An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

The upcoming lectures aim to draft an introduction to the “History of Art and Culture of Iran.” Therefore, as a first step, we will briefly examine the terms “art,” “history of art,” “culture,” and “Iran,” with the note that many of the points introduced here will be elaborated upon in subsequent lectures.

Art

Fundamental human questions about “humanity,” “existence,” and “time,” about their poetic nature, manifest in the form of the arts. Moreover, humanity names the world through this poetic nature. In historical societies, due to disruptions in consciousness, the meanings of names and words evolve, each word having a history that reflects the transformation of the consciousness of the people who speak that language. For example, the approximate equivalent of the word we now use for “art” in Aramaic and Syriac is “umanuta,” meaning “creating from nothing” (the Latin word “human” also derives from this root). The word “art” itself originates from the Greek word “arete,” which is etymologically related to the Avestan “arta” and Old Persian “arta,” all meaning the order of existence. The altered form of this word continues as the prefix “art” in words such as “article” and “artery,” signifying connection and order. However, the core meaning carried by the Greek “arete” was later transferred to the word “virtue,” gaining a more complex meaning in Machiavellian texts.

Therefore, the fundamental change from the Greek word “techne” to the Latin “ingenium” marks a shift in the history of consciousness and the entry into a new world. In the early Middle Ages, all forms of art were called “engine,” and artists were referred to as “engineers” (a word we now use for “engineering” with a different meaning). In this new context, art was understood as the order and norms surrounding the Logos, and the artist manifested this order in discovering proportions and sacred geometry. This underlying meaning gave Gothic period artists the capacity to continue projects for over two centuries. In the late Renaissance, the ongoing transformation in the understanding of the new concept of the subject (“Subjektum” of early Aristotelian church scholars) led to a subsequent disruption in consciousness. This time, the disruption from Plato’s “Hypokeimenon” appeared in artistic works, which some art historians regard as the beginning of modern art. In this period, a new concept “Beaux Arts” emerged, conveying the notion of “beautiful connection” or “beautiful order.” The transformation of the concept of “Beaux Arts” to “art” in the language of the later period, following two more disruptions in consciousness and a new understanding of the subject concept, became evident; first with the Cartesian subject (contemporaneous with Dutch Baroque painters like Rembrandt), and later with the new subject concept after German Idealism. Here, the art historian, in writing the history of European art, attributes this later meaning to the entire history of art—not just the history of European art, but of the world.

In Persian, the word “honar” (هنر) from the early languages of Avesta, Old Persian, Middle Persian (Pahlavi), and New Persian conveys a concept whose multi-layered historical meanings penetrate the spirit of Iranian culture. The usage of words like “fan” (فن) and “sana’at” (صناعت) from Arabic in New Persian did not achieve the breadth and depth of the meaning of “honar,” as they only pointed to one of its superficial layers. The word “honar” is composed of two parts: “ho” (هو) meaning absolute goodness and “nar” (نره) meaning capability, together meaning “good capability.” Ferdowsi, in explaining this word, says:

“Honar is humanity and righteousness / It is reduced and diminished by crookedness

How can there be honar without nobility? / Have you seen anyone noble without honar?”

This concept of “honar” has a deep relationship with the heroic thought in Iranian culture. Considering the meanings of the words, “honar” in Persian is closer to the modern German word “Kunst” than the English word “art.” The German word “Kunst,” which is used for art, is derived from the root “können,” meaning capability. This similarity may be due to the presence of heroic thought elements in ancient Germanic culture. The word “honar” in Persian, in terms of etymology, has transformed into the word “honor” in English, acquiring a different practical meaning. The relationship between “honar” and heroic thought in Iran is one of the topics that will be addressed in future lectures.

On History and Art History

The historical human is the possessor of eras, in that they establish a meaningful connection between their past, present, and future. The historical human, as a subject, interacts with the object of the past rather than seeking awareness within the past itself. Therefore, “being historical” does not mean merely “having a past.” After all, all people have a past, but many nations, when confronted with other civilizations, completely lose their connection with their past. Losing this historical dimension signifies the end of a civilization and its intellectual essence.

Regarding the current situation in Iran, although we establish a connection between our past, present, and future, the fabric of this relationship has unraveled.

In situations where a culture cannot explain its ancient awareness with new concepts, and cannot cast a new light on its traditional thinking, it inevitably acts unconsciously and out of habit. Such an existence might still have quality, and people might benefit from the technology and resources of their time, but it renders them incapable of producing thoughts and theories that explain their position. As a result, people merely repeat behaviors observed elsewhere. This form of existence can be seen in many contemporary societies.

However, “historical awareness” is not achieved with the idea that there is a “true history” capable of explaining all foundational cultures and civilizations of thought. The idea of a “true history” is naive and futile, placing us in a timeless and void situation. It is important to recognize that any theory will only be effective if it is measured against the historical materials and thoughts of that culture and subjected to criticism; in other words, referencing another’s awareness is merely a light we shine on our awareness.

