An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

The rapid pace of changes in the modern world, which we experience within our lifetimes, brings to mind the assumption that in any short span of time, the world can fundamentally transform. This is especially true in our current societal conditions, where the desire for modernization swiftly erases any trace of recent urban memories and replaces them with newer and more “up-to-date” forms. In such circumstances, history might seem to the public like an interesting set of general knowledge that doesn’t necessarily relate to our present-day lives. For some, it represents a kind of pathological pride in a glorious past, while for others, it’s a heavy weight that hinders our ability to modernize quickly.

It is important to note that behind this façade of constant renewal, one of the essential sources that helps us understand our current tendencies and beliefs is the recognition of resilient natures and structures. These elements can reinvent themselves in new forms and continue their existence. However, for many, any discussion about the persistence of fundamental and underlying structures of human thought—from ancient times to the present—is preemptively dismissed and labeled with essentialist critiques, especially using tools influenced by postmodern ideas. Yet, understanding human society historically in the modern era relies on uncovering and recognizing these contexts, which have been woven from ancient times to the present. These contexts manifest as functions, archetypes, or the core tenets of civilizations’ thoughts, woven with their ancestral threads. Sometimes they extend ancient patterns with new strands, or during pivotal moments, they undergo transformations, starting a new pattern within the old context. Change and transformation, particularly in Iranian culture, as will be explained, are not only possible but vital. However, any fundamental change in the deeply layered and profound realms of experience and thought occurs through the interaction of new insights with ancient holdings, and this process happens gradually.

With this introduction, we move on to a new lecture; humanity is inherently social and, as far as we know, has lived in groups since the beginning. Within these early groups, and through a very long process influenced by environmental exigencies and opportunities, various forms of social contracts, ethical agreements, ritual beliefs, and power structures emerged, forming different cultural nuclei.

Nomadism in pursuit of hunting, or later in search of fodder for domesticated animals, and in the agricultural era, the stages of planting, cultivating, and harvesting, each required planning and group cooperation. Organizing these activities necessitated various methods of experience transfer, coordination, and the establishment of collective rules. From these processes, early communities developed in different dimensions. The gradual establishment of power structures resulted from long periods of conflict and experimentation with ways to organize collective affairs. Typically, a mechanism was found whereby the group would delegate power to an individual, and a person would rise to leadership, ostensibly to serve the interests of the community.

In early human groups, the most fundamental social bond was the instinctual relationship between mother and child, which was the only clear blood relation within primitive tribes. The role of the father was not recognized, and sexual relations occurred among the members of the group. Despite historical changes, such structures still exist in some regions of Africa and among certain tribes in Uganda and Kenya, where their social systems are based on ancient ties and beliefs. In these societies, the care of children is exclusively the responsibility of the mothers. Subsequently, kinship among the children of the same mother began to expand. Traces of this ancient bond persist in later periods among some communities or tribes where lineage, religion, or ethnic affiliation is inherited exclusively from the mother. Additionally, remnants of this family relationship, in which a brother naturally recognizes and can support his sister, are seen in some tribes with matrilineal customs and rights.

The addition of the father’s role and the exclusivity of sexual relations within the new family structure were related to the emerging needs for longer education and support for children. Thus, following this initial nucleus, additional family members gradually joined and took on roles.

Larger communities, in the form of “clans,” responded to the need for cooperation in gathering food and ensuring security. The consolidation of clans into a “tribe,” around a social contract, provided the group with greater power, order, and cohesion. Entering into tribal alliances marked a significant shift in human awareness. Tribes, unlike larger alliances, were primarily characterized by a lack of dependence on land or country 1, and ownership often extended to the tribe’s members, including women and children. The tribal individual recognized the tribe’s god and its members. Neighboring tribes were usually either at peace or at war with each other.

Since the power of each tribe depended on factors such as population and procreation within its structures, the killing of a tribe member by another or an attack on one’s honor could lead to endless blood feuds. Wars between tribes could be perpetual. The mechanisms for ending such conflicts involved either the complete dominance of one tribe over others or the creation of new family ties through marriages between individuals of different tribes. Ultimately, through the formation of councils of tribal leaders, a temporary truce and peace were usually established.

The names of family members that are common across languages originally denote the roles of these individuals in ancient Persian. For example, in the word “پدر” (pedar = father), “پی” (pi) comes from the root meaning to support, with the suffix “تر” (tar) or “تره” (tareh) added to signify familial relation. Similarly, the transformation of the word “برادر” (barādar = brother) in English into two different words, “brother” and “porter,” illustrates how one carries an abstract meaning while the other directly signifies the ancient meaning of the word. Likewise, in the word “دختر” (doxtar = daughter), “دوغ” (doogh) or “دويي” (dowwi) means milk, referring to her role in producing dairy products. These words, along with the advancements of animal husbandry and agriculture, spread from East to West across vast territories among various peoples.

