An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

The soul has the motivation to know and desires to see itself; the longing for awareness is the very essence of the human soul.

In the previous lectures, depending on the topic, we discussed the manifestations of various forms of knowledge that emerged in each cultural center. Now, we will focus on another aspect: each culture’s definition of the journey of the soul’s ascent, or the path to human perfection and salvation. Like other cultural manifestations, the understanding of “the journey of perfection” has taken on different forms depending on the relationship between humans, existence, and time as understood in each context. A culture’s perception of the possibility of the soul’s growth is significant because it forms the core that generates meaning in life, influencing the way of living, ethics, customs, and art. It is particularly important to consider the relationship between this meaning and the idea of “establishment” and the legitimacy of the system of power.

The narrative framework of the “Hero’s Journey” is one of the oldest and most universal story templates shared across cultures. These stories have the capacity not only to convey the experiences of the challenges of migration and travel but also to serve as allegories for the soul’s insights and inner revelations that propel a person from one state to another. Despite a common overarching structure, there is a diversity in these stories that subtly reveals the forms of consciousness that distinguish each culture from the others. Beyond this, examining rituals of initiation or various spiritual practices can also bring us closer to understanding the cultural differences in perceiving this theme.

The narrative framework of the “Hero’s Journey,” one of the oldest and most universal storytelling patterns, tells the tale of traversing difficult paths, overcoming arduous trials, and navigating the stages of a challenging journey. These stories have the capacity to not only recount the hero’s struggle for survival and quest but also to serve as allegories for the soul’s experiences and inner revelations that guide a person from one state to another.

To clarify this topic, we will compare details of the Hero’s Journey stories in Iranian culture with those in other cultures. We will then focus on a very ancient example of such stories that developed within Iranian culture: the “Hymn of the Pearl.” This valuable example is rich with meanings that are intricately woven into a single allegory. The evidence suggests the emergence of a new intellectual framework that uniquely transfers the functions of the heavens to the earth. This new awareness, encapsulated in the form of an allegorical narrative, spreads rapidly and easily. The organization of various aspects of social life around this narrative creates a foundation for the establishment of power, supported by a belief system. Identifying manifestations of this awareness in other forms of art and culture highlights the influence, expansion, and dissemination of a fundamental idea that is compactly presented within this narrative.

The Hero’s Journey Story

The “Hero’s Journey” is one of the oldest, and perhaps most universal, stories of humanity. Among various peoples and cultures, diverse narratives following the pattern of a hero’s arduous journey through various stages are prevalent. These stories recount the struggle against the natural challenges of the journey, the fight for survival, and ultimately, salvation. The outward form of these narratives may carry an experience as ancient as the departure of the earliest human ancestors from the African continent and their spread across the lands of the earth—migrations that are a part of our human experience and have been repeated in different ways up to the present day.

As explained in previous discussions, in the Golden Rectangle region, the spread of a lifestyle based on food cultivation, and its persistence despite repeated and scattered failures, eventually took root and expanded human capability for managing life. In large communities where settled life was possible, concepts such as salvation, eternal life, and the choice of one’s path were developed in greater detail. The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest examples of the Hero’s Journey pattern in such a context. In a version of this story that has survived from the Sumerian civilization, a journey is recounted that is not merely a physical journey but one in which meaning is achieved along the way. The condensed pattern of this story is as follows: the hero’s desire for immortality, breaking from the current state, journey, overcoming the hardships of the path, initiation, encounter, discovering the goal, attaining a new belief, returning to the homeland, and sharing new knowledge with those who have awaited the hero.

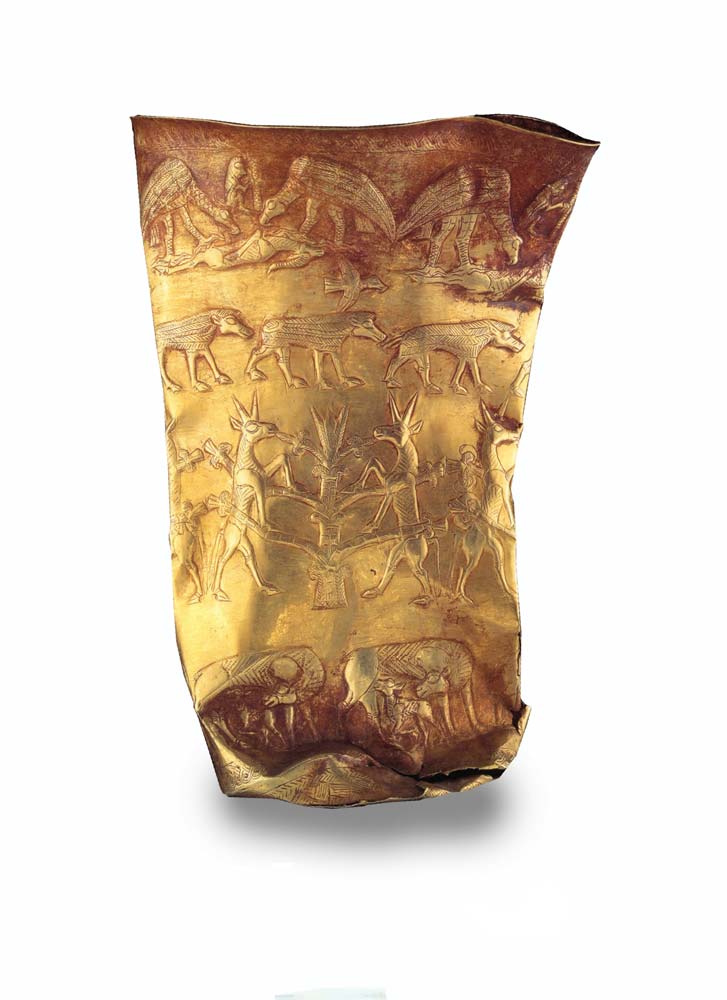

The theme of the journey of life is likely one of the oldest motifs that has preoccupied humanity. Perhaps one of the earliest forms of this concept is delicately depicted on the Golden Cup of Marlik, which illustrates the process of the growth and eventual decline of a goat—one of the first domesticated and beneficial animals in this region.

The idea, which evolves into the concept of “the journey of perfection” in more developed forms, is closely associated with the motif of “journey” in Iranian culture. One of the most famous examples of this is the story of the birds’ journey to the Simurgh in Attar’s Conference of the Birds (Mantiqu’t-Tayr). Whenever this meaning is intended, the narrative of the journey usually forms the backdrop of the story. For example, Zal, the child of light, travels to the Simurgh’s abode and returns as the leader of wise champions.

Most romantic stories also unfold during a journey, such as those of Zal and Rudabeh, Bijan and Manijeh, Rustam and Tahmineh, and Gushtasp and Katayoun. In Khosrow and Shirin, the story begins with a journey, and its lyrical conflicts are all intertwined with the theme of travel.

Another example is the account of the journey of the priest Ardawiraz to the world of the dead in the Ardawiraf Nama. 1 Perhaps the Four Journeys (Asfar-e Arba’ah) of Mulla Sadra Shirazi are among the latest examples of explaining the soul’s journey in Iranian philosophical thought, presented in the form of an allegorical journey.

It should be noted that the narrative pattern of the journey is not exclusive to settled societies and can even be found among isolated groups. For example, Aboriginal Australians maintain the story of their ancestors’ journeys through lengthy ceremonial walks. Similarly, among the Pacific Islanders, there is a prevalent story of a great sea voyage in search of an island of immortality.

On the other hand, many cultures continue to practice ceremonial journeys as part of spiritual purification, with rituals repeated periodically in the calendar. Some of these rituals commemorate a journey, others involve people undertaking the journey themselves, and yet others involve spectators observing the journey. For example, in Hinduism, the annual journey of Shiva—from the cosmic abode of Brahma to his home on the Himalayan peak—is celebrated. This journey, which includes his passage across the Ganges River from the mountains to the plains, is observed in the ritual of meeting the Ganges River and dedicating oneself to it.

Christian pilgrims, in memory of the early missionaries, walk on foot from the Pyrenees mountains in Spain to a monastery in France.

Even in broader contexts, the Christian calendar maintains a series of rituals throughout the year that commemorate the life of Jesus Christ—from his birth at Christmas, to the ascent of his spirit at Easter, and his return on the evening of Emmaus. These rituals honor the journey of God’s spirit in the human form of Christ, including his encounter with the sin-laden human, enduring sufferings, crucifixion, ascension, and the awaited return on the Day of Resurrection.

Through these stories, humanity has created symbols to explain its destiny and navigate the path of spiritual ascent, which, like other cultural manifestations, arise from the core of initial consciousness in each culture.

In Greek culture, with its “tragic” foundations, even in the narration of epic tales, sufferings are associated with the wrath of the gods and their ominous fates—gods who are directly involved in events. At the beginning of the Iliad, we see that the dispute among three goddesses over who is the most beautiful leads to the destruction of Troy. In this form of awareness, the devastating war of Troy is explained through the tragic fate of Paris, who is drawn into the journey and falls in love with the beautiful Helen.

In Iranian culture, which we described in the previous lecture as having an “epic” foundation, there is a world view where even misfortunes can be explained through a rational perspective.

In a world that Ferdowsi depicts through an allegory of the ancient peoples’ experience with agricultural life, every action today is akin to planting the seed of goodness or sowing the seeds of enmity and malice. The results of these actions will be reaped, whether by us or, undoubtedly, by our descendants:

“Whoever harbors evil thoughts / In the end, will meet with evil in their own body. The world should not be entrusted to evil / For the evil-doer will surely face evil. From all that you do, my son, beware / For time will bring no reward for malice.”

An Examination of the Hero’s Journey in Five Foundational Centers of Culture and Civilization

In the Indian subcontinent, Hindu culture is not based on the idea of human sovereignty. In this worldview, the rise and fall of the world are intertwined with the cosmic play of Brahma; thus, the Earth becomes a realm devoid of human spirit, suffering, and its remedy. From this perspective, Hindus essentially live within the framework of the journey of life. In this understanding of existence, human beings wander through a cycle of epochs, with colors and melodies within this culture, akin to the cycles of the Puranas, spinning the human spirit in its intricate rounds.

In Far Eastern culture, the spirit is a shadow of the ever-flowing Dao, immersed in a time that is neither beginning nor end, and is not concerned with ultimate conclusions. In a world that itself embodies the flow of the Dao, humans are in a maze of moments, continuously engaged in the process of “becoming.” They are travelers constantly on the brink of “nothingness” or “death,” and through awareness of this fleeting moment, they attend to each moment with care.

Here, “salvation” is achieved through the meditation of one’s presence in the moment between being and non-being, akin to the space between shadow and sunlight.

The oldest roots of ancient culture, found along the White Nile in Eritrea and Sudan, and the banks of the Blue Nile of the Pharaohs, are centered around the idea of the eternal cycle of reincarnation and the return of the Absolute Spirit in the form of the Pharaoh. Enormous efforts were devoted to the burial of this embodied eternity and the preparation for its return. This idea’s legacy continued in parts of Mesopotamia, where such a conception of humanity’s place in existence gradually nurtured an ethical essence, understanding salvation through adherence to religious commandments.

The concept of absolute sovereignty and the imposition of the Pharaoh’s will on the people continued in various forms within this culture. For example, it manifested as the dominance and rule of one ethnic group over others, a theme also present in the Old Testament narratives, such as the story of Jacob wrestling with Yahweh. In this covenant (Old Testament), it is agreed that the descendants of this prophet, the Israelites, would achieve supremacy and dominion over others, provided they followed Yahweh’s law.

In the Old Testament thinking, the Hero’s Journey is depicted in various stories, including Noah’s Ark and the splitting of the waters and the Exodus from Egypt. These stories intertwine with the concept of migration and leaving a place. Similarly, the idea of “salvation” in Abrahamic religions is closely associated with leaving a place and journeying to another world.