Writing any “subject history,” such as the “history of theology,” the “history of philosophy,” the “history of literature,” and here, the “history of art,” in the modern age, inevitably relies on a theory. As mentioned, finding a general and universal theory is not possible, and each founding domain requires a separate theory. This theory must originate from the “absolute idea of awareness” within that culture. The diversity and multiplicity of historical awarenesses do not necessarily imply a counterpart for every land or nation. As we can see, developing a theory of art history in the European world became possible about the entirety of the civilization and the historical transformation of European thought.

For scholars and historians of Western thought, although the Greek-Roman period was an entry point into the European world, works such as Homer’s “Iliad” or Virgil’s “Aeneid” could not serve as the foundation for writing the history of art. This is because these works did not have a universal address in Europe and could not play a role in maintaining the historical spirit among all European nations. Instead, Christianity played a major role in resonating with the common spirit of Europeans. Due to the importance of the concept of incarnation in Christianity and the ritualistic use of visual arts in the public culture of Europeans, “visual arts” were emphasized and examined as a pivotal common concept for drafting the “history of art” in Europe. The history of music, poetry, and other cultural domains was compiled separately for more limited cultural areas.

Here, we should also consider another point: the role of shared festivals and rituals as the unconscious actions of the historical spirit among the general populace, which can create “synchrony” and “shared worlds” among nations, is of particular importance. Among European cultures, it was again these Christian rituals (such as the Mass) and religious festivals (like Christmas and Easter) that played the role of constructive elements of the “shared historical world.” Among Europeans, national festivals, in the form of commemorating revolutions or victories in wars, have a history of less than three centuries.

Regarding the role of Iconology in the history of European art

The first historians and theorists of European art, such as Wolfflin and Panofsky, placed Iconology at the foundation of art history theory. Panofsky, inheriting the philosophical ideals of German Idealism, structured his theory of art history around a “universal idea”. This universal idea elucidated the essence of European art in connection with the concept of Christian time (linear time) as the entry into historical periods.

Thus, the entrances to art history such as discussions on motifs, modules, structures, and the differentiation of works into decorative and fine arts were organized on this primary basis. Naturally, a foundation based on an Iconological approach cannot effectively explain the works of other cultures, and even in interpreting art in the modern Western context, this method lacks the necessary tools. Therefore, new approaches such as phenomenology, psychology, sociology of art, and other late methodologies have come to aid and have opened new thresholds.

Common theories in art history interpretation are firmly grounded on three layers: form, idea, and content. However, when interpreting the substance of an artwork, one must not only consider its form, style, and content (the aforementioned trilogy), but also delve into deeper layers that shape the specific existence of those works and their culture. These layers, which may even be unknown to the artist, are dependent on meanings and ideas that have developed in the history of civilization, influencing the political, poetic, religious, philosophical, and social inclinations of the artist. For example, one can recognize the Neoplatonic inclinations of Michelangelo behind his Catholic Christian identity, or understand the Iranian influences on Muslim Iranian architects like Iranshahr and Ashraqi, or observe Daoist thinking in various eras of Chinese artists’ works.

Each style is based on a form rooted in history and continues the tradition of its founder’s school. The motifs arise from the visibility of historical spirit; hence, foundations (motifs) do not emerge in a void.

The perspective of a nation, era, class, belief, etc., crystallizes within a work when reciprocal connections are established among the trilogy of “form, idea, and content”. This means that form is influenced by idea, and idea and content have such interrelations. This is the underlying force in a work that isn’t immediately apparent at first glance.

“Form,” as the embodiment of spiritual consciousness, materializes as a result of historical experience, derived from realities, emotions, experiences, and experiments. Understanding “idea” is facilitated through analysis, where reason, logic, and underlying hypotheses reside. “Idea” generates “style”. Therefore, artists attain “methods” (techniques) that facilitate the manifestation of ideas in their works.

For an interpreter of a work, explaining the dependencies of form and idea always leads towards content. Content appears as the apparent subject matter of the work, such as a story, myth, or sometimes a mundane narrative, yet it carries beliefs, expectations, and intuitive feelings.

Superficially, these three layers can be identified through tools apparent within the work itself. For instance, the first layer (“form”), could arise from the manner of lines, colors, space, sound, words, and movement. For interpreting the second layer (“idea”), symbols, signs, and the balance and symmetry created in historical styles can be utilized. In understanding the third layer (“content”), one can draw from sources, texts, myths, and stories. Undoubtedly, none of these layers can exist or manifest meaningfully in isolation.

