An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

It is important to reiterate at the outset that these lectures do not claim to present a “history of Iranian art and culture” in the strict sense. Writing a text on the history of Iranian art and culture, which spans a very long period and encompasses a vast array of branches with unparalleled breadth, requires preliminary work in various fields and the fruition of foundational research in multiple disciplines. Even with these prerequisites in place, the advancement of such a grand project may be beyond the capacity of a single individual. As the title suggests, these articles are merely an introduction to a discourse that we hope will lead to the development of a theory explaining Iranian culture and art. It would be highly encouraging if current and future researchers critically engage with this work, identify its flaws with keen insight, and refine them to establish a logically sound foundation for better understanding in this area.

In this lecture, before proposing a periodization for the history of Iranian art and culture, which will be discussed in the next session, it became necessary to first address the topic of writing art history itself, along with some of the important challenges and considerations surrounding it. Therefore, some points from previous lectures have been reiterated, and additional aspects have been introduced as required by the current context. This has been done to sensitize the reader’s mind to some fundamental issues that deserve attention at every step taken in the formulation of art history.

General Notes on the Historical Development of Cultures

Every founding culture emerges around a “great idea” that has gradually taken shape. Along this path, communities, based on their lived experiences and in relation to the needs and potential of their environment, make innovations and establish their own intellectual systems. 1 In previous lectures, some of the factors contributing to the formation of five founding cultures and the differences in their nature were discussed. 2

It is evident that the journey through history inevitably brings about crises and challenges to varying degrees. One of the differences in cultural characteristics lies in how cultures understand crises, how they confront them, and how they navigate through critical historical moments. The historical life of Iran has been a combination of becoming and permanence, or transformation and continuity. This dual combination of renewal and continuity sets it apart from some other cultures, such as China or the Indian subcontinent. In Iran, crises have brought about significant changes or “ruptures,” and the continuity of our culture has been maintained amidst these changes. Each of these crises has left a mark on the cultural character, which can be identified with careful attention as a historical turning point. In this sense, the interval between two ruptures can be termed a “period.”

One of the tasks of art history—like any other thematic history—is to identify ruptures and name periods within the historical context under study. It is obvious that with such a definition, the periods of one culture cannot be directly aligned with those of other cultures.

Each founding cultural center, with its semantic system arising from the core idea of that culture, creates appropriate means to recognize itself and understand its relation to others. In Iran, where the conditions for continuity through crises and entry into new periods have involved reorganizing foundational theories, confronting new texts, and reflecting in the mirror of the “other,” the complexity of crises increases. However, the secret to the continuity of Iran’s cultural center throughout history lies in this process of becoming, renewal, and transformation. Each time, by inventing tools suited to its nature, Iran has succeeded in renaming and redefining itself. Therefore, the formidable challenge here is that the path to resolution must emerge from within the heart of the crisis-ridden domain itself. This is what, as Dr. Javad Tabatabai puts it, transforms Iran’s “issue” into Iran’s “problem.”

The key to the continuity of Iran’s cultural center throughout history has been its characteristic of “becoming,” or its constant transformation and renewal, which has typically been made possible by looking into the mirror of the “other.” In this context, overcoming crises has depended on the ability to reorganize foundational theories, confront new texts, and enter new periods.

This very process adds to the complexity of the crises because overcoming each crisis here requires the invention of tools that are in harmony with the nature of this culture, allowing for the redefinition of various aspects of the culture. The formidable challenge lies in the fact that the solution to the crisis must also emerge from within the crisis-ridden domain itself, which, as Dr. Javad Tabatabai puts it, transforms Iran’s “issue” into Iran’s “problem.”

A “problem” entails complexities of a different nature, lacking a straightforward solution. It requires examining the hidden and multifaceted layers, much like observing a living organism that is in a state of constant becoming.

Typically, Iranologists in various fields of research have focused on the “issues” of Iran. However, such an approach does not penetrate the core of matters and remains on the surface because this perspective overlooks a crucial factor underlying all the problems: the “idea of Iran.”

Reflections on Art History Writing

The Focus of the Humanities on Characteristics and Differences

As noted in previous discussions, in the modern era, knowledge—particularly in the humanities—has been built on the understanding of “differences.” Disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, and linguistics have emerged based on the identification of distinctions among societies. Generally, the advent of the modern era brought a shift in awareness, revealing that not all societies can be explained under a single system of “good and evil.” 3 This new understanding cast aside the concept of a universal “world history,” which had been a shared idea among the Church Fathers and Islamic theologians.

Therefore, the first step in any form of historiography, including art history, is to pay attention to the subject matter with regard to its differences from other cultures. It is essential to ask where the distinguishing features of our subject of study lie. Ideas that attempt to apply established patterns from other cultural contexts to the historical materials of different cultures, or theories that seek to offer a universal model for humankind while ignoring differences and explaining phenomena within a single historical order, such as those aiming for a “global art,” still have roots in pre-modern awareness. It should be noted that concepts like “left internationalism,” although emerging as a modern ideology, inherently carry a reinterpretation of the return to the theological concept of a unified ummah.

The Importance of Naming

The continuity of historical life for any culture necessitates the ability to name the various periods of its historical development in relation to contemporary awareness. The loss of this capability manifests as marginalization or an inability to contribute to intellectual production. In other words, the ability to “name” periods in accordance with the awareness of the time serves as a record of the historical spirit of the people.

The concept of “naming” also has a subtle connection with the notion of ownership, as the act of naming carries a legal dimension. In essence, naming is akin to establishing the identity of a people who share a common memory and possess a unique ontological system.

It is clear that every living cultural system understands other systems in relation to its own sphere of awareness and names them accordingly. Thus, it must be noted that, on the one hand, naming is necessarily constrained by a specific “sphere of awareness” and is subject to change with shifts in this sphere. On the other hand, this fallibility does not render it unscientific! This is a recurring paradox in the history of thought; from this perspective, every act of naming is constructed and dependent on a particular body of knowledge and theory within which thinking is made possible.

The continuity of historical life for any culture requires it to name the various periods of its development in relation to contemporary awareness. The concept of “naming” has a subtle connection with the notion of ownership, as the act of naming carries a legal dimension. In essence, naming serves as a means of establishing the identity of a people who share a common memory and possess a unique ontological system.

Each “period” is akin to a new orbit formed around the gravitational pull of a focal point within a historical system, or metaphorically, a new branch growing from an ancient trunk. Therefore, without the activation of the naming capacity of awareness or the recharging of the core of a cultural system, no new period can be established. In this sense, every period, even when undergoing multiple ruptures, relies on its prior formative conditions.

Moreover, it should be noted that only within the framework of a cultural system can a perspective for observation be established, and consequently, the capacity to name historical periods develops. This is because each cultural system uniquely contains the seeds of specific awareness, which, given the capacity for continued vitality, fosters the progressive force of awareness within it. The branches of a cultural system remain alive, dynamic, and productive as long as they are within the gravitational field of their core.

The Impact of Ideologies on Naming

Thus, the seemingly simple issue of “naming” carries numerous subtleties. At the core of any naming process or categorization and periodization of historical and cultural materials lies a potential “will” to shape the framework of thought. It is not surprising, therefore, that with the strengthening of any ideological inclination, names may change. Ideological perspectives have even had the power to appropriate the initial seeds of a culture’s emergence for their own interests. Since this involves many hidden and overt interests that can potentially shift the centers of power, there is always the possibility that, in the pursuit of sectarian or political goals, theories borrowed from different fields of study might be used to radically alter the nature of historical heritage—from intangible heritage to the entirety of a country or culture—by changing names and thus fundamentally disrupting it.

In modern awareness, knowledge—particularly in the humanities—has been built on the understanding of “differences.” Disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, and linguistics have emerged based on the identification of distinctions within their respective fields of study across different societies.

The first step in any form of historiography, including art history, is to examine the subject matter with regard to its “differences” from other cultures and to ask where the distinguishing features of the subject of study lie. Efforts to apply established patterns from one cultural context to historical materials from different cultures, or attempts to overlook differences and present a universal model for humankind, explaining phenomena within a single historical framework, still have roots in pre-modern awareness.

Determining the Origin of History

The first step in any branch of historiography is selecting the starting point or “origin.” This choice clarifies the historian’s overarching perspective, as the origin represents the most fundamental milestone in the subject matter, allowing for the division of time into before and after this point. In thematic histories, each field proposes a convention for the “origin” and the separation of “history” from “prehistory” according to its own materials. For instance, in Christian theological history, the entry of God into history is recognized as the origin. In the history of science, the extraction of metals is often considered the origin, while in the history of historiography itself, the advent of writing is typically viewed as the starting point.

Establishing a general and universal convention for distinguishing history from prehistory may be feasible and meaningful in certain disciplines, such as some branches of the natural sciences. However, in other fields where the primary focus is on understanding the unique characteristics of each culture, standardizing societies would negate the study’s core objective. For example, in the history of the arts, applying a single model to mark the entry into history hinders the understanding of the distinctive features of the subject under study. In fact, the process of development that gave shape to the unique awareness of each founding cultural center varies from one to another. The discussion of the beginning of history in a particular cultural center is meaningful only when considering the “core idea of establishment” within that culture.

Each artistic school is associated with shifts across various domains

In the study of art history, it must be noted that the emergence of each “artistic school” is not limited to events within the realm of art itself. Rather, it coincides with broader shifts in the era and is influenced by various achievements across different aspects of social life, which create the conditions for the emergence and development of that school.

