An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

In the previous lecture, it was briefly mentioned how climate, in terms of its cooperation with humans in obtaining food, access to fresh water sources, providing the experience of different seasons, and even uniformity or, conversely, internal diversity of nature, might be conducive to the emergence of various cultures. It was also noted that the possibility of easy or difficult interactions with other tribes and groups, exposure to mixing and sharing discoveries, as well as experiencing differences and contrasts, or, conversely, being isolated and separated from others, can influence the nature of the inhabitants of lands. This last point is particularly important when we know that the fate of every human civilization has been largely dependent on the exchange of discoveries and the trade of innovations and ideas. In some ecosystems, it has been fortunate for the inhabitants that the opportunity to distribute experiences has been available, leading to greater accumulation of knowledge, culture, and technological advancement.

However, there are many examples to the contrary. In an exaggerated example where it seems the hand of fate cruelly created a laboratory environment, we see that the complete isolation in the continent of Australia kept a small group of people, undoubtedly as intelligent and capable as the ancestors of the inhabitants of other continents, in the Stone Age in terms of culture and technology until the seventeenth century when they encountered European invaders; without any metal tools, without the possibility of animal husbandry or plant domestication, agriculture, or food production.

Thus, by focusing on the various aspects of human life, one can compile a long list of minor and major elements that, each to some extent and during different periods of history, have caused the sharing and blending of the inhabitants of a land, aligning them with each other in various ways. As a result, they not only live on the same “land,” but also in a unified “world,” receiving and nurturing a similar “meaning” of the world within themselves, creating and inventing within a similar system.

The emergence of this “world” is a crucial matter that, if it occurs within a group, depending on the power and fertility of its idea, can become a “womb” capable of nurturing the seeds of awareness. And since historical thought does not remain confined and enclosed within its circle, the light of this awareness, again depending on its capability, can shine like a ray upon its surroundings, illuminating even vast expanses.

With these explanations, we reach a stage in tracing the course of history where the general headings that encompass all civilizations and all the people of the world, studying humans as humans, become fewer. Beyond a certain point, in studying the nature of each founding culture, the influential factors must be recognized and researched with attention to their specific characteristics and in accordance with the culture under study. As previously mentioned, the complex combination of climatic conditions, along with historical experiences and living resources, leads to the formation of different “social contracts” among human groups.

Today, we understand social contracts through concepts discussed by modern scholars like Hobbes, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and others. However, we should not overlook that the core concept of the social contract is rooted in ancient foundations that have manifested among human groups throughout history. This can be seen in the form of treaties and pacts between tribes, such as the Old Testament; or in more subtle forms, such as legitimizing power, establishing rituals and belief systems, creating calendars, and the countless occasions on which a group of people have reached an agreement, given it meaning, and derived meaning from it.

In studying a long-standing historical land like Iran, understanding the prevailing social contracts and the living conditions that led to the establishment of such contracts over a vast expanse is of great importance. This brings us closer to a better understanding of the “nation of Iran.”

By “nation,” as mentioned in the previous lecture, we mean the emergence of a secondary identity that operates beyond ethnic and tribal identity, uniting diverse tribes and races.

Through such reflection, we might approach an understanding of one of the philosophical questions of history regarding Iran: it is often considered that the birth of nations is the result of the emergence of a central government that unifies human groups through the exercise of power. The study of European history reveals the historical trajectory of such a phenomenon. European history, after the fall of the Roman Empire, began with the establishment of the Holy Christian Republic, and then, in a historical process, national states emerged one after another until the nineteenth century, under which the nations of France, England, the Netherlands, Germany, and others were formed.

A tangible example, and one historically closer, is seen in the formation of such nations in the United States of America, where a new nation was born with the adoption of the Constitution under a central government.

However, in the culturally and historically rich land of Iran, the process of nation formation did not occur as described by modern Western scholarship based on European experience. Here, we have witnessed an inverse process. What we call the “nation of Iran” is the product of shared experiences over a long period, within a context of extensive exchanges, that aligned various peoples from different tribes and ethnicities, making them linguistically and culturally cohesive (in the broadest sense) and united. The establishment of central authority and the formation of a centralized power occurred later, on this foundation.

The result of such a type of covenant has been that in Iranian history, the prolonged absence of national sovereignty or fundamental upheavals in power structures did not lead to the collapse of the nation. Here, the “national covenant” has endured, or at least been remarkably resilient.

Iranian history is replete with numerous instances where, after the collapse of central authority, the ambition to establish a national state, based on the enduring national covenant, would resurface from various quarters. After the acceptance of Islam, during the Islamic Caliphate, Iran was the only region where new national states were established (e.g., the Buyids, Tahirids, Samanids, etc.). In the long periods when there was effectively no single, comprehensive national state, the shared culture that linked regions from Transoxiana to Ctesiphon not only remained intact but also renewed itself within the framework of a new religion and ideology. Indeed, some of the renaissances or cultural revivals in various fields of science, philosophy, art, literature, and architecture occurred during these periods and in the absence of a national state. We will discuss these in detail in future discussions.

In regions beyond today’s political borders, despite the frequent severance of connections and the efforts of ruling powers to erase cultural identities through measures such as changing borders, forced relocations, and other means, the cultural bond persists in the underlying layers of culture. This is evident in practices such as celebrating festivals, using traditional calendars, employing musical creation systems, visual motifs, and maintaining language. As Dr. Javad Tabatabai puts it, Europeans are “state-based” nations, while Iran is a “nation-based” country.

Regarding the nature and reasons for the types of covenants that have prevailed in this land, we must seek answers through exploration. Historical evidence shows that the cultural world of Iran existed before the political and even the linguistic Iran emerged.

In ancient times, which we try to identify based on its signs and tangible products, the dissemination of significant achievements in the provision of life necessities, along with shared beliefs and ideas, led to the emergence of a deep connection among the inhabitants of the expansive Iranian plateau.

“He who plants grain plants ‘Ashah.’ He cultivates it increasingly and increasingly. He strengthens the Mazdaic faith so that it can endure a hundred prayers.”

Avesta, Vendidad, Fargard 3, Section 3

It seems that “taming” and, at more advanced levels, “domesticating” nature are among the shared achievements of humanity, practiced wherever the opportunity arose, either inspired by neighbors or tested independently. However, the unparalleled growth of agriculture and subsequent sedentism in the proliferating communities of Western Asia, and the rapid spread of these achievements to surrounding regions—extending to Europe, North Africa, the Indus Basin, the Indian subcontinent, and ultimately interactions with the Far East—requires further explanation.

Within the political borders of today’s Iran, archaeological exploration and studies in relation to the vast amount of raw materials available are very limited. The scientific excavations and studies conducted are old and pertain to a time when contemporary knowledge in material testing and interpreting historical clues was less advanced.

Nevertheless, from the existing evidence in archaeological excavations, as well as research studies on traditional Iranian historical texts and oral narratives, meaningful traces of the beginning of this long and tumultuous story can be found. These findings may be revised or refined with further discoveries.

We will first explore the archaeological achievements and the analysis of ancient societies at the beginning of settled life, and then refer to examples of narratives related to the origins in traditional Iranian history, ancient texts, and neighboring cultures.

It appears that the climate of Southwest Asia, with relatively mild winters and hot, dry summers, was conducive to the growth of plants that were more easily domesticated. The region’s nature was filled with annual plants that, unlike forest vegetation, primarily invested their energy in producing seeds rather than developing thick trunks and expanding branches and foliage. Human selection and intervention in choosing seeds for cultivation often focused on enhancing the “weak points” of a species. This process can be seen as reversing the natural selection process typically observed in the evolution of plants. It led to the proliferation of species with traits favorable for human consumption, rather than necessarily beneficial for the plant’s natural survival. For example, cultivating varieties whose pods do not split open after seed ripening, or seeds that do not spontaneously detach from the stalk and fall to the ground, or fruits that are excessively large and heavy. 1

The era of domesticating large mammals began with sheep, goats, and pigs, and ended with the camel. Despite all human experiences and advancements in knowledge and capabilities from around 2500 BCE onward, no decisive new examples were added to this list. This almost indicates that our ancestors domesticated all animals that could be domesticated or were potentially domesticated at the very beginning of settled life. 2

The Agricultural Revolution

By entering into the experience of agricultural life, humanity embarked on the path of its most fateful era in history. Each of the foundational civilizations in the history of thought entered this stage at different times and under varying conditions. The issue of the timing and sequence of entering the Agricultural Revolution is not so much the focus here (in recent centuries, our understanding of this has continuously evolved with new discoveries and the excavation of new archaeological sites — although these changes typically enter the grand narratives in our minds or even in public historical texts slowly).