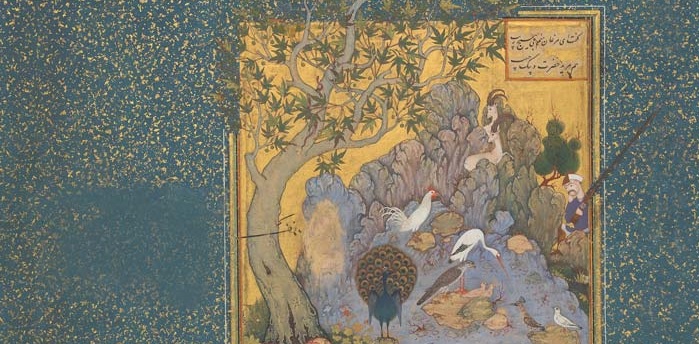

Beyond civilizations and intellectual domains established in human thought history, there exists a fourth layer. This deeper, more multifaceted layer is not confined or named; it is a concealed world hidden in the depths of the soul of any culture. It may manifest in a way each time, becoming apparent when work finds a common central core with that deep layer. For example, the role of Simorgh in the overall design of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque. This awareness, the awakening of historical intelligence in any nation, can manifest even in times of nature and intellectual decline. For instance, the priceless work of Ferdowsi at the beginning of the decline of Iran’s homeland, the art and wisdom of a thinker like Sohravardi, who illuminated the wisdom of kingship during the hardest times, or in the astonishing metaphors of the poet Hafez during the periods of turmoil.

Artwork is contemplatable from every angle, but when discussing “art history”, it is a subject that is investigable under the theme of modern age. “Art history” is a modern concept and only has meaning in relation to the awareness of this era. All contemplative perspectives, such as cosmic art, mythological, classical, heroic, etc., are shaped by discussing art history in relation to a theory (theory).

Until a “basic history” base for each territory does not find a relationship with its “lived history”, the historian cannot effectively comment on the history of others, or benefit from theories created in other cultures. Lived history is the place of “national formation” awareness, and written history is its “writing”. Awareness has become an internal and lived matter, and its explanation is not possible from the outside. Therefore, the coordinates of national awareness cannot be depicted from the outside. We can reflect on the achievements of European historiography as a beam on the angles of our awareness, but to formulate our history, we are inevitably bound to construct a system of concepts and principles that are compatible with our historical materials.

The apparatus of concepts and principles of modern European historiography pertains to the materials of European history itself. This historiography categorizes its prehistoric and mythological awareness under the general heading of the “Age of Magic” (Majīk). It then sees itself as inheriting a long period of achievements from realms beyond Europe. Some historians, like Will Durant, classify these external realms under the general heading of the “Orient,” a cradle of civilization. Following this, they recognize ancient Greco-Roman civilization as their origin. Based on a framework constructed from the concept of time and periodization, they define the “Middle Ages” as a period within “world history” and explain all other cultures about it (such as Islamic art and others).

This perspective emerged in European thought during the new era from the definition of the “Renaissance” or “Rebirth”. From the heart of the Renaissance, as a rupture in thought upon which the foundations of the new era are defined, a new understanding relative to the ancient era has taken shape.

The concept of “progress,” despite the ambiguity that exists in its historical and artistic context, is generally incompatible with the historical developments and art history of Iran. This is because it is a theory developed in relation to Christian chronology. Moreover, reliance on Orientalist theories represents another flawed approach, as Orientalism itself is one of the sciences of the new era, with its counterpart (Occidentalism) not evident in the knowledge of the inhabitants of the Orient.

Regarding Orientalism and its influences

Orientalism evolved out of the ongoing need for knowledge of conceptual history, and subsequently gave rise to other sciences such as ethnography, linguistics, national musicology, and other humanities. This knowledge positioned itself against the foreign, transforming into an ability to think critically. Western civilization, when confronted with non-Western cultures, classified them under various “logos”. Due to the ensuing actions and reactions, concepts and terminologies were created which have no precedent in our Iranian world today.

The result of applying these concepts and the valorizing view of folklore and ethnology, characteristic of Orientalism, has led to a misinterpretation culminating in a kind of imagined inversion. Thus, notions such as “remaining old,” “authenticity,” “exoticism,” “Orientalism,” and “antiquity” have all been deemed valuable, practically justifying the rigidity of thought, stagnation, nostalgia, passivity, and nostalgic behavior.

Our ignorance of the intellectual trade-off during the new period and our unawareness of our own intellectual stagnation in modernity have resulted in us failing to recognize that the West has always regarded the “other” as non-Western; they once labeled other Greeks as “barbarians” and Christians of the Middle Ages as “antichrists”. The abnormal fetus formation of Orientalism and its heavy shadow over today’s awareness of inaccurate terminologies, classifications, and judgments have blocked our understanding of the culture and history of the Iranian world. As a consequence, we have placed our intellectual history under the history of the West.

The mention of a few examples of this inversion in today’s thinking will not be devoid of significance: The explanation of the establishment of government in Iran through the description of Aryan migration does not align with the conditions of Iranians and their ethnic dependencies. This entry into Iranian history ultimately echoes European racial thought. This kind of thinking is in conflict with a land where the concept of nationhood has been established by creating deep links between various cultures. Accordingly, reliance on oldness and racial authenticity has become a defining characteristic of renewed Iranian studies, in other words, what is known as a new nationalism, which in retrospect to a far-distant past has led to irrational and tension-causing results.