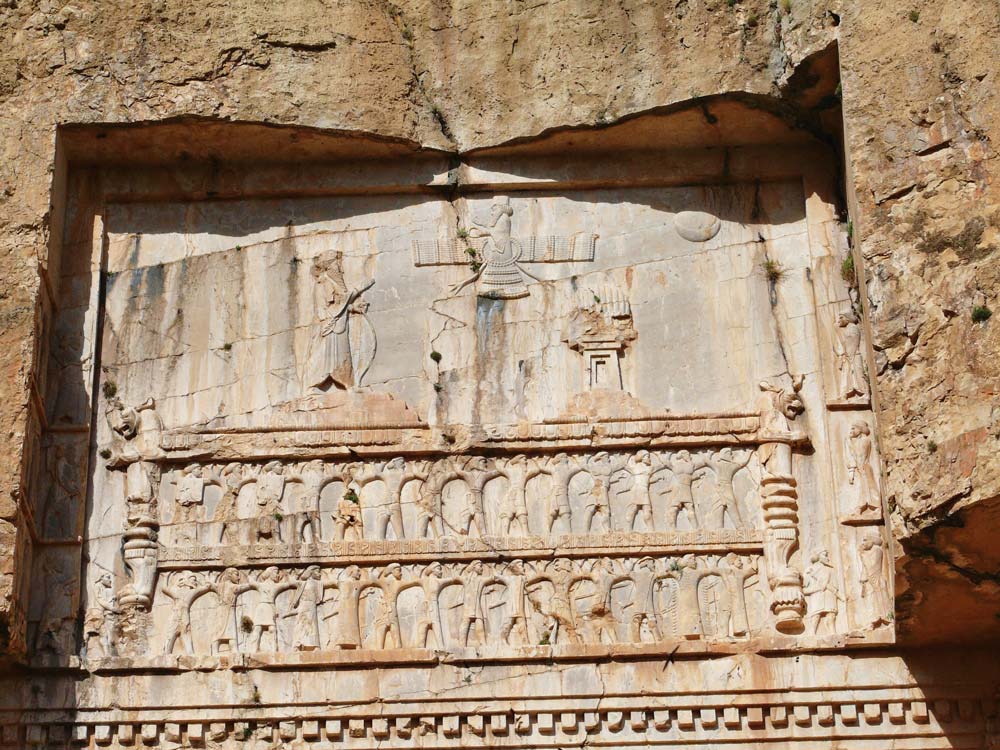

An older version of the idea that views humans as choosers between good and evil—where the consequences of such choices undoubtedly return to the individual—can be found in the inscription on the tomb of Darius the Great. This inscription serves as an epilogue to his journey through the seven realms and was written as a conclusion to this path. Beyond its historical significance, this text highlights the ancient influence of epic spirit, in the sense we are concerned with, in the political thought of this culture.

In part of this inscription, Darius, in his role as the wise king, speaks to future generations in the third person from his position of historical and legal authority:

“Darius the King says: By the will of Ahura Mazda, I am thus. I am a friend of goodness. I am not a friend of evil. I do not like to see the powerless being subjected to the power of force. I also do not like to see the subordinate suffer from the strong. What is right is what I favor. I am not a friend of liars. I am not vindictive. I am deeply averse to anything that angers me, and I am master over my own wrath. Whoever strives should be rewarded for their effort. Whoever errs should be punished for their sin. I do not like anyone to do harm to another, nor do I like evils to go unpunished. I do not believe what someone says about another unless it is accompanied by truthful evidence. What someone does for the benefit of others, to their utmost effort, I am pleased with that, and my pleasure in this is great and I derive joy from it.

This is my will and command. In what I have done, which you will see and hear, both in the homeland and on the battlefield, look at my wisdom. Look at my capability. As strong as my body is, I am also a skilled warrior. If my wisdom does not reveal whom to consider a friend or an enemy, then I think of his good deeds whether he is an enemy or a friend in my eyes. I am adept in both hands and feet. I am a good horseman, and in archery, I am swift whether on foot or on horseback. The abilities that Ahura Mazda has given me, and which I had the power to use, are given to me by Ahura Mazda. What I have done, I have done with these powers, and Ahura Mazda has granted them to me.”

In contrast, what we derive from the legacy of Greek art and culture is an effort to expand the order of the cosmos and transform it into a societal norm. In this culture, dialogue enters the political arena. Plato’s philosophy exemplifies the intellectual dimension of this awareness. The spirit of Greek culture is engaged in a grand struggle where not only human desires but also natural forces and external wills are involved. The attraction between the sexes or the conflict between natural desires and the will of the gods all culminate within the framework of fate; in other words, in this form of awareness, the soul is bound by destiny.

The social crisis in Greece is made evident by the death of Socrates. Greek philosophers sought to resolve this impasse through contemplation of the Other. Plato, in establishing the philosophy of metaphysics, looks to the ideas of the Magi to find a way out of this crisis.

In Iranian thought, the journey of the soul begins with the divine grace of farr (divine glory) bestowed upon the human-hero, and through a series of choices and battles throughout his life, it reaches its conclusion. Farr is the source of all good forces, and its continuous flow in the world extends hierarchically from Ahura Mazda to the Amesha Spentas and down to humanity. Ahura Mazda bestows farr upon those who are worthy, but this grace is neither constant nor infallible; it can be withdrawn due to poor choices made by individuals.

Despite the historical similarities between Iranian and Greek cultures, there are fundamental differences in their foundations that make each representative of distinct realms in terms of character, thought, and choice. To understand the difference in the essence of these two cultural hubs, comparing the story of the battle between the two Iranian heroes, Rustam and Esfandiar, with the Greek heroes Achilles and Hector can be illuminating.

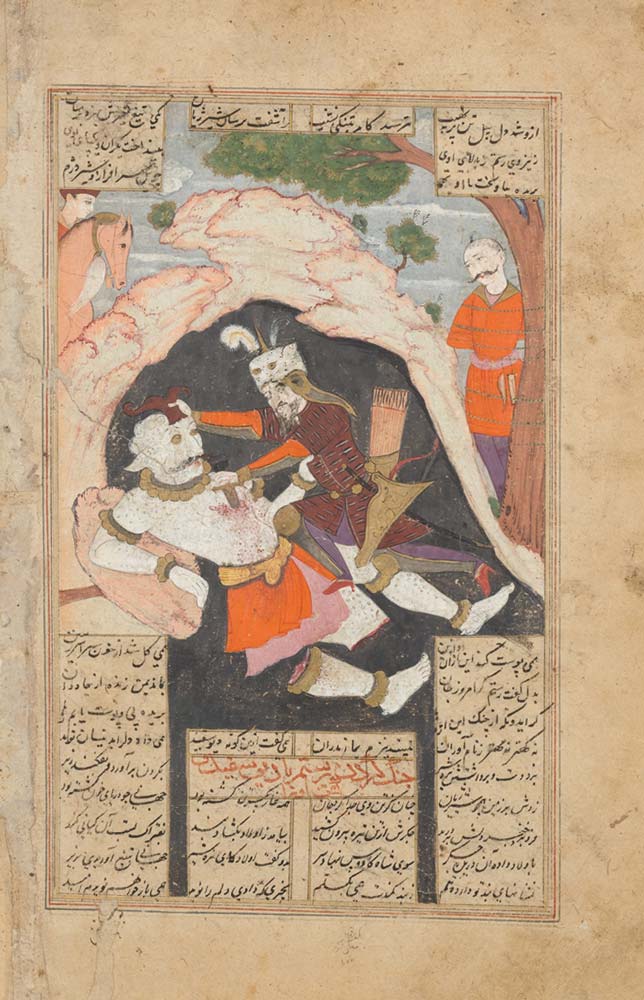

Both pairs are epic world-heroes, and they share notable similarities. Rustam and Hector are the foremost champions of their respective lands, while Esfandiar and Achilles are invulnerable and possess traits beyond mere physical strength. Esfandiar, a sacred hero, has only one point of vulnerability in his eye, and it is he who challenges Rustam to combat. The battle between Rustam and Esfandiar is not merely a conflict between two individuals but rather a clash between two ideologies and worldviews. Esfandiar, the sacred hero of the Zoroastrian faith, faces Rustam, the hero of the Dev Yasna or the Simurghian faith, representing the debate between two different beliefs. Before the battle, Rustam hosts Esfandiar in his own palace.

The story of Siyavash, the hero of Iranian epic history, begins with a journey: Giv and other heroes find a beautiful maiden in Turan, who will become the mother of Siyavash. As a child, Siyavash travels to Sistan, where he flourishes under the guidance of Rustam and learns the great principles of heroism from him. He safely passes the trial of purity and divine spirit set by the envious and vengeful Sudabeh. He then triumphs in a decisive battle against the Turanians, and when the enemy begs for mercy, contrary to his father Kay Kavus’s wishes, he pardons the enemy in accordance with the principles of chivalry. To honor his own soul, which embodies the delicate spirit of Iran, Siyavash chooses exile and never returns from this journey. Eventually, he is killed due to the jealousy of treacherous individuals. In this cultural context, Siyavash’s death is understood not as a tragic fate but as a heroic choice that immortalized his spirit and preserved his noble path. The story tells us that from Siyavash’s spilled blood, the Siyavashan plant grew, symbolizing the life and immortality of the illustrious hero.

Kay Khosrow, the son of Siyavash, represents the continuity of his existence and the enduring spirit of Iran. Goudarz dreams of Kay Khosrow and receives a divine whisper from Soroush that he is the future of Iran. In Goudarz’s dream, Kay Khosrow is sitting on a “stone” in a distant land. Goudarz sends his son, Giv, to find him. After a seven-year journey, Giv discovers Kay Khosrow in the mountains, sitting on a stone at sunset. The stone, embodying primordial radiance, is Kay Khosrow’s abode. Corbin notes that in this culture, one of the material forms of “farr” or divine glory is the stone. 2 Kay khosrow, together with Giv and his mother, Ferngis, crosses the Amu Darya after several battles and heads towards Iran.

Kay Khosrow is a king who, at the end of his reign, chooses to leave the world willingly. He returns to the mountains on a journey towards immortality and vanishes from the sight of heroes. In this story, Kay Khosrow is not only the king of Iran but also the “King of Time.” He is envisioned as the divine judge (Soshyant), the one who will bring about the final judgment, not after death in another realm, but here in this world amidst the trials of existence. 3 The anticipation of his return, as the “King of Time,” who will bring justice to the wrongdoers with the support of heroes, carries an ancient significance in this culture.

Rumi, using Kay Khosrow as an exemplar of the “Perfect Man” and employing the metaphor of the “moon’s journey” through the stages from crescent to full moon, has written:

“From journeys, the moon becomes Kay Khosrow; / Without journeys, how could the moon become Kay Khosrow?”

They embrace each other and speak words of wisdom: about lineage, nobility, and the path of righteousness. Rustam is willing to walk ahead of Esfandiar’s horse on foot to the king’s presence, but he cannot endure being bound, which he considers a disgrace. At the end of the battle, the holy Esfandiar dies in Rustam’s arms, and in his last breath, entrusts the care of his son Bahman to Rustam. Rustam then lays Esfandiar to rest in the tomb with the dignity befitting a great leader.

Achilles’ only weakness is his heel. He challenges Hector to a duel driven by his desire for vengeance for his young nephew; here, the blood relationship is the main motive— the entire Trojan War was sparked by the abduction of a beautiful woman. In Greek epic, Hector’s death is not due to his own choices but is explained by the role of fate (Moira).

Achilles ties Hector’s corpse to his chariot and drags it back to his tent. Hector’s father comes to plead with Achilles to return his son’s body. Here, the choice between good and evil and the concept of justice manifest during their conversation. Hector’s father reminds Achilles of the moral laws of the city (nomos), which justify the burial of his son according to the customs of honor.

In the Shahnameh, battles generally revolve around national ideals. Vengeances are not driven by personal blood relations but rather by the wrongful death of heroic figures such as Siyavash. In contrast, in the Iliad and the Odyssey, the conflict often centers around possession of women (Helen in the Iliad and Penelope in the Odyssey). Agamemnon’s dispute with Achilles is also over a captive woman.

