Iman Afsarian: I think after all the experiences our people and artists have gone through over the years, the issue of identity remains a central concern and a topic of debate. Perhaps it would be good to start our discussion from this point of view and your perspective, given that you have been painting in Iran for years and then in Germany.

Masoud Saadeddin: First, I would like to explain the issue of “identity.” Our confrontation with Western art was essentially an engagement with perspective. This perspective, which had been painstakingly developed over 300-400 years by many artists, was a detailed process that shaped the representation of space and even portraiture. You can see this confrontation in the works of Mohammad Zaman, and since then, there have been initial efforts to preserve our artistic framework while employing the rules of perspective. We see that the issue of identity is still relevant even when we have social authority, and it becomes more acute when we lose this authority, giving rise to a kind of fundamentalism. This issue persists today, and none of us have been able to definitively solve it. I believe we need to completely move beyond this story. Everyone should accept that they have their own mindset and worldview, and this mindset is equivalent to mindsets everywhere else in the world, neither inferior nor superior. Although we have little self-confidence and are in a position of weakness, if we accept this reality, the artist, as an individual, does not need to abandon their social and geographical position but can comfortably engage with their own mindset and act with confidence. In my view, the era of separating the past is over, and we should see this collection as a single unit with geographical and cultural characteristics that everyone automatically possesses and doesn’t need to work hard to acquire.

Afsarian: I doubt your idea that the solution is to move beyond the story of identity and focus on individualism. The problem is that we think an individual can work outside of a tradition and context. A clear example is yourself; although you have always been engaged with your individuality, the recent works you have exhibited have clearly formed within the context of contemporary German art. The question that has been around as long as individualism itself is how far can we be “individual”? How far can we be free? There are always contexts, whether it’s history, society, collective unconscious, or whatever you call it, that shape individuals. While it’s true that the question of identity led to a kind of fundamentalism, how do we answer the question of context and tradition? Can we start from zero, from nothing?

Saadeddin: One cannot start from nothing; the individual does not exist either. Individualism is a general concept where a person in a body tries to organize issues for themselves. Your point is entirely correct. We are interconnected; I do not deny identity and see it as a dependency on a cultural matter. I believe identity is to be connected to this life, to where one lives, and to the thoughts and issues of others and those who came before. My point was that we should not limit this circle to a geographical region; we should expand it. When you have read Kafka and seen Rembrandt’s paintings, these are also part of your identity and tradition. They were not there once, but now they are, and they fill our minds. We cannot escape them.

Manouchehr Safarzadeh: In today’s world, I see a problem that is not just Iranian but global; styles and groups as they existed in the past no longer exist. The artist stands in front of the world, informed about global culture, having seen, read, and interacted with it, and now must find themselves. Painting today is not a regional or local traditional issue; it is something individual and personal, a kind of sitting within oneself.

Saadeddin: The issue of identity, as Safar says, is a global issue. I think, due to many political and psychological matters, certain definitions have been exaggerated and are far from reality. For example, if we consider Mani’s paintings, they were influenced by the early “catacombs” and Greek art, then entered European book art, and from there, influenced our miniatures. Human life is short, and this two or three-thousand-year journey is not much. These comings and goings have created common issues. Thus, the distinctions are not as we think; we always emphasize differences.

Afsarian: I frame my question this way: my issue is language. We speak through language and cannot speak without it. Gombrich examines art history as a series of intra-linguistic discourses; in the language of painting, questions are posed, and each painter provides answers that have cracks, which the next painter opens and raises new questions. The issue of language and which language to speak is more fundamental than this. The question of identity arose after we faced problems choosing a language, becoming a secondary and parenthetical issue within the broader question of language.

Safarzadeh: I started with the same language as in our past paintings. For instance, there is no perspective in our past paintings, and it has a different essence than Western paintings.

Afsarian: Let me clarify my question; simpler and more tangible: imagine someone growing up to age 30 without learning any specific language accurately. From that point on, they want to become a poet. They forget the issue of identity. Thousands of languages are before them, from ancient Pahlavi to Sanskrit, Native American languages to English and German… which should they choose? What is the starting point? This situation is very similar to our art students who enter classes or universities at the age of 20 and want to become artists without knowing which language to start with. What I want to know is how you, who have been dealing with the language and its selection for years and reached a point in Germany where you decided to set aside the issue of identity, began at the zero point or void. Even at that moment, every line you draw, every figure you design, you have learned from someone or seen somewhere and are unconsciously involved in the issue of language and consequently the issue of identity.

Saadeddin: You are posing a problem that is really difficult to answer. There is always an initial point that indeed directs you, and no one can escape this story. Every artist in any part of the world and at any time has faced this issue.

Afsarian: I don’t think it was the same for Rembrandt in Amsterdam. He worked within the Baroque tradition, rooted in Renaissance painting of Northern and Southern Europe, tracing back to ancient Greece and Egypt. He drew from there, and such a question never arose for him. His task was to represent the human face and space with oil paint and brush on canvas, achieving maximum illusion and light effects. In this path, he had to compete fiercely.