In another example, the basis for dividing Iranian history into “pre-Islam” and “post-Islam” constitutes a type of verbal historiography. However, verbal historians, like Tabari, do not advocate a discontinuous separation; rather, they emphasize the advent of the mission of the Prophet of Islam as the main axis of their chronology. This type of discontinuous division is among the characteristics of the new era, which has its origins in Christian chronology where in the acceptance of a new call and God’s intervention in history, a new epoch commences. From this perspective, the term “Age of Ignorance” takes on a new meaning. Among Iranians, however, such a term has never been used for their past in terms of thought and culture, unlike what happened among Arabs. Iranians, not only recently but also as emerging from their sources, have seen themselves as communicating with the thoughts of their ancestors.

For this reason, Iran was the only independent country in the Islamic world where a national government was reestablished. A continuous trend of thinking from the third century BC to the eleventh century AD can be traced in Iran. This continuity has been manifested not only in political thought but also in science, philosophy, architecture, literature, epic writing, music, and other cultural phenomena. For this reason, Iran’s Renaissance era took shape in continuity with ancient history and at the forefront of its Islamic period. Accordingly, naming the early Islamic era as “medieval” is an example of the post-Orientalism period in the history of post-orientalist science, which does not have meaning.

Westerners, in their extensive geographical descriptions ranging from Al-Andalus to the borders of China, have also placed Iran within the framework of the Islamic Caliphate. This perspective can potentially disrupt the coherence of our intellectual history because the intellectual materials of Islamic civilization, which have certainly been influential in Iran as well, are just one of several intellectual traditions of ours.

“Islamic Art” is an Orientalist term with no historical precedence in Iranian or even Islamic world thought. Similarly, terms like “Islamic philosophy,” “Islamic architecture,” and others are all new terms that reflect a distant and detached perspective, categorizing what appears foreign into larger classifications. In architecture, what is referred to as Islamic architecture is nothing more than the continuation of the Parthian school, which, as Mohammad Karim Pirnia states, continued in the form of the Khorasani school and spread throughout the Islamic world, extending to the western borders of the Islamic world alongside the Atlantic Ocean in Al-Andalus, where we still see Iranian architectural elements and gardens. Even in calligraphy, Iranians like Ibn Muqla (Ali ibn Parsi Baydawi from Dehqan Pars), who established the principles of six scripts, and ministers like Ahmad Sohravardi, Ibn Bawwab, and early great calligraphers such as the Ibrahimid dynasty of Sistan and Yusuf Sistani played a significant role in the spread of Kufic script.

Western scholarship, in pursuit of its own intellectual order and inclination to categorize unknown phenomena, has also introduced other entries like “Seljuk art,” “Mongol art,” “Timurid art,” and styles such as “Arabesque” and others. Placing the intellectual history of Iran within these classifications, which are based on dynasties and tribal structures, has brought forth contradictory concepts that are foreign to the nature of Iranian culture and diminishes the concept of Iranian nationhood to that of an ummah.

Iran’s continuity throughout the millennia is a continuity of culture, not merely tradition. It should not be forgotten that concepts like “tradition” generally find their meaning within the context of modernity. The misuse of the term “tradition” instead of “Tradition” in the Latin language is a result of our non-scholarly understanding. The incorrect translation and misapplication of this term in today’s language are a kind of new forgery that causes more confusion. Essentially, it is unclear what “traditional art” refers to and what it is applied to.

On the other hand, the categorization of cultural and artistic works into branches such as “static art” versus “dynamic art,” or “contemplative art” versus “technical art,” is also derived from European classifications. These classifications were originally devised in the West to create a legal system for both creators and consumers of artworks. However, since they do not align with the intellectual materials and historical realities of our culture, they have rendered a large part of our artistic and cultural potential into something sterile.

Through meaningless repetition of separating works into “marketable” and “artistic,” we even afflict the artist-industrialist with a kind of ailment of “orientalism.” We impose new valuation systems on them, forcing them to prove themselves under concepts like “creativity” and “genius” (which are inherently modern concepts) by changing the techniques and forms of their work into something unfamiliar.

On the other hand, the foundations of new thought in Europe are rooted in the latest debates with antiquity. But in Iran, it is topsy-turvy. Our modernism is synonymous with disregard for the ancients, not a contemplation of the ancient intellectual foundations.

Our false awareness of Oriental studies elevates anything for us merely by its age to the level of authenticity and value, embedding in us a regret for the past and a fear of losing anything from yesterday. This intellectual rigidity has caused yesterday not to evolve within us but to turn into an unchangeable text due to its antiquity.