Writing the history of art is not feasible for all cultures

Examining the achievements of the five foundational centers, we find that some have flourished and thrived in certain domains, while others remain dormant and peripheral in different areas. As mentioned in previous discussions, only three centers, in a meaningful historical trajectory and across various branches, have produced achievements that can be categorized under “art history.” These centers, for which an independent history of art can be written, are: the European center (Greek-Roman), China, and Iran. 4

The civilization that developed under the Western Church recognizes the ancient cultural sphere as one of its foundational elements, according to its unique conditions. Therefore, it begins its historical narrative with the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and then moves to the Greek-Roman sphere as heirs to the Mesopotamian civilizations. This framework, which is strongly upheld, remains as the “official” and reference narrative in educational contexts, based on a tradition rooted in ecclesiastical thought.

Reflections on the History of Western Art

Art history research in Europe, often framed as “global art history,” typically begins by explaining the origins of human history through a special definition of “prehistory,” focusing on the era of magic. It then proceeds to trace the roots of European Christianity in the ancient cultures along the Nile and the achievements of the Biblical authors in the Eastern Mediterranean, considering these as the “dawn of art history.” Occasionally, this framework also includes a brief mention of Iranian art as a small part of this Eastern cradle. 5

European art historians face a unique situation because the most significant and lengthy periods of the development of this field lie outside European civilization. This is a distinctive feature of the European cultural sphere. Following this period, attention shifts to Greece, or what Gombrich refers to as the “Great Awakening,” which is considered the heir to previous civilizations. After Greece, the focus moves to the art of the Roman civilization.

The term “Middle Ages” is used to designate the period between two prominent eras in European cultural history: the classical Greek-Roman period and the Renaissance. This Middle Ages span nearly a millennium. It is common practice to examine art and achievements from outside the European civilization during this “Medieval” section. This includes, for instance, art from the Eastern lands, categorized under “Islamic art” (in parallel to the Christian era in Europe). Additionally, without much logical justification, art from the Indian subcontinent and the Far East is often included in this section. This marks the endpoint of discussions on non-European cultures; in the tradition of European art historiography, references to non-European centers are generally discontinued with the onset of the Renaissance.

Common Themes in European Art History Theories

Reflecting on the foundational theories and the views of theorists who introduced the concept of “art history” in Europe, it appears that despite some differences, there is almost unanimous agreement on several fundamental principles. From the initial framework proposed by Winckelmann (1755) to the insights of the most erudite theorists of the 20th century, a common denominator can be summarized as follows:

- Focus on the History of European Art: All historians think about the overall history of “European” art, rather than the art history of each European country separately.

- Consensus on Greek and Roman Foundations: There is a unanimous agreement among historians on the Greek and later Greek-Roman periods as the core origins of European “civilization” and consequently its “art.”

- Emphasis on Plastic Arts: For these theorists, art history encompasses only the plastic arts, or visual arts, that involve form and structure.

- Definition of Art and Fine Art: Historians have generally adopted the definitions of Art and Fine Art as understood in the Renaissance and later periods.

- Role of Religion: The topic of “religion” and its roots is a central aspect in defining the foundational art regions of the world, with a particular focus on the development of Christianity, often referred to as the “Holy Land.”

- Importance of Language Family: Highlighting the language family as a primary vehicle for transmitting spiritual heritage is another common element in all theories.

These six principles can be considered the pillars of the “text” of European art history. This text gradually evolved in two branches and two cultural spheres: the Latin sphere and the Germanic sphere. In the Latin civilization sphere, the history of art writing can, with some leniency, be traced back to Vasari (mid-16th century). In this tradition, in addition to the aforementioned elements, a seventh factor has been introduced: the consideration of political thought and cultural commonalities.

In the Germanic civilization sphere, in addition to the six principles mentioned, issues of race and ethnic commonalities have also been a focus.

Here is a more detailed explanation:

In writing the history of art, European historians focus on the achievements of the entire Western world. This is because it is rare to establish a comprehensive art history for each European country that encompasses various fields; that is, not all artistic traditions across European territories have a substantial historical precedent. For example, the Flemish territories have a distinguished heritage in painting and a notable history in the development of polyphonic music, but have played a less significant role in other arts. 6 Similarly, England has a valuable heritage in literature and theater but lacks a significant historical precedent in the development of music, visual arts, and architectural schools.

The first nation-states in Europe were established gradually from the 14th and 15th centuries 7, beginning with France and England, followed by the Kingdom of Prussia and, later, Germany. Alongside this process, there was a renewed interest in the concept of “N Renaissance” or “rebirth,” which focused attention on Greece. Thus, there is a fundamental connection between the formation of nation-states and the organization of civilization history, and consequently, the history of arts.

European countries, drawing from the legacy of Greek-Roman art, can provide an account of the origins of their own art and culture. Thus, they view Greece as their foundational center. However, the Greek center itself has a distinct fate: it did not continue beyond the early ancient period and remained largely dormant during the long and significant Christian era and later during the Renaissance, where it played a relatively minor role.

The writing of European art history has been based on visual arts, as these art forms offered the best means to serve the shared cultural framework of European cultures under Christian faith.

In European historical consciousness, shared elements such as the uniformity of religion (official Christianity), philosophical thought, embodied art, common racial roots, and similar myths have become institutionalized. This historical background has influenced Europeans’ judgments and perspectives on other civilizations to the extent that, in the writing of art history, they have used concepts such as “purity,” “single-source narrative,” and “non-synthetic” as the basis for defining and elevating the role and contributions of each culture in documenting historical achievements. From this perspective, centers considered foundational or originative are those where the characteristics of non-synthetic and single-source traits are more pronounced.

Europeans explain shared mythological foundations and linguistic commonalities through their common roots, which they refer to as “Indo-European.” Generally, the classification based on the “Indo-European” creative index has had significant impacts on the fields of archaeology, linguistics, anthropology, and art history. 8

For centuries, Latin was the shared language of the scholarly domains in Europe and nearly the sole language of culture and thought. In this context, the experience of “multilingualism” in historical, political, and cultural communications was non-existent until the modern era. Unlike the bilingual or multilingual inscriptions such as the Behistun Inscription and many Persian inscriptions, there are no similar examples in European historical documents (with the exception of the Rosetta Stone, which was related to the conquest of Egypt).

The development of national languages in Europe is a relatively recent phenomenon, and its tardiness is a notable subject of contemplation. European countries, in their modern national languages, lack ancient written texts in their native tongues. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and the Old Testament and New Testament are shared European texts. Homer’s works were composed in ancient Greek and became accessible to the general public through translation. Similarly, historically, the Latin translation of the Bible was the only accepted translation for the Roman Church.

European historians, in writing the history of art, rely on the achievements of the entire Western world; because it is rare to establish an independent art history for each European country that encompasses various disciplines. This is to say, not all artistic traditions have a substantive history in every European territory.

The foundation of European art history writing is based on Art Plastic, or the “visual arts,” because this branch of heritage has created a unified spirit in conveying concepts. By examining the achievements within this field, a cohesive historical narrative can be constructed.

Distinguishing ‘Decorative Arts’ from ‘Fine Arts

One of the significant classifications in the European art tradition is the distinction between ‘Decorative Arts’ and ‘Fine Arts.’ The term ‘Fine Arts’ emerged from foundational concepts in Christian theology and is linked with a particular understanding of ‘Love’ in Christianity. This terminology and the resulting division stem from a transformation that occurred after the Gothic period, during the medieval era. Étienne Gilson, in his valuable works The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy and Introduction to the Fine Arts, aids our understanding of this rift in European thought: “Every cause produces an effect similar to itself. If the world, in the view of Christians, is a product of God — and here ‘product’ means ‘creation’ — it must be an entity similar to God.” 9

Gilson demonstrates that around the 13th century, a theological debate emerged within Christian theology, where Thomas Aquinas opposed the views of Augustine’s followers. The disagreement centered on two different interpretations of the concept of divine likeness. Although both perspectives view the heavens as reflecting divine likeness and thus possessing ‘similarity’ to it, Thomas’s philosophy represents the first philosophy where “similarity to God seeks its way into nature,” “transcends order, proportion, and beauty, penetrates into the natural form of the world, and is joined with the effect that objects as causes impart to each other.”

Given the dominance of Thomas Aquinas’s views as the most influential thinker and theologian of the Middle Ages, and the theoretical framework he developed based on Aristotle’s understanding of God and nature, a significant intellectual shift occurred among late medieval artists. This shift laid the groundwork for the early Humanism and Renaissance. Artists, who had previously been referred to as Engineers and worked within the geometric interpretation prevalent in Gothic art under ecclesiastical designations, 10 gradually developed a style that emanated from this new awareness.

European historians, in line with their historical materials, have placed “visual arts” at the center of their focus and analysis. In contrast, from the perspective of Iranian culture, it would seem natural to seek the connecting roots of various branches of art in literary heritage, stories, and especially poetry.

It is possible that societies which have not played a significant role in the course of intellectual history may be compelled to imitate and repeat the European art history model. However, in a context like Iranian cultural sphere, using this model as a basis for historical awareness and for structuring educational and research foundations would only lead to a dead end, rendering much of the historical heritage undervalued.

This style was grounded in the knowledge established by St. Thomas, who, as mentioned, proposed that “resemblance to God sought its path into nature.”