If awareness, consciously guided, continues to evolve in certain regions, larger societies have emerged that are born out of the alliance of tribes into a “tribe” or “people”. National consciousness is a result of such ruptures that transform all aspects of people’s lives; their perception of identity, collective rituals, arts, power structures, understanding of interests, and how to defend them, all influenced by this kind of awareness. For example, a transformation of awareness among ten tribes of people residing in Egypt led to an alliance around a covenant that transformed them into the “Children of Israel”. In this new awareness, the Children of Israel recognized themselves as a chosen people, constructing all their interactions and relations with neighboring tribes and peoples differently.

Around this enduring awareness, a power structure emerged over a long history that prevented these people from assimilating into the hearts of other tribes and lands, leading to the segregation of worship places and synagogues, the creation of ghettos, and the establishment of their own legal judiciary system and the scheduling of specific holidays and days off wherever they went. 2

The process of transformations, in some cases and under significantly complex factors, may culminate in larger social contracts and the birth of a “nation”. It should be noted that each stage of expanding the scope of these contracts does not negate smaller bonds that preceded it. Just as the most basic family ties can remain powerful and meaningful within a nation, so too a national covenant does not necessarily negate its subgroups of tribes and clans. A national covenant represents a new form of awareness that binds a larger and more diverse population together beyond familial and racial ties, creating a broader meaning of public interests, participation, and cooperation in safeguarding these interests.

In this context, a nation is built upon a socio-cultural infrastructure and framework of a common language in its broadest sense, reinforcing artistic, linguistic, and cultural commonalities. Similarly, within this covenant, people’s connection to their land takes on a new form, embodying the concept of “country”. The necessary precondition for this journey and the expansion of public covenants has been profound and fundamental shifts in collective consciousness among peoples, which have not occurred easily or universally, and when they do, they reshape worldviews, beliefs, narrative structures, arts, and approaches to confronting social crises.

As we observe in today’s global interactions and conflicts, under modern constructs such as “state” and “nation,” these structures continue to be crucial and defining factors in social systems. Tribal social bonds remain dominant in many African, Arab, and Turkish countries, while the foundation of power in some modern nations is built upon ethnic, racial, and kinship structures. Contemporary Turkey and Israel, for instance, define themselves through various forms of these ethnic and racial bonds. The Balkan crises and extensive ethnic cleansing in recent centuries have starkly highlighted the persistence and power of ethnic bonds among the peoples of these regions in their most violent forms.

These examples and numerous others illustrate that political boundaries established post-World War I and II and under agreements like Sykes-Picot, while based on international legal frameworks, do not necessarily reflect spiritual, cultural, and social bonds, nor do they indicate a shared understanding and acceptance of power dynamics in these societies.

Social structures vary everywhere and persist beneath the uniformity of modern titles. For example, the political power structure in Lebanon, despite the establishment of parliament, free general elections, and the entry of educated European generations into politics, still revolves around tribal leaders and remains hereditary from fathers to sons.

In the modern era, every group of people living under the banner of an independent “state” has been designated with the term “nation” alongside tolerance. However, simply applying these labels cannot create cohesive nations unless these people undergo a profound transformation in their social consciousness, leading them to establish a “national covenant” or foster a pervasive national culture among themselves. Otherwise, we observe so-called “nations” with precarious structures that collapse at the slightest external provocation or internal discord. These nations often descend into endless wars among tribes and factions, which national interests alone cannot compel to unify and transcend ethnic, tribal, racial, or religious differences.

About the climate

In references to the types of awareness during cosmic and mythological eras of humanity, we have focused more on ancient patterns and common myths of humans migrating and spreading across the expanse of the Earth. These common patterns evolve through stages of diversification. The disposition of human groups is influenced by the climatic characteristics of the regions in which they flourished, laying the foundation upon which subsequent cultures and civilizations are established.

The use of the term “سرشت” (serešat) here should not be understood as synonymous with “ذات” (zaat), which implies an immutable and intrinsic nature. “سرشت” in its literal sense refers to a woven fabric of human conditions, interactions, and experiential differences that intertwine over millennia. The resilience and resistance of ethnic dispositions against rapid and episodic changes stem from the antiquity and depth of both explicit and implicit cultural layers. The history of culture, in essence, is a history of twists and turns, knots and connections, or the continuity and discontinuity of threads of fragmented awareness drawn from the depths of history to the present day. Contrary to all ideologies that advocate a return to origins promising a pristine cultural revival, it should be noted that rejecting strands that have played a supportive role in the fabric of thought makes culture more vulnerable. 3

The importance of climate lies primarily in its role as the foundation upon which human beings depend to meet their basic survival needs. Beyond that, it shapes the initial coordinates of one’s soul based on the climate and natural factors such as mountains, rivers, seas, and the elements experienced in the sky and on the earth.

Several distinct types of climates can be recognized, each influencing human communities that settle in regions by chance or choice. This diversity leads to differences in their awareness, physical well-being, and psychological states, without necessarily diminishing the intrinsic worth and dignity of humanity.