About Indigenous Orientalism

The science of Orientalism was founded in contrast to the historical time of the West. For Westerners, the East was something vanished, whose remnants had to be preserved like a museum inheritance. This Orientalist perspective still dominates our perception of ourselves. Today, Orientalism is no longer as vibrant as a century ago. Chairs of Oriental studies, particularly Iranology, have less capacity, and we no longer witness that generation of great Orientalists from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The new generation of indigenous Orientalists are descendants of the East, reevaluating themselves using Western knowledge tools and materials. Our ignorance of Western sources and misplaced use of Oriental sciences have had destructive effects on Iranology studies.

Western scientists, as the identifier/subject, measure their cultural object against the foreign, outside of themselves. The fundamental point of this method is self-reflection in the mirror of the foreign, a reflexive feature in the concept of history in the modern era. However, in our case, lacking awareness of new science, we have also lost our old tools and are no longer able to recognize ourselves in the continuity of our historical spirit. Instead, we identify ourselves in a distorted manner, only distancing ourselves from ourselves and finding ourselves on different coordinates. Losing these coordinates, for example, placing the history of Iranian art under the concept of primitive authenticity, we lose our own subject and contemplate the illusion of “true history.”

In discussing the history of thought and new awareness

In this discourse, the utilization of modern theories serves merely as a perspective that opens the gates to the new concept of historiography. For instance, the general influence drawn from Hegel, in his treatise on “Phenomenology of Spirit,” reveals Hegel’s analytical stance regarding Iran’s historical position both as a philosopher of history and a philosopher of modern statehood. His intellectual apparatus discovers the system of the human spirit as absolute awareness and interprets human history as the history of the manifest spirit, discussing ruptures in awareness and historiography.

As previously stated, all Western historiography theories, from their inception, have developed based on the transformations occurring in the new social sciences framework, founded on the system of social science concepts and the understanding of European historical materials. Their uncritical application outside Europe will not untangle the knot.

On the other hand, these theories must be evaluated concerning the continuity and disruptions of historical developments relative to the concept of historical epochs. Essentially, there must be a genesis and a transformative beginning in the past for a renaissance or a new birth to occur afterward. Even in all these cases, a renaissance or a new birth does not necessarily happen. For instance, some cultures only have an ancient advanced period (such as Greece and Egypt) and have not moved into a later ancient period.

One of the most essential outcomes that must be derived from research on Iranian cultural history is an explanation of periods or periodization of Iranian thought and culture (which will be comprehensively addressed in forthcoming chapters). The elucidation and explanation of Iranian intellectual periods serve as a gateway to our understanding of disruptions and cultural continuity, as fundamentally, the historical nature of a doctrinal text and its internal transformation is reliant on cognizing the awareness transformation and the explanation of “continuity amidst its disruptions.”

“The attempt to present an image of the ‘cultural continuity of Iran’ is contrary because the cultural continuity of Iran has been made possible by the decline of thought. Despite invasions and defeats, Iran has remained as a country, and ‘national consciousness’ has persisted therein, which has enabled it to sustain diverse forms of thinking throughout its periods. Undoubtedly, its art and culture represent its most prominent aspects. Iran entered the period of ‘Late Ancient Renaissance’ after the ‘Early Ancient’ and ‘Transitional’ periods from the second and third centuries BC. The Iranian Renaissance or New Age occurred continuously alongside the Ancient Age. This period coincided with the ‘Early Middle Ages,’ namely the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries AD in Europe. Studying the cultural history of Iran in relation to the Early Modern Renaissance (1790-1500) and its later stages (1990-1800) is meaningless. Our relationship with the European Renaissance will be explicable after raising the question of our intellectual rigidity in the decline that followed the Iranian renaissance.”

Regarding the possibility of formulating a theory for subject histories (such as art and culture history) in Iran

There are indices in Iran that make the formulation of subject histories possible here and distinguish us in many ways from other cultures and territorial areas.

- Iran is a founding civilization. Cultures influenced by the founding foundations of other regions cannot own a subject history. For example, Belgian art history derives from elements of Flemish culture and, in dependence on Nordic Europe, is rooted in the Greco-Roman-Christian foundations. This means that a ‘text’ or historical meanings must be formed and its center must be a founding factor in world view and epistemology, to be able to bear historical seminal ideas for the birth of new thoughts. Otherwise, these centers usually do not have independent doctrines, meaning they do not have the possibility of establishing an educational system.”

- Iran possesses significant heritage in various fields such as literature, poetry, epic storytelling, visual arts, architecture, music, handicrafts, and more. This capability is less prevalent in other areas. For example, the Netherlands holds esteemed heritage in painting art, following the schools of Venice and Baroque, and has had influential developments in polyphonic music. It also has a history in Delftware ceramics, yet lacks comparable achievements in other aspects. Similarly, England has a notable history in literature and drama, but lacks foundational achievements in music history, architectural history, sculpture, and other areas that are defining and pioneering. With this argument, a comprehensive art history cannot independently be written for the Netherlands, Portugal, Morocco, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, or England.”