In any case, merely discovering the firsts and historical sequences does not shed much light on our focus, which is to uncover the specifics of the differences in foundational texts within each cultural hub. What we are interested in here is an aspect of this topic that shows how stepping into this path initiated a fundamental transformation in the awareness of peoples. Relative to the lived experiences in each cultural center, a specific type of worldview emerged, giving rise to unique questions and efforts to answer them, which led to the formation of the early stages of history in each center (refer to the concept of the “poetic human” in previous discussions).

Today, with the extensive research conducted on the Agricultural Revolution, we have a wealth of knowledge about this period in various regions of the world. However, important questions still remain unanswered.

Findings to date suggest that the first experiences related to the cultivation of plants began around the 12th millennium BCE in the region known as the Fertile Crescent—encompassing parts of Anatolia, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, and Iran. Evidence of simultaneous beginnings of cultivation is also found in other regions, such as the Anu civilization in Central Asia. 3

Alongside efforts to cultivate edible plants, animals were domesticated one by one from around the 10th millennium BCE. During this process, the most important animals that continue to be sources of food and labor for humans, and whose by-products are crucial in various technologies—namely: cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, and dogs—were domesticated in this very region. The dog is a unique example that was also domesticated independently in other areas. Although the horse is believed to have been native to the northern steppes of the Black Sea, some of the earliest evidence of its domestication dates back to around the 4th millennium BCE in eastern Iran (Sistan).

The geographical environment of Western Asia, with its great natural diversity and high elevations in the Alborz and Zagros mountains, as well as the lowlands and the proximity of cold and warm climates in many areas (Iran, in this regard, has a unique position), was conducive to the growth of plants suitable for cultivation and the domestication of mammals. Perhaps most importantly and determinatively, the absence of insurmountable natural barriers allowed for the mixing and exchange of achievements. Since each new innovation is built upon previous inventions, the dissemination of experiences and knowledge has been even more crucial than their initial creation.

The Asuric Tree is a poem written in Parthian, but its content suggests that it is based on an older composition. The story revolves around a debate between a tree and a goat:

[Tree]

I am superior to you,

In many ways.

And among the trees of the land of Iran,

None are of my stature;

For the king eats from me;

As I bring forth new fruit.

They sweep from me,

To grind wheat and rice.

I am the storehouse for the farmers,

And the shoes for the barefoot.

They make ropes from me,

To bind your legs.

They make wood from me,

To rub your neck.

[Goat]

Listen, oh tall demon!

The special religion of Zoroastrianism,

Taught by the kind Hormazd,

Can only praise me, the goat.

For they make milk from me

In worship of the gods.

My skin becomes a water container,

In the fields and deserts.

And they make manuscripts from me,

And scrolls of the court.

They make bowstrings from me,

To bind the bow.

And they make fodder from me,

For the merchants.

Translated excerpts by Mahyar Navaei

Contrary to what might be commonly perceived today, agricultural life initially had serious drawbacks, such as hard and extensive labor and limited diversity of life. Additionally, over time, other disadvantages emerged, including the transfer of diseases from animals to humans and the spread of contagious, fatal diseases in dense populations. However, this population density, a direct result of food production and storage, created the basis for the specialization of labor, which in turn led to the invention of new techniques and tools.

All these changes eventually led to the formation of more complex social and political structures. Almost all of the remaining civilizational achievements emerged in the region known as the “Golden Rectangle,” which stretches from the Danube and North Africa on one side to the Indus Valley on the other. These achievements include the rise of large cities, the invention of the wheel, the development of writing, metallurgy, advanced irrigation methods, and the rise of the first empires.

With this explanation in mind, let’s take a step back and consider one of the most complex questions in archaeology: why did humanity transition from a natural state of survival through hunting and nomadism to agriculture and food production? This question becomes more challenging to answer when we recognize that most experts today, contrary to previous interpretations, believe that early agricultural life was much more difficult than hunting. Certainly, early societies were unaware of the secondary benefits and outcomes of settled life.

“It might be possible to understand the mechanisms of domesticating plants and animals, but it is challenging to comprehend the motivations behind why people undertook such tasks. The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture is one of the oldest, most complex, and significant questions in human history.” 4

“A cornfield is as much a product of human creation as a microchip, a magazine, or a missile. It has only been in the last 11,000 years that humans have cultivated their own food. Agriculture began independently at various times and places: in Southwest Asia (wheat and barley) around 8500 BCE, in China (millet and rice) around 7500 BCE, and in Central and South America (corn and potatoes) around 3500 BCE. The practice of agriculture spread from these three main centers to all parts of the world and became the most crucial means of food production for humanity.” 5

“Agriculture completely overturned the hunting-gathering way of life that had provided food for humans for tens of thousands of years, leading people to abandon the diverse and relatively comfortable life of hunting and gathering in favor of a life filled with toil and hardship.” 6

“If we take the 150,000 years that humans have existed as one hour, it is only in the last four and a half minutes that humans turned to agriculture, and agriculture has only become the primary means of food production in the last minute and a half. The shift from gathering food to growing food—from a natural method to a technical means of food production—occurred only recently and abruptly.” 7

“Even today, thousands of years after the first farmers began the process of domesticating plants and animals, humanity remains a farming species, and food production is the primary occupation of humankind. Agriculture employs 41 percent of people, more than any other activity, and covers 40 percent of the Earth’s land area (about one-third of this land is used for growing grains and about two-thirds for growing animal feed).” 8

It seems that “taming” and, in more advanced stages, “domesticating” are among the shared innovations of humanity, tested independently or inspired by neighbors wherever the opportunity existed. However, the unparalleled growth of agriculture and the subsequent shift to settled communities in the proliferating societies of Western Asia, and the rapid spread of these achievements to surrounding areas—Europe, North Africa, the Indus Basin, the Indian subcontinent, and ultimately exchanges with the Far East—require further explanation.

This triumph of sedentary agriculture and its dominance over other forms of subsistence is not self-evident or universal. For example, although agriculture developed independently on the American continent, as far as we know, agricultural societies there developed very slowly alongside hunter-gatherer populations. Until the arrival of European settlers, a significant percentage of the nomadic population had never abandoned their way of life to join their agricultural neighbors. It seems that the mere availability of abundant plants and domesticable animals, combined with the potential for knowledge and technology exchange, does not alone provide a convincing answer to why agriculture spread explosively in this region. Some researchers believe that on this natural hardware, a kind of software consisting of rituals and ideas emerged, directing the use of natural resources towards subsequent outcomes.

The development of sedentism is such that around 5400 BCE, numerous settlements of early agricultural societies emerge almost simultaneously in a broad area from the plains of Hungary to Central Europe, spanning from western Poland to the Netherlands. These societies are characterized by their decorated pottery. 9

“Now, if we look more closely at the developments of this period in the region in question, we find points that may support this view. Relatively recent research by Neolithic archaeologists shows that after the agricultural revolution and the establishment of large, densely populated cities—evidenced by multiple layers in their remains indicating that the inhabitants lived in the same place over several periods (e.g., Çatalhöyük in Anatolia)—the growth of agricultural societies in this region gradually slowed from the beginning of the 7th millennium BCE. This period saw a decrease in urban populations, the quality and order of architectural settlements, and the sophistication of tools. Instead, nomadism and hunting, which had existed alongside agriculture, gained greater prominence.

Then, in a new wave starting around the middle of the 7th millennium BCE, many new settlements emerged, not only on old habitation sites but also extensively on fresh, virgin lands. These new settlements had smaller populations compared to the earlier cities, but their numbers were significantly greater. The techniques of domesticating animals and plants spread across a vast region from Iran, Iraq, and Anatolia to Greece 10 and North Africa. A distinguishing feature of this new wave of sedentism is the appearance of decorated pottery across these regions.

“What expanded the reach of the Indo-European language family to such an extent was the influence of agricultural culture from this region among various peoples. Linguistic findings suggest that the spread of language families was accompanied by the diffusion of agriculture. Today, nearly 90% of the world’s population speaks a language that belongs to one of the seven language families rooted in two agricultural centers: the Fertile Crescent and parts of China.” 11

Recent evidence and experiments suggest that in this new wave, people equipped with agricultural techniques migrated to new lands and brought with them both improved seeds and domesticated animals wherever they went. One piece of evidence supporting this is research indicating that any plant species originating from this region was domesticated only once, and all its products are derived from a common ancestor. This suggests that agricultural techniques spread from a single source, which necessitated extensive and rapid exchanges among the peoples of the region that must have lasted for millennia.

The origin of wheat, barley, beans, lentils, and many other cereals and legumes, which spread rapidly across the ancient world—from Europe to northern Africa (Egypt) and even to China (where wheat and barley from this region were introduced around the 2nd millennium BCE)—were the domesticated plants of this region. 12

This is a distinctive feature that separates the transformation that occurred in this region from other parts of the world, where efforts to domesticate plants were also underway. For instance, in the Americas, the domestication of some plants, including maize, was the result of efforts by several separate societies in different regions, each independently domesticating varieties of the same plant. It is evident how such a situation would have significantly slowed the development and progress in these societies.

“Recent evidence and experiments suggest that during the wave of agricultural expansion from the Near East, people equipped with agricultural techniques migrated to new lands and, wherever they went, took with them improved cultivable seeds and domesticated animals.”

Recent research indicates that in Western Asia, the spread of small groups equipped with agricultural knowledge towards new lands was not a racial migration (like the Aryan migrations) but rather a movement of a culture and lifestyle. The indigenous peoples and previous inhabitants of these new areas gradually joined and adopted this new practice.

Some archaeologists, including Jacques Cauvin 13, emphasize the significant role of a ‘new idea’ in this major historical movement. According to him and other researchers, the widespread adoption of agriculture around the mid-7th millennium BCE should be explained not merely by the practical advantages of agricultural economics over nomadic economies but by the spread of a new value system and ideology. This system transformed people’s beliefs about the value of labor for land development, cultivation, and settled living. Among these scholars, Mary Settgast is also notable for her contributions. 14

Going a step further, these new ideas are found to be very compatible with the teachings in ancient literature, and some see the source of this significant leap in the growth and proliferation of Neolithic cities as aligning with Zoroastrian teachings. Settgast proposes the hypothesis that perhaps we should take the Greek historians’ claims about the antiquity of Zoroaster’s life seriously. 15

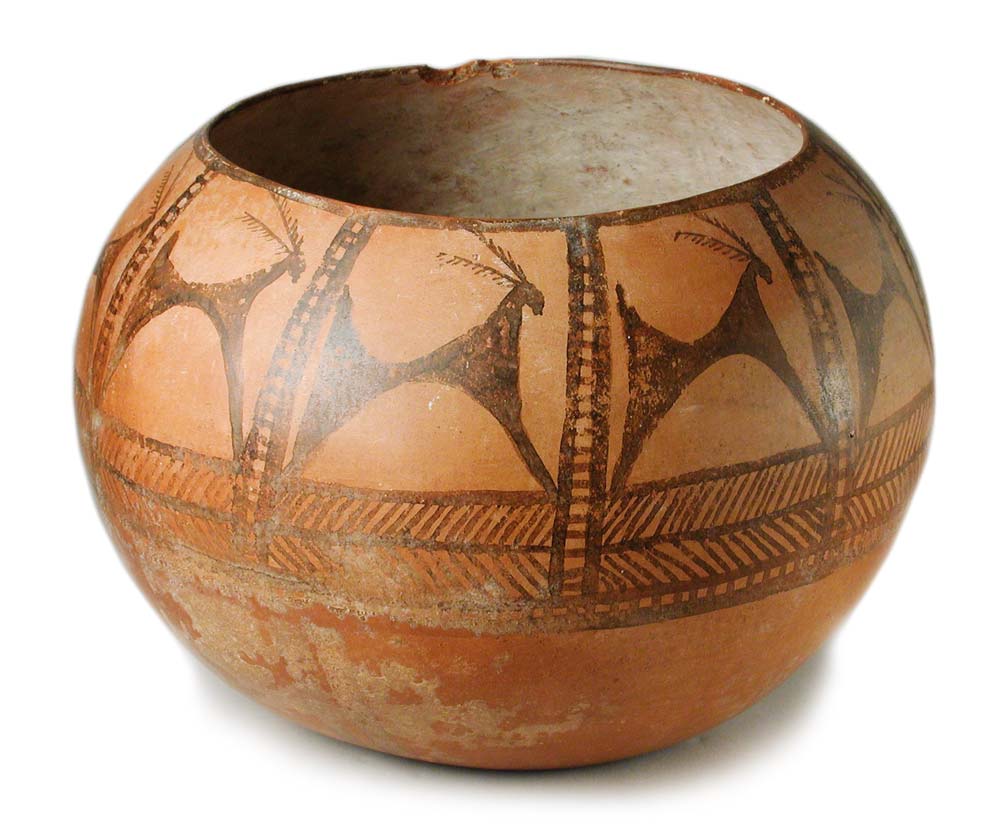

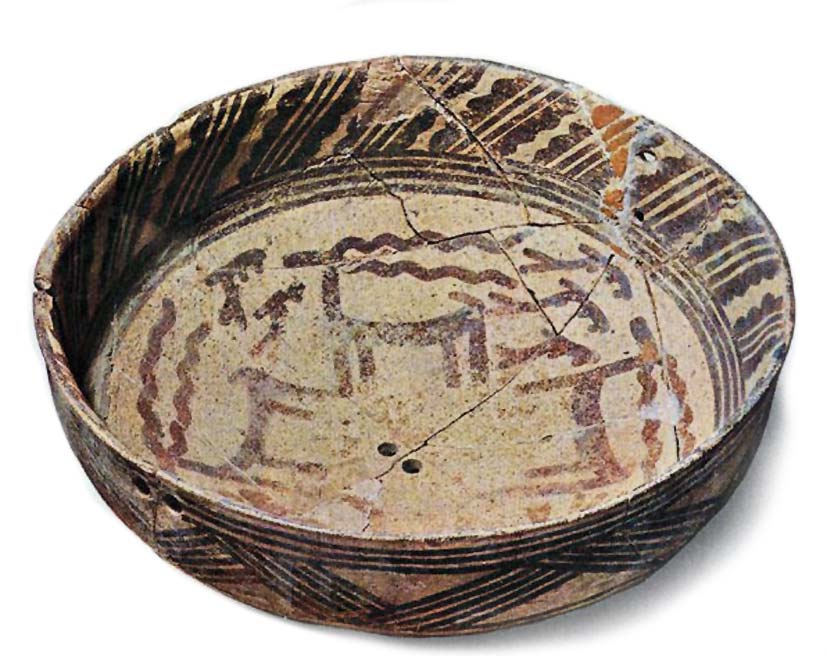

Pottery that marks the spread of sedentary life features black-brown patterns on an orange-red background. These often include depictions of domesticated animals, spiral motifs, rotational patterns, swastikas, black-and-white checkered surfaces, and the double-headed axe motif symbolizing two opposing forces in one entity. The “swastika,” a widespread archetypal human symbol, appears abundantly on late 7th millennium BCE pottery. This motif may represent a complete world created in Iranian mythology, where the midday sun is stationary in the middle of the sky. Conversely, the sun-chariot or wheel of the heavens, along with various rotational patterns, might symbolize the beginning of the sun’s movement, marking the start of time in the texts of this culture.

Evidence of this shift in perspective can be seen in changes to previous burial rites, such as the practice of burying skulls and bull horns, which are no longer present in these new settlements. Additionally, the design of the villages contrasts with earlier sedentary communities, which were organized around a central altar or temple; in these new settlements, there is no dependence on a sacred place, and no signs of altars or temples are found. Settgast relates this to the spirit of Zoroastrianism, where “the object of reverence is the world itself or the cosmos.

Another noteworthy point is that the reduction and sometimes disappearance of spears, arrows, and battle tools in the trenches from the post-agricultural revolution period across these new settlements indicate a shift away from a lifestyle based on warfare and raids. Settgast explains this by comparing the Gathic literature with Vedic stories, which belong to a much earlier period in terms of time.” “The heroes praised in the Vedic hymns are constantly stealing cattle and reclaiming stolen cattle, 16 which depicts a kind of primitive, tumultuous life and value systems defining heroism, strongly opposed in Zoroastrian teachings. The exploration of these newly discovered villages shows that for long periods, and in some places, including the Iranian plateau, for up to two millennia, agricultural blades significantly replaced warheads.

Another characteristic of these new settlements is that in many areas, lands have been cultivated that require artificial irrigation. This roughly coincides with the drought period when the vast lakes in central Iran begin to dry up, and the central desert of Iran gradually emerges, which we will discuss later. The effort towards irrigation also reminds us of the Vendidad teachings, which emphasize that the place where the land finds the most happiness is ‘where the righteous man plants the most wheat, plants, and fruit trees, where such a person irrigates the dry lands and drains the wet lands. 17

The collection of designs on these pottery pieces is, in some respects, different from the images created in other cultures. In these designs, there is no trace of the illusions and totems of the shamanistic era, nor is there any concept of a monstrous creature or an incredible myth, which reveals a new relationship established between humans and the world.

Moreover, despite the numerous production sites, these designs indicate a shared system of consciousness.

Apart from such views, the contemporaneity of Zoroaster’s life with this very ancient agricultural transformation in the mid-seventh millennium BCE is a subject that may find more evidence for its confirmation or refutation with more extensive research. Likewise, answering the question of whether the name Zoroaster refers to a specific individual in history or to multiple individuals in different periods requires further historical investigation.

What is noteworthy, however, is that we can perceive here the antiquity and depth of a formative culture that has significant outward manifestations, and perhaps in later centuries, refined achievements of this culture were incorporated into Zoroastrian texts. 18 What is clear is that a new value system underpinned this great transformation in human lifestyle, which forever changed the other aspects of his life.

Stability and extensive interactions led to the accumulation of technology and techniques, spreading vital methods for progress everywhere: pottery firing, metal smelting, irrigation techniques, and others developed.

As mentioned, one of the signs of the spread of agricultural groups into new territories is the appearance of intricately crafted painted pottery. Pottery quality significantly improved in several of these new settlements in the millennia following its invention. This advancement, along with the idea of promoting urbanization, spread widely. In the Iranian plateau, the Cheshmeh-Ali civilization, which emerged in the mid-seventh millennium BCE in the area of modern-day Rey (Raga), was connected with the Sialk civilization as well as Tepe Zagheh and the cities of southwestern Iran.

In the Cheshmeh-Ali workshops, significant advancements were made in producing thin, eggshell-like pottery that was fired at high temperatures and, despite its delicacy, had remarkable durability and strength. A distinctive style emerged that spread to other centers. Similarly, in northern Mesopotamia, in Hassuna and Halaf, and in the Zagros foothills, fine painted pottery was being produced.

Using material tracing methods, we know that Hassuna pottery was distributed up to 800 kilometers away from its place of origin.

There is no evidence anywhere that these fine painted potteries were used for cooking. Their association with this new agricultural culture everywhere convinces us that they were likely in service of propagating the same ideas and rituals that promoted agriculture. The ritual use of vessels is seen in various cultures around the world, and perhaps one of the oldest examples of this is the spreading of the Yasna or Sena cloth in Mazdean rituals

The degree of complexity in the designs and the finesse of the pottery products vary from region to region, but what draws our attention is the pictorial system engraved on the pottery. The designs used are almost similar from the Indus Valley to Greece and have persisted and perfected for at least a millennium. The images on these pottery pieces reflect a new intellectual order that has been recorded and transmitted through the medium of its time, acting as a tool for conveying, expressing, and preserving an intellectual heritage.

This collection of designs differs in some respects from the images produced in other centers of human habitation. In these designs, illusions and totems of the shamanistic era are absent, and there is no trace of monstrous creatures or incredible myths. This highlights a new relationship established between humans and the world.

Within the Iranian plateau, the continuity of the tradition of painted pottery lasted nearly three millennia; much longer than in other regions, which each took a different path over time, some fading completely. The pottery culture in Mesopotamia endured for a millennium until the rise of the Ubaid civilization, which laid the groundwork for Sumer. In the Iranian plateau, the continuity and internal evolution of pottery designs, along with their expansion into jewelry, textiles, stone carving, plasterwork, and more, laid the foundation for the pictorial culture of the flourishing civilizations of later millennia.

Western historiographies typically begin with the images from the Lascaux caves. Cave art, found in all early human habitats—from Europe to Australia, Africa, and the Americas, including Iran—represents universal and archetypal expressions of cosmic awareness. For studying Iranian art, the emergence of these pottery designs marks a decisive break that can be considered as the beginning of Iranian art history and the starting point of the unique path it has taken.

Now we turn our attention to the Iranian plateau, located in the middle of the newly established settlement areas of the golden rectangle. Looking back a bit: geographically, during the last Ice Age, when the freezing of waters on land had caused sea levels to drop significantly, the Persian Gulf was almost dry, and the Karun River in Khuzestan joined the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, flowing into the Arabian Sea near the Strait of Hormuz. During this period, people mainly resided in the southern lands, including what is now the Persian Gulf, and then, with the gradual warming of the climate and the slow rise in sea levels, they migrated to higher lands.

The central Iranian lakes, which are now located in the current desert regions, were once full of water. The early urban centers, such as Tepe Sialk in Kashan, Tepe Hissar in Damghan, Shahr-e Sukhteh in Sistan, Tepe Yahya in Kerman, and many other significant cultural centers of the Iranian plateau that are now located in its most arid areas, were established during their flourishing periods in a green and fertile landscape alongside the central lakes.

Evidence indicates that the Iranian plateau entered a long period of drought after the end of the Ice Age, with its peak from the 8th to the 5th millennium BCE. 19 During this period, although the central Iranian lakes remained and were navigable, they gradually receded over time.

As noted, the scattered, sparsely populated settlements that spread across the plateau and beyond from the mid-seventh millennium were not reliant on dry farming in many areas. Studies indicate that from this period, methods for artificial irrigation of cultivated lands began to be developed. These techniques included canal construction, damming, and seasonal water storage, with the most notable achievement being qanat technology. In Iran, the oldest qanats still in use are over three thousand years old. 20 Qanat construction required the digging of long underground channels, extending several kilometers, and involved a significant amount of time. It necessitated collective effort, as well as the dissemination of calculation techniques and empirical knowledge of groundwater. The driving force behind this natural necessity for effort was the same intellectual framework that valued land development and imbued the struggle against drought with a meaning beyond mere daily and individual endeavor. This ethos is reflected in the continued determination to establish lush gardens in the driest regions of the land, a legacy that persists even into recent centuries.

In various ways, the material necessities of life contributed to the survival and flourishing of the idea of settled culture in the Iranian plateau. Despite the competition and conflicts among different cities that emerged after two relatively peaceful millennia, trade routes and pathways passing through numerous cities and leading to the markets of the East and West played a significant role in connecting these cities. At the same time, the achievements of each region were inevitably disseminated along these routes.