From this point forward, the principle of Thomas’s “analogy and comparison” found its way into the work of Renaissance artists as the method of “comparison and observation.” This introduced a break from previous schools and styles, leading to a new understanding distinct from Greek techne and medieval engineering, which was based on Art (= relationship) or connection with God. The term Art [meaning connection, junction, or link] was initially borrowed from the Aristotelian classification of knowledge and medical science. In the later transformation, it combined with the prefix Beaux to form the new concept of “beauty” or “aesthetic” in the ideas of Thomas Aquinas, giving birth to Beaux Arts, fine Arts, or “fine arts.” 11

In the works of artists from this era and beyond, the concept of “resemblance” and methods of “mimicking” reflect more than just a superficial difference from previous traditions or non-European arts. From this period onward, what came to be known as “fine arts” referred to the “effect,” which exists in relation to its “cause” through “resemblance.” In this understanding of the relationship between humans and existence, the intensity of an entity’s being is directly proportional to its resemblance to its creator; thus, entities are as much as they exist, “similar to the divine.” In this view, just as the “Incarnation” represented God’s appearance in human form through Christ, so too did God impart His beauty to the elements of the world.

Thus, in the realm of European artists, a triad emerged from the interplay of “resemblance” with “observation” and “comparison,” which formed the foundation of art in the modern era. Under the system of “observation, analogy, resemblance,” the “grace” obtained through the pursuit of “God’s beauty in objects” came to be known as “fine arts.” Paintings classified as “still life,” especially among Protestant painters, reflect this worldview and approach to the act of painting.

From the Renaissance onward, a clear rupture in the style and approach of artists emerged, resulting from a new understanding of beauty, nature, and divine craftsmanship. This new style, due to its direct connection with the concept of Christian incarnation, first manifested in visual arts, particularly in painting. 12 Over time, the collection of artworks gradually reached a certain uniformity, with shared elements defining the period. Consequently, the separation and divergence between old and new styles led to the categorization of earlier arts, such as stained glass, remnants of geometric patterns, and old church decorations, under the label of “decorative arts.” Those who created works with this new perspective were termed Artists, while others were referred to as Artisans.

In tracing the historical evolution of European art, a significant point for us is the separation of “decorative arts” from “fine arts.” This transformation occurred amid theological debates during the Middle Ages. According to Thomas Aquinas, every effect is related to its cause through resemblance; that is, beings are similar to the Creator to the extent that they exist, and “fine arts” refer to works created based on this principle of resemblance.

Thus, the concept of resemblance and the methods of imitation under this understanding represent more than just a superficial difference from previous traditions or non-European arts.

The combination of the elements of “resemblance” with “observation” and “comparison” resulted in a triad that defined the essence of art in the modern era. Under the system of “observation, comparison, and resemblance,” the “grace” achieved through the search for “the beauty of God in objects” came to be known as “fine arts.”

Paintings classified as “still life,” particularly among Protestant artists, embody this same perspective on the world and the practice of painting.

In this understanding, just as the Incarnation represented the appearance of God’s face in the human form of Christ, so too did God bestow His beauty upon all elements of the world.

General Principles of Fundamental Theories in Western Art History

Now let’s take a brief look at some of the most well-known viewpoints in the organization of art history, which, within the general framework previously mentioned, differ in details and orientations, and some of which are also related to the work done on the history of Iranian art. 13

- Ethnocentric European, Greece-centered, and Ecclesiastical-focused perspectives (Winckelmann, Jacob Burckhardt)

- Positivist approach (Jensen)

- Descriptive approach to analyzing visual elements of artwork (Helen Gardner)

- Linear structuralist approach in weaving a chain that connects various works of an artistic tradition, and even beyond it (Gombrich)

- Iconological interpretation (Panofsky) [one of the foundational approaches in modern art history]

- Sociological-economic interpretation influenced by the left Hegelians (Arnold Hauser; Social History of Art)

- Interpretation based on “theology of salvation” influenced by the French Revolution (Proudhon)

- Liberation theology or a new form of Christian theology with a Marxist inclination within the Latin American Church. [This perspective can be seen in the reactions of New York leftist critics to the works of Siqueiros and Diego Rivera]

- Interpretation based on “sacred history” under the critique of metaphysical history and in combination with phenomenological knowledge (Heidegger; The Origin of the Work of Art)

- Cultural history ideas, focusing on the methods of production, economics, and dialectical outcomes (Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag)

- Focus on Christian theology and intellectual developments of the Middle Ages in explaining artworks (Étienne Gilson)

- Semiotic approaches in the interpretation of art history and culture (Umberto Eco)

- Mythological approaches

- A combination of leftist perspectives and descriptive approaches (John Berger)

- Modernist critiques and traditionalist modernism based on sacred history (René Guénon, Titus Burckhardt, Frithjof Schuon) [The discussion of “Islamic art” is a product of this perspective.]

- Focus on sacred art, based on cyclical sacred history (Ananda Coomaraswamy) [Interpretations emphasizing celestial symbols and calendrical events are products of this perspective.]

- Postmodern interpretations of the post-colonial era, including combined and sometimes leftist approaches (Foucault, Derrida, Sartre)

- Neoplatonic-phenomenological perspectives (Merleau-Ponty)

- Approaches based on European historical aesthetics (Benedetto Croce)

- New theories in classifying knowledge and interdisciplinary understanding from the perspective of modern awareness (Gaston Bachelard: combining psychology and philosophy, etc.)

- Interpretations based on the history of theology and philosophical thought under phenomenology, focusing on neglected layers in rational-empirical or reason-and-experience-based views (Henri Corbin’s attention to the “World of Imagination” in Iranian thought)

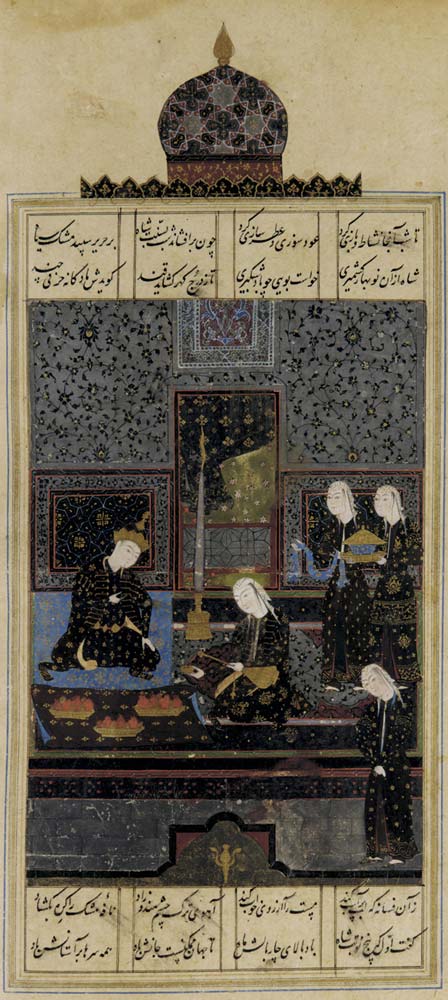

- Work based on textual criticism (Basil Gray focusing on Iranian miniatures, George Farmer in the field of musicology)

- Objectivist positivist perspectives (In the context of Iranian heritage: Arthur Upham Pope and Ackerman)

- Research based on archaeological-objectivist findings (Roman Ghirshman)

- Attention to the necessity of a tailored theory for studying other cultures (Study of Iranian art: Graber, Frye)

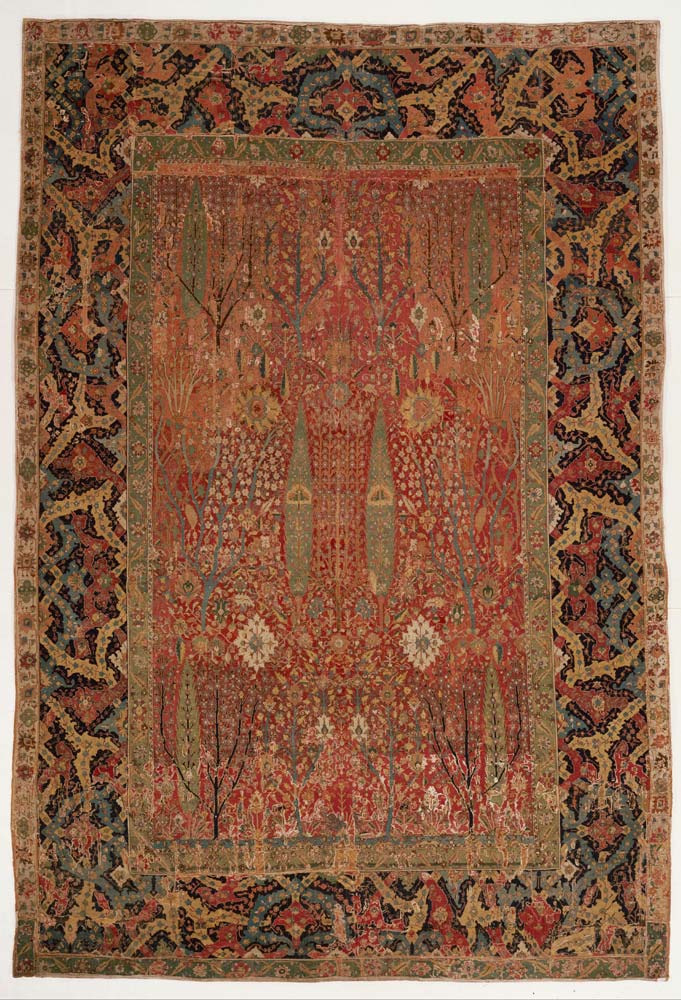

It is natural that when European culture encounters the heritage of other civilizations, it evaluates their works according to the course of its own historical developments, often categorizing them as “pre-modern” and placing them in the realm of “decorative arts.”

However, it is strange that we apply this external perspective ourselves. The system of Iranian art is based on different foundations and cannot simply be categorized according to a historical trajectory with different roots. It is evident that “embodiment is not a universal type of awareness.”