Ultimately, in both cultures, the conflicts are worldly. While Greek culture sets its tragic narratives within the framework of human struggle against fate and natural conditions, Iranian culture focuses its epic narratives on the application of human choice and agency.

Let’s consider another comparison. As will be discussed in future lectures, there was a long-standing and deep connection between Iranian culture and ancient culture, with many exchanges taking place. However, there are also differences that distinguish the two. For instance, there are many similarities between the stories of Joseph falling into the well and Bijan falling into the well, yet the subtle differences between these stories reveal the divergence of two distinct frameworks of understanding.

Joseph is cast into the well by his brothers out of jealousy. In the well, he relies solely on God’s mercy, and his emergence from this darkness is interpreted as an act of divine will. Joseph hears the response to his prayer through the voices of the passing caravan. The merchants who pull Joseph out of the well are unaware of their crucial role, mistakenly believing they have found him by chance, and they sell him into slavery for a modest price, allowing the rest of the story to unfold according to God’s preordained plan.

The story of Rostam’s journey through the Seven Labors is an ancient example of the divine narratives within this culture, presented in a highly condensed form.

A comparison between the White Demon’s Cave in the seventh labor and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the earliest philosophical allegory in the world, reveals significant insights.

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, light shines from outside into the darkness of the cave, and the people facing the darkness only see the shadows of the true world outside the cave. In this allegory, the truth (the “Ideals”) exists outside the cave, while humans have their backs to this light and only observe its reflections (the “Shadows”) on the cave wall.

In the seventh labor, Rostam encounters the White Demon in the depths of the cave’s darkness. He defeats the demon and places its liver and brain before King Kai Kaous, which restores the king’s lost sight.

The White Demon’s Cave represents a fissure in darkness, and Rostam’s progress through this deep darkness symbolizes the rooting of the tree of life in the depths of obscurity, nourished by the waters of life (as depicted in the Bundahishn).

The journey through these stages is made possible by “Khwarneh” or “Farah,” which can be interpreted as “divine glory” or “the light of wisdom,” illuminating the path. With this power, the hero ultimately finds light within the depths of darkness and pierces through the heart of truth in the abyss of obscurity.

Bijan, accompanied by Gorgin, sets out to fight the monster wolves but is eventually led astray by Gorgin’s envy and ends up being thrown into a pit. Bijan’s survival in the darkness of the pit is explained through the cleverness and love of his beloved, Manijeh, and he is ultimately rescued by the hero Rostam. The sign of Bijan’s liberation is the sight of Rostam’s ring, sent to him from the depths of the pit as a means of enlightenment. Rostam, the savior, journeys to Turan disguised as a merchant, driven by his will and purpose to solve this problem.

In Persian culture, the theme of travel serves as a symbolic representation of the spiritual journey of the hero through the divine realm and the stages of enlightenment. Significant meanings are embedded in stories with such themes, offering insights into the intricate layers of this world. It is worth revisiting these narratives, including the passage through the “Seven Labors,” which the wise Firdausi invites us to contemplate for the hidden significance beyond their apparent forms.

In the Seven Labors of Rostam, the hero embarks on a quest to rescue a noble king who is imprisoned. Rostam’s father, Zal, advises him to choose the path of moderation. Throughout this journey, Rostam faces challenges against the world, time, and his own inner desires, overcoming each stage with strength and wisdom. During his journey, Rostam experiences detachment and self-transformation, which are key themes in the Seven Labors. Ultimately, in the seventh labor, Rostam encounters the White Demon deep within a dark cave. He slays the demon and places its liver and brain on the eyes of King Kai Khosrow, restoring his sight. The White Demon’s cave represents a dark chasm, and Rostam’s advance into this darkness symbolizes the roots of the life tree being nourished by the depths of darkness (as described in the “Bundahishn”). The journey through these stages is facilitated by “Khorneh” or “the light of wisdom,” which illuminates the path, and it is through this power that the hero ultimately finds light in the depths of darkness 4 and unveils the essence of truth within the profound obscurity.

In the mid-20th century, significant discoveries were made in the deserts surrounding the Dead Sea. In the scattered caves of this region, a multitude of scrolls from the Old Testament and writings from various sects were found, known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Most of these works date from the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE. What initially captured the attention of researchers was the frequent use of martial terminology to describe the battle between the forces of light and darkness, which permeated these ancient texts and indicated the influence of Iranian cosmology on the Gnostic traditions of the Old Testament.

“We know that Bultmann believed that the concept of history or the idea of ‘sacred history’ originated with the Mandaeans, and since Mandaean teachings are significantly influenced by and derived from Iranian thought, the origin of the concept of sacred history should be sought in Iranian teachings. Despite the biased critiques from some scholars in the fields of theology, philosophy, and sociology, especially the partial critiques from Pannenberg and Karl Löwith, the discovery and translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls have presented a completely different picture from earlier Jewish-Christian ideas and have shown the undeniable influence of Iranian teachings on concepts of time, the dual creation of cosmic and material realms, and ultimately on the development of the understanding of history and sacred history.

Such an understanding of sacred history, which, according to Rudolf Otto, is based on the definition and explanation of the idea of divine sovereignty and the ultimate victory of God, as well as the creation of good by God in Iranian teachings, has led to the development of the concept of earthly sovereignty and ultimately to the idea of government. This notion has been explored not only by Rudolf Otto but also by Erwin Rohde, Wilhelm Bousset, Wrightsman, and Joseph von Gall, as well as by Old Testament theologians Peter Frei and Klaus Koch in later years.”

— From the translator’s introduction to the book Cultural Encounters of Iranians and Semites in the Parthian Era

The Journey of the Soul and the Formation of the Concept of History: The Pearl Song

In tracing the essence of the journey of perfection, paying attention to symbols and signs in the stories, alongside examining archaeological data, reveals the gradual formation and intertwining of ideas and concepts.

One notable example in this context is the Pearl Hymn; 5 the oldest surviving written versions of this ancient hymn are in Syriac and pertain to regions within the cultural domain of the Parthians. The hymn is included in part of the Acts of Thomas and was well-known among Christians.

It also appears to have been among the songs of the bards used to propagate Manichean teachings. By examining the content and symbols of the work, such as the symbolic connection between the celestial seed and the earthly womb, the rebirth of the deity Mithras, and the mother figures associated with water and earth (Anahita and Spandaramati), as well as relating this story to certain archaeological findings, the ancient origins of some of its concepts in Iranian culture become evident.

A shift in awareness has occurred here, which is the very change that leads Hegel to describe Iran as the first historical land. The concept of “history,” in the new era’s awareness, began with intellectual debate between the ancients and moderns in Europe and flourished in the Germanic world.

In the context of the break from “sacred history,” where German idealism provided a foundation for new sciences, there was a particular focus on finding the origins of the concept of history based on the ideas of Rudolf Bultmann. This quest can be considered one of the greatest projects of the modern era. Bultmann traces the formation of the concept of history through the development of “sacred history.” He argues that the roots of the concept of sacred history in Christian thought should be sought in ideas from the Mandaean religion, as from this perspective, “baptism” is the initial moment of linear history, and Christianity inherits the older Mandaean tradition in its rituals related to baptism and its narratives of John the Baptist.

Moreover, there has been a broad connection between the sources of Manichaeism and Mandaeanism. The Pearl Hymn, appearing in both the Acts of Thomas and Manichean texts, serves as evidence of this connection.

The Pearl Hymn is a Gnostic text with a Parthian cultural origin. The oldest written version of it, in Syriac, is recorded in the Acts of Thomas, and it appears to have also been popular among Manichaean gossans, according to available evidence.

The Pearl Hymn presents an allegorical narrative of a journey. A young prince, the son of the king and queen of the East, is tasked with retrieving a pearl guarded by a serpent in the sea of Egypt. Along the way, the young prince becomes so engrossed in the events and adventures of the journey that he forgets his mission. It is only when his father sends an envoy in the shape of an eagle to remind him that he recalls his quest. Ultimately, the prince defeats the dragon, acquires the pearl, and returns to the East, donning his royal robes once again.

The core of the story is based on the distinction between two realms: light and darkness. The prince’s journey begins in the realm of light and, after traversing through darkness, culminates in a return to light. The realm of light, as later seen among some Iranian philosophers, is simply referred to as the “East.” Shahrastani, in his Illuminationist Philosophy, not only utilizes the metaphor of the “East” but also retells the ancient structure of the story, portraying a wandering traveler who, having forgotten his true home, returns to the East and light by finding the “pearl,” which in his narrative is hidden in Mount Qaf.

In ancient Iranian beliefs, a pearl was thought to form from a raindrop that lodged inside a shell; in other words, the shell could become impregnated with a divine celestial essence. Thus, the pearl, this gem born from flesh, symbolized divine grace.

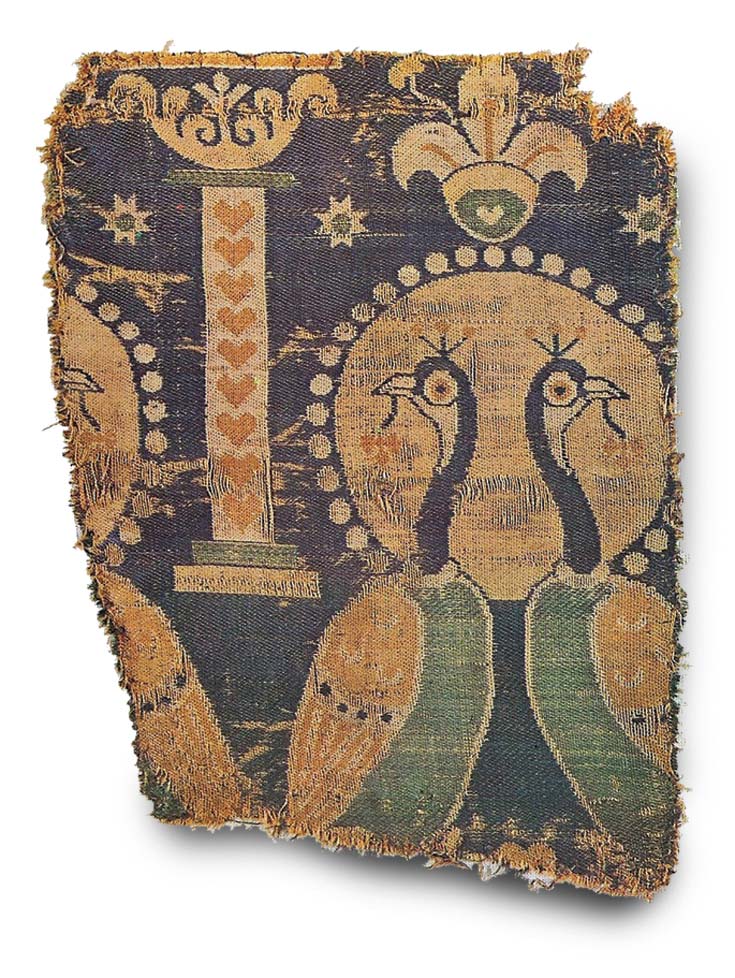

One of the most prominent recurring motifs in Parthian art, especially in the luxurious textiles that continued to be produced for centuries after the fall of the Sassanian Empire, is the image of a peacock or other bird holding a pearl in its beak. Typically, this entire image is framed as a symbol of divine grace within a halo of pearls.

This Parthian motif depicts the lifting of pearls from the depths of the sea by the colorful peacock, which represents the heavenly Simurgh on earth, and its gift to humanity. How can we understand the significance of such a motif without awareness of its multiple historical references within this culture?

Several of the most distinguished and oldest surviving textile fragments from the Sassanian period are preserved in European churches. These pieces form an important part of the tradition of collecting Christian relics from Eastern lands, which were gathered in treasuries.

All these textiles are adorned with motifs that, rooted in the Parthian tradition, symbolized the glorious Soshyant.