In lands that we might deem “unyielding,” the violence of nature becomes the central challenge of human endeavor for survival and existence in the literal sense. These lands encompass a wide range of regions, from extremely cold habitats like those of the Eskimos, to very hot and arid areas such as the vast deserts of Africa, or dense and heavily rainy forests. We experience that in such geographies, the possibility of forming large civilizations has not been readily achievable. The linguistic limitations of the peoples inhabiting these regions illustrate the constraints on cultural development in these habitats.

Comparing the names relative to languages with their environment demonstrates to what extent climatic conditions have influenced the development of human sensitivities. For instance, among the residents of Siberia and the Eskimos, there are more than fifty names for the color blue, while many other colors may not have designated names.

In contrast, there are other regions on Earth characterized as “effortless” in terms of temperature and soil fertility. The abundance of natural blessings and food reduces the necessity for intense cultivation efforts, making humans largely independent of animal husbandry to a considerable extent. Additionally, in these lands, the need for sophisticated architectural techniques for shelter construction and the challenge of producing textiles for clothing are significantly reduced. Examples of such habitats include the islands of Southeast Asia, the Caribbean islands, Polynesian islands, and the southern part of the Indian subcontinent.

In these environments, specific types of social and ethical systems have typically evolved. The lack of vital need for labor does not necessitate a structured definition of family units or children’s attachment to them. Moreover, the fertile nature of some of these regions may foster diseases specific to them, which can decrease population growth, and in some islands, various forms of infertility may occur. This necessitates a different definition of family and the relationship between men and women. Usually, in such societies, as seen, for example, in the Caribbean islands, ethics tend more towards supporting diverse and varied sexual relationships that may increase fertility chances, yet there is no need for patriarchal substructures. In some of these areas, because war over vital resources is meaningless, games and various ceremonies serve as venues for practicing agility or showcasing communal strength. As historical fate shows, effortless regions, like unyielding ones, have not been the birthplaces of civilizations and great cultures.

Arts are influenced by human biological experiences and the nature of human interaction with the environment. This aspect not only manifests broadly in the art of each culture and civilization but also in contemporary works where examples of such connections can be found in the works of every artist.

Mark Rothko’s works represent a kind of portrayal of the human spirit in a state of historical detachment from a specific land. His mature paintings depict the childhood memories of migration and constant displacement across the world. The large, misty windows and steam-filled trains that constantly moved his family during his childhood are positioned as sanctuaries and icons of mental tranquility. These themes are repeatedly reproduced and extended throughout his lifetime in the form of saturated color fields.

The third type are lands we can call “effort-permitting”. In these regions, human life necessitates effort, yet the nature there accommodates and rewards such effort. Struggling against nature to tame the environment and competing with others over limited resources fosters a logic that underpins further creativity. Humans cultivate crops, construct tools, and discover natural laws to understand their surroundings, becoming legislators of their social environment. These achievements, facilitated by the opportunities granted by the climate, are passed down from generation to generation and evolve. The remarkable transitions from the Stone Age to the Metal Age occurred predominantly in these biologically diverse lands, which have harbored the largest populations of human civilization.

In some of these regions, nature exhibits an “unbalanced” temperament. While efforts can be made to foster culture and civilization there, the constant threat of storms, tsunamis, and earthquakes looms, constantly disrupting equilibrium. Natural disasters occur everywhere, but the difference lies in the frequency and severity of these destructive events in these lands. Japan is a prominent example of a civilization that has thrived in such a climate. This aspect can be recognized in various aspects of Japanese culture, ethics, and aesthetics, where this lack of balance has become an integral part of their way of life.

In the Japanese aesthetic tradition, asymmetry, irregularity, and imperfection are acknowledged as recognized forms of beauty. Japanese culture in aesthetics, poetry, and music doesn’t seek to add, but rather subtracts and refines, giving rise to a unique form of beauty that is a product of a climate that permits effort but denies excess.

Similarly, parts of these effort-demanding lands, alongside seas or in the vicinity of active volcanoes, sudden heavy storms, and terrifying lightning strikes, have given rise to the core of civilizations where the essence of fate and tragedy is prevalent. Life and death on the island of Crete in Greece and on the Mediterranean peninsulas have been shaped by such occurrences.

Or the devastating cyclical storms that sweep across the continent of America periodically, with immense force beyond human control, completely devastate the lives of its people.

Paul Gauguin’s works are a fascinating example of the juxtaposition of two different life experiences. His presence in Tahiti and his artistic choices can be seen as a reaction to the social environment of his time and the dominance of Victorian ethics in that historical period. Therefore, these works are meaningful within the historical context to which he belonged. Confronting the diverse environment of the Pacific Islands and their people, Gauguin paints the sky with different colors. His use of contrasting colors for everything indicates that he found another world here, with different ethics, customs, and belief systems of its own.