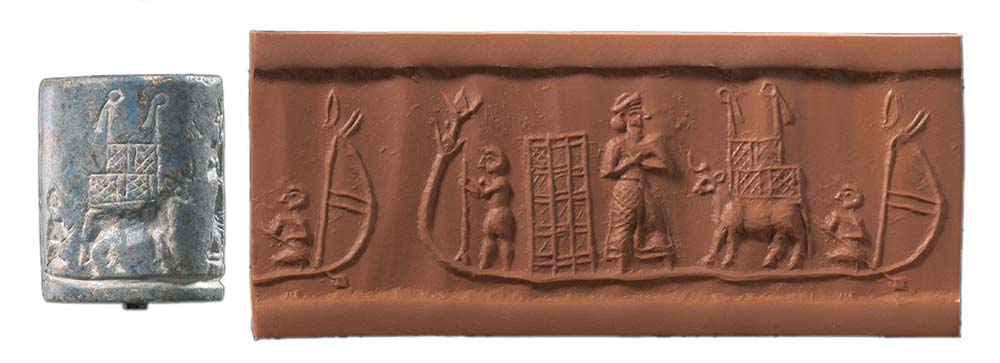

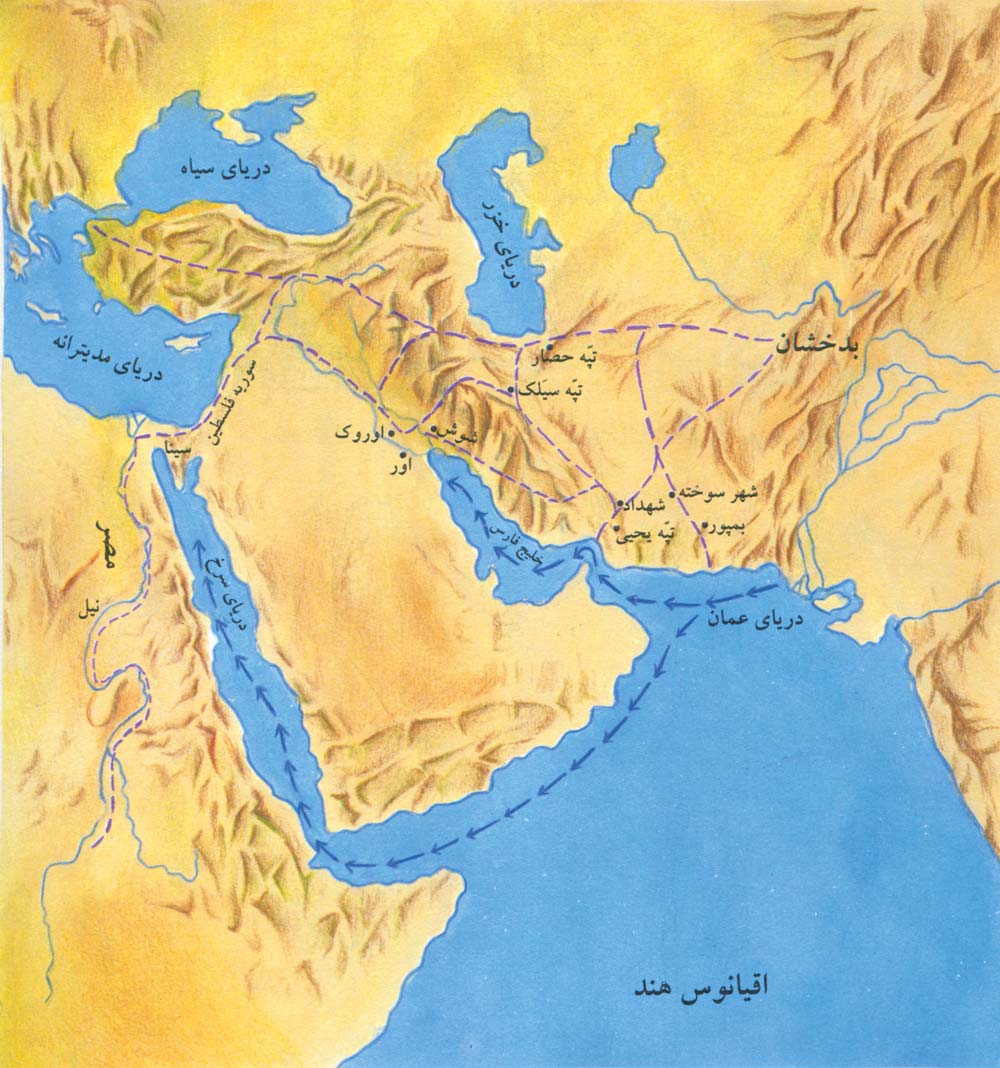

Central Asia and Iran were the sources of lapis lazuli and other precious stones, a special variety of copper and tin, as well as other products including medicinal plants and various dyes. 21

Goods such as lapis lazuli and turquoise from the eastern mines of the Iranian plateau were traded to Egypt. At the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE, lapis lazuli was a major commercial item of the Iranian plateau, sourced from Badakhshan 22 and possibly from central mines near Kashan. It was a highly sought-after commodity in the ancient world, processed at workshops along its trade route, either at Tepe Zagheh in Qazvin or at centers found in present-day Pakistan, and sold in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

In ancient times, copper, tin, gold, lapis lazuli, jade, agate, turquoise, and other valuable stones originating from Iran and Afghanistan were transported to Mesopotamia and Egypt. Additionally, cedar wood, plant oils, special dyes, and eye cosmetics were among the goods that were exported from the Iranian plateau to the markets of Egypt.

One of the main trade routes of that era was the route through Khorasan, which facilitated the overland transport of commercial goods from eastern Iran to Mesopotamia, and from there to Palestine and Egypt. Besides this route, there was another passage that included maritime transport of goods from eastern Iran to Mesopotamia and Egypt. This primary trade route passed through Tepe Hissar (Damghan) and Tepe Sialk (Kashan) and transported goods to Sumer, from where they were shipped by sea to Egypt.

The second trade route, known as the ‘Amo Road,’ began in Central Asia and passed through Samarkand, Bukhara, Merv, Sarakhs, Mashhad, Gonabad, Shahr-e Sukhteh, Kerman, and Tepe Yahya, reaching the Strait of Hormuz where maritime travel commenced. This trade route, utilized since the 3rd millennium BCE, connected with the first route and reached Egypt via the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, the shores of the Arabian Peninsula, the Red Sea, and finally to Egypt. Additionally, there was a third maritime route that entered the Indian Ocean from the Indus River and, after passing through the Arabian Sea, joined the aforementioned sea route to reach Egypt. 23

Evidence also suggests that the supply of metals to a wide region including Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Palestine was sourced from Iranian mines. This is supported by the presence of arsenic in the copper products found in these regions, which matches the arsenic levels found in ores from central Iran and the Caucasus. Such hypotheses existed even before the discovery of archaeological sites in Iran.

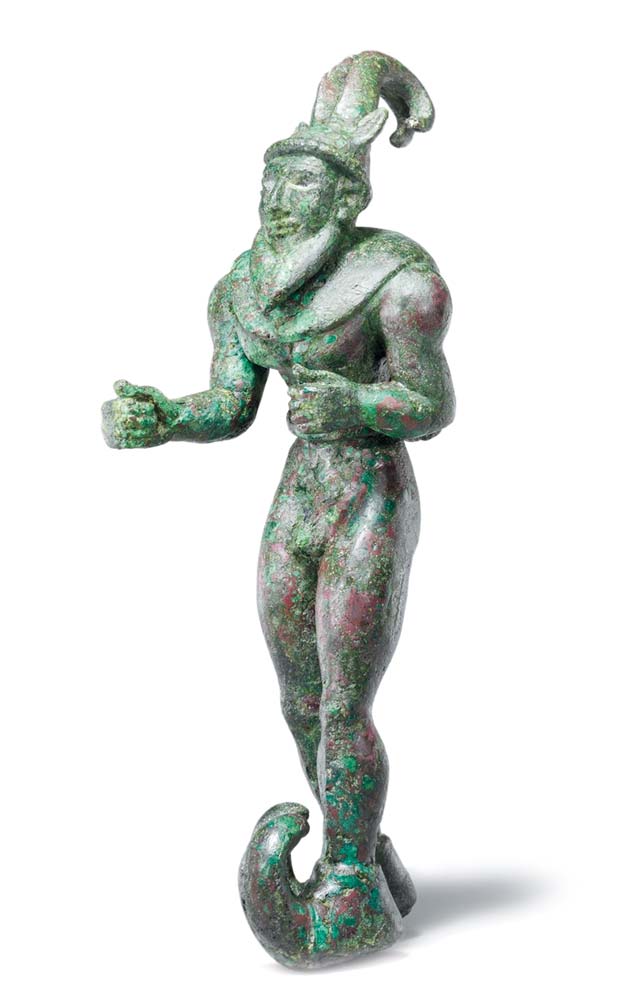

There is substantial evidence of advanced metalworking in the northern and western regions of the Zagros area during the 4th millennium BCE. The bronze artifacts from Lorestan date primarily from 2900 to the 7th century BCE. The stylistic diversity indicates the presence of multiple workshops in this region. The objects were cast using molds and were further finished through engraving and repoussé techniques. These methods show similarities with some cultures of Mesopotamia, including Kirkuk, as well as Urartian metalworking (Armenia). Additionally, stylistic connections can be observed between these artifacts and those from Sialk, Amlash, Hasanlu, and Khorvin. 24

The technology of the kiln did not end with the firing of high-quality pottery at elevated temperatures. In the 1970s, one of the oldest industrial complexes of the ancient world was discovered in the Arisman region, between Natanz and Kashan. This area, which covered ten thousand square meters in 4000 BCE and expanded to twenty thousand square meters in later periods, was filled with pottery, kiln remnants, and slag from metal smelting, particularly copper and silver.

Although the Arisman metal smelting industry is one of the oldest examples found to date, its significance extends beyond the mere antiquity of the mines or the export of copper ingots to civilizations outside the Iranian plateau, some of which lacked the necessary ores and others acquired the knowledge and technology for extraction much later.

What is of particular interest is the necessary exchange between major cities of the Iranian plateau for the development of related industries and their export capabilities. This interaction led to the dissemination of technology between competing cities within the region, and it is not surprising if each city contributed something unique. Metal smelting furnaces also appeared contemporaneously or with only a short interval in Tepe Yahya and Shahr-e Sukhteh.

Trade between the major cities around the central Iranian lakes was conducted via waterways. Copper ores, and later tin, extracted from one region were transported to other areas that likely had better facilities for providing the necessary fuel for the kilns or had superior technical expertise for processing. The knowledge of kilns in this region eventually led to the invention of bronze through the alloying of copper and tin. Bronze products spread across various cities of the plateau. Subsequently, significant advancements were made in iron extraction and metal plating techniques, which protected the metal from rusting.

In the sources, we see that when the Iranians invaded Egypt during the reign of Cambyses, the Egyptian pharaohs still used bronze weapons. The transition to the Iron Age could have empowered any civilization. Indeed, some researchers argue that we are still living in the Iron Age, the longest period in human technological development.

In the field of metalworking, plating techniques themselves brought about a significant leap in tool-making. In Iran, there are well-preserved steel swords from ancient times that are still in excellent condition. Meanwhile, in Europe, even into the medieval period, there were almost no swords with blades that had not rusted.

What emerged during this long period of ruptures and connections, interactions and trade, exchange of knowledge alongside competition and conflicts, was the groundwork for a shared bond that became apparent with the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire. It was not merely the result of the military dominance of one people but the outcome of a significant transformation in the legal relations among peoples throughout these stages. In fact, the Achaemenid Empire in the subsequent millennia can be seen as a product of the ‘renaissance’ of this initial seed, which gathered peoples based on a shared idea through various elements and branches

The empire was dedicated to building roads and, wherever it entered, took measures to improve water infrastructure through the construction of qanats or the digging of canals. It embraced diversity and multiplicity and did not base its urban planning on temples and altars. This was markedly different from the governance systems of Mesopotamia, which were founded on city deities, king-priests, temple power, and practices such as genocide and the destruction of conquered cities.

The specific type of social contract established here can only be understood in comparison with other regions. For example, these differences can be seen when comparing the documents of the Achaemenid conquests with the victory stele of Ashurbanipal over Elam. Or, consider the comparison with the depiction of the terracotta soldiers in the tomb of the first Emperor of China, who are all uniform and armored with minimal apparent differences, only in facial features, versus the bas-reliefs of Persepolis showing diverse peoples and races in different attire, with carvings emphasizing their unique local and ethnic signs. In these comparisons, the nature of the accepted covenant and the social contract agreed upon, which formed the basis for establishing power and its associated systems, becomes clear. It illustrates what might be a source of pride for the dominant power in each of these cultural centers.

In 647 BCE, Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian king, invaded Susa and commissioned this stele to commemorate the burning of the city and the plundering of its treasures. The inscription reads: “I destroyed the land of Elam, and sowed salt over its soil.”

The specific type of social contract established here can only be understood in comparison to other places. For example, we see these differences when comparing the records of Achaemenid conquests with the victory stele of Ashurbanipal over Elam, or in comparing the representation of the Terracotta Army in the tomb of the first Emperor of China, where all soldiers are uniform and armored with minimal facial differences, to the bas-reliefs of Persepolis, depicting hand-in-hand figures of various ethnic groups in different garments, carved with an emphasis on displaying their unique local and ethnic features.

These comparisons reveal the differences in the type of covenant accepted in each place and the social contract agreed upon by the community, which served as the foundation for the establishment of power and its related systems. They also highlight what could be a source of pride for the dominant power in each of these cultural centers.

The word “magic,” meaning related to the “Magi,” clearly illustrates how the role of the Magi, who were the ritual attendants of fire, has been enveloped in the aura of historical legends. Among the most fundamental transformations of the Neolithic era was the mastery of fire and the techniques associated with it, which dramatically revolutionized human life. Methods of controlling and mastering fire for pottery, metal smelting, glazing, glassmaking, and so on, marked a significant leap in agricultural life. This progress especially flourished on the Iranian plateau, giving rise to remarkable advancements in tool-making and trade, which in turn empowered and enriched cities.

The story of creation and the first birth

As mentioned in previous lectures, the pre-mythical (or cosmic) human lived within the heart of “timeless time,” a world that is difficult and obscure for our modern minds to even imagine. At this stage of consciousness, the concept of “birth” (the beginning of creation) was a shared archetype.

We recognize the pivotal transformation from this primordial form of consciousness to the era of myth-making by the quantification of “time.” Although primitive, deeply rooted, and enduring forms of cosmic consciousness were carried over into the era of myth-making, significant changes also occurred in human awareness. The result was the transfer of celestial functions to earthly abodes. Chronology, in particular, began with the counting of the regular cycle of the moon’s phases in the sky, which was one of the shared understandings that appeared as common myths among different peoples. These common myths then evolved into diverse branches of unique awarenesses within the founding cultures. In each of these centers, the seeds of distinct concepts were sown, and their own specific texts (historical meanings) developed.

Ancient myths and legends from each historical center provide their own narratives of the first birth, define the realm of existence, and present forms of encountering the “Other.” These myths sometimes chronicle the social life of a civilization by naming epochs associated with rulers, encapsulate collective memories of historical highs and lows in the form of stories, and ultimately offer a worldview that provides responses to fundamental questions based on their lived experiences.

Some researchers have considered Jiroft to be the lost civilization of Arete

In ancient thought, as reflected in the Torah narratives and the Mesopotamian stories, the history of the land stretches from the Mediterranean shores to North Africa and from the east to the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. In the texts of these cultures and in the explanation of the “first birth,” the concept of a singular deity emerges—a being (a word) who reveals its existence and essence through the multiplicity of a thousand names; a being whose essence is inaccessible and can only be named through its creation.

In Far Eastern culture, the primordial essence, while revealing itself, remains hidden and its multiplicity is concealed within its unity; hence, “the Dao cannot be named.” In Hindu thought, “Nāsūra” (nature) represents the first birth, and existence is born only once. In this worldview, there is no rebirth or renaissance. The world of multiplicities, or “samsara,” is seen as bubbles on the ocean of cosmic illusion.

In contrast, in Greek-Roman culture—or more precisely, Mediterranean mythology—the myth of creation is represented by “natio.” This ancient term is the root from which the words “renaissance” and “nation” are derived. There is an intriguing historical symmetry regarding these derivatives from the same root: in European thought, the concept of “nation” (in the context of renaissance) evolved with the transformation and rebirth (renaissance) of civic relations after the Christian Holy Roman Empire, and emerged from the birth of a new concept in the formation of country and nation (Etta-Nation). 25

What we find in the ancient Iranian texts known as the Bundahishn (meaning “the basis of creation”) is one of the channels that opens a pathway to Iranian myths and their hidden layers.

The Bundahishn also has its own narrative of primordial creation. Its account of human creation reflects a stage of consciousness where the distinction between body and soul is made clear within the framework of human awareness. It addresses the relationship between the human body and other living beings, such as plants and animals, as well as natural phenomena like water, earth, air, and fire. In the Yasna, which relates to the creation of the earthly body of humans, it is mentioned that the primordial cosmic body of the first human, Gayomart (equivalent to Kiumars in the Shahnameh), was as vast as the world, with equal dimensions. This depiction, which is entirely different from the human anatomical description, represents a cosmic square.

The first human in this story differs in several ways from the depiction of the first human in other intellectual systems from different centers of civilization. Here, the first human is of the fire seed, rather than the water seed. He does not have a counterpart but is unique. Additionally, with the change in life, the soul and body transform into the earthly form, rather than being created separately. In this narrative, the first human is also the first sovereign. This thought process presents the human’s role as a sovereign who comes into the world to assist Ahura Mazda in a cosmic struggle, rather than as a consequence of a fall due to sin.

The sage of Tus, Ferdowsi, brought these foundational stories into Modern Persian during a pivotal era. In the Shahnameh, we find a detailed account of the life of Kiumars and his descendants. From the seed of Kiumars comes Siamak, and then Houshang, who is the son of Siamak and the one who discovers fire. Sadeh, one of the greatest festivals among the Iranian peoples, was held in honor of Houshang and to commemorate the stage when humanity mastered fire. In Zoroastrian rituals, an institution was established for the care of fire.

In the establishment of these rites, the formation of these myths, and the celebration of the Sadeh festival, the “shared understanding” among the people of this land regarding the significance of fire is hidden. This symbolic importance should be understood in a broader sense, likely rooted in profound and tangible experiences. As mentioned earlier, we now know that one of the most fundamental transformations of the Neolithic era was the mastery of fire and the associated techniques, which fundamentally changed human life. Methods for controlling and harnessing fire, as well as techniques for constructing open and later closed kilns, raising temperatures, and maintaining heat for pottery, metal smelting, glazing, glassmaking, and so on, marked a significant leap in agricultural life. This advancement particularly flourished on the Iranian plateau, greatly enhancing tool-making and trade, and contributing to the power and wealth of cities.

The effects of such significant transformations, which impacted all aspects of life, are preserved in various layers of culture; in rituals and public beliefs, and in the myths of the inhabitants of this land, as well as in the accounts of neighboring peoples.

In ancient narratives, the prominent and fluctuating role of the Magi, who were the ritual attendants of fire, is shrouded in layers of historical legends. Greek and later European accounts attributed a range of practices to them, including magic, astrology, alchemy, and the esoteric science of material transformation. The achievement of new metal alloys, which provided materials with enhanced strength, malleability, and suitable combinatory properties for crafting various tools, was no less remarkable than magic.

We mentioned that Houshang was renowned for his mastery of fire. Scholars argue that the gradual development of fire control required the establishment of permanent dwellings, due to the necessity of furnaces and kilns, which were difficult to move and reconstruct repeatedly. Interestingly, the construction of fine houses is also attributed to Houshang. His name in Avestan carries this meaning: one who builds a good home.

In the ancient roots of this culture, we can find more examples of the importance of settled life, house-building, and city founding, which have become common narratives among its people, reflecting the reciprocal relationship between lived experience, skills, culture, and beliefs. For instance, one of the six Amesha Spentas in ancient Persian is named Kshathra Vairya or Shahrivar, which denotes a model of good kingship. The first part of his name is the root from which the words “brick” and “city” are derived. The ideal ruler is described as one who lays good bricks or, metaphorically, as the founder of a good city. Today, the term “Shahrivar” (city builder) continues to reflect the special significance of city-building, settling, and constructing good homes in this culture. 26

Similarly, there are significant references in myths and texts from various sources about prosperous cities involved in mining, industry, and trade of minerals. These references, which might be better understood with detailed archaeological work in the future, include mentions of the Sumerian city of Aratta. According to Sumerian texts, Aratta was located to the east, accessible via Anshan (Khuzestan) and beyond high mountains and seas (possibly one of the central Iranian seas).

In various Sumerian texts, Aratta is described as a desirable, wealthy, and prosperous city with skilled artisans and substantial treasures of lapis lazuli, agate, and metals. The city is particularly noted for its colorful walls and its lapis lazuli towers. In addition to these scattered references, there is a detailed account where the Sumerian ruler Ur seeks to import building materials, precious stones, and metals from Aratta for the construction of a temple in Uruk. To this end, emissaries are sent to negotiate with the city. Ultimately, Aratta is conquered by the Sumerians.

The name of the city, referred to as Aratta in Sumerian and later Akkadian sources, shares roots with the second part of the name Khuniratha (Khunirsa) in Iranian mythology. Aratta derives from the root rathe meaning “wheel,” while Khuniratha translates to “wheel of the sun.” In Iranian mythology, Khunirsa is one of the seven realms of the world, with Iranshahr located within it.

Similarly, in the Bundahishn, the description of the ideal city Kang-Diz closely resembles the city of Aratta in Sumerian sources. It is depicted as wealthy and industrialized, with “seven walls: golden, silver, steel, brass, iron, crystal, and lapis lazuli.” 27

With further research, it may be possible to gain a better interpretation of these stories, which offer scattered images of prosperous ancient cities that were envied in their time. Over the centuries, these cities have evolved, merged, and continued to exist at various levels of cultural and historical significance.

In the Bundahishn and Minoyi Khirad, it is mentioned that there is a tree named Bas-Tukhma, which grows in the middle of the vast sea Farakard. This tree holds the seeds of all plants. It is created on top of nine mountains, with the “pierced mountain” from which nine thousand and nine hundred streams flow, and from which the waters of the seven countries’ seas spring. This tree is known to drive away sorrow and is the source of all medicines.

And the Simurgh—Sennay the healer—makes its nest in this tree. When it rises from the tree, a thousand branches will sprout from it, and when it sits upon it, a thousand branches will break, scattering the seeds of the tree, from which new plants will grow. The roots of this tree are protected in the water by paired fish that turn away from the onslaught of evil.

The revelation of the world within the term Bundahishn reminds us that the roots of the tree of awareness lie deep in the darkness, even though its birth occurred in timeless light. The tree stands firm on its own roots. In Iranian thought, Ravan (soul or spirit) is a concept that is both flowing and eternal, and in the Bundahishn, it is compared to the trembling of the countless leaves of a tree (the Tree of Life). Similarly, in the shared linguistic family of ancient Germanic languages, the term Gyst also conveys the idea of trembling.

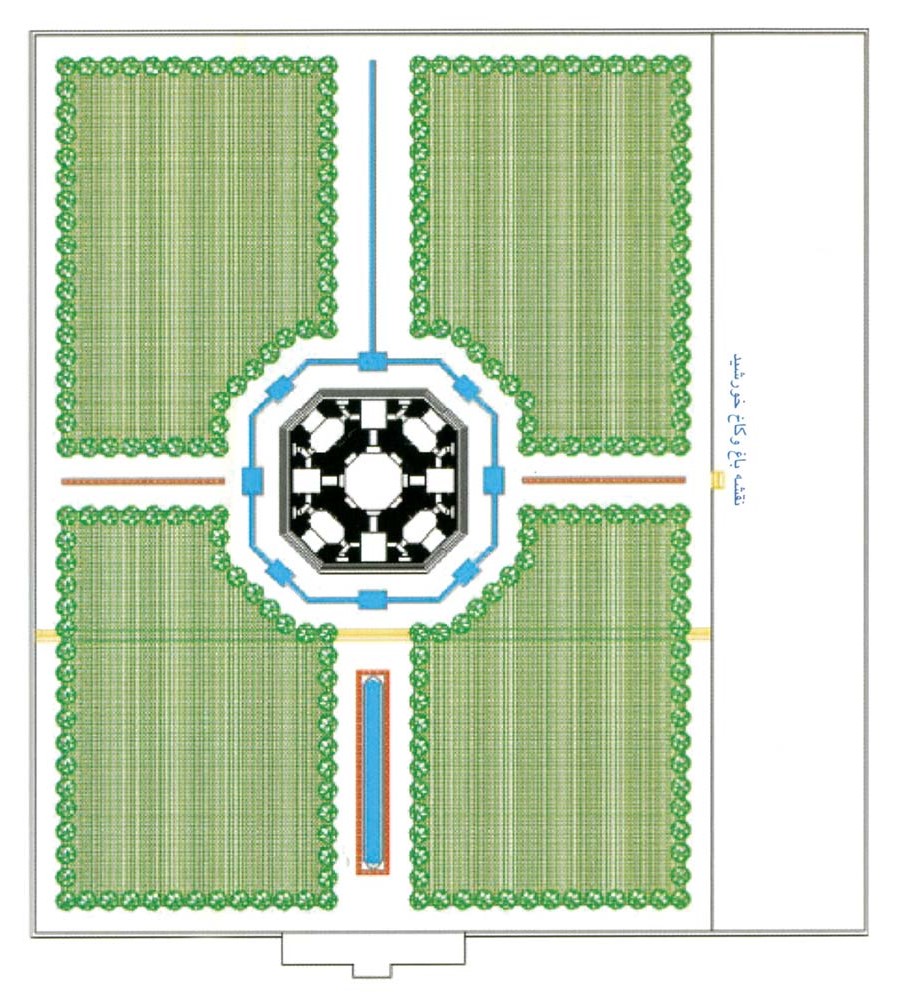

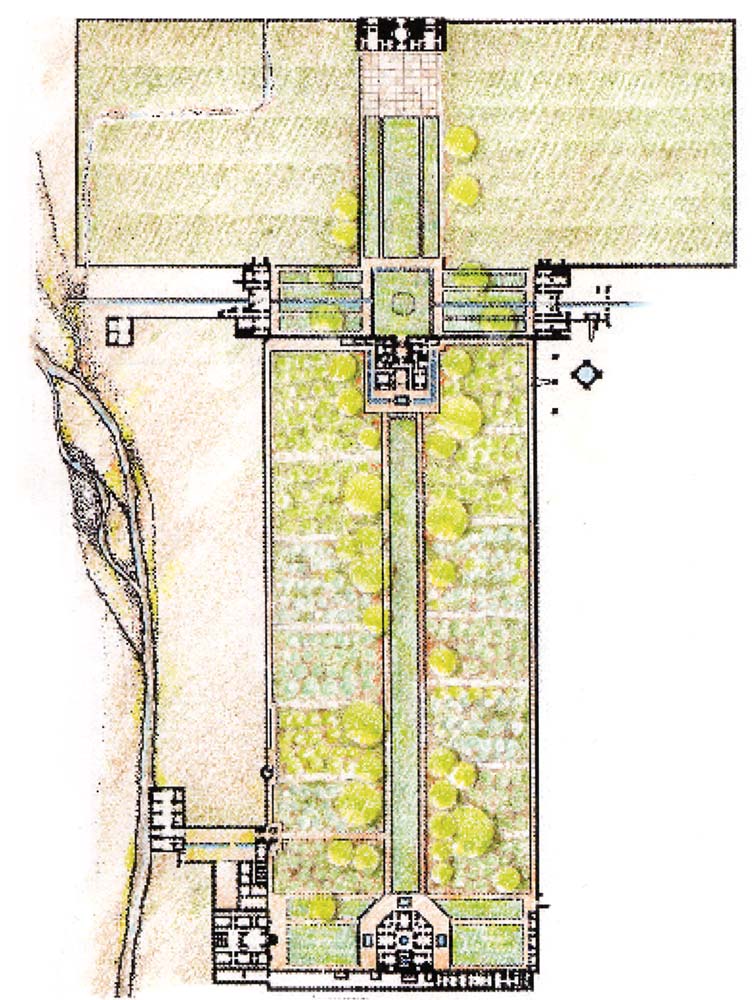

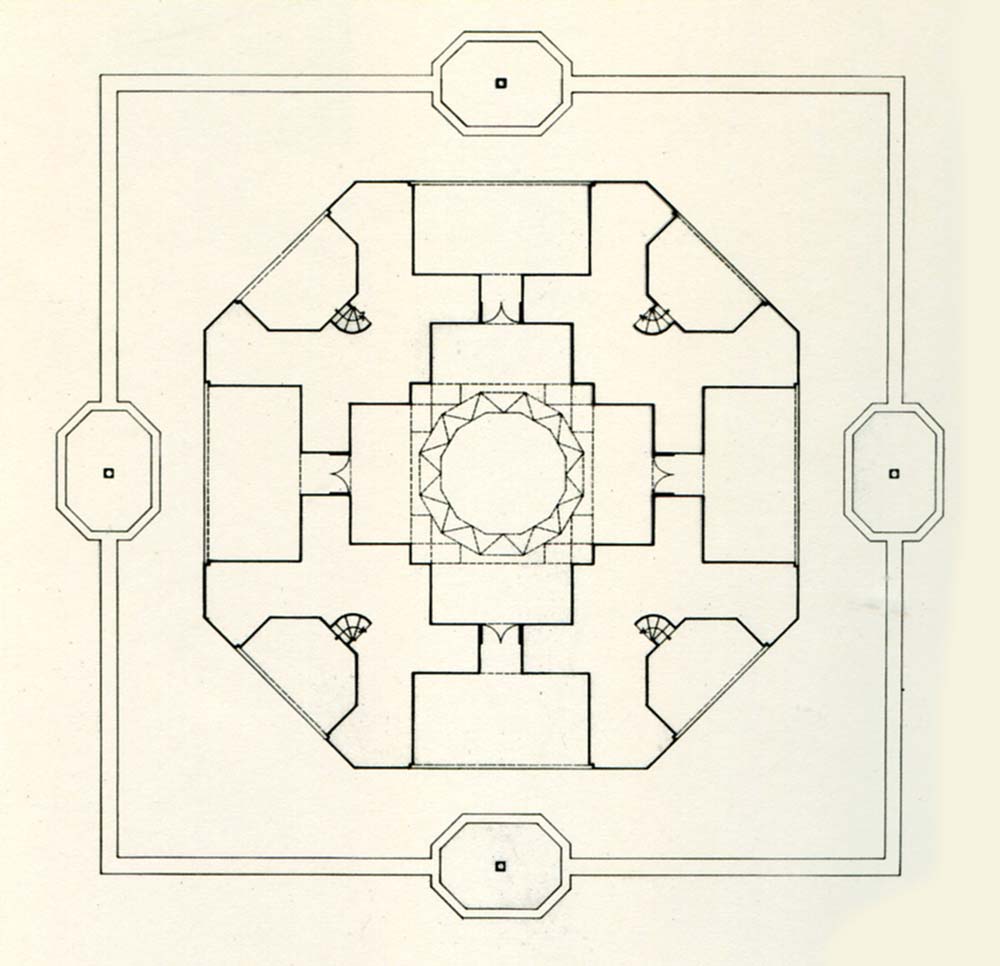

On the other hand, the symbol of the cross, or Khyro as it is known in Mithraic tradition, represents the initial conceptualization of a measurable relationship with the world. This becomes possible only when humans settle in a place and establish a central point or origin. This symbol of the cross, or Dār (note the word Dār — tree — also implies Dharma), which stands like the robust Tree of Life, forms the basis of “designing” in Iranian thought; from carpets to gardens and to cities.

How can a civilization be considered the founder of a culture and thought system unless it establishes foundational ideas that create shared patterns for calendaring, organizing social life, designing villages and cities, patterns, musical frameworks, and literary themes?

The foundations of the civilization established here were not based on the idea of colossal shamanic deities but were grounded in the sanctity of the world. The culture’s emphasis on settlement, expanding habitation into pristine areas, irrigating dry lands, and condemning violence reflects a maternal concept of valuing both “life” and the “world.” This contrasts with the foundational ideas of some other civilizations, as it has a feminine core, encapsulated in the concept of Sennay or Simurgh. The extension of the ritual meal of Yasna or Yasna across a vast domain signifies the honoring of this new awareness and the reverence for this new consciousness.

Footnotes:

- For further reading, see Standich, Tan (2014).

- For further reading, see Diamond, Jared (2017).

- For further study, refer to the archaeological research of Russian scholar Alexander Marakovich Blintsky.

- Standich, Tan (2014).

- Standich, Tan (2014).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Diamond, Jared (2017).

- It should be noted that the most significant and extensive research has been focused on European history, particularly Greece, and the tracing of anything leading to this civilization. Research in Western Asia has largely been aimed at following the trail leading to Greece. Although these studies are quite useful in the absence of other scientific work, they mainly serve to illuminate missing points in European history or the relationship between Europeans and others.

- Standich, Tan (2014).

- For further reading, see Diamond, Jared (2017).

- Jacques Cauvin, Neolithic archaeologist.

- Stegast, Mary (2011).

- Several Greek and Roman writers, including Xanthos, Pliny, Eudoxus, and Plutarch, have cited an approximate historical life of Zoroaster between 6500 and 6200 BCE.

- According to Bruce Lincoln’s research, the myth of the theft of cattle in Indo-European mythology is very ancient. In Vedic hymns, the heroic task of the warrior is indeed the theft of cattle. Lincoln has reconstructed this early Indo-European myth using the mythological traditions of various Indo-European peoples, such as the Greeks, Germans, Celts, Romans, and even Hindus. In this myth, a three-headed monster seizes the hero’s cattle, which are then recovered with the help of a warrior god (Vedic = Indra; Celtic and Germanic = Wodan). The origins of these acts date back to the eighth millennium and the presence of domesticated cattle in Neolithic pre-pottery settlements, including the Iranian plateau. Zoroastrian teachings diverge from this common tradition of its time, describing such beings as marauders who destroy human society (Gathas 32:12).

- Vendidad, Fargard 3, Section 1.

- Interestingly, in Greek sources, the historical antiquity of the figure of Zoroaster, as reported by some historians quoting the Magi, aligns almost perfectly with the creation of his spiritual essence in Zoroastrian belief, which, according to their traditions, occurred millennia before Zoroaster’s birth. This precedence of his “soul” over his birth can today be seen as a metaphor for the formation of the seeds of a new consciousness whose achievements were later compactly presented in texts that emerged in this region, including the Gathas.

- The aridification of the Iranian plateau occurred from the ninth to the fourth millennium BCE, peaking between the eighth and fifth millennium BCE. For further reading, see Jahanshah Darvishi (2004).

- From 550 to 331 BCE, the Iranian Empire expanded from the Indus River to the Nile. The development of qanat technology is associated with this period. Qanats were constructed in the western Iranian plateau from Mesopotamia to parts of the Mediterranean coast and sections of Egypt. Similarly, in the east, qanats were built in Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Chinese Turkestan. They acquired different names in each region: Kariz in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Kanarjing in China, Falaj in the Arabian Peninsula, and Foggara in North Africa. For further reading, see Mays, Larry W. (Ed.). Ancient Water Technologies (2010). Springer, Dordrecht/ Heidelberg/ London/ New York.

- Jahanshah Darvishi (2004).

- In addition to archaeological evidence, the Darius inscription also mentions Sogdiana as the source of lapis lazuli, of which Badakhshan was a part.

- Jahanshah Darvishi (2004).

- For further reading, refer to: Dadvar, Abolghasem; Mossa Bahadori, Nasrat al-Muluk. “Review of Theories on the Origin of Luristan Bronzes.” Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Isfahan. Spring 2007, Issue 48.

- It should be noted that the birth of Christ is not understood as a rebirth. In Christian theology, the three hypostases (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) are eternal and pre-creation, and the concept of Jesus Christ is understood in relation to the incarnation of God.

- “Khshtar” derives from the root “Khshi” and means to build, construct, or develop. From this root, words like “khesht” (brick), “shahr” (city), “shahriyar” (sovereign), and similar terms are derived.

- Jahanshah Darvishi (2004).

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.