- Iran, in various fields, has established methods, styles, practical doctrines, and theoretical perspectives. From a theoretical perspective, the power of nomination in this culture is still capable of producing new manifestations from cultural crystallization.”

- The womb of the history of Iranian thought and culture has not only had the possibility of accepting the embryos of others, but the ability to give birth and give birth is still possible in it.

- In Iran, social connections have evolved from tribal and ethnic stages to the establishment of a historical nation, and existing artistic and cultural artifacts indicate a common characteristic as the spirit of social culture among various ethnic groups and categories residing in this land.

- In Europe, the formation of the concept of ‘Nation’ is perceived as entering a new age of awareness, as the state-nation concept became evident in the rupture from the sacred republican Christian in Europe. Europe, by forming the seminal ideas of national states and by creating the concept of the ‘historical individual,’ has opened up in philosophy of history. This historical individual is defined in the new era as the sole active agent in the world or a new status of intellect-subject, under national interests. This possibility has laid the groundwork for creating a new understanding in subject histories, including art history.”

- In Iran, the evolution from mythical concepts to heroic and romantic in the ‘national language’ and in written texts is established. To understand the role of the national language, a comparison with the cultural history of the Indian subcontinent can be illuminating. The dawn of Sanskrit language and literature is built upon strong and deep foundations. However, India is a diverse civilization, yet lacking in unity, and for this reason, a national language has never been established in this land. Consequently, texts like the Vedas and including the Upanishads have not been able to create a socio-historical coherence amidst the diversity of the subcontinent. Sanskrit remains as an ancient language that has not evolved alongside linguistic transformations in the subcontinent, and therefore has not played a significant role in general discourse.

In the modern era, historians refer to historical texts to study the factors and seminal ideas that create both “general” and “specific” discourses. This approach allows them to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the perceptible system of the national spirit in their written and oral intellectual heritage.

Although scholars and intellectuals have used Latin and Arabic in the cultural elite classes during both the Christian era and Islamic period in Iran, there are significant differences in the literary history and the legacy of the national language in these two periods. The dawn of literary languages in European national languages began with Dante in Italy. The longevity of public discourse in many of these languages does not exceed a consolidated literary era from 2 to 4 centuries. Texts that transmit memories and recollections of legendary-epic and ancient lyric literature are in Greek (Homer) and Latin (Virgil), not in national languages.

One of the hallmarks of Iranian culture is the emergence and continuity of a national language, national epics, and romantic literature dating back to ancient and Middle Persian eras, which then transitioned into Classical Persian as formal written texts were compiled. The antiquity of romantic literature, based on historical evidence and texts, predates Shahnameh or epic poetry. For example, poetic narratives like Vis and Ramin, or Bijan and Manijeh, have roots in Parthian literature. This highlights that Persian literature is not merely a linguistic domain but also a repository of memories and experiences reflecting the highs and lows of a historical nation’s spirit.

About Culture

In Greek, the term “Paideia” can relatively be interpreted as analogous to the Iranian term “farhang” (فرهنگ). During the spiritual rift in the Christian world, the transmission and expansion of this Greek root became impractical. The term “Culture,” through efforts of late medieval scholars and the onset of the Renaissance, introduced new meanings for this usage, which over three centuries evolved into its present-day concept. This loanword from Latin, derived from the agricultural term “Cult,” meaning to nurture plants and extract from the earth (today, the word “agriculture” in English stems from the same root), emerged.

Only through an extensive explanation of the term “farhang” in Iranian thought can one stand at the historical awareness coordinates. “Farhang” neither equals the contemporary concept of “culture” nor the Greek “Paideia.” This term is distinctly manifest in Avestan as “fra” and “hang,” recognized in Old and Middle Persian through to Modern Persian, extensively used in texts such as Yasna, Zand-i Wahman Yasn, Bundahishn, Menog-i Khrad, and Islamic-era texts.

The first part, “far” meaning abundance and vigor in Avestan, is understood in Iranian languages as splendor, the force of Mithra, and magnificence, which conveys an upward dynamic prefix in its application. The second part, “hang,” derived from the Avestan root “thanga” meaning brightness, radiance, and dignity, appeared in Old Persian as “hakhutan” in “farhakhut” and “ahakhutan,” and in Middle and New Persian it signifies concepts like emergence, rising from depth, spreading, and emerging from the base. Thus, this word suggests the equivalent meanings of drawing forth and uplifting.

Ferdowsi frequently used the term “farhang” in his Khwad-nameh: “The world is beneath our culture and tradition / The sphere is our shield against the enemies” “A gem without art is lowly and weak / With culture, the soul becomes vigorous”

Examining the inner layers of Iranian history outside the scope of artistic and cultural concepts is challenging. The historical society of Iran, what we now call the “Iranian world,” is a cultural society—not merely a political concept and certainly not a contractual society under the definition of state-nation.