In contrast, some regions categorized as resilient exhibit relative stability in natural behavior. Among these, resilient and stable lands also feature diverse climates. In such areas, richness of meaning emerges, fostering opportunities for challenge and growth. For instance, significant differences between Roman and Greek civilizations in their stable, diverse climates highlight the potential for various experiences and the interaction of ideas, facilitating the development of medical or culinary schools. Moreover, in the expansive lands of Rome, accumulation of wealth and stability provided a foundation for the establishment of armies, signifying a logistical apparatus capable of managing military forces and ensuring their support across vast territories. In other words, in the example of Rome, the climatic environment supports its civilization by allowing it to flourish in its own densely interconnected manner. Similarly, this principle applies to Iranian civilization, albeit with fundamental differences rooted in the cultural distinctions between these two spheres.

The climate in which Iranian civilization thrived was resilient, stable, diverse, and, moreover, four-seasoned. Although natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes have occurred frequently, the interval between these events over a vast expanse can be considered relatively stable. Additionally, in the realm where Iranian culture took shape, the experience of the four seasons entailed a complete transformation of nature four times a year in most regions. For instance, in the case of Rome, the vast expanse of the territory did not necessarily mean that the four seasons were experienced uniformly across its entire domain; the Mediterranean region was nearly single-season, and in Northern Europe, the harsh winters of past millennia almost exclusively dominated.

In the Iranian climate, alongside limited rain-soaked areas like the Mazandaran plain, there were vast lands where irrigation was discretionary; meaning water was not readily available but could be obtained through effort and creativity. The most flourishing areas of the Iranian plateau were typically those where controlling and harnessing water required considerable effort and toil.

The topic of climate is not confined to these broad and general categories alone. Each region’s unique natural characteristics have sometimes caught the attention of thinkers. For instance, Hegel points out how nature in “non-structural” lands influences the human spirit and their understanding of the origin’s meaning. Living in regions where there are endless sand dunes or snowy hills that reshape with every wind or rainfall is different from the experience of people who rely on a stable natural environment, one that appears eternal, immutable, and enduring, evoking the idea of a center in their minds, such as a mountain from which waters spring or an ever-flowing river.

Moreover, the geographical position of a land can influence how much its people interact with neighboring cultures. The distinct cultural differences between the inhabitants of islands or inaccessible regions and those living along trade routes stem from this factor.

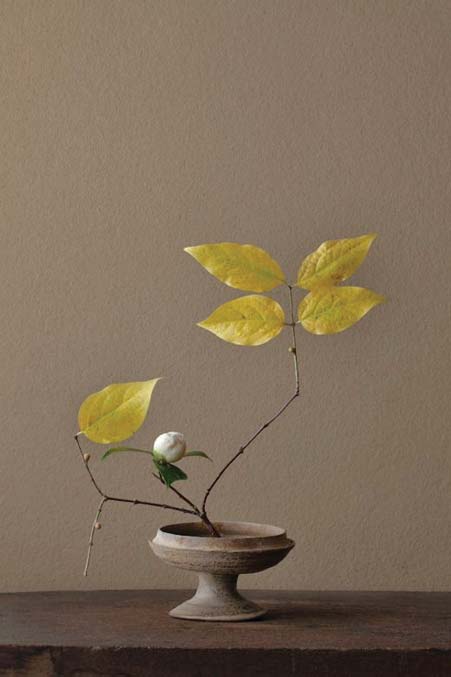

The Japanese aesthetic system integrates the concept of imbalance into its way of life as an inseparable part. Here, asymmetry, imperfection, and flaws are recognized and appreciated as elements of beauty. In Japanese culture, particularly in aesthetics, poetry, and music, instead of adding, there is a process of reduction and refinement, creating a unique form of beauty that results from a climate that is laborable but not consistent. One of the techniques in ikebana (Japanese flower arranging) is creating harmony by combining dried plants with fresh blossoms.

In the kintsugi technique, broken pottery pieces are rejoined using a special lacquer mixed with powdered gold. The resulting product symbolizes the search for beauty in destruction and reminds us of the value of brokenness. Furthermore, these aesthetic traditions reflect the influence of Confucian ethics, where the elderly are revered within its hierarchical structure.

Similarly, the juxtaposition of diverse climates in certain regions can influence various layers of the civilization that emerges in such environments. In India, Vedic art and Hindu philosophy flourished in a land situated between the climates requiring minimal effort in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent and the effort-demanding regions in the north, embodying characteristics of both these living conditions. This quality of “being on the border” and “being tangent to” two types of worldviews can be observed in various cultural aspects that have developed in this climate. It is a civilization that has reached a pinnacle of logic and rational action on one hand, and on the other, nurtures a passivity that is equally powerful. The soul that has grown in this environment exists simultaneously within both of these worlds.

After these explanations, the difference between “nature” and “essence” becomes more evident. Although nature is ancient, it is not eternal and unchanging; it is in a state of becoming, but its changes are very gradual and always in relation to its past. The climatic influences on the nature and culture of a people span several hundred thousand years. Over millennia, climates themselves have gradually changed. Human populations have moved through migration or conquest. All these factors make the relationship between climate and collective nature complex and not straightforward.