Reflections on the Characteristics of Iranian Art History

Paths Traveled in the Study of Iranian Art in the Modern Era

In the previous section, references were made to scholars and orientalists such as Pope, Ghirshman, Basil Gray, and others who have worked on various branches of Iranian art. In the modern era, Iranians also encountered these new forms of historiography and made various efforts to redefine art and understand its developments. Besides translators who tackled theoretical texts in different levels of art history and articles (Ali Naqi Vaziri, Isa Behnam, Jalal Sattari, Ali Ramin, Yaqub Ajand, and many others), researchers and writers also ventured into this field. Their contributions can be summarized in the following categories. The history of this field, like all other periods of its fluctuations, includes a diverse range of activities and has been affected by various challenges, from ideological stagnation to the decline of intellectual foundations. Any new effort is destined to fail without considering the previously traveled paths. A detailed critique of the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches is needed. Here, only a list is provided with the aim of giving an overview of our current position relative to what has been achieved so far and the quality of the results handed down to the next generation.

The tradition of the Self-Portrait in European painting closely conveys the concept of Christian love. The highest expression of European Christian culture is manifested in the love of Christ. Thus, depicting the image of Christ, the events of His life, and exploring reflections of these in the mirror of the other, occupy a revered position in the ultimate cultural framework.

European painters, through the repetition of this artistic tradition over their lifetimes and their insistence on portraying themselves through the passage of time, capture their reflections in an alterity that parallels the depiction of Christ’s life events.

Such behavior is a product of European Christian interpretation and finds no comparable tradition among Coptic, Ethiopian, or Nestorian Christians.

Types of Anti-Modernist Orientations:

• Anti-modernism with a Traditionalist Bias: In the works of Seyyed Hossein Nasr, following the ideas of Frithjof Schuon. 14

• The combination of René Guénon’s anti-modernism with the idea of sacred art: In the early works of Dariush Shayegan (Mental Idols and Eternal Memory)

• The combination of anti-modernism with postmodern discussions: In the later works of Dariush Shayegan (Cultural Schizophrenia)

• Anti-modernism with the idea of returning to the self: (Jalal Al-e-Ahmad’s critiques)

• Efforts based on archaeological-historical achievements, influenced by the new European nationalism (Jalil Ziapour)

• A Marxist-based perspective influenced by Eastern European schools of thought (Aryanpur; Sociology of Art)

• Writings scattered across a wide range of non-specialized and occasional texts to enlightening ideas (Es’haqpour, Jalal Sattari, Shahrokh Meskoob, Ehsan Yarshater, Babak Ahmadi, and others)

• Approaches based on codicology (Iraj Afshar, Yahya Zoka, Shahriar Adl, Mehdi Bayani, Gholichkhani, and others)

• Scientific approaches in the preparation of artistic entries, whose significant outcome has been the compilation and collection of encyclopedias (Professor Rouin Pakbaz; Art, Ehsan Yarshater; Encyclopædia Iranica)

• Efforts to coin terms and name eras and schools by rethinking the tradition of the ancients and combining it with new knowledge (Malek o-Sho’arā Bahār, Mohammad Karim Pirnia)

It seems that two of the most significant works that laid the foundation for new research and criticism in Iranian studies were first, Bahar’s Stylistics, which was written in the field of literary history and pioneered the establishment of terms; and second, Pirnia’s lectures on Iranian architectural art, which explained the art of architecture. In their work, a reliable foundation was established that became trusted, to the extent that any further steps in these two fields must necessarily be taken in relation to it, whether in critique, refinement, or accuracy.

In other branches, we can also refer to Iranological research that approached its subject from a perspective similar to that of Bahar and Pirnia; namely, a view from within the culture and an effort to renew ancient knowledge. Among these are the studies of Zabih Behrouz, Mohammad Moghaddam, Mohammad Ali Imam Shoushtari, Mohammad Mohammadi Malayeri, and Amir-Mahdi Badi’. These early scholars, relying on both ancient and modern knowledge and their mastery of sources, opened a critical perspective on the official research in European universities and, in this regard, have a precedence in modern criticism.

In continuation of this path, it seems that the collected works of Dr. Javad Tabatabai represent some of the most comprehensive scholarly research in modern Iran. His project can be considered a foundational theory for the modern era, one that has a meaningful relationship with the context of this culture. Although his research is focused on the history of political thought, it also sheds light on various periods, transformations, and ruptures, potentially illuminating other fields of Iranian studies as well.

Efforts to Create a Theory Based on an Internal Perspective

Javad Tabatabai, in his collection Reflections on Iran, states: “For over a century, the uncritical adoption of concepts and categories has been one of the scourges of historiography in the Iranian world. This issue arises from the fact that historians, instead of striving to develop the concepts and categories of a historical period based on its own materials and explaining historical transformation, tend to impose their own ideology as the primary framework and force that framework onto historical materials.”

Any research “requires concepts and categories that are derived from within the historical materials of Iran, because this history has characteristics that, even if they can be found elsewhere, have different explanations in the context of Iranian history. One of these characteristics is the historical continuity of this country, which Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari pointed out at the beginning of the Islamic era.” This historical continuity can be explained under the concept of Iranshahr. “Iranshahr is a category in Iranian historiography and is by no means a slogan in political struggle.”

The focus on the subject of naming begins with the name Iran itself, a name that has been deeply ingrained in the consciousness of the people of this region for a very long time. Ancient names typically carry the “idea of the formation” of a culture. The meaning of Iran (= “Land of the Free”) leads us to the foundations and preconditions for the formation of this culture and its nature deep in history. In this name, we find a reference to the nature of a historical society that has been based on the unity of multiplicities. This is because it does not refer to a specific tribe, bloodline, or race, nor does it trace back to a dominant tribe, or even serve as a geographical description. Rather, it highlights a characteristic that can encompass all the people residing in a vast and diverse land. 15 Thus, the name Iran can still function as a “historical message” for the people of this culture.

Any research on the history of Iranian art and culture necessitates attention to the “geography of Iranshahr” or the “Greater Cultural Iran.” This is because only by considering all these parts together can we reveal a comprehensive picture. If, as has become common practice recently, our explanation is limited solely to the borders of modern-day Iran, many of the greatest achievements of cultural Iran would be fragmented under new names, and the role and significance of its diverse and scattered parts would be utterly distorted.

Separated cultural centers like Herat, Baghdad (Ctesiphon), Samarkand, Shirvan, Kashmir, Tbilisi, and others are each pieces of a larger mosaic. The heirs, owners, and creators of this vast culture become sterile and silenced without the possibility of synergy. Even more dangerous is that, through misunderstanding or malicious provocations, the shared heritage that should bring people closer might be turned into a tool of conflict and hostility, acting against its intended purpose. This is especially concerning as, in this region, the change of names, the erasure of script and language, the severing of direct connections, and various forms of poverty and deprivation have created fertile ground for the growth of different kinds of fundamentalism.

The history of Iranian art is a vast field where the interpretation of each part is made possible through attention to the reflection of meanings in multiple works and by tracing them through preceding and subsequent periods. Therefore, scholarly work requires attention to what we have called the “fourth layer,” 16 which refers to the functions and contexts that connect and relate each school of thought to others. Through historical discontinuities, themes and their manifestations have been continually renewed; sometimes an ancient theme reappears in new forms, while at other times, old forms carry new meanings. These overlapping layers have enriched both form and meaning. Understanding how these connections work is only possible by considering long time spans.