According to Iranian studies, particularly European researchers, the prevalent belief is that the internalized thought of Iranian civilization is a blend of Aryan racial dominance, the advent of Zoroastrianism, and the imperial power of ancient Iran in the world. However, this narrative can only shed limited light on our heritage. To delve into the understanding of Iranian culture, this mistaken belief needs scrutiny and critique.

“The Aryan race” is fundamentally a new European narrative in Iranian history. Essentially, the term “race” does not have an equivalent in Iranian thought akin to the Western concept. In fact, in Persian, we do not have a word that corresponds to this concept. Major Iranian texts like Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh use “nijadgi” to mean “the essence of artistic excellence” rather than lineage, blood, or natural disposition. Iranian epic and romantic literature, from the oldest texts to the Islamic era, does not present examples where tribal or ethnic sensitivities, or the preservation of blood and ethnic-religious beliefs, are emphasized.

Most pivotal heroes like Rostam in Iranian epics are not purely Iranian in origin (Rostam’s maternal lineage traces to Zahhak, and Esfandiyar’s maternal lineage, the sacred hero Mazdiasna, traces to the daughter of the Roman king). Similarly, Iranian romantic stories often revolve around a romance between an Iranian hero or prince and a non-Iranian, such as Zal (ancestor of the Pahlavans of Iran) falling in love with a non-Iranian woman, or Bijan’s love for Manijeh, the daughter of Turanian Afrasiab, and so forth.

On the other hand, Iranian kingship embodies a concept linked with “farr” and bears resemblance to the Roman Empire or its “rex” in a manner that European historians and later scholars did not perceive.

Religion in Iranian culture, termed as “daena,” is an internal matter associated with awareness and conscience. From the Islamic period onwards, a gradual concept of prophethood entered Iranian thought in connection with Zoroastrianism and neo-Zoroastrianism, but the concept of prophethood cannot be inferred from the hymns of Ashu Zarathushtra in the Gathas. On the other hand, in various historical periods, predominant religions among Iranians were not limited to practices such as “Aeina Behi,” “Zoroastrianism,” or “Aeina Mazdiasna,” which exhibit discernible differences among them.

Recent research by Iranian scholars reveals the prevalence of religions such as Mithraism and Zurvanism in later periods. Over a long period of time and in a vast geography within the land of Iran, Buddhism gained significant traction in the east and Christianity in the west, as documents indicate, the Iranian temperament did not focus on the concept of Semitic-Aramaic religions. Thus, the explanation of Sassanian kingship as an empire of Aryan descent and Zoroastrian religion, which organized a wide realm encompassing all peoples and other religions, reflects an external perspective for which historical evidence cannot be found.

About Iran

The name Iran (“Land of the Aryans” or “Land of the Free”) appeared early in the history of this country, and “its ancient historical periods and modern eras have continued in various forms of awareness beyond historical ruptures.” What we call the “Iranian world” is not merely a political society, nor solely a contractual cooperation under state-nation frameworks, but rather a cultural phenomenon. Iran is a foundational and historical civilization, not a passive part of Orientalist scholarship or merely a component of Islamic civilization akin to the Holy Roman Empire. A renewed explanation of Iran from the perspective of modern awareness can provide a foundational basis for history.

Research in ethnomusicology indicates that despite the diversity among ethnic groups and geographical expanses, the music of different regions in Iran contains shared meanings within a cultural community. Iran’s artistic systems, including its music, stem from shared experiences and long-standing interactions among the peoples of this land, leading to the creation of collective meanings. For example, the music of the Pamir Plateau and the six maqams of Tajikistan share closer familial ties with the music of the Ahl-e Haqq tambur players of Iran, compared to the music of neighboring China. Similarly, shared motifs, patterns, and inner significances can be found in Iranian handwoven textiles across a vast region and among disparate peoples, each with their distinct tastes and requirements, yet collectively producing works of singular wisdom.

These shared elements extend across all fields, from literature and poetry to handcrafts, gardening, and architecture, interwoven into a heritage that is both cohesive and valuable. Additionally, Iranian national celebrations such as Nowruz are pivotal in generating historical momentum within the Iranian world and serve as our companions in navigating through ruptures and transformations in our historical spirit.