Now let’s view the Pearl Song from this perspective: it is an allegorical narrative of a journey. A young man, the son of the king and queen of the East, is tasked with retrieving a pearl guarded by a serpent in the Egyptian sea. The young man becomes so engrossed in the events of his journey that he forgets his mission. Eventually, the king sends a messenger to remind him. In the end, he successfully completes his quest and returns to the king with the pearl, becoming one of the princes—or, in the Persian terms used in the Syriac text of the song, “waspuhran.”

The foundation of the story is based on the distinction between two realms: light and darkness. The prince’s journey begins in the realm of light and, after traversing through darkness, concludes with a return to light. The realm of light is here simply referred to as the “East,” a term also used by later Iranian philosophers. Some key elements of this story can be found in the philosophy of illumination (hikmat al-ishraq) by Suhrawardi; for instance, the use of the metaphor of the “East” and, more broadly, the theme of a wandering traveler who forgets his original destination and ultimately returns to the East and light upon finding the “pearl,” which in Suhrawardi’s narrative is hidden in the Mount Qaf. The metaphor of the “Egyptian” land, associated with sorrow, also persists in Suhrawardi’s story. 6

Widengren also refers to the Parthian origins of the Pearl Song. He is among those who view the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls as evidence supporting the influence of Iranian ideas on the formation of concepts such as time, creation, the universe, the divine realm, the material world, and the afterlife in Jewish-Christian thought.

Rudolf Otto considers the idea of divine kingship, the creation of goodness, and the ultimate victory—rooted in Iranian cosmology—as fundamental in shaping the concept of worldly kingship and the resultant notion of “state.” In Iranian kingship rituals, the sovereignty begins with a covenant, 7 symbolized by a covenant ring. One of the oldest surviving examples of such symbolic rings is a golden ring discovered in the Arjan (Behbahan) excavations. This ring terminates in two shell-like plates; the grooves on these plates evoke the image of the lotus flower, whose seed is a pearl and which is also associated with the shell in the depths of sacred waters.

In ancient Iranian beliefs, pearls were thought to result from the womb of a shell being impregnated by rain; through the gift of rain, the shell becomes imbued with divine grace from a celestial seed. In this way, the pearl, a gem born from flesh, symbolized divine grace and the savior figure, the Soshyant, who brings liberation to humanity. 8

In Christianity, the symbolism of the shell and the pearl was used, among other things, to depict the relationship between Mary and her child. Additionally, John the Baptist, who heralded the coming of the Savior/Messiah, was often depicted holding a shell. Consequently, in churches, baptismal fonts or other tools used in the sacrament are still crafted in the shape of a shell.

Rumi builds upon the initial idea of the womb that receives life, creating a new composition with the concept of “the heart of Mary,” adding a subtle layer of meaning to this ancient symbol.

“Mary of the heart cannot bear the light of Christ / Until the trust reaches from the hidden to the hidden. When the sense is awakened, it never dreams / Until the heart departs from this world, it will not reach another world.”

In the Gathas, there is a narrative about the birth of Zoroaster that bears a strong resemblance to the story of the divine glory traveling with rain from the heavens to the womb of the pearl. In this narrative, the heavenly parts of Zoroaster descended from the sky in the form of raindrops, and the womb of his mother, Dugduya, received this rain. In some Latin accounts, John the Baptist, who foretells Christ, is also depicted with a shell in hand.

One of the oldest examples of the motif of pearls and shells, which clearly embodies the idea of divinity, might be the shell-like plates found in the Argjan ring.

Many other examples of this motif can be found in the art of later periods. In the exquisite textiles of the Parthian and Sassanian eras, which continued to be produced for centuries after the fall of the Sassanian Empire, one of the most recurring motifs is the peacock or another bird, which is depicted with a halo signifying divine grace and holding a string of pearls in its beak. The depiction of a colorful peacock retrieving pearls from the depths of the sea—symbolizing the celestial Simurgh on earth and granting it to humanity—cannot be fully understood without acknowledging its numerous references across different historical layers.

These fleeting references to pearls or other motifs aim to draw readers’ attention to the mysterious and subtle aspects of Iranian art. In this cultural center, the manifestations of the spirit are highly diverse, and it is challenging to arrive at a clear and comprehensive map. Symbols and concepts have continually evolved and transformed across different domains. The network of connections between a rock carving, a piece of goldwork, and a textile design traverses a labyrinth of time and history, during which awareness has been continuously renewed on its foundational layers.

The fundamental question of “Who should wield the Seal of Solomon?” demands an answer at each new stage of awareness, and reaching that answer is often complex, requiring solid foundations in the prevailing belief system. The development of the idea of “divine grace” for individuals, which differed from the delegation of power to shamans, local kings-priests, or king-gods of the land, could intertwine various scattered concepts around a central narrative. This process led to the formation of a system where cosmic roles had specific earthly counterparts, and the establishment of power entered a new phase.

The signet ring of Nafisi, discovered during the Arjan excavations in the 1980s, dates back to a period before the formation of the Achaemenid Empire. It is an archaeologically significant discovery for tracing the origins of the Persian school of thought. The ring terminates at both ends in two shell-like plates; the grooves on these plates evoke the image of a lotus flower, a bloom whose seed is pearl-like, and which itself is a companion to the shell in the dark depths of the sacred waters.

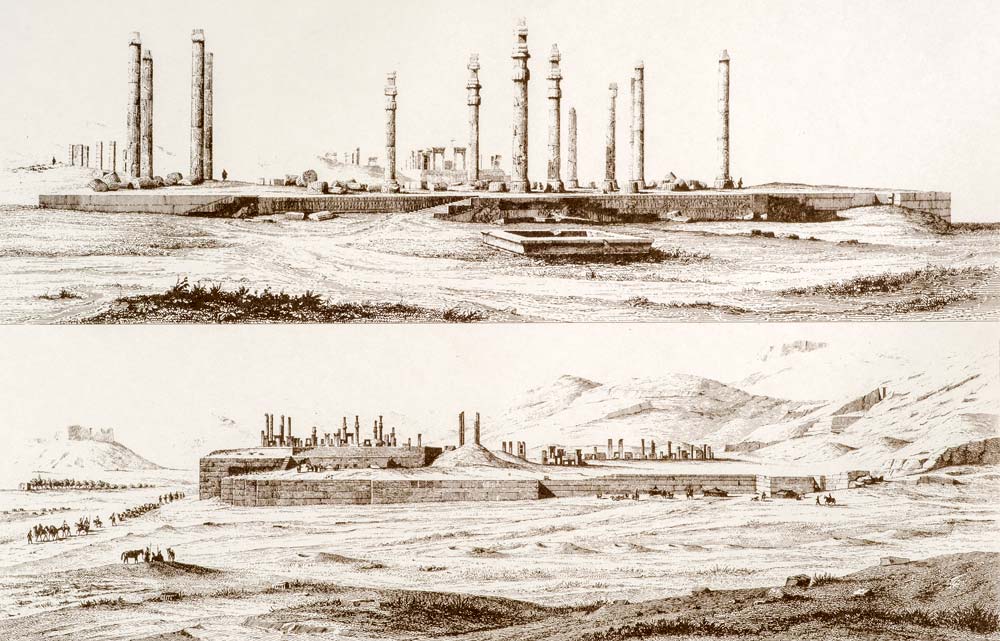

Persepolis and the Epic of the Soul’s Journey

Now, let’s take another look at the architecture of Persepolis, also known as Parseh, but this time through the lens of the soul-hero’s journey in the epic struggle of existence. We will focus on the central idea that channels the forces within this epic—the emergence of a new concept of power, manifested in the figure of the “charismatic sovereign,” which has the potential to establish authority.

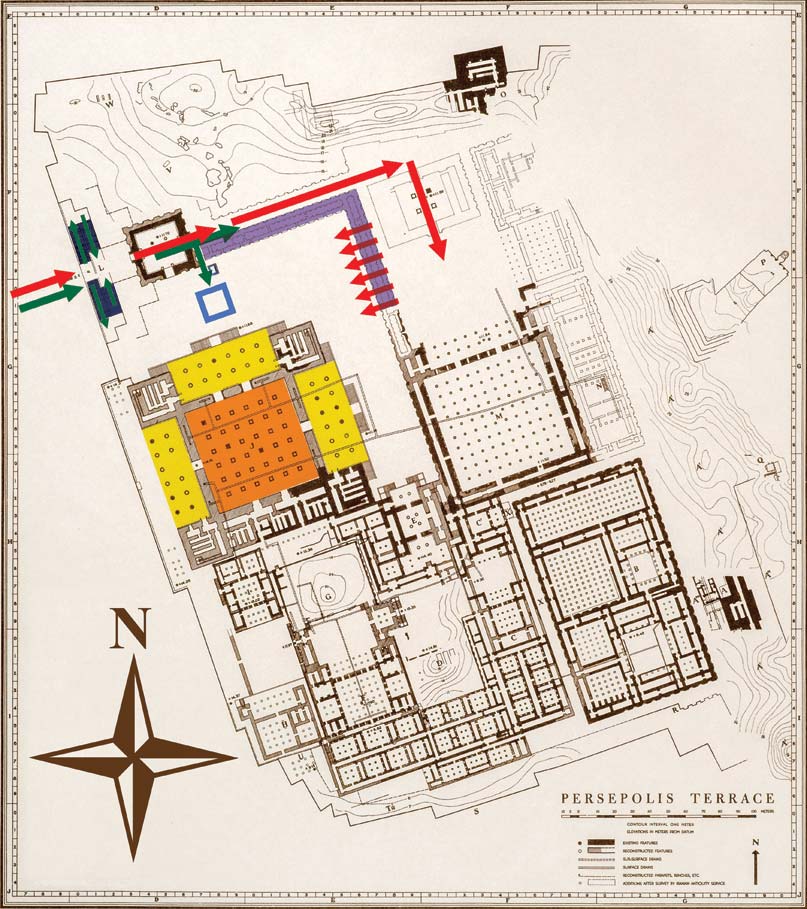

The complex of buildings at Persepolis represents the most perfected historical achievement of the Persian school and reflects a consciousness rooted in the Iranshahr epic. Therefore, it is fitting to recall the points made in previous discussions about the new urban planning system that emerged during this period:

One of the hallmarks of urban planning in the Persian school is the definition of the continuity of urban life based on the relationship between cities. From this perspective, a network of land and water routes, along with engineering structures, was developed that connected and linked these cities. These historical routes went beyond the primitive paths that merely met the basic needs of the inhabitants; they served a larger idea that we now recognize as “strategic geography.” Thus, a transportation, communication, and support network was created, with the potential for global expansion. 9

In the architectural tradition of any culture, the choice of location for constructing significant buildings has been based on the most fundamental ideas of that culture, in a way that was directly meaningful to the people of that time and place. For example, in the construction of sacred structures, depending on the cultural awareness of the society, locations such as the source of an ancient spring, the point where a river’s branches split, the place where winds converge, or a site atop hills overlooking a city—believed by the public to be the setting of mythical events—were often chosen.

The terrace of Persepolis is shielded to the north, east, and southeast by a mountainous barrier, now known as Mount Rahmat. The height of this mountain is not so towering as to divert the observer’s attention from the platform and the completed columns of the structures, unlike Greek and Buddhist temples, which were often built within the majestic isolation of remote mountains. Those approaching the terrace from the only available route, coming from the Marvdasht plain, would not have seen the structure enveloped by the imposing vastness of mountains, whether from a distance or when standing before the gate and entrance stairways.

Additionally, a specific “run” was chosen for the construction of this complex. In Iranian architectural terminology, “run” refers to the orientation and alignment of a structure in relation to the cardinal directions. 10

In general, there are six different “runs” in Iranian architecture, each chosen to achieve the optimal conditions regarding sunlight angle, wind direction, water flow, flood paths, and other natural influences specific to each climate. Within this architectural system, one particular run is typically preferred for constructing sacred sites, and this is the same run that was selected for the Persepolis complex.