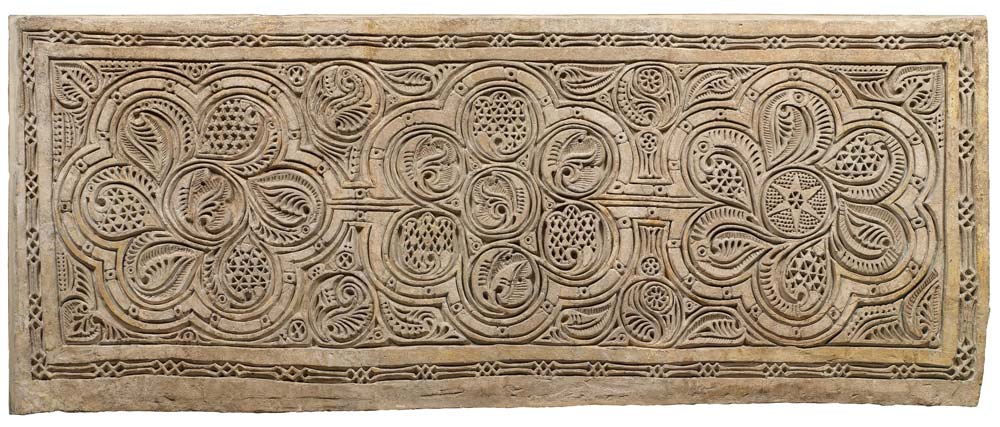

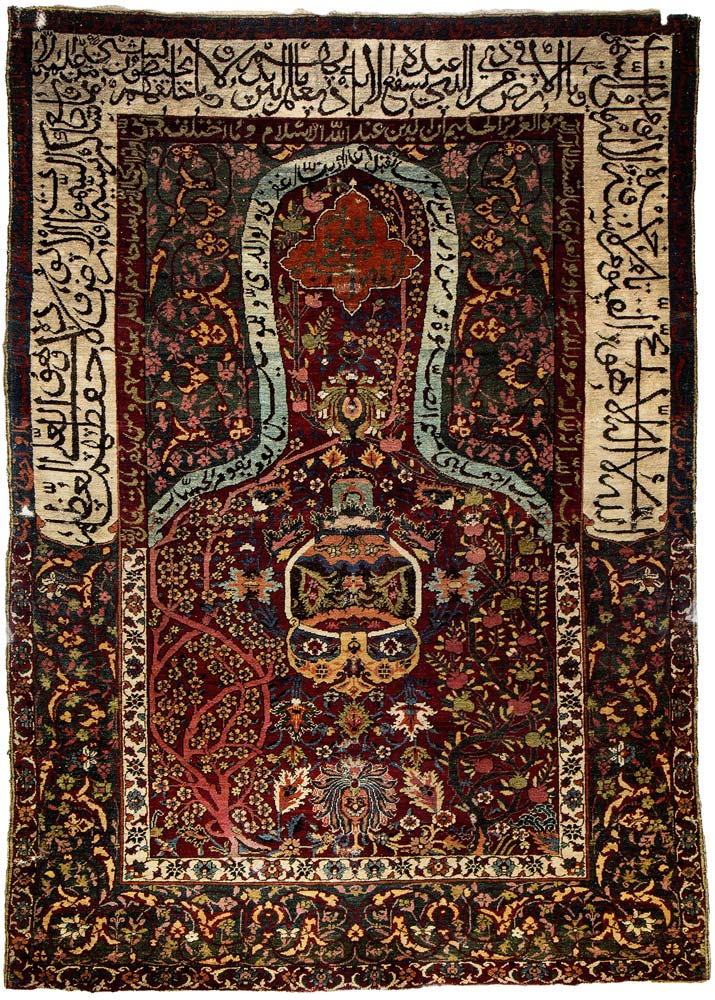

For example, in the tenth lecture, we referred to the motif of the “pearl” and the “oyster,” which, in the Persian school, emerged in a novel way, backed by the accumulation of older meanings. This motif then repeatedly appeared in the designs of the Parthian school in a more developed form. Later, during the period we call the Renaissance of Iranian art and culture—namely, the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries CE—it was revived again in new forms, particularly in Persian literature and poetry.

If researchers study these layers in isolation or view a period of this history as detached from its past under the label of “Islamic art,” the understanding of this chain of meaning will be entirely out of reach.

Orientalist scholarship, in studying the history of Iranian art, often divides periods into pre-Islamic and post-Islamic eras. This division, influenced more by the intellectual framework of Orientalists than by a study of Iran’s historical materials, has obscured the continuous flow of this history. One of the consequences of this is that the Renaissance of Iranian art and culture in the 9th and 10th centuries CE (3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries AH), which flourished based on the legacy of this culture’s past, becomes distorted. The researcher, either by accepting this division, focuses on explaining scattered elements under the label of “Islamic art,” where the connections are severed, or, conversely, the researcher’s efforts are mobilized in a stance against the Orientalist perspective, which ultimately results in something similar to the “oppressed East” stance of Edward Said.

It is evident that in naming historical periods, attention must be paid to the most crucial factors that have played a role in the transformation of consciousness. However, it is also important to recognize that the influence of key factors in shaping each cultural identity differs. For example, the broad application of “religion” as a defining factor across different cultural areas is meaningless; while in one society, religion might be the best criterion for organizing a meaningful classification and naming periods, in another, prioritizing religious changes might obscure the understanding of ongoing connections.

Every historian must necessarily limit their work to a specific period in history. However, the continuity in the long history of this land necessitates that any theoretical work consider the connections between different historical periods of Iran. No period begins in isolation, and a historian cannot write the history of one period without considering the preceding period. This principle is especially relevant to two groups: historians of ancient times and those of contemporary Iran.

One of the most significant features of Iranian culture that engages every historian, regardless of the specific period they focus on, is the long-standing continuity of this culture. To understand this historical continuity, we need concepts that can explain the history of Iran from within.

Although Iranshahr is an ancient term used to denote a territorial domain, Dr. Tabatabai uses it in his explanation as a thread that connects different historical periods of Iran and demonstrates the continuity of its fundamental idea.

The question is: Can the term Islamic Art as a general category in the global art history division hold a proper place? It seems that some European historians have labeled the emerging civilizations, from Andalusia and North Africa to the borders of China, as “Islamic” based on their own Christian-centric model.

In this model, desert-dwelling peoples, relying on a new interpretation of ancient cultures, have created a new civilization by blending Iranian and Byzantine art. 17

Here, it is important to note the differences between the terms Islamic Era, Islamic Civilization, and Islamic Art. Some recent research reveals insights about Islamic Civilization; 18 for example, it is noted that the term Islam began appearing in documents from the mid-3rd century AH. 19 This period coincides with the flourishing or renaissance of Iranian art and culture, continuing from its earlier times, which we will refer to as the Parthian and Khurasani School in forthcoming lectures. This school had a significant influence on the Iranian world and surrounding regions, including what has been termed Islamic Civilization.

Here, it must be asked whether merely the political changes and the gradual conquest of Iranian lands can be considered a turning point in the history of Iranian art. To what extent does such periodization align with the transformations within the system of Iranian art? And was it not this system of Iranian art that infused its essence into what later developed into Islamic Civilization? While such terminology might be effective and clarifying for cultures that were transformed by the process of unifying the Islamic realm or that emerged altogether, does it not obscure the understanding of Iranian culture? And does it not distort its role in shaping Islamic civilization? 20

It is noteworthy that some scholars of Islam, including Corbin and Henri Massé, have argued that Islamic theology emerged from a tradition of discourse and that its delicate spirit was derived from Iranian culture.

From an internal perspective, gradual but significant changes did indeed occur, as Islamic Civilization facilitated a greater amalgamation of Iranian culture with its ancient essence. It should be noted that ancient culture did not suddenly enter Iran through Islam; rather, there was a long and extensive history of interaction and mutual influence with Mesopotamia, Egypt, Abyssinia, Yemen, as well as through the hosting of Judaism, Christianity, and earlier Gnostic tendencies. However, at this stage, a new synthesis emerged, which Henri Corbin refers to as Iranian Islam.

Corbin, in his work History of Philosophy in Islam, points out that rather than viewing this phase of philosophical history as belonging to Arab culture, as some historians might prefer, we should consider this philosophical achievement as entirely Iranian from start to finish. Philosophers such as Farabi, Avicenna, Suhrawardi, and Sadr al-Din Shirazi, as well as later figures like Rajabali Tabatabai and Hajj Mulla Hadi Sabzevari, were Iranian and developed within the context of Iranian thought and culture.

Using the term Medieval to refer to historical periods in Iran that are contemporaneous with the European Middle Ages is problematic. It merely creates a chronological slice for the purpose of aligning different histories, without any meaningful connection to the historical materials of Iran.

One must ask how applying this periodization or using this term relates to the transformation of the history of art and culture in the Iranian world. If we accept this term as a new construct for understanding history, what two meaningful periods of Iranian history do these “Middle Ages” lie between?

Notably, a portion of this European Middle Ages, including the 3rd and 4th centuries AH, coincides with the Renaissance or peak of Iranian art and culture.

On the other hand, in the lands under the sway of Islamic Civilization, it was only in Iran that continuous efforts were made to establish national states. Therefore, Tabatabai argues that, despite accepting Islam, Iranians remained outside the world of the Islamic Caliphate.

Understanding the relationship between religion and culture in Iranian thought is crucial here and will aid in comprehending this complexity: Religion has always been a part of the broader Iranian culture, but Iranian culture was not limited to or defined by religion. The continuity of Iran, in ancient times, was the continuity of this comprehensive and rational culture. In all three ancient historical periods, religion was a part of Iranian culture, and in each period, it contributed to a unique and innovative synthesis.

Thus, in the context of Iranian culture, labeling arts as Islamic, Zoroastrian, Manichaean, Buddhist, and so on, or periodizing based on these labels, creates inconsistencies with other dimensions of this culture.

“In the geographical conditions of Iran, no appearance has existed that does not have a complex internal manifestation. Therefore, the history of Iran cannot be written merely as a history of visible territorial changes. The history of the Iranian land is fundamentally the history of Iranian thought, or in other words, the history of the continuities of action and thought. This means that no historical event exists that is not intertwined with thought and has not gained a new determination through thought. This determination is never simple; it is always complex, as the infusion of the monster of thought into the material of historical events turns it into such a complex occurrence that it can only be explained within a framework of intricate concepts.”

An effective periodization of the history of art and culture in Iran, like any thematic history in any culture, cannot be divorced from its general history. The researcher needs to integrate technical achievements, innovations, knowledge, a fundamental attention to the evolution of thought, as well as the rise and fall of key cities and the transfer and rupture of experiences among them.

The primacy of “nation” over “state”

In studying the historical materials of Iran, one of the crucial questions is how cultural continuity has been possible in the absence of national states. This question is completely irrelevant under theories established in other cultural centers. Therefore, the only way to address it is to refer to the historical nature of the place where this question arises, namely Iran. Tabatabai notes that, according to the logic of historical developments, nations typically emerge after the formation of states; that is, a nation is born through the acceptance of a social contract that results from the establishment of a State and Government (Nation = nasia = birth). However, the course of historical developments in Iran has differed from this usual pattern.

In previous lectures, we briefly discussed that the “nation” of Iran was initially established within its “culture,” and it was these shared cultural traits that transformed “diverse peoples” into a “cultural nation” over an extended period. The establishment of state/power emerged in a subsequent phase, meaning that the cultural nation of Iran existed prior to the state, and its emergence was not a result of state formation. This distinct relationship also led to a different historical behavior; throughout history, national bonds have endured despite the fall of central states, and new states have arisen on this resilient foundation. Even with the complete occupation of its territory, the cultural nation of Iran was not entirely absorbed or dissolved into the conquerors’ nation-states. For example, the Islamic Caliphate absorbed ancient lands like Egypt and Syria, but despite accepting the new religion, Iran did not dissolve into the Caliphate. Instead, it not only retained its national language but also entered a significant period of linguistic transformation, during which Modern Persian emerged and flourished.