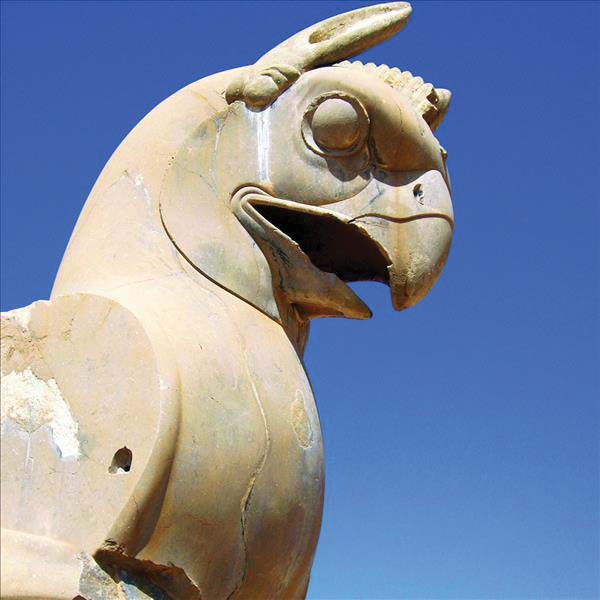

Iran is a society of diverse thoughts, yet a “kariz” or vein connects these diverse treasures, leading them towards unity. This vein originates from a source imbued with distinct characteristics. The legacy of Iranian thought, art, poetry, and literature from ancient times to the post-Islamic era refers to a jewel that has been recognized through the narrative of the mythical Simurgh, referred to by various names: “Senmuru” in Yasna, “Arta” at the time of the Bahmanids, “Khorram” in Vis and Ramin, “Hudhud” in Mantegh-ol-Tayr, and “Farrokh” according to Hafez. “Dastan Zal” and “Kariz” are also names attributed to it.

Its manifestation in Iranian literature, poetry, and arts resembles the mythical bird “Simurgh,” the lady goddess of Iran. Simurgh is not merely a teacher imparting lessons to a select disciple or messenger; rather, it empowers each individual with the ability to find themselves within their own existence and time, a journey of self-discovery or “pahlavani” that is the mission of every human being.

Zal Sepidmoi (Child of Light) is the home of “Simorgh”, the lineage of Iranian wrestlers. Simurgh nursed the Zal Sepidmoi, feeding him from her own breast, then returned him to the world and time. This concept of “irrigating the human with the actions of seed and grain” from the river Vehdati (= Huda) creates a different sense of “insight” in humans. By drinking milk from the breast of the nurse (Day = Taya = Dai = Deo = Dev), knowledge is transferred to humans. In the veins of the White Haoma, this knowledge is the spiritual blood; now he must use and expand this knowledge through his trials and searches.

This concept’s footprint in Persian literature has transformed into symbols like “drinking wine from the cup of Jamshid,” continuing its vitality. God (Arta) exists in every person, the source of illumination and insight in every human, capable of birthing the force of insight in each person. This deep and inexhaustible layer is the essence of Iranian culture, reborn and revealed in each historical epoch of thought.

postscript

- The genres of “self-portraits,” “still life,” and “landscapes” emerged as a Christian tradition in European art post-Renaissance, unlike any example in the cultural heritage of other civilizations. In fact, the “self-portrait” symbolizes the transformation of spirit, akin to a faithful perspective, and reflects the ups and downs of the believer’s conscience as a mirror of Christ’s trials. For the artist, there is no greater truth than the nature of God and human nature, and it is this unity that is perceptible. Rendering one’s own face reflects this meaning: “God is spirit, and those who worship Him must worship in spirit and truth” (Gospel of John). Similarly, the repeated and varied portrayal of objects and things in the curtains of “still life” is a symbolic manifestation of the manifest abundance of the Word (Logos or God) in the world, and “landscape” is a revelation in the relationship between the Creator’s place (Logos) and creation and acceptance of grace.

- The establishment of Aristotelian logic among theologians of the Paris school, its expansion in the views of Thomas Aquinas, and the beginning of the modern style of painting are complex and detailed discussions that we will delve into in the future.

- In this sense, the reality of an artistic work is the multiplicity of “ideas.” And this reasonable concept that human can only establish a relationship with the absolute is supposed to be that idea which in Christianity is “Logos” or “The Essence” is unreasonable.

- The term “Renaissance” was first used in the sense of studying the culture of a period in the mid-19th century, as employed by Jacob Burckhardt.

- This topic is further elaborated in detail in the article “Illusion” in volume 31 of Herfeh: Honarmand Magazine.

- A more detailed explanation of this discussion is provided in the article “Inversion of Illusion” in volume 33 of Herfeh: Honarmand Magazine.

- Dr. Javad Tabatabai, ‘’reflects on Iran’’.

- In these cases, the experience of peoples can lead to the creation of a distinct style.

- A period of Indian culture has the potential to formulate a thematic history that the national government has utilized in administration, science, and literature, as seen during the short periods of Ashoka and the rule of Babur.

- The profound relative terms “full” and “plenty” have a deep connection with the ancient Simurgh tale, which we will explore in the future.

- The repeated emphasis on Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh may create the misconception that this work has only been a renaissance of Iranian culture in Persian-speaking contexts. However, the legacy indicates its widespread influence shortly after Ferdowsi’s death. Thirty years after its completion, Qatran Tabrizi recalls its importance, and after two centuries under its influence, Sasuntsi Davit’s epic is sung in Armenian, followed by Shota Rustaveli’s Knight in the Panther Skin in Georgian. Abdari Esfahani translates it into Arabic, and soon after, a Kurdish Shahnameh is authored during the establishment of the Khatai Turks by Muqarrin Khali.

- Sayyid Jawad Tabatabai, ‘’the decline of political thought in Iran’’.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.