The location and design of the angle at which the complex of buildings is situated within the natural landscape suggest that the designers paid special attention to light and the movement of the sun. It is likely that one of the primary ideas of the original designers was focused on the moment when the first rays of the morning sun become visible. This moment appears to hold a fundamental significance in the ancient Iranian philosophy and wisdom of the Khosravi tradition, as the sight of the first rays of morning sunlight is seen “as the vision of the eternal dawn’s fire.” 11

In Khosravi wisdom, the sight of the first light of dawn (referred to as Bahman light or the ray of Vohumana, representing good thought) symbolizes the end of darkness or the end of the ignorance that darkness represents.

A pearl is a rare gem that settles on a ring after a long journey. In this framework, the meaning of gems is a metaphor for a journey towards exaltation. Each gem is a cosmic traveler, emerging from the earth and shining at the end of its journey, either on the band of a ring or atop a crown.

In each period of its flourishing, Iranian culture has nurtured a variety of meaningful and transferable narratives by blending different aspects of life into astonishing, delicate, and multilayered stories. These narratives address both the general public and specific individuals on various levels. This culture has a unique capacity for nurturing core themes; through recitations, poetry, and songs, an idea is developed and disseminated in its various aspects, creating a global impact.

Today, we can trace the evolution of these stories, which have continually evolved alongside growing awareness, through some borrowed meanings found in other cultures. This is because, after several transformations, following the path of changes from their original form can sometimes be challenging. For instance, the Pearl Song, which has persisted in its original form within Christian culture, illustrates this continuity.

Paying attention to this moment of the first dawn is crucial and is reflected in the design of buildings and the selection of the locations for the most important inscriptions. The progression of light from dawn to its transformation into a “radiant disc” in the dark western horizon was understood as a “divine manifestation” symbolizing the cycle of the awareness of life.

In subsequent centuries, the distinction between two types of radiance—one as light in its manifest state, and the other as light engulfed in darkness, which Suhrawardi referred to as qasaq—and the emphasis on the awareness of the traveler or seeker to discern the meaning of these two lights continued to develop. This wisdom was further elaborated in the thought of Suhrawardi, the Ishraqi philosopher, who, in his specific terminology such as “the light of the lordly ones” and “the light of Bahman,” referred to much older sources of this thought. Suhrawardi proposed a hierarchical approach to infusing the lordly lights into darkness. As he stated, “The dawn of awareness rises in the sunset of thought or the western world,” and he termed this as the “Red Intellect,” a concept equivalent to the “Red Ruby” found in the Shahnameh.

From this perspective, the choice of the run for the construction of the sacred site at Persepolis holds meaningful connections with the ancient Khosravi wisdom of the Iranians. The placement of the complex relative to the mountains is such that the sun does not emerge from distant natural horizons here; rather, each season, the celestial boundary of this site aligns with the “moment of the morning twilight.” The western view of the building also faces the vast expanse of the plain to the west of the terrace.

In this wisdom, the light that first touches the entirety of the structure and gradually illuminates it until sunset represents a movement from the twilight of awareness to the boundary between “illuminated enlightenment” and the “darkness of ignorance.” It should be noted that, as Corbin points out, “the reception from the East, in the view of Suhrawardi and the Ishraqis, does not correspond to the geographical East that can be found on a map but rather signifies a metaphysical realm.

This term denotes a spiritual world and the “Supreme East,” 12 from which the intellectual sun rises. The “Easterners” are those whose inner abode embraces the fire of this eternal dawn.” 13

Persepolis is not a military fortress. It is not a royal residence. Nor is it a temple for the gods. Instead, it is a gateway to a new awareness that has emerged from the diverse capacities present within it. Here, through the intersection of various aspects of social life, a complex has been established where the multiplicities find unity in a meaningful reflection.

Corbin explains the meaning of “khwarneh” (Avestan) or “khoreh” (Persian) as follows: “It is a light that emanates from the divine essence, through which certain forms gain superiority over others, and every individual becomes capable of certain activities or crafts.” The term “khoreh” denotes the dwelling of the light of majesty in the souls of the benevolent kings of ancient Iran, with the best examples being the kings Bahram, Fereydun, and Kay Khosrow, whose souls themselves are like fire temples.

The Shaykh al-Ishraq revitalizes the ancient Khosravi wisdom with the awareness of his own time. He reuses terms like “khwarneh,” referring to it as a special angel of humanity, which manifests in the Jam-e Jam. Suhrawardi’s references to the functions of the Amesha Spentas (Holy Immortals) as “forces” reflect the flourishing of this intellectual heritage in his thought. Suhrawardi provides a symbolic depiction of the angel he regards as the “lord of the human type,” 14 describing it as a being with two wings, one of light and the other of darkness.

In the treatise The Song of Gabriel, the angel, referred to as the “Red Intellect,” explains to the one who sees him in a dream the color in which he has appeared. This red is the twilight hue, a blend of night and day, light and darkness. 15

From the site placement and design of the angles of the buildings within the natural landscape, it appears that the designers of Persepolis paid special attention to light and the movement of the sun. It is likely that one of the initial ideas of the designers was focused on the quality of the moment when the first rays of the morning sun became visible. This moment seems to have held fundamental significance in the Khosravi wisdom of ancient Iranians, where the sight of the first rays of morning sunlight is considered “like the vision of the eternal dawn’s fire.”

Experiencing this moment is an inward phenomenon for each individual, representing a connection to the realm of Bahman (Vohumana), the embodiment of good thought (the First Intellect), or, in other words, a summons to it. In this thought system, “Dena” or “religion” has acquired an inner dimension—where “Dena” signifies inner vision, in contrast to “Din,” which is an external matter concerned with the implementation of religious law (similar to the concept of Rajas in Hindu thought).

Additionally, in this epic framework, one of the material forms of khwarneh is stone; 16 Stone is an ancient substance that carries an eternal memory, with light concealed within it and time trapped inside. Stone is associated with the concept of khwarneh in the sense of both beginning and end, origin and destination.

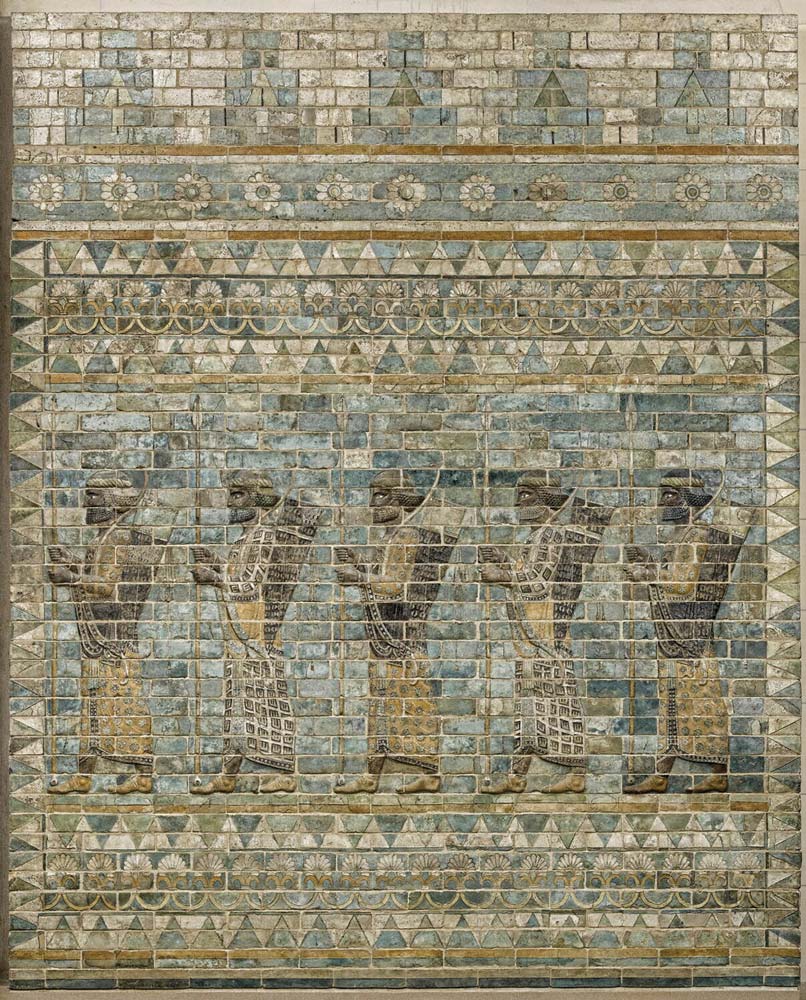

To gain a better understanding of the remains of stone buildings from this period, it is important to note that these structures were originally adorned with colors, from the walls and columns to the reliefs. In addition to the glazed bricks with vibrant colors discovered at the Apadana Palace in Susa, particles of pigments and fragments of silver and gold leaf have been found on parts of the reliefs and columns at Persepolis, which help to visualize the original appearance of the buildings. The colorful reliefs, both in interior spaces and exterior facades, indicate that the spirit of these structures was entirely different from the current state of the ruins. This is particularly interesting for tracing the continuity and evolution of Iranian art, as it provides a clue to the tradition of incorporating color in Iranian architecture, a practice that, despite numerous changes, has persisted into later periods.

In every artistic tradition, the structure of the works themselves is key to understanding the core idea. In the fundamentals of Iranian art, color is not merely an ornament (as it might be in Western art under tonal structures) but rather a structural essence.

The rank of piety

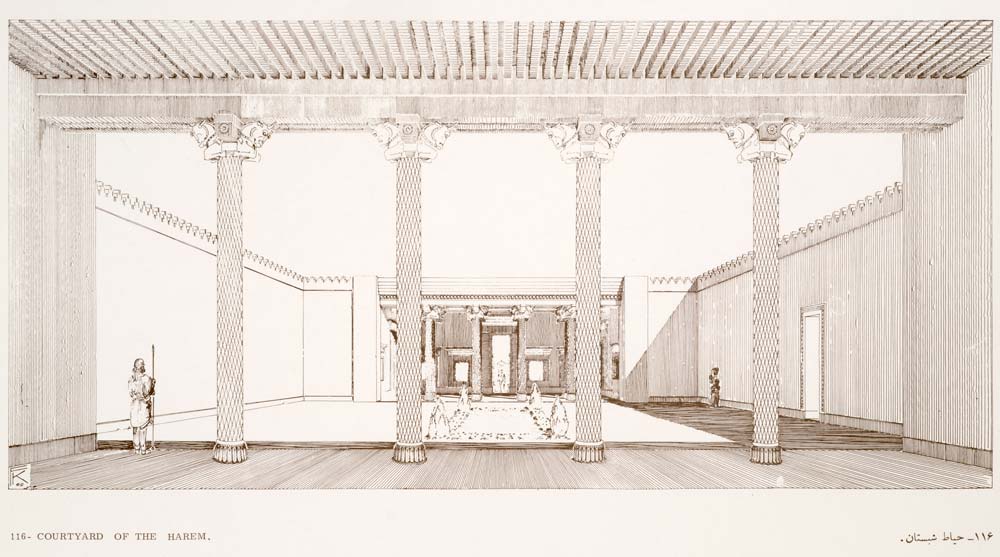

The Persepolis complex is not a palace in the conventional sense used for royal residences. Recent research has undermined the validity of this common theory. Even archaeologists who were not fully acquainted with the latest findings of their time, such as Krefter, Roman Ghirshman, and Louis Vandenberg, have pointed out the different usage of this complex. Ghirshman notes that the layout and use of the spaces within this complex do not suggest a military function, and in terms of protection, it is completely defenseless.

In contrast to most palaces, which are situated in strategic and inaccessible locations and often conceal their entrances, the entrance staircase of Persepolis is open with numerous short steps.