Linguistic, Ethnic, and Religious Diversity and the Integration of Texts

Addressing the topic of language, or more accurately, “languages,” within the realm of Iranian culture through the lens of what is classified under the “Indo-European” language family in Europe-centered studies can be misleading.

The antiquity of the “national language” within the cultural realm of Iran is significant and noteworthy. The long history of the Persian language is classified into three major periods: Old Persian, Middle Persian (Parthian and Sassanian), and New Persian. However, it is important to note that the language has never been confined solely to Persian: a substantial part of our intellectual heritage has been written in other languages, including Classical Arabic, Syriac, and others.

Furthermore, the languages spoken across the geographical expanse of cultural Iran, such as in Armenia and Georgia, have been highly diverse, with regions even having literary traditions outside of a shared language family, such as the written heritage of Sogdian.

In Iran, throughout nearly all historical periods, a tradition of multilingualism in the writing of documents has been prevalent. During the Achaemenid Empire, inscriptions were made in Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian, and even occasionally in hieroglyphs. In the Parthian period, Middle Persian (Parthian), Greek, and sometimes Latin were used. During the Sassanian Empire, documents were written in Middle Persian (Sassanian Pahlavi), Latin, and Syriac. After the advent of Islam, New Persian, Arabic, and Syriac were utilized, and in the modern era, Persian, Arabic, and French languages were in use.

In European history, the establishment of the “Holy Roman Empire” preceded the formation of nation-states. Therefore, the collapse of this empire created a significant rupture, after which European peoples gradually, for the first time, began to establish independent nation-states.

It is essential to recognize that this model is in no way applicable to the history of Iran and its relationship with the Islamic Caliphate.

The same diversity and multiplicity can be seen in the realm of religion. Contrary to the European tradition, where the acceptance of a new religion often signified the end of the previous one and where every new scripture was considered to invalidate the preceding texts, leading to a lack of religious tolerance and, historically, no simultaneous acceptance of multiple official religions, in the world of Iranian culture, the coexistence and simultaneous acceptance of multiple religions has been a natural process. Buddhism in Khorasan in the eastern part of the Iranian world coexisted with Christianity in the western territories, alongside Zoroastrianism, as well as smaller communities such as Jews and Mandaeans, all of which were simultaneously accepted and had official status in the prevailing laws.

In general, Iranian culture has a hybrid nature, where various distinct characteristics have fused over a long history. This means that, in addition to the Iranian identity we refer to, Greek thought, ancient Islamic thought, and later modernity or contemporary texts have all blended into Iranian culture.

It should be noted that the Iranian identity has a historical legacy in Iran that spans its entire history and manifests itself within a complex and multifaceted culture. This means it is reflected not only in language but also in religion, rituals, interpretations based on national culture, epic thought, modular art designs, music, and architectural space design.

Ethnicity, Art, Love

The aim of drawing readers’ attention to the diversity in religion, languages, and intellectual texts is, at a higher level, to highlight a culture where “unity” is established at a more profound layer. Primarily, the foundation of such a system is not based on religious, linguistic, or ethnic unity.

At the beginning of the development of Iranian culture, during the formation of agrarian life, the element of creation and fertility held a unique position in the intellectual system. One of the ancient manifestations of a “perpetually present, immortal, and eternal” creative force in Iranian mythology is the figure of Sena or Simurgh. The result of this perspective on the world is the reverence for “soul.”

In their historical evolution, people have gradually achieved a unity that has been established without dismissing internal diversity, emerging from shared ethnic achievements, memories, and lived experiences. This unity is reflected in languages where the concept of “Race” does not have a place. Although the European term “Race” is translated into Persian as “نژاد” (nejād), what we find in Persian heritage significantly differs from its Latin equivalent. 21 In foundational texts, the attribute “نژادگی” (nezhādegī) conveys meanings related to virtuous capabilities, behavior, righteous conduct, and integrity—qualities acquired not through hereditary bloodlines but through cultural inheritance, effort, and character. This concept is, in fact, connected to the broader meaning of the term “art” (from Persian “ho” + “nar” = virtuous capability). As the wise poet Ferdowsi states:

‘How could art exist without gem? / Have you seen someone of noble lineage without art?’

In other words, both artistry and nobility are considered prerequisites for one another.

The Church of Ctesiphon was one of the major branches of Christianity in the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

In the world of Iranian culture, the simultaneity and coexistence of multiple religions has historically been a natural process. Buddhism in Khorasan in the eastern part of the Iranian world, alongside Christianity in the western regions, Zoroastrianism, and smaller communities such as Jews and Mandaeans, all existed concurrently and were recognized in legal and social interactions.

According to Dr. Tabatabai, the relationship between “religion” and “culture” is such that: Religion can serve as the foundation for the creation of a community, but the birth of a nation requires culture. In this sense, a nation is not defined solely by religion; rather, it emerges around a culture of which religion is also a part.

“Art” conveys an important value in Iranian culture, intricately linked to the themes of love, sovereignty, and transcendence. As expressed by Hafez:

“There is a hidden subtlety from which love arises,

Not from the lips, the ruby, or the line of the brow.

The beauty of a person is not just the eye, the face, or the mole;

There are a thousand nuances in this matter of devotion.

Those who follow the path do not buy the silk robe

From someone devoid of ‘art.’

Reaching your threshold is indeed difficult;

Ascending to the heights of sovereignty is fraught with challenges.”

In the study of the history of Iranian culture and the art of Iranian peoples, basing theories on the concept of the “Aryan race” and consequently organizing periods according to the arrival of Aryan tribes into this land not only fundamentally contradicts the ethnic diversity in the cultural world of Iran, but also creates insurmountable obstacles in research.

In the majority of Iranian romantic epics, heroes of high virtue have devoted their hearts to foreign lovers. In the Parthian romances, such as those of Zal and Rudabeh, Bijan and Manijeh, and Khosrow and Shirin, all the women, according to the contemporary use of the term “race,” come from different races. However, this concept generally has no bearing in these stories.

From this perspective, particularly concerning the explanation of the history of Iranian culture and the art of Iranian peoples, basing theories on the concept of the “Aryan race” and classifications that depend on the presence or absence of Aryan tribes creates insurmountable obstacles in research. It should be noted that the validity of the Aryan race theory and its attribution to Iranian civilizations is seriously questioned both from a genetic standpoint and by some competing theories. 22

Thus, emphasizing racial origins and inflating blood relations, in accordance with some Germanic theories and legal discussions developed by the German and French schools, can be misleading.

Similarly, there should be skepticism about new nomenclatures based on ethnic divisions. The concept of “ethnicity,” as used by Europeans in its modern sense, became prominent in Orientalist studies of Iran. Today, this method of categorization based on ethnic groups is still repeated in the descriptions of some major world museums, which has many issues.

In the Iranian Plateau, each archaeological mound typically has multiple layers or “strata,” which may belong to different groups or ethnicities that have moved or changed over long periods. In contrast, researchers in Europe rarely face such complex stratigraphy in their archaeological sites. For instance, in Germanic regions, experts usually deal with a single layer, often Roman in origin. Consequently, naming artistic schools and styles and attributing them to ethnic groups in Europe is relatively straightforward. For example, one can easily label a style as “Gothic” and attribute it to the Goths and Visigoths, explaining a style in architecture during the rule of the Capetians. Such ethnic naming effectively clarifies the association of a style.

From this perspective, the use of certain modern sciences, such as anthropology, before these disciplines have established their legitimacy in our understanding, will pose a fundamental obstacle to knowledge. The foundation of anthropological studies in Europe was initially closely aligned with the division of racial and environmental categories. Conducting anthropological work on the inhabitants of Iranian lands, without considering the extensive historical periods and the interrelations and blending of different ethnic groups, is not straightforward.

For example, we do not precisely know when and for what reasons the Baloch people settled in the area now known as Balochistan. The linguistic relationship between the Balochi language and the languages of northwestern Iran, particularly its proximity to the Tati language, is among the questions that remain unanswered. Consequently, it remains unclear whether the extensive archaeological sites in the region extending to Makran and Mauryan date back to a time earlier than the settlement of the Baloch tribes or if they are from a later period. It is difficult to determine which groups or so-called tribes of the Iranian people are associated with the multiple layers of the Burnt City in Zabol and the Aratta civilization in Kerman. Moreover, it is uncertain how essential and beneficial it is to pursue such questions when explaining the intertwined culture that emerged from the contributions of these tribes. 23

From the perspective of Orientalists, the role of the Arabic language as the language of science in Islamic civilization is often compared to the role of Latin in Christian Europe. Although this kind of comparison between different historical contexts is generally unilluminating, it is important to acknowledge the significant contribution of Iranian scholars in shaping the eloquence and grammar of the Arabic language. The foundation of eloquence, syntax, and lexicography in the Nizamiyah institutions was influenced by the establishment of these sciences by early Iranian scholars. Up until the 6th and 7th centuries AH, students of jurisprudence, theology, and philosophy first learned Arabic in the schools of Shiraz. Moreover, the vast repository of literary texts, historical sources, wisdom, philosophy, and scientific works in Arabic, created by Iranian translators and scholars, enriched the language significantly. However, Arabic served as the language of science in Iran, not as the language of the Iranian family; Persian became the language of poetry and culture.

In the cultural sphere of Europe, prior to the modern era, the characteristic of multilingualism in historical, political, and cultural communications was not experienced. Unlike the nearly universal inscriptions of ancient Iran and the later writing traditions, where documents were commonly composed in multiple languages or used several languages in different texts, there are no historical European documents (except for the Rosetta Stone related to the conquest of Egypt) that are bilingual or multilingual.

For scholarly work on this topic, it is crucial to consistently consider that the source of Iranian culture and thought has never been confined to a single intellectual tradition; this is a fundamental characteristic of Iranian culture. Understanding the different texts, which at times coexist simultaneously and at other times layer upon each other with varying degrees of precedence, is essential for grasping the historical materials of Iran. The primary texts can be categorized as “Iranian”, “Iranian-Greek”, “Iranian-Antique”, and more recently “Modernity”. Among these, the Iranian cultural and intellectual tradition has remained a continuous thread in the thought, culture, and art of Iran.

It is evident that from a European perspective, with its distinct intellectual tradition, comprehending Iranian culture and recognizing it as a foundational system with a hybrid nature—characterized by its openness to diverse texts—can be significantly challenging.

Tradition

The problem regarding the explanation of periods in the history of Iranian art and culture also manifests under the field of sociology. Dr. Tabatabai correctly points out that although social sciences are generally part of modernity, in a state of intellectual denial where the nature of the connection with tradition is unclear, and tradition stands as a rigid barrier against any revision of its foundations, the application of sociological methods has not only failed to resolve issues but has also created new problems. It is conceivable that the connection between modern social sciences and a rigid tradition has resulted in the creation of “ideological” rather than “scientific” constructs. Thus, the discussion of the dichotomy of “tradition and modernity” in explaining the art of modern Iran emerged from a sociological perspective. However, examining one side of this dichotomy (i.e., “tradition” or “modernity”) without the other is not feasible. Therefore, the crisis of modernity, despite the recent century-long efforts, is undoubtedly a crisis in the foundations of rational thought in the recent centuries of Iran’s history or a crisis of the rigidity of “tradition.”

The issue of translating the potentially misleading term “سنت” (tradition) into the Latin “Tradition” and its contemporary usage has significant implications. “Tradition” is a fundamental concept in European Christianity, deeply connected with the history of Christian theological developments and has acquired unprecedented expansion. Christian tradition represents a continuum that continues alongside history and is embedded within it.

In contrast, in Islamic sciences, particularly in the principles of jurisprudence, “سنت” (Sunna) refers to one of the four sources of law and denotes the sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad. In Sunni Islam, the Sunna is confined to the Prophet and his companions, while in Shia Islam, it extends to the Imams. Thus, in this context, “سنت” refers to a set of practices with a historical endpoint, differing significantly from its European counterpart in this respect.

With this explanation, it remains unclear how the illusion of a “traditional art” has emerged and what materials and periods this term refers to. This designation preemptively implies an art form belonging to the past, which cannot be renewed. In our language, the label “traditional” turns this art into an immutable and exotic text, created by mechanisms different from rational logic. In practice, it justifies the rigidity, stagnation, nostalgia, and passivity associated with it.

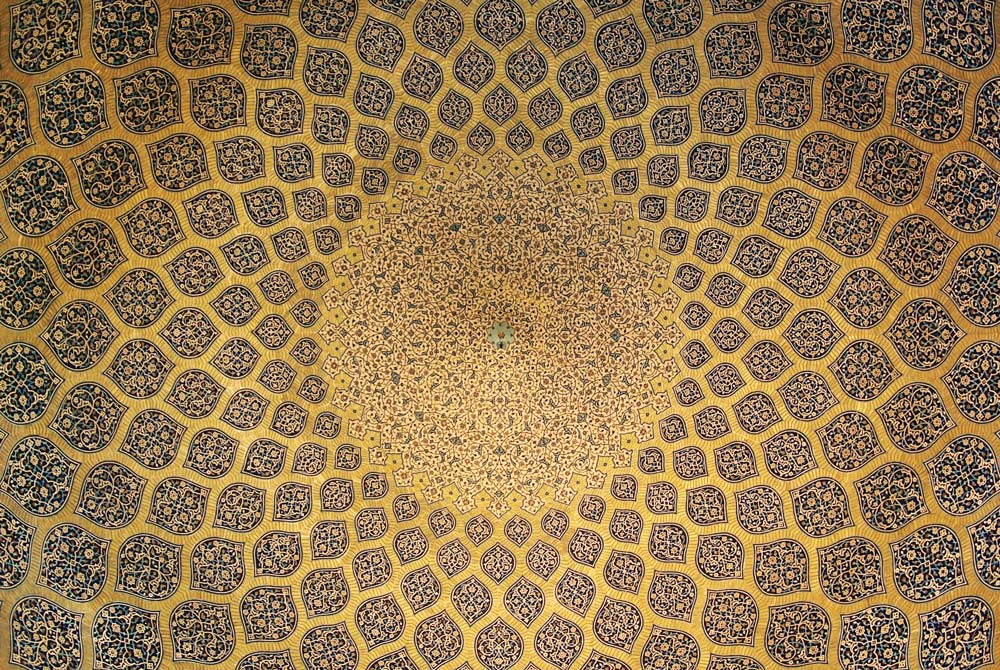

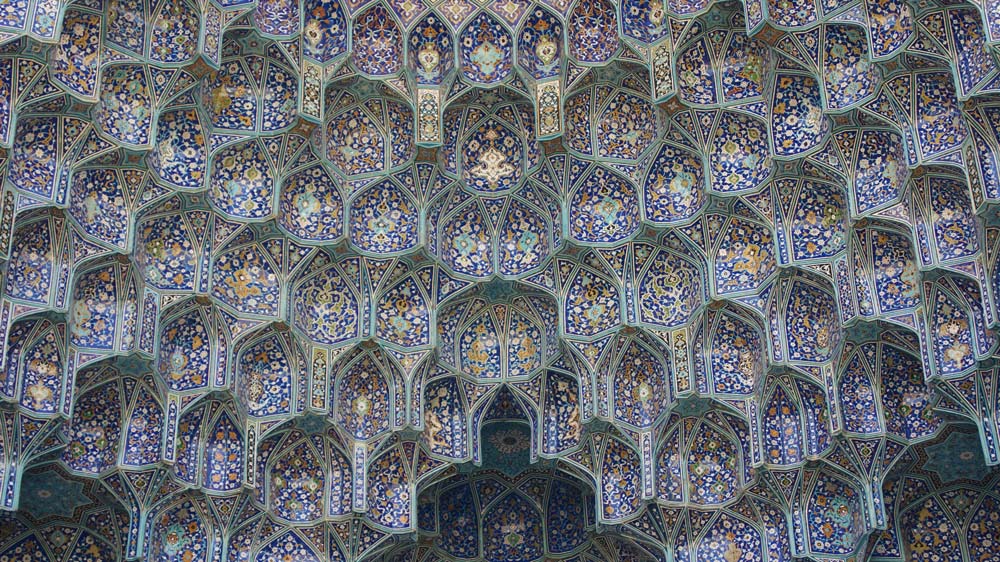

The design of the pattern beneath the dome, both in its form and its reference to the peacock, one of the representations of the Simurgh, exceptionally embodies the experience of unity and multiplicity.

The aim of discussing the diversity in religions, languages, ethnicities, and intellectual texts is to highlight a culture where “unity” is established at a deeper layer. Fundamentally, such a system is not based on religious, linguistic, ethnic, or blood unity. Here, unity is not achieved through purity or uniformity but through the acceptance of diversity and the synergistic creation of a shared cultural foundation.

The Role of Geography in Ancient Iranian Naming Conventions

Considering the naming conventions used by the ancients can be enlightening, as they often provide insights into deeper meanings and relationships between matters that might be obscure to us today.

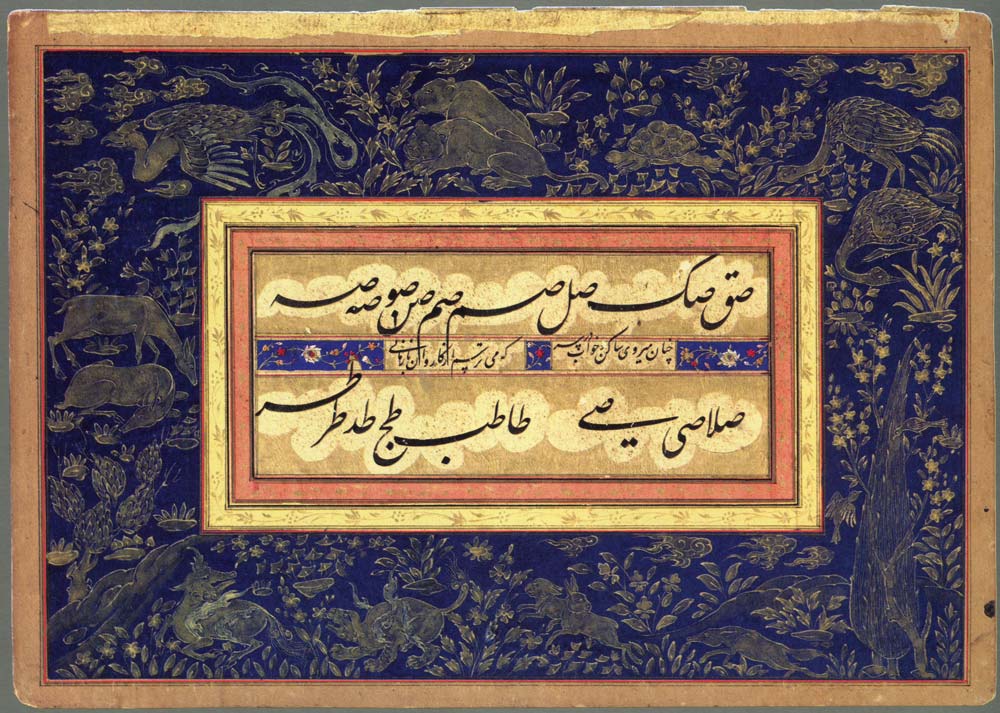

For example, in our visual art, a category of motifs has traditionally been referred to as “Gereft-o-Gir” (grasp and capture). This name points to the connection between these motifs and fundamental themes in the history of thought, and guides us to the development and evolution of a very ancient thematic thread. Some Orientalists, however, have classified these motifs under “animal ornaments” and placed them alongside another category known as “plant ornaments.” The latter group, “plant ornaments,” includes some of the most significant motifs in Iranian art that embody this culture’s understanding of the “creative principle.”

Seemingly straightforward classifications, which are based on visible descriptions, can sometimes, due to a lack of deep familiarity, obscure the deeper layers of meaning, divert researchers from core issues, and alter the significance and position of subjects.

By referring to historical naming conventions, or those established by scholars of previous generations in fields like literary history, architectural history, and political thought, it appears that the spirit of Iranian culture was predominantly conveyed through names of “geographical locations,” such as the Khorasani school or the Azerbaijani style. These names do not imply that the creation of a school or style was solely the work of the local inhabitants of a particular region. Instead, the selection of these names reflects the ancients’ and cultural leaders’ understanding of the ebb and flow of “history” within the “geography” of Iran. Throughout the historical evolution of thought and culture, the achievements of this nation have repeatedly focused on a center, which served as a nurturing ground for the shared idea and common aesthetic content. Over a long period, new schools or eras emerged based on these previous shared achievements. Thus, various achievements throughout different historical periods became associated with the names of cities and villages. There exists a long sequence of place names that have become iconic for specific eras, styles, and methodologies.

The Relationship between the Establishment of Power and the Establishment in Art and Culture

Naming schools or periods of art based on dynasties of power and political systems is a method commonly observed in both European historical tradition and the historical tradition of the Far East. For instance, historical periods of Chinese art have been named according to the ruling dynasties, such as the Tang, Ming, and Song dynasties, which are significant periods in Chinese history.

This pattern is also evident in the cultural satellites influenced by China, such as Japan. For example, periods in Japanese art history are similarly named after significant dynasties or ruling periods. 24

In European art history as well, naming conventions, even from ancient times and early scattered civilizations, have often been based on the names of ruling dynasties. This practice underscores the connection between the political power structures and the categorization of cultural and artistic periods. 25

In Iran, the practice of naming art schools and styles after kings or dynasties does not have a historical precedent or support in ancient works and documents. However, this method has been extensively used by European researchers in studying Iranian art in modern times. Examples include names such as Elamite Art, Achaemenid Art, Sassanian Art, Abbasid Art, Seljuk Art, Mongol Art, and Timurid Art, all of which are modern inventions. These designations can potentially distort the relationships between “state” and “cultural nation” in Iran, as previously mentioned, and may present a reversed view of the establishment of state and nation within the context of Iranian culture.

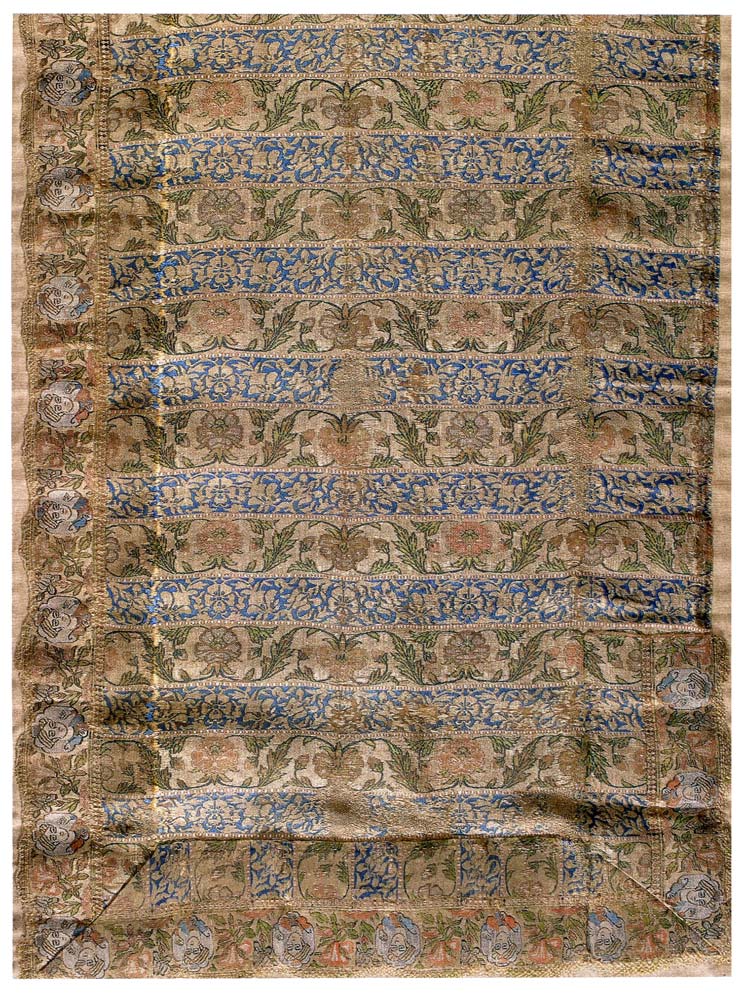

One of the fundamental values of this shared culture is the reverence for the “soul.” From the beginning of the formation of Iranian culture, during the period of agrarian life, the concept of birth and fertility gained an unparalleled status and gradually manifested in a multitude of forms within the culture.

In ancient Iranian mythology, one of the manifestations of the “eternal, ever-present, life-giving essence” is the Sena or Simurgh, which nests in the Tree of Life or Tree of Bliss and is guarded by its pairs of protectors. Over time, these earlier simple representations evolved into more complex forms, yet they still embody the core concepts of fertility, immortality, and the relationship between unity and multiplicity.

Origins of Art History

One of the most significant breaks in Iranian intellectual history is the transition from mythological belief, marking a meaningful turning point and the beginning of an important era in the cultural life of Iran. This transition, from various perspectives, is relevant across a range of thematic histories.

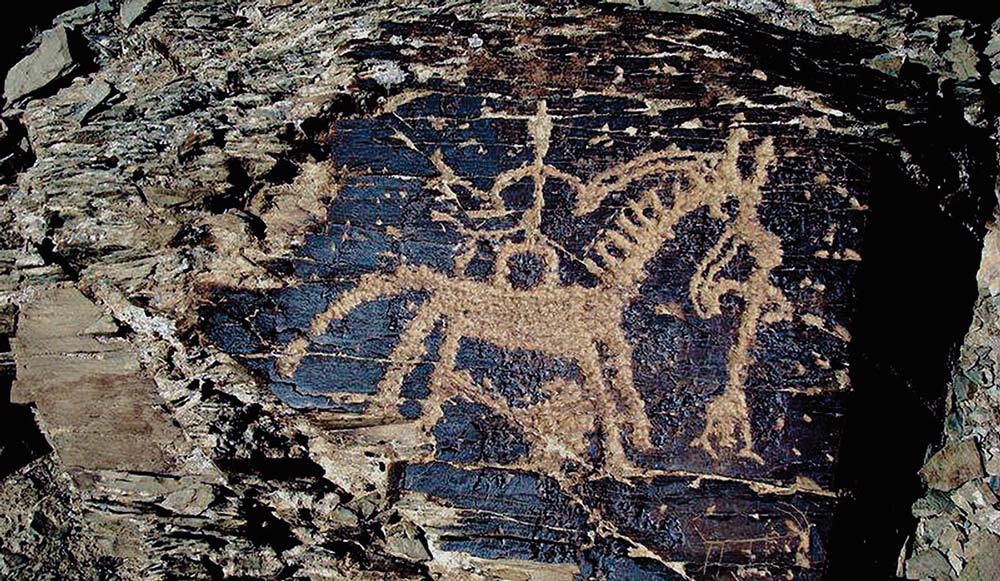

In contrast, the common classifications based on the break between “prehistory” and “history,” which rely on the concept of a “magical age,” are not illuminating for studying the history of Iran. As mentioned, merely attempting to align existing examples from this culture with European historiographical models yields little result. While it may be relatively easy to find Iranian counterparts to examples from European art history—such as finding numerous examples in the Iranian plateau similar to the cave paintings of Altamira or Lascaux, including those in the Mirmalas cave in Lorestan or even more extensively in eastern Iran with over five thousand known motifs and carvings—this alignment does not necessarily contribute to a meaningful understanding. These motifs are worth studying in their own context, but simply fitting them into a European historiographical framework is not effective.

The “Age of Formation” in the Iranian world has a lengthy chronology, approximately three times the length of all the historical periods that followed up to the present day. As discussed in previous articles, the initial steps of this culture’s formation include the Cosmic Art and Mythological Art periods, characterized by the appearance of cave paintings and the erection of menhirs. These developments led to the emergence of the “poetic human” and the cultivation of languages as vessels for thought. The result of these extensive millennia was the establishment of settled life and the development of agricultural communities, from which the first school of Iranian art was born.