Saadeddin: We do not personally create history. As Heidegger says, we are thrown into existence and then try to find our position and place. This is the origin of any movement, and there is no escape from it. In this sense, Rembrandt and I have both been thrown into existence and then connected to a point. The beauty of art lies in this: we connect to a point at the very beginning, and from there, stories diverge. It is like Darwin’s theory of species: something happens biologically, an accident beyond personal control. We always enter the story from the middle, unaware of the flow from the start. Later, when we realize, we are already part of the story, the questions and doubts begin. Now, amidst this turmoil, one must search and find oneself.

Afsarian: The main problem may be much more alive and tangible. What made you leave Iran? I don’t expect you to talk about the finer details of your life. I am more interested in your theoretical mindset to get a more general answer.

Saadeddin: How did my story begin? … When I entered the college, I had no idea about anything. All the Tolstoy I had read came from a place like Semnan. I had connections with nature. My grandfather’s house had pine trees, and my father was a train driver. I had brothers. There was a story; I had read Dostoevsky, Sadegh Hedayat, Chubak, and Hafez. In college, I immediately got involved in something. They taught me that I had to learn design and if I could depict the human form naturally, the issue was resolved, and that was the essence of art. Later, Mr. Momen said you had to find and understand gender too, and Mrs. Bahjat Sadr said you had to pay attention to feelings. In the library, every day, I eagerly and thirstily pored over the history of art, reading Brecht and Kafka…

All of this progressed together without any organization, meaning the main question still hadn’t been posed. Love had entered my mind, and I didn’t know why. It wasn’t even a question for me. At first, I thought I might become important or famous, or that I could express things no one else had been able to. But over time, questions gradually formed, and those initial questions must be remembered. For example, the first serious question for me was whether a painter can create a space that belongs only to himself. That’s why I went to Semnan and locked myself in a room for 2-3 months, drawing all my childhood memories in a notebook. I felt this could be a good starting point to organize my perception of images and seeing. I took patterns from the works of Al-Khas, Max Ernst, and others. These were expressionists who had a certain quality of Taoism in their work. This helped me draw my own mindset without great abilities. The way Al-Khas worked with us aimed to make us complete designers. Midway through, I doubted this approach. It seemed to me that the more sloppy and crooked a person’s work, the more feeling it had. I started working against his teachings, and without realizing it, I was organizing my mind about what I wanted and how to proceed. This coincided with our revolution. The events of the early revolution brought all of us out of our seclusion. The fervor of the revolution, before our mental frameworks formed, pushed us towards strongly external movements; saving society, saving Iran, and social and human issues engulfed us to the point that art took a backseat and became a tool for propaganda. I went to the front with Younis Asadi on the front lines, and that’s where our fundamental discussions began again. We quickly realized that the solution in art wasn’t to teach society and give moral lessons. When we returned, we formed a group of 4-5 people. Me, Mash Sefar, Bani Asadi, and Dabbiri concluded that we had to start painting from scratch.

We gathered once a week to discuss art. We felt our knowledge of art was very incomplete. We started studying the history of art, especially modernism. In our discussions, we concluded that we had to let go of group perspectives and focus on individuality. The importance of modernism for us was because of its emphasis on individuality, which we had come to understand. In this chaos, I went to Germany. The reason was clear: I realized I couldn’t find what I was looking for here. There was no one to give me these things, and we were struggling in an unclear situation. Scattered materials had been translated, all of which I read, but the information was incomplete and the stories disjointed.

Afsarian: Now, after all these years, can you clearly say what you were looking for?

Saadeddin: At that time, I knew I wouldn’t find what I wanted here, but I wasn’t clear on what I was looking for. I guessed that maybe in Europe, one might get closer to it. I planned to discover this issue for myself in 4-5 years and then return. At first, nothing there amazed me. I didn’t know what I was looking for, nor did I clearly see what existed. The more I looked, it was the same story of modernism I was familiar with from books, but now I was seeing the original versions. It took 43 years to see what was happening immediately. During these 3-4 years, my work was a continuation of my work in Semnan, but extremely expressionist. I painted these works with great enthusiasm. After a few years, I felt a kind of burnout from this type of work. I felt I was doing the same thing the expressionists had done before. To put it simply, with my raw mindset, I felt left behind. I thought, now that I’ve come to Europe, I’m still the same person and doing the same work!

Afsarian: So you were struggling with being new and avant-garde?

Saadeddin: Exactly. My issue was to go straight to the top. I thought you had to search and find the ultimate flow and connect yourself to that final point. These thoughts made me grow tired of expressionism, and also, because of its extroversion, it seemed like a self-narration. I felt like I was sitting and doing self-therapy. At the same time, the issue of identity arose. For the first time, I seriously faced the fact that I was an Iranian painter and had to show it. It was precisely at this time that I discovered European painters who worked in an expressionist style like mine. I discovered them after three years, just as I was abandoning this type of painting. Such supports emerged. On the other hand, the issue of identity was also present for me. Therefore, my problem was solved.

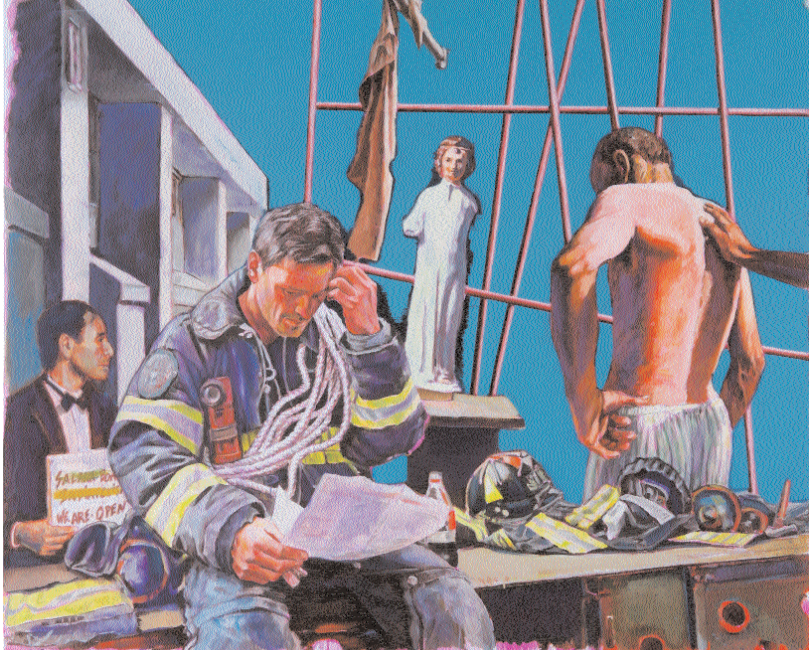

In 1987, I wrote some things for Hannibal al-Khas, which I later realized were close to postmodernist theories. I wrote that the linear evolution of art was over and now had to move laterally. Although I had reached this point intellectually, I wasn’t satisfied in practice, and this confusion about what to do continued. The reason is clear to me today: I was avant-garde within the framework of modernism, I hadn’t stepped out of that story and reached myself. In modernism, you have no choice but to cling to its end. My efforts in these years were a dead end. From 1994 to 1996, every day before leaving my studio, I would whitewash my work. It became clear to me that I couldn’t find anything and didn’t have the ability to achieve something within this framework. Later, I consoled myself that as a painter, I was a “medium,” and if I couldn’t achieve anything with all this effort, it meant painting itself couldn’t achieve anything and didn’t want to. Painting was dead, and it wasn’t a personal issue. These are all avant-garde thoughts, meaning you create an expectation that practically isn’t possible in your time. One day, I thought, you are a painter, and with all this love and involvement, why isn’t the “work” itself important to you? Just work. I was content, and no longer had the anxiety of art history. Without realizing it, the time had come to separate from this mindset. In the art we formulated, there was gradually no escape for painting except to free itself from this avant-garde narrative and attend to its own story. And to me, this personal story means the presence of something real from the outside world. I think what can be salvaging is the inclusion of something from reality that isn’t related to art at all, because as soon as you engage with artistic elements, the issue of composition, conciseness, and all the questions posed by modernism begin.

Afsarian: It seems to me that sometimes the path one takes can model the movement of a larger group of people; you were looking for something you saw incomplete and skewed examples of here. You had questions and knew you wouldn’t find answers here. So, you wanted to find the center of that flow. When you entered the center, you faced the issue of identity acutely. So, the question of identity wasn’t a secondary one; it was a real question that, when it arose, deeply engaged a person. This entire process, from your move from Semnan to Tehran and from Tehran to Germany, was an effort to join a global identity. And interestingly, up to this point, you were never really engaged with your Iranian identity and finally decided to pull yourself out of the avant-garde game, which I call global art. That dominant global hegemony promoted by central art institutions in New York, Paris, etc., which is not without value, usually works on specific, valuable works. It seems that at some point, you set aside the question of global identity, reduced the concern for display and show, and engaged in the act of painting itself.

Saadeddin: This perception is entirely correct. Anyway, when you are young, you want to become a great artist, and you equate that with participating in this global identity. You shouldn’t compare yourself with local artists; you have to surpass Picasso and Francis Bacon. This foolish mindset has been shared by many artists worldwide. It’s a human thing and also creates a certain spirit in a person. At one point, I realized that from a logical standpoint, it’s a very hypocritical endeavor. If you are clever, you can discover formulas, win awards, and possibly gain some fame for a few years, but that doesn’t mean you’ve done substantial work. I concluded that many things are beyond my control; I can only do my own work, and later, it is this collection that selects people.

Regarding identity, I believe that the past 300-400 years of our history have constantly pushed us to assert ourselves in front of the world and prove our worth, shaping and utilizing identity in this way. I think we need to let go of this kind of identity; it doesn’t help us and keeps our art mediocre. These issues engage our minds with problems that are not relevant to our work and force us to act not as individuals but as representatives of a general trend, like the representative of Iranian art going through fire and coming out.

I do not deny identity in its sense. I believe that every artist must find themselves in their work and consider the entire history of art as a tool. In this way, many of these questions are eliminated and left behind, and you return to the present time, to your own mindset, and you say to yourself that this mindset must be transformed into form, must become poetry.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.