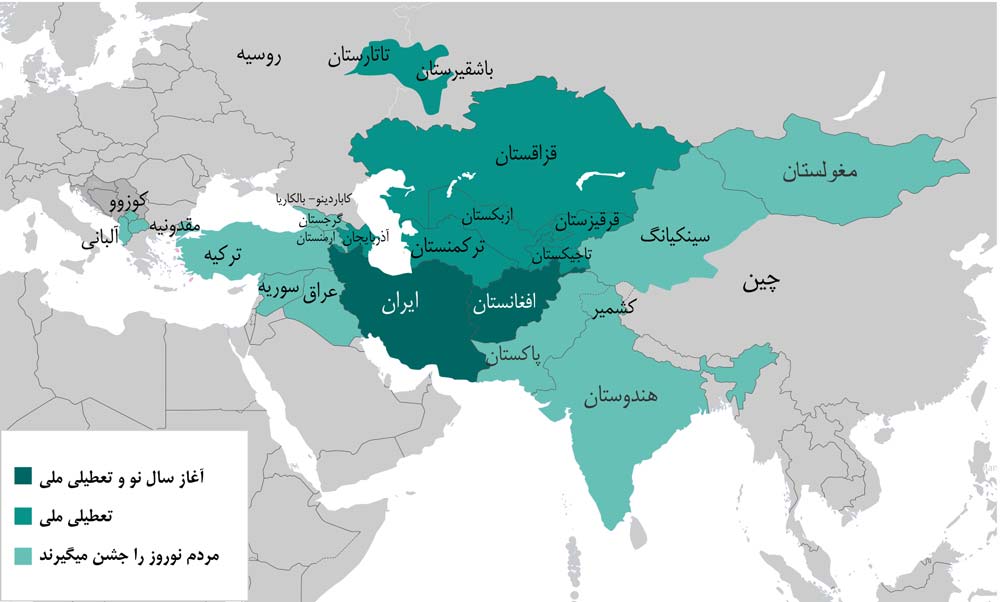

Evidence suggests that the Persepolis complex served as a venue for large gatherings, such as celebrations under what we term “Pious Rituals,” which likely included significant festivals like Nowruz, Tirgan, Mehrgan, and Sadeh.

One of the most significant achievements of holding these festivals at their designated times and repeatedly was the ability to synchronize distant communities. This marked the beginning of a major intellectual transformation in ancient times. Prior to this, there was no tradition of conducting such comprehensive and ethnically inclusive rituals among communities with such diversity and across such vast geographical expanses. Therefore, it is not an exaggeration to call Persepolis the first “city-capital” of thought and culture.

Ritual sites in the ancient world are abundant and found everywhere; however, what distinguishes this culture is its view of the “Other,” which, in other civilizations, was often separated from the “Self” based on narrow local, ethnic, or blood ties.

In many cultures, such as Greece, the demarcation with foreigners, who were labeled as “barbarians,” was a fundamental principle supporting the power of local culture. The Acropolis or the temples of Crete were sacred places of worship for the local inhabitants, and their doors were kept closed to outsiders. The doors of Hindu ashrams or ancient Egyptian temples were never open to foreigners. The Jewish temples in Jerusalem were even closed to non-priests.

In this context, the annual repetition of rituals at Persepolis for several centuries laid the groundwork for the development and promotion of shared rituals and the expansion of ceremonial themes, which have continued in a highly diverse form to this day. Along with this, a system of ideas, motifs, symbols, and signs spread to distant regions. Consequently, to this day, peoples who have a historical connection to the celebration of these rituals continue to exist within shared cultural circles. Common roots of rituals, festivals, symbols, and temporal understandings can be identified among them. In contrast, groups outside this realm or unaware of it are distinct with different cultural symbols. The shared ritual symbols across this vast geographical area cannot be explained solely by racial or even linguistic commonalities but must be traced to the influence of related beliefs and the ongoing practice of shared rites.

The annual repetition of rituals for several centuries provided the foundation for the development and promotion of shared ceremonies and the expansion of ceremonial themes, which have continued in a highly diverse form to this day. Along with this, a collection of ideas and cultural elements spread to distant regions. As a result, to this day, peoples who have a historical connection to these rituals remain within shared cultural circles, and common roots of rituals, festivals, symbols, and temporal understandings can be identified among them. In contrast, groups outside this realm or unaware of it are distinct with different cultural symbols. The shared ritual symbols across this vast geographical area cannot be explained solely by racial or even linguistic commonalities but must be traced to the influence of related beliefs and the ongoing practice of shared rites.

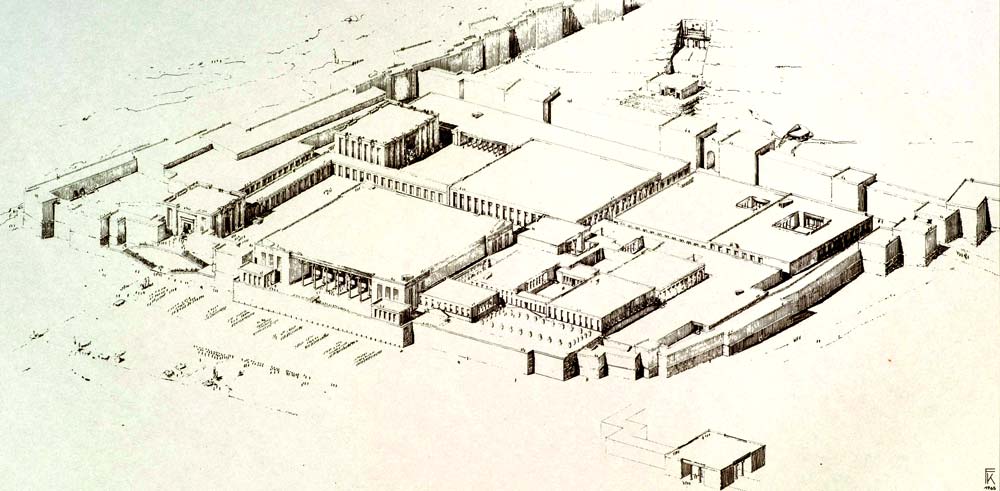

Now, alongside a traveler who has embarked on a journey to participate in one of the ritual festivals, we head towards Persepolis. After what may have been an exceptionally long journey, the traveler progresses along a road leading from the west towards the east to enter the monumental complex on the terrace. The entrance gate faces west, symbolizing the idealized realm of the eastern (Persian) light.

As the traveler follows a winding path starting from the entrance steps in the northwest, they approach the first gate, commonly referred to by Orientalists as the Gate of Nations. They proceed through a corridor and, after entering the second gate (known by Orientalists as the Gate of Xerxes), they turn right into another corridor and then turn right again to reach a central garden area within the complex.

In the center of this garden space, there is a rectangular pool and a pavilion. 17

From the continuity of rituals, it can be inferred that the contents of the pavilions were likely a drink used for the beginning and end of Persian ceremonies. These general characteristics are also observed in most four-iwan mosques, which are the epitome of ritualistic architecture in Iranian design.

These characteristics include: a spiral-shaped entrance that guides the traveler through a winding path towards a central courtyard; at the entrance of this central courtyard, there is a pavilion, and in its center, a water basin. Compared to those in Persepolis, the pavilions in later works are more refined and smaller. These pavilions are a significant element also found in structures influenced by the Persian architectural style in the eastern Mediterranean, including the buildings of the Commagene and Palmyra during the reign of Antiochus.

In this context, the water basin introduces one of the four elements: water. Water represents the earthly form of the divine spirit Khordad (or Haorvatat, meaning perfection), and it plays a role in symmetry, becoming one of the principles of Iranian architecture. It mirrors the sky, or Asha-Vahishta (meaning cosmic order), reflecting the grandeur of the cosmos and the earth (Armaiti). Additionally, water reflects the celestial brilliance, which is Vohuman (or Vohu Manah, meaning good thinking), a manifestation of the element of fire. Finally, water embodies the angel Ardvira (or Anahita).

The main entrance to the Persepolis complex is located on the western side of the platform. One must ascend the gently sloping and inviting steps of the Apadana, pass through the gate, known as the “Gate of Nations” by scholars, and then turn right to enter a central courtyard.

This design approach, which is later repeated in Iranian architectural schools, particularly in the construction of ceremonial buildings, ensures that the visitor does not immediately enter upon passing through the gateway. Instead, the visitor is guided through a winding path, which branches off at least once, leading to a central courtyard, typically featuring a water basin at its center. Additionally, many other core elements of Iranian architecture, which evolved significantly in later periods, are visible in the Persian architectural style, including the design of porticos, iwans, and colonnades surrounding the courtyard.

In this map, the green path indicates the original entrance route to the Apadana festival area at the beginning of Persepolis’s construction. The red path represents changes in the entrance design after the construction of the porticos. It appears that the entrance gate of the second path was part of the ongoing construction, which remained incomplete at the time of its destruction. If the planned extension of the palace to the north, of which there are some remnants, had been completed, the Apadana stairs (marked in navy blue) would likely have been placed at the center of the symmetrical complex.

Additionally, in this design, the locations of the large platform, of which remnants still remain, and the pool seen in one of the 19th-century designs are marked with blue squares. The iwans of the Apadana Palace are highlighted in yellow, its hall in orange, and its colonnades in purple.

The role of the water feature was later solidified in Iranian architecture. It became representative of everything that can be understood through the notion of human perfection in Iranian thought and culture. In this perspective, a person is seen as body, soul, spirit, intellect, and divine grace. Ascending towards perfection is understood through the concept of devotion and moderation.

The water feature serves as a place for the “padyāba,” 18 or the cleansing of the body and soul, and a renewal of the covenant with one’s conscience and vital force. Ultimately, the water feature is a reflection of human presence in existence and a point of connection in the world where one can see their own face mirrored.

Here, abstract concepts find a tangible form through culture and art; for instance, if the general idea of this intellectual tradition—that “existence is the manifestation of Ahura Mazda, and humans are his manifested allies”—brings forth an abstract concept of “manifestation,” art makes it measurable and tangible.

Countless techniques of symmetry, repetition, and the use of reflection and mirroring are products of a mindset that views the world through the concept of manifestation.

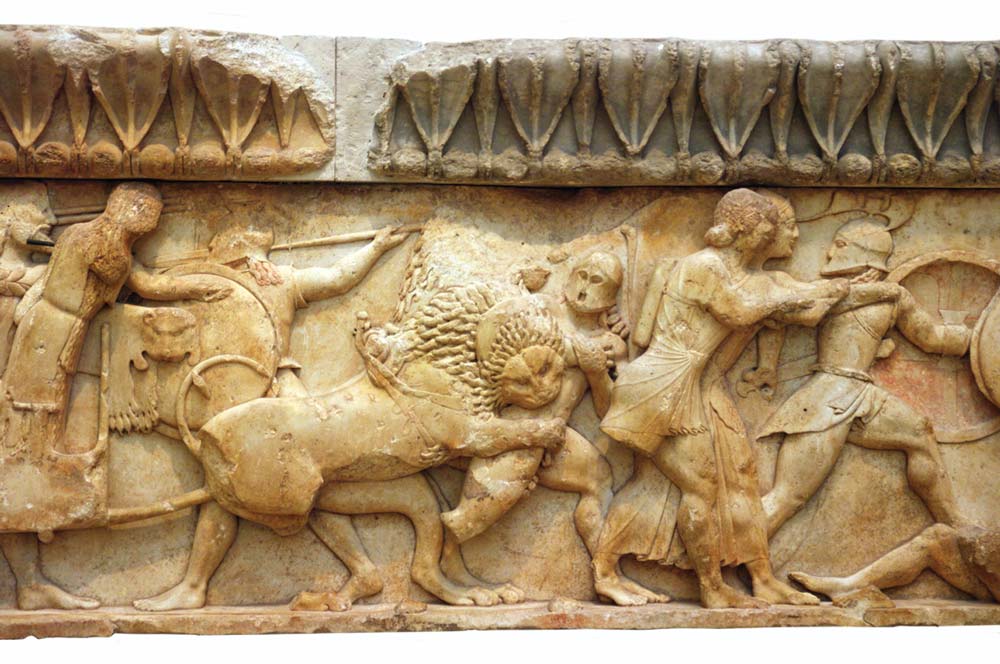

The interpretations of many Orientalists and European historians regarding the motifs at Persepolis reveal their unfamiliarity with the fundamental themes and symbols of Iranian culture. For example, Ghirshman interprets the lion and bull motifs on the Apadana staircase as representing the “victory of the forces of good over the forces of evil.” However, there is no evidence to support the idea that the bull was considered evil in this culture; on the contrary, in the Gathas, the bull, or Gaoš Urvan, is the first victim of the demon’s assault on the world.