Among the civilizations that emerged in adaptable regions, the concept of foundation and establishment reached a higher level of complexity in five core domains, leading to a profound understanding. Over an extended period in history, these civilizations achieved durability and permanence. Each of these civilizations has manifested unique facets of the human spirit, forging distinct existential relationships with being that are exemplified most profoundly through their arts.

These five major centers are:

• The ancient world in the Mesopotamian region and along the Nile River.

• The Indian subcontinent.

• The Far Eastern world centered on China.

• The Greco-Roman world.

• The Iranian world.

One of the most distinguishing features of the five cultural centers mentioned is the development of language and its poetic essence, resulting in the establishment of meaningful vocabulary and the formulation of narrative frameworks within each of these centers. The emergence of a historical language signifies a departure from the natural evolution of language, occurring where the amalgamation of people’s lived experiences in a common climate forms shared myths and narratives. These gradually evolve into comprehensive collective narratives that can address humanity’s questions about its essence, time, and existence. When these answers are crystallized in written texts, the dawn of literary magic in that language arrives.

From this perspective, within these five foundational centers, five profound written texts have emerged, each with significant differences that have not been equaled elsewhere. These five repositories of written texts are:

- The Ancient Covenant, whose stories relate to the displacement and dispersion of peoples within the cultural center.

- The Upanishads, in the literature of wisdom and dialogue, and the teachings of Buddha in the northern Indian subcontinent.

- Taoist texts and the speeches of Confucius in China.

- Homer’s Iliad in Greece, and Virgil’s Aeneid in the Roman-Latin tradition.

- The epic texts of Iran from the Avesta collection (Gathas, Yashts, Vendidad, etc.), continuing into its poetic compositions.

In this context, we do not delve into civilizations such as the Incas and other peoples who lived in America. While these civilizations developed concepts of power, legislation, and social organization, the persistence of shamanic consciousness weakened and made them vulnerable. The underlying illusion in shamanic beliefs, which posed a barrier to experiencing rupture and distancing between humans and existence, rendered these cultures sterile in historical formation. Ultimately, these great civilizations in the 16th century, when confronted with the external world, not only failed to withstand the arms and violent behavior of invaders but also could not withstand the new awareness, causing internal disintegration and eventual extinction.

Ancient cultural center

The vast lands stretching from Mesopotamia to Africa in Sudan, Eritrea, and along the Nile have been the cradle of ancient civilization and culture. This vast expanse extends from the southern and western shores of the Red Sea (Yemen) to the region of Eritrea (Abyssinia) in East Africa, reaching to the Nile Delta in North Africa (Egypt) and the eastern Mediterranean coast (Jordan and Palestine), and concludes in the east at the Euphrates. This cultural hub had a presence in the western part of Iran and its long history of interaction with Iran has positioned it as one of the sources and texts of Iranian culture.

The environmental conditions of this vast region facilitated the emergence of the first civilizations in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Babylon, and Sumer, as well as one of humanity’s greatest civilizations centered on Egypt. 4 The initial social structures of these societies were tribal. Villages in weaker areas either came under the influence of more powerful centers, merged through warfare, or fragmented apart. The pantheon of gods was diverse, where each natural phenomenon, individual, or concept had its own deity with human-like attributes.

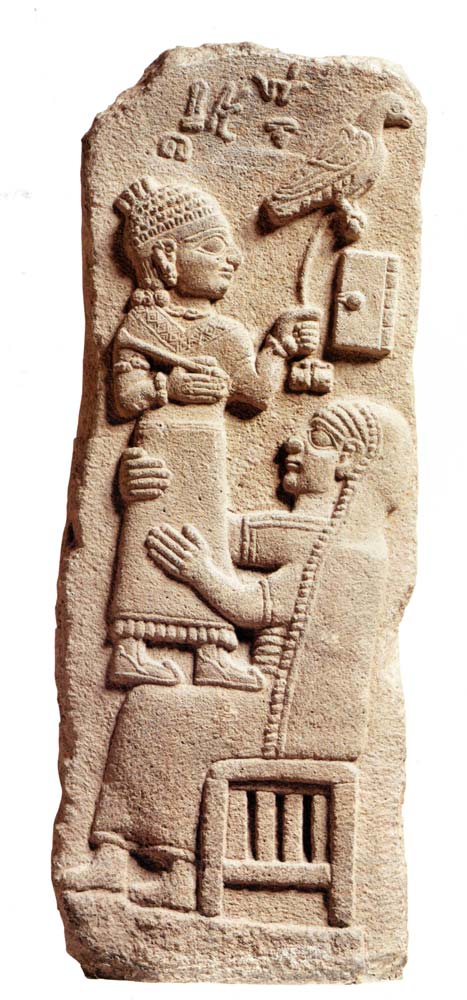

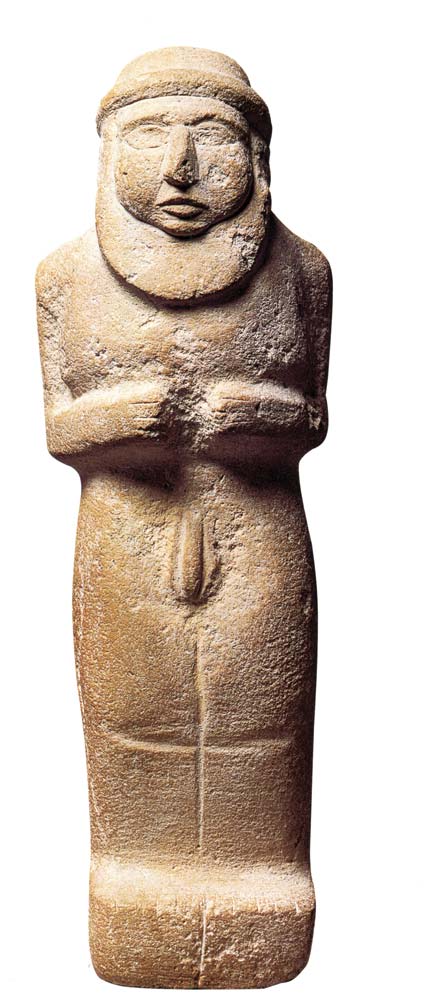

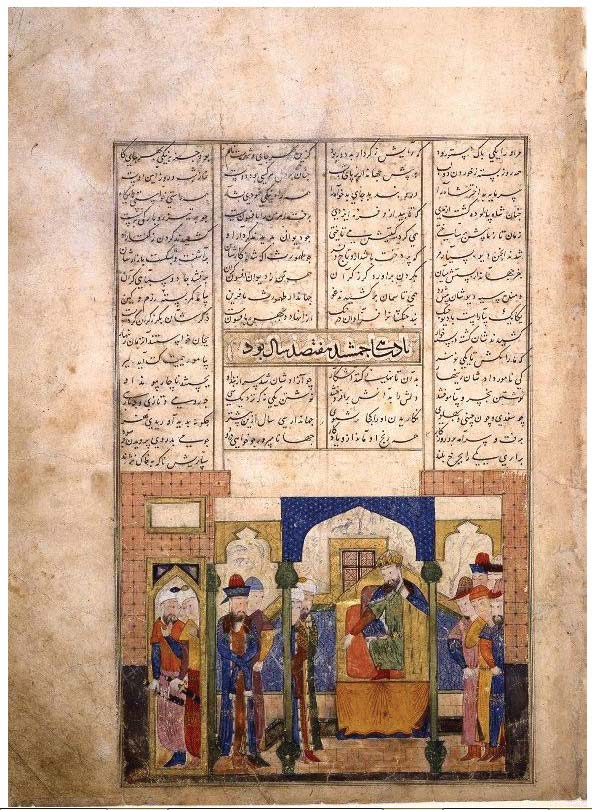

Thus, each city had its own assembly of gods who acted as protectors, and dominance of one city over another implied the superiority of that city’s gods. Over time, these gods merged and formed more cohesive pantheons across neighboring regions. The power structure was dominated by a system of rulership intertwined with priesthood, holding divine authority and acting as intermediaries between gods and ordinary people. Their statues depict them in direct communication with the gods.

This fusion and amalgamation in the land of Egypt led to the formation of two kingdoms: Lower Egypt in the Nile Delta region, and Upper Egypt in the Nile Valley. The greatness of Egypt reached its zenith when these two regions unified. In the Egyptian conception, the Nile was a vital lifeline whose origin was unknown, flowing from an unreachable place beyond several mighty cataracts in impassable regions, towards the desert and into the sea. As mentioned earlier, the core of this civilization was influenced by the contrast between the arid climate of the region and the life-giving qualities that the Nile extended along its banks. The experience of life in such a dry climate, periodically rejuvenated by the flooding of the Nile, profoundly shaped the Egyptian understanding of the possibilities and laws governing the universe.

It was in this context that a culture developed, with the idea of the return of the soul to the dead body as one of its fundamental principles. Hence, the practice of mummification, a method of preserving the body to facilitate the return of the soul, became prevalent, and tombs gained extraordinary importance. Arts, crafts, and sciences flourished in connection with and in service to these fundamental beliefs. Egyptian cities all took shape around and in proximity to these tombs. In the culture of this region, the most significant motivations stemmed from a fear of separation and the dread of the chain of life being broken, beliefs continually reaffirmed by the experiences of the people living in this climate.

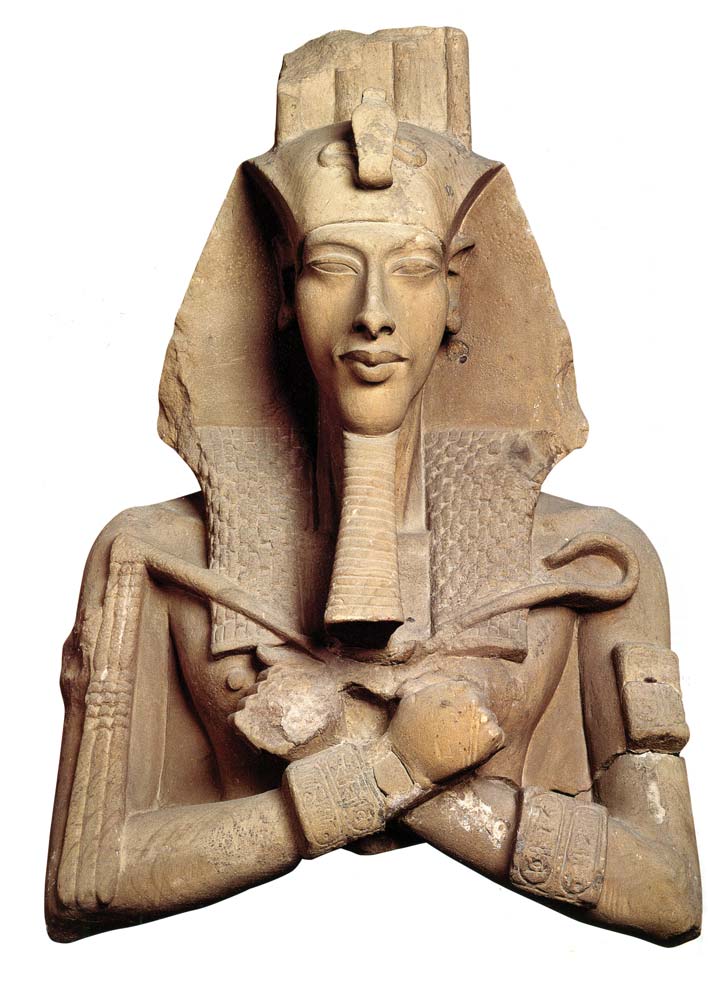

In Egypt and among the riverine civilizations, which were highly advanced in many respects, the concept of power remained deeply influenced by shamanic ideas. The role of Egyptian pharaohs and the interstitial priests, who acted as intermediaries between the known and unknown realms of sky and earth, held exceptional importance. The colossal statues of pharaohs, depicted in their most static and timeless state, convey a sense of timelessness without past or future. The very form of pyramids, advanced versions of ziggurats, similarly embodies this absolute stillness and timelessness.

There has been a long tradition of depicting tribal leaders and high priests in the Mesopotamian region. Most of these examples have been depicted in ceremonial contexts.

In the historical evolution of this civilization, mythical thinking and natural ethics (meṭīk) gradually gave way to clear directives of “must” and “must not,” which constitute a form of social morality with universal rules. This transition marked a distinguishing achievement of this center of civilization.

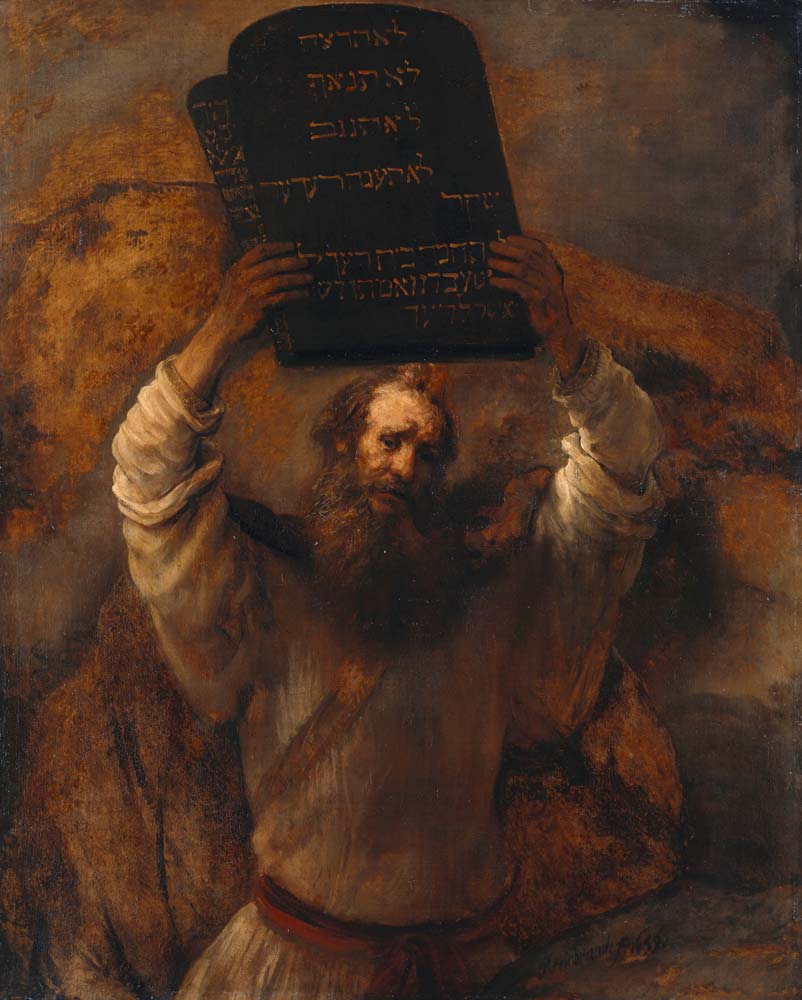

The period of Moses’ (peace be upon him) appearance represents a pivotal moment in the consciousness of the people of this region, marking a historic rupture. The outcome of this transformation was the emergence of the concept of “religious faith.” 5 The scattered tribes of the Children of Israel come together under a common covenant, reaching the status of a unified nation, centered around a concept of faith-based covenant. Those who remain steadfast in the covenant are considered believers.

In this cultural domain, literature within the branch of “sharīʿah” (religious law) expanded and flourished, with the highest global circulation of books being attributed to sacred texts. Furthermore, the sacred book holds significance as a historical document. The theological history within this book teaches that initially there was the Logos (Word/God), followed by Adam, the father of humanity, and subsequently the prophets, who establish a noble lineage.

With the advent of Christianity, this history takes on a linear form, meaning that at a certain point in time, a significant event such as prophethood occurred, and from then on, history progresses stage by stage towards the culmination, or the kingdom of heaven.

With the collapse of power in the advanced centers of Egypt, Assyria, Sumer, and Babylon, the tradition of depiction and representation also comes to an end in this cultural domain. In fact, visual art in these centers progresses to the stage of symbolic art.

According to Hegel, symbolic art finds its representation in the existence of the Great Sphinx. The Great Sphinx itself is a symbol of symbolic representation; it is where the spirit strives to emerge from the animal realm and enter into the human world. Egyptian art illustrates that this achievement was not fully realized in Egyptian civilization.

The evolution of awareness in this cultural center led to the idea that what is eternal is the divinity of God. God does not abandon humanity; humans can be listeners to the word of God. In this new realm of awareness, God manifests in His names and not in images or forms. His presence is perceived in commandments or in the words of celestial books. Manifestation occurs in abstraction, not through visualization or embodiment.

Regarding a specific example in Christianity, which although originated in this cultural center, its main branches that carry the meaning of embodiment were established elsewhere and influenced its cultural foundations. This faith-based thinking reaches its fullest form when it considers sculpting statues as forbidden and regards any likeness of God as fundamentally blasphemous. Following this transformation, the role of the prophet, as the person who hears the message from the source of life and delivers it to the people, becomes prominent. If people understand and believe in the message, they are freed from confusion through that intercessor.

Thus, the prophet becomes the focal point of the return to the origin after a long journey.

A column containing laws attributed to Hammurabi, one of the rulers of Babylon circa 1749-1792 BCE, was discovered in excavations at Susa. It includes 282 laws and descriptions of punishments for each offense. Among other findings in the Mesopotamian region, it appears that these laws were the result of compilation and revision of various regulations across civilizations in this area. A significant portion, nearly a quarter, of the laws on the Hammurabi Stele deal with inheritance, marriage, adoption, divorce and separation, and the ownership of slaves. This reflects the definition and importance of family structure in that era.

In the Mesopotamian region, legislation within the branch of “sharīʿah” gradually expanded, replacing mythical thinking and natural ethics with clear directives of “must” and “must not.” These directives constitute a form of social morality with universal rules, marking a distinctive achievement of this center of civilization.

Cultural center of Hinduism

The Himalayan mountain range in northern the Indian subcontinent retains moisture and brings monsoon rains over the land of India. The vast Indian subcontinent with its long coastline is a fertile land with highly fertile soil, and extensive parts of its southern lands are even considered among the regions that are free from any form of effort.

The first great civilizations of the Indian subcontinent emerged in the Indus Valley around five thousand years ago, contemporaneous with the burnt city of Iran (Susa), with which they had close interactions. For millennia, India was the eastern neighbor of the land of Iran. There are numerous linguistic connections between Sanskrit and the Avestan language. Similarly, new sciences that extracted myths from Iranian sources have shown us that Iran and India likely shared common myths in ancient times.

Hindu culture and thought, as mentioned, straddle the border of two vastly different realms. On one hand, it is the creator of grand and intricate sculptures, and possesses a logical prowess that contemplates and depicts the cosmic universe in the Upanishads, and brought forth the rich Sanskrit language. On the other hand, it has roots in contemplative passivity that sees the creation of the universe as a result of the playful cosmic dance of the great god Shiva, which occurred in absolute joy and purposelessness through the rolling of the dice.

In Hinduism, “Prakriti” (nature) is that which is born and eternal—meaning not in a state of becoming, but pre-existing. All other things are “Samsara,” cosmic bubbles that, like ripples on the surface of water, appear momentarily and then disappear, leaving only the eternal sea of the cosmos.

In Hindu culture, there are seeds of epic thought, but with the distinction that here we encