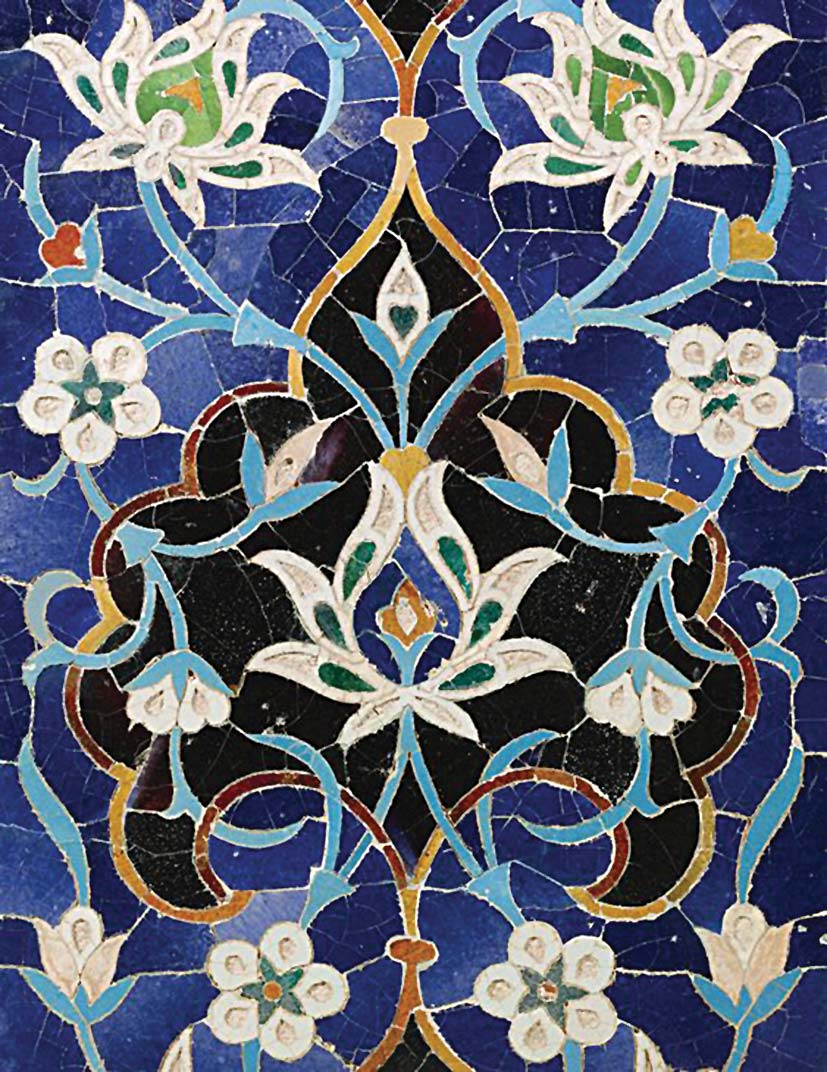

The system of designs and motifs in Iranian ceramics, tile work, and especially in handwoven textiles—due to various reasons including the weaver’s reliance on the transfer of memory of patterns—remains relatively unchanged and resistant to modification. This organization of motifs often resembles a garden or a series of handcrafted pieces surrounded by a “border” that separates it from the world or “natural realm,” with a central element or “toranj” serving as the core and life-giving essence. This central closed form is the starting point for the growth of vines, or what is now known as “arabesque,” which spreads across the surface with branches, leaves, flowers, and seeds, or what is referred to as “khatayi.”

Concept and representation

As briefly mentioned in the previous discussion, one of the images derived from the progression of consciousness and perfection in Iranian thought is that of a mighty tree whose roots are embedded in the earth. Its source of nourishment comes from the “būn-dādah” (primordial roots) 18, and its essence flows through the twisted trunk of time. The fruit of this tree is the blossoming of seeds of knowledge in the light of the sky.

In the historical treatises on Iranian music, as well as in the oral traditions that have come down to us—including the works of Abd al-Qadir Maraghi and the treatises of Safi al-Din Urmawi in the Muntaẓamiyyah school—there is a consistent description of the construction of musical cycles through the triadic relationship of “earth, time, and sky.”

In the system of Iranian patterns and motifs, including textiles, which for various reasons (such as the weaver’s adherence to transferring the memory of the design) are not easily altered or transformed, the arrangement of motifs resembles a garden—or handwoven pieces—that features a perimeter or “border” separating it from the world, or “natural realm.” At its center lies the “termeh” or “center,” serving as the core and fertile essence. This enclosed central form is the origin of the stem’s movement, or what is now called “Islamic,” which expands across the surface with branches and leaves, and its produce and seeds, referred to as “Khatay.”

These underlying themes, whose origins can be traced back to images from millennia ago, have evolved and transformed into countless forms and subtleties, yet their function remains a continuation of an ancient logic, some of which we find in the Bundahishn. In this idea, the world is pregnant with new manifestations, hidden in the nourishment of roots, and the essence of the “termeh.”

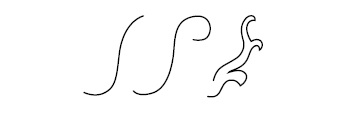

These three underlying themes, along with their corresponding movements, are evident in Iranian works across a range of artifacts—from pottery and bronze to textiles, jewelry, plasterwork, and sculpture, as well as in the designs and motifs of later periods and the cyclical patterns of melodies.

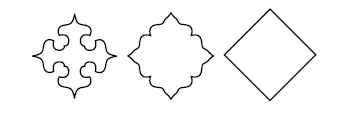

A closed form that appears in various shapes:

A movement with great variety based on this rhythm:

Another movement, despite its infinite expansion and proliferation, has a rhythmic basis as follows:

The motif of the plant stem growing from the core of the toranj, twisting in the sky, and bearing fresh flowers and seeds is one of the most enduring symbols in Iranian culture.

Footnotes:

- As mentioned previously, in ancient Iranian culture, which spans several millennia, this period is seen as the time of the first fertility and creation, culminating in the renewal of the Persian (Achaemenid) era. This corresponds temporally with the first creation in Greek culture.

- Gordon Childe’s theory regarding the Golden Rectangle, in relation to the Fertile Crescent theory, presents a different idea concerning the emergence of early civilizations. For further reading, see: Daniel, Glen (1984). Early Civilizations and Their Archaeological Origins. Translated by Haideh Moayeri, Tehran: Institute for Cultural Studies and Research.

- A sacred place functions as a center or a focal point to which one returns (such as the Hindu pilgrimage to the banks of the Ganges, or Muslims performing the Tawaf around the Kaaba). The Sanskrit word Paraya means “surrounding” (to circle around something), and in Old Persian, it means “to encircle.” The prefix of this word evolved in Middle Persian into “Paradise” or a garden. This Persian loanword retained its meaning of a sacred place or paradise in Greek, eventually entering Latin as “paradise” and then becoming “Firdaws” in Arabic. A sacred place is always a place of “beginning” and “end.” It is a place around which people gather in consensus. Over time, the center in human settlements may no longer possess this sacred quality and simply serves as a focal point. Cities then become sites for major gatherings that do not necessarily hold sacred meaning, such as Roman stadiums or Persepolis for festivals. Changes in centers throughout different eras correspond to shifts in awareness, such as observatories in historical periods or fashion centers in contemporary societies.

A sacred place is also a site associated with the meaning of a sanctuary or altar. In Christian theology, although the Son (the Son of God) was the ultimate sacrifice for the salvation of human souls, places of martyrdom and burial of saints still convey the concept of a sacred place. For instance, St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City (from the time of Constantine onward, pagan Roman altars were transformed into sites for the burial of saints and Christian martyrs).

In contexts where the concept of the city is related to land and political units, the center evolves into a hub for the administration of the city and territory, assuming various functions beyond just evoking the notion of a sacred place. For instance, places like Chogha Zanbil, which included water purification facilities and sections for controlling the surrounding city, exemplify this transformation. The ziggurats originally were indeed expressions of the idea of constructing a sacred place, but over time, in some cities, they took on additional functions and, in certain regions, continued to retain their sacred status (such as the Egyptian pyramids). - Similarly, the four three-thousand-year periods of Zoroastrianism also represent this notion of measuring the boundless passage of time and embody the four seasons.

- The term “Silk Road” for this ancient trade route is a relatively recent designation, coined in 1877 by a German scholar named Ferdinand von Richthofen. Modern interpretations of the concept of “trade” can sometimes create misconceptions when understanding the connections and exchanges in the ancient world.

- For further reading, refer to: Comprehensive History of Iran, Volume 1 (2014). Tehran: Encyclopaedia of the Islamic World Foundation.

- Some of the goods that have changed in history and whose value and importance have varied include: water, grains, iron, colored metals, fibers, proteins (and oils), fuel, sugar, salt, fodder, and medicinal substances.

- The Chinese have used coal since ancient times, a substance that, despite its abundant presence in Europe, was unknown to Europeans until the 17th century.

- Just as the Roman army was paid in salt, and this term’s root persists in some European languages in the word for salary, in some regions of China, obtaining salt required transporting it from very distant locations. This changed during the reign of Emperor “Tan,” who developed a method of obtaining salt through ground drilling, a technique similar to modern oil drilling methods.

- In Greek medicine, consuming a small amount of spices was considered medicinal, while excessive use was regarded as poisonous.

- Ideas that attempt to explain Iranian civilization based on Aryan race and theorize Iranian history through the military dominance of Aryans over others bear a strong resemblance to the ideology behind the racial superiority theories of some European peoples, such as the Celts and Germans, over others. These ideas draw parallels between the atrocities committed in contemporary North and South America and other European colonies in Africa and Asia, based on the supposed overall superiority of the white race, with ancient historical narratives. Regarding our own history, we can at least seriously question the importance and centrality of such ideas. Especially given that scientific research to date shows that 98% of the genome of people from the Iranian plateau is inherited from mitochondrial Y (mother) and has a lineage spanning 12,000 years.

- For further reading, refer to: Comprehensive History of Iran, Volume 1 (2014). Tehran: The Foundation for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia.

- In modern times, the creation of this term involved the use of Greek verb-forming suffixes such as “kratos” and “archon,” which convey the characteristic of “rulership” (kratos). However, this application often carries a negative connotation and appears in various contemporary historical discourses, which are not our primary concern here.

- Colin Renfrew

- “Yazshan” or “Yazteh” means “praiseworthy.”

- In an essay titled “Persian or Arabic Language of Iran?” Zabih Behruz offers useful insights into these differences. For instance, he notes that the Arabic word for “politics,” “siyasat,” originates from “sasā,” meaning to tame a colt, and “sā’is,” meaning caretaker of animals. However, in Greek, the term is derived from “polis,” meaning city or settlement. Behruz goes on to say that comparing the roots of these two words will surprise the reader because taming a colt seems unrelated to a city. Yet, it can be conjectured that taming a colt in nomadic life might metaphorically relate to “urbanization” and “city governance,” which is the implied meaning of the Greek term.

And In comparing the Arabic root of the word “dawlah” (government or state), where “dawla” means “to change” or “to circulate,” with the Latin root of the word “status,” which means “standing” or “to stand,” it is evident that these two words are fundamentally opposed: one signifies movement and change, while the other signifies stability and standing still. Despite their divergent meanings, one might speculate that these terms reflect the essence of their respective cultures. In a nomadic desert lifestyle, where the basis of livelihood involves constant movement, the concept of “change” (dawlah) is central. In contrast, urban life relies on stability and “standing” (status). Thus, metaphorically, these words could be seen as conceptually related due to the differing foundations of desert and urban life.

17. A significant part of the difference in agricultural experience and the resulting philosophical thought between China and the Iranian plateau can be attributed to climatic conditions. Unlike the Iranian plateau, which frequently experienced droughts, China and its surrounding regions did not suffer from such recurring droughts. The oldest and most enduring agricultural fields in the world are found in East Asia, with rice and tea cultivation being prominent. Notably, in some regions of China’s cultural sphere, such as the Philippines, rice has been cultivated continuously for 12,000 years. On the other hand, the major rivers of China originate from the west and flow towards the east. The western regions of China, including the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, and parts of the Pamirs, are still the largest sources of fresh water on Earth. This generous and inexhaustible source, flowing from the heights to the lowlands, presents a different view of order, power, and governance—a hierarchical system of unknown and unnameable powers descending from above. The earthly manifestation of this order is reconstructed in forms such as Dao, the emperor, rulers, city officials, and the father of the family. This system is based on unquestioning obedience, akin to nature itself. Even in modern times, Mao Zedong, in his role as the savior and final historical leader of China, appeared once again as the great Khan, famously marching with peasants from west to east and symbolically immersing himself in the Yangtze River.

18. The concept of “Ben-dehesh” aligns with this meaning.

- For the etymology of Persian words, refer to: Bahrami, Ehsan (1990). Farhang-e Vazhgehā-ye Avesta. Edited by Fereydoun Janidi, Balkh Publishing, affiliated with the Neyshabur Foundation.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.