Similarly, Ghirshman’s interpretation of the depiction of a man holding a lamb on the stairs of the Tchogar palace as representing “bringing lambs for roasting and feasting” is misguided. The sources of the theatrical narrative that some Orientalists have envisioned for this site resemble more the tales of medieval European kings, with little evidence supporting such a view within the site itself.

It is clear that in both the overall architectural design and the details of the motifs, there is no sign of personal tastes, nor is there evidence of differentiation between rulers or periods, or of the expression of power stemming from a new will. Typically, in the design of palaces and the residences of rulers, the personal taste of the ruler or those who benefit from the site is involved. However, the design of this complex progresses in a consistent manner.

The construction project of Persepolis began under Darius the Great and continued for several centuries until the attack by Alexander the Great, during the reign of Darius III. The project was ultimately never completed. The single capital of the Simurgh on the northern side of the site and several other half-finished capitals indicate that the design of the complex was still expanding.

The term “Run” in Iranian urban planning refers to the orientation and angle of buildings relative to geographical directions. Generally, there are six Runs in Iranian architecture, each chosen to optimize factors such as sunlight exposure, wind direction, water flow, and other natural influences based on different climates. For instance, the Run for Kerman is oriented towards the east.

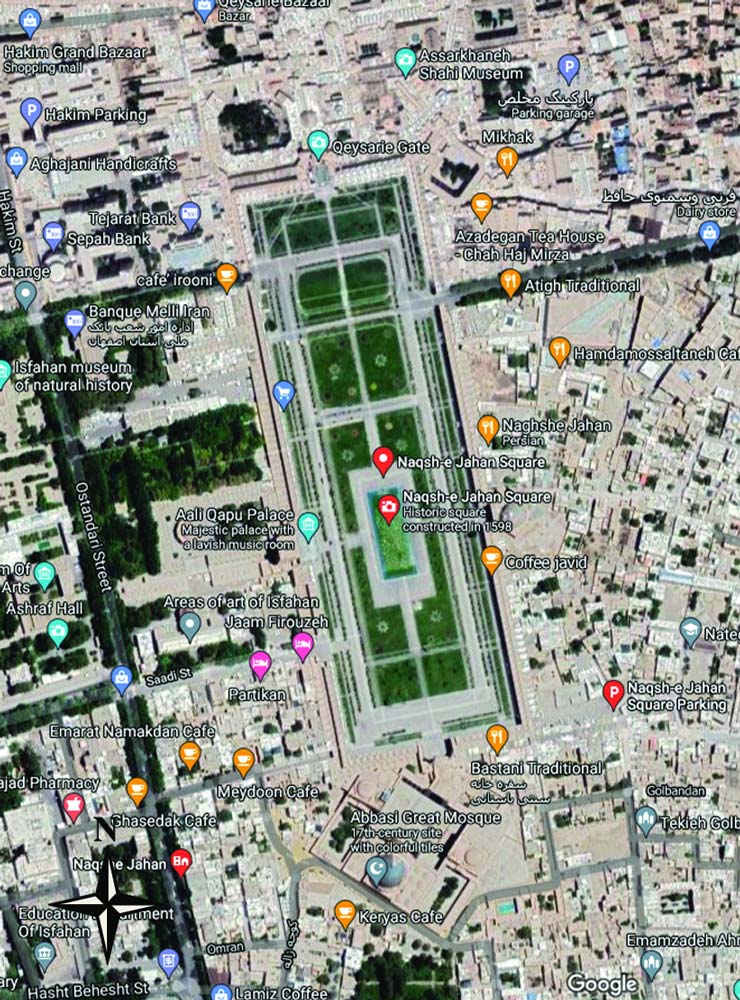

In this architectural system, some uses favored a particular Run. For example, in Islamic architecture, special attention was given to the direction of the qibla. Notably, the Run for Persepolis was repeated in ritualistic structures where the establishment aspect was significant. Even two millennia later, the same Run was chosen for the design of the Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan. This is particularly meaningful given that the design of this square and its associated buildings was approved by the founders of the Shah Abbas era to mark the beginning of the 1000th year of the Hijri calendar.

According to Iranian historical tradition, the “Millennium Head” was regarded as a decisive demarcation, marking the beginning of a new cycle in history and the arrival of a savior. Thus, the design of this square would have been based on the most solid foundations of this culture.

The continuity and consistency of work over such an extended period suggest that the design features of the space are the result of a well-developed thought process, serving a coherent and enduring idea. This idea was intended to reach a broad audience, spanning both contemporaries and future generations.

As previously mentioned, no historical motif appears in a fully developed form spontaneously; rather, the seeds of awareness grow and mature over time. The Persian School itself is a testament to how, from familiar meanings, a new awareness emerges. Most of the motifs used were already established in the visual memory of people coming from the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, the Nile, the Indus, and the Oxus regions. These familiar motifs, under the new framework of awareness, invite observers to a different horizon.

In essence, here we see a collection of very ancient concepts from the experiences of the people of this land, combined with other intellectual influences that were not necessarily rejected due to their foreign nature. This amalgamation created a unique spirit with its own specific order and norms. The most apparent manifestations of this spirit are found in culture and art.

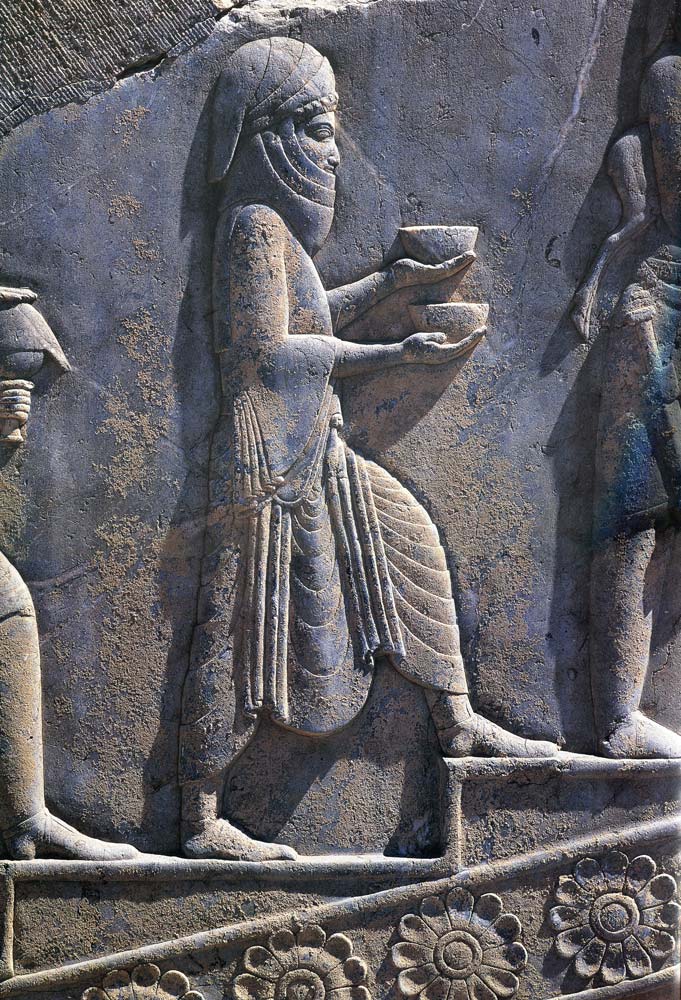

Researchers have noted that although there are similarities with Mesopotamian motifs here, the differences also attract attention. In the series of scenes depicted in Persepolis, there are no representations of war, military campaigns, or bloodshed, which are typically detailed in the bas-reliefs of Assyrians showing conquests and the subjugation of enemies. Additionally, the use of traditional visual motifs in this school serves new meanings.

In the collection of motifs, the image of the cypress tree is frequently repeated. Among the groups and assemblies of people, the cypress tree is prominently depicted. The cypress symbolizes the immortality of life itself and represents the divine spirit Amordad (Amesha Spenta = Immortality). The cypress trees are consistently shown with an emphasis on their strong seeds, reflecting the concept of the “primordial tree” (as described in the Bundahishn). This resilient, ever-green, and fruitful tree signifies fertility, dispersion, and the expansion of the world, representing the hope for the continuity of the life force of the idea around which people have gathered.

In the journey of Iranian architecture from the Persian school to subsequent schools, the use of color and attention to the angles of light have been fundamental elements. The colorful surfaces of buildings reflect their joyful essence. This approach finds its roots in the epic foundation of this culture, which values the triumph of life, prosperity, and culture over destruction, drought, and death. Every beautiful building signifies this victory. The highest expressions of these colorful surfaces creatively use glazing techniques to reflect certain lights in the form of arcs and rainbows.

On the other hand, various techniques, based on sensitivity to the angle and intensity of light, gradually contributed to “coupled” themes. For instance, light in different angles seems to alter certain forms; for example, the designs of niches and muqarnas (ornamental vaults) appear to open and close like a flower under different lighting conditions.

Thus, a building continuously presents itself anew to the observer in light and shadow, embodying the Phoenix or the idea of perpetual creation in Iranian thought. The application of these techniques in the design of mosques, schools, and houses transforms the solid structure into poetry. The role of color in this architecture cannot be explained merely as decoration; rather, the patterns and colors represent the delicate essence or spirit of the work.

Looking at the most refined achievements of this long journey makes it easier to understand the initial steps that carried the seeds of future possibilities.

The lotus flowers, particularly the water lily and the iris, are frequently depicted. The lotus symbolizes fertility and the abundance of life (Haurvatat). This flower, whose seeds are akin to pearls nestled in the depths of a shell, rises from the dark swamp towards the light of the sky. In Iranian art and cultures influenced by it, the lotus is a symbol of “life” and is associated with Anahita.

The iris, growing in mountainous heights, symbolizes sovereignty and righteousness (Shahrivar/Kshathra Vairya). Additionally, the palm leaves depicted at the base of columns, either moving downward or spiraling around the column shaft, represent return and are symbols of conscience and divine glory. Alongside these four plants, four animals are also frequently depicted: lion, bull, eagle, and scorpion, either in full or as parts of their bodies in composite creatures.

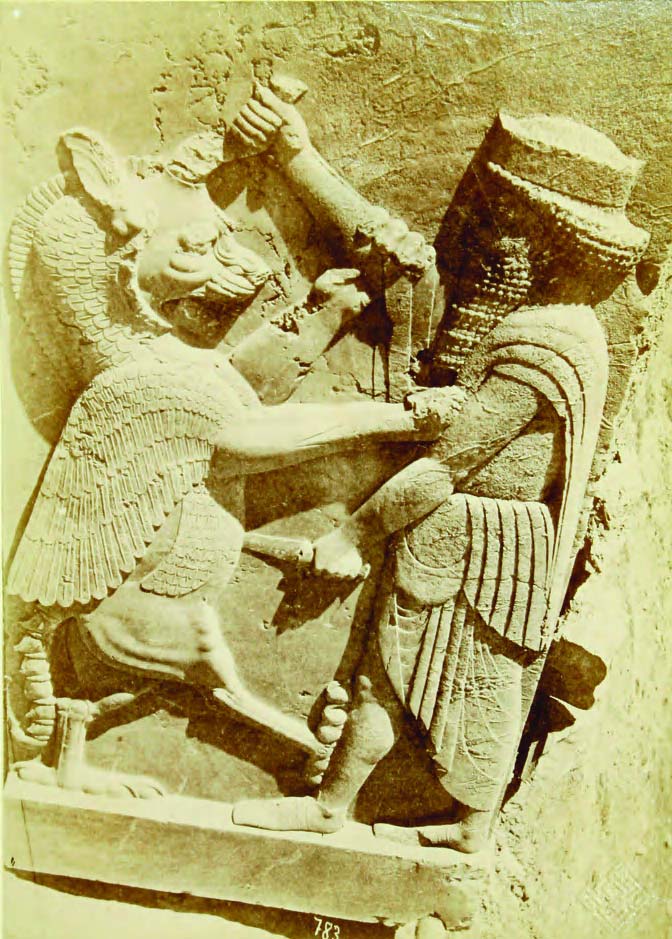

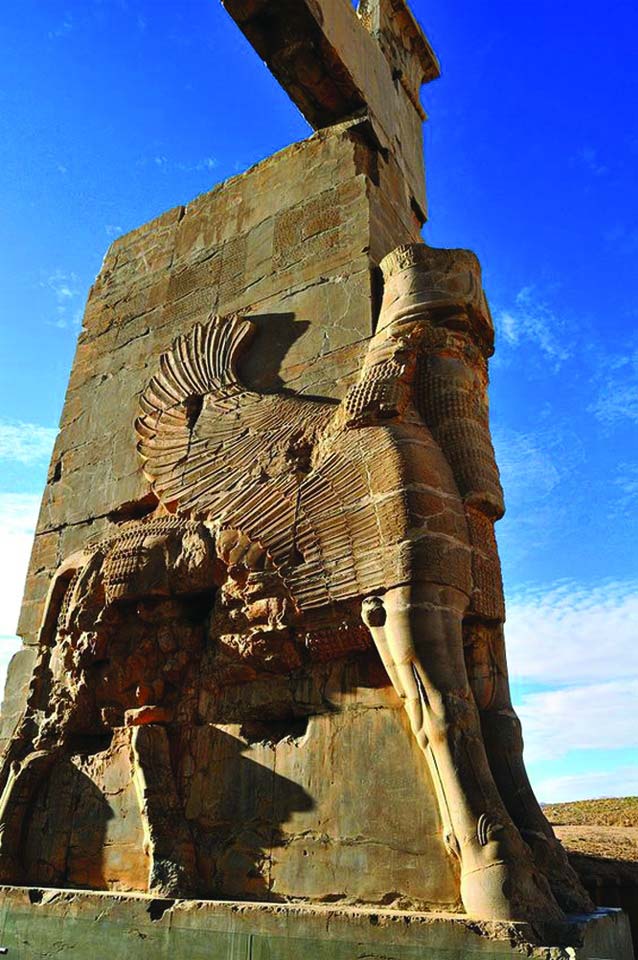

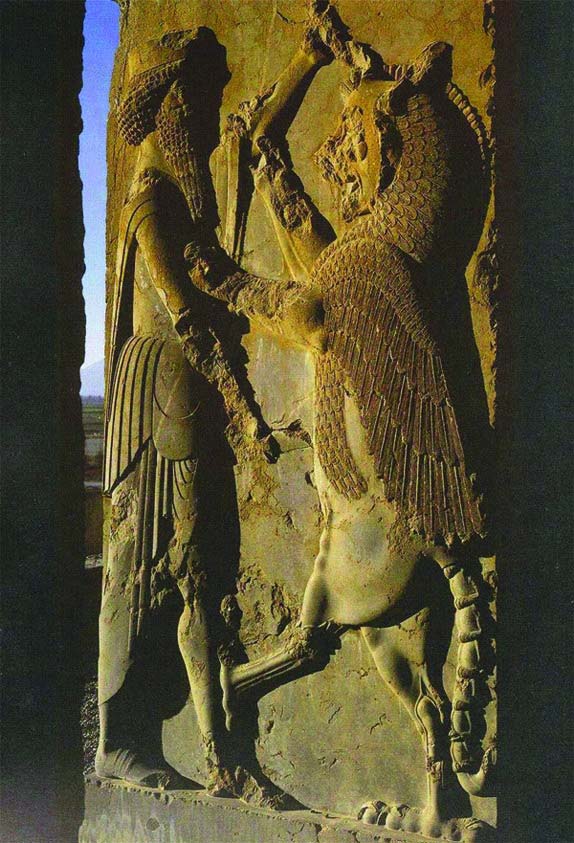

Travelers were familiar with the imagery of composite creatures and winged animals in their local cultures. In this symbolic art, which represents the final common realm of the human spirit, we see the resurgence of ancient patterns. Some of the motifs in Persepolis, particularly those repeated at the entrances, invite a renewed attention. Our focus is on the motifs where the act of stabbing occurs; as mentioned in previous lectures, “drita” in Old Persian means to cleave or split. 19

This verb also appears in modern Persian as “dareedan,” meaning to tear or rip, retaining the same connotation. The older form in Old Persian, “druja,” derived from the root “ji” and “gi” and “gyan” (sacred life), has a contrasting meaning. The opposite term, “aži,” translates to falsehood or distressing the soul and mind. In the Iranian languages, these two meanings emerge as opposites: “druja” (falsehood), 20 and “drit” or “drita” (to tear), akin to the action of a sword or the sun’s blade that cleaves through darkness.

In the myth of the birth of Mithras, he emerges as a spark leaping from the heart of the stone, cleaving through the cosmic darkness like a flash of lightning. He acts as a mediator or savior (Sushiant) 21, cutting through the darkness to reveal a new order, establishing a new structure. This concept is expressed in a poem by Sheikh Mahmoud Shabestari, a Mu’tazili philosopher:

“The charm of the unparalleled world / Emerged like a reckless sage / He raised the banner in the city of goodness / Disrupted the entire order of the world.”

One of the characteristics of Iranian architecture is its ability to endow heavy structures with a spiritual quality. This imparting of transparency and lightness to walls and ceilings is achieved through the use of myriad colors, intertwined patterns, symmetry, and repetition. We find brilliant examples of this artistic nature in the works of the Persian school. The bas-reliefs in Persepolis and Susa were all colorful, and there are outstanding examples of glazed wall decoration in the Apadana Palace at Susa.

The “rand” (mystic wanderer or free spirit) as depicted in the works of Shabestari, Hafez, and Omar Khayyam, aligns closely with the heroic and luminous figure described in the philosophy of the illuminative sage Sohrevardi. This figure is represented as a being of divine light in the esoteric tradition, and the concept of “piety” (or “parsayi”) 22 has evolved from the Gathas of Zoroaster to the poetry of Hafez.

In the gateways of Persepolis, we repeatedly encounter the image of a Persian hero or sage engaged in battle with a multi-limbed creature. This seems to represent the hero’s struggle against an ancient and mythical awareness standing before him. This creature appears in various forms: sometimes as a bull-shaped entity (symbolizing the earthly realm), with the paws of a lion (symbolizing dominion), and wings like an eagle (symbolizing celestial power). It is depicted with an animal head and lacking human intellect, and occasionally it has a scorpion-like tail as a symbol of harm. In all these depictions, the hero or sage uses a dagger (the golden sword) to cut through or “dritte” the creature. This action signifies a rupture and the revelation of a new level of consciousness for the hero or sage on the path to perfection.

The embodied image of this new level is represented by the pair of monumental figures standing at the entrance gate of Persepolis. These colossal stone carvings combine all the mentioned symbols but feature human heads or are adorned with “wisdom,” facing west. At the end of the ritual, as the sun sets, the pilgrim observes the sun setting through this gateway, in a position described by Sohrevardi as the “Western Exile.”

The ongoing focus on this light can also be seen in the mystical alchemical rituals and in the more refined design of dome structures known as patkane (skylights). 23

The manifestation of the idea of perfection in the motif of the Faravahar emerges through the utilization and renewal of an ancient and familiar motif in the civilizations of this region: a human figure with two wings, embodying the divine qualities that elevate and perfect him, stands within a temporal circle, holding a ring as a symbol of covenant and steadfastness.

Suhrawardi employs the term Khoreh in the context of the special angel of humanity, presenting a symbolic depiction of a being with two wings—one of light and the other of darkness. It is known that Khoreh or Khorreh means “divine glory” and also refers to the “east.” These meanings are interconnected in this philosophical framework because Khoreh represents the dwelling of the “radiance of glory” in the soul of the heroic or virtuous individual. According to Henry Corbin, the best examples of such exalted heroes are the legendary kings like Bahram, Fereydun, and Kay Khosrow, “whose souls are like fire temples.”

Suhrawardi reinterprets these terms with all their previous layers of meaning.

In the gateways of Persepolis, we repeatedly encounter the depiction of a hero or sage engaged in conflict with a composite creature. It appears that the hero is battling an earlier, mythological consciousness embodied by this creature, which presents various forms in different depictions. Sometimes this creature has the body of a bull (symbolizing the material world), with the claws of a lion (indicating dominion), and the wings of an eagle (representing celestial power). The creature is often depicted with an animal’s head and lacking human intellect, and occasionally, as a symbol of the fallen state, it has a scorpion’s tail. In all these representations, the hero or sage is depicted using a dagger (the golden sword) to pierce or cut through this creature or ancient awareness.

The pair of massive rock reliefs standing at the entrance of Persepolis represent figures of heroes on their path to perfection. Here, familiar images are once again utilized, but they acquire new meanings within this novel framework: composite beings, this time with human heads or adorned with “wisdom,” facing west and gazing upon the sun, which, centuries later, would be referred to by Suhrawardi as “Gharbat al-Gharbiya” (the Western Exile).

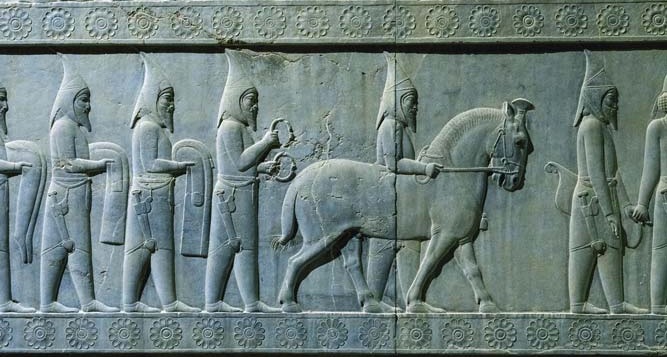

The scene depicted on the staircase of the Apadana Palace at Persepolis stands as one of the most significant historical records for tracing the evolution of consciousness. Here, an “idea” is carved into the stone, an idea that still seems ambitious even in today’s world: the gathering of representatives from twenty-three diverse peoples from all corners of the contemporary world: from the heart of Africa, to the northern shores of the Mediterranean, to the plains of the Indus and the far-off lands of Central Asia.

One might still ask today what preparations in thought and what practical infrastructures were needed to achieve such a gathering. How far had the group from the central African lands traveled to be present at Nowruz in this realm? And had they ever encountered anyone from the land of Sogd before this? Had the one from the Indus plains ever heard the language spoken by the people of the Mediterranean coast?

The key point in this depiction is the emphasis on an achievement that, within this framework of consciousness, was more than any other source of pride and was chosen among all possible options for recording and showcasing.

— There were numerous other possibilities: for instance, scenes of the conquest of powerful neighbors, the burning of massive fortresses, the acquisition of valuable treasures, banquets and revelries of rulers, or colossal statues of gods—

Let’s examine the behaviors: Those depicted are turning their heads towards each other in a gesture of conversation; the space between the stone faces clearly shows two-way communication. There is no sign of the ironclad discipline and the heavy, countless statues of the Emperor’s army in the tomb of China’s first emperor; no trace of the deathly silence of the pharaohs staring fixedly in their supposed eternal life; nor are they dressed uniformly in the manner of Roman citizens.

Here, we have a colorful and vibrant space full of dialogue and diversity. It is inviting, seemingly insisting that it accommodates everyone. Each person represents a specific place, and the designer highlights their affiliation through the details of their clothing, adornments, and the diversity in their faces. Each group is portrayed in its unique attire and ornamentation, making it possible to identify their ethnic and regional affiliations today. The guests are equal. The various ethnic groups are accepted with their differences and are valued and celebrated. Unity is defined not by eliminating diversity but by embracing and even taking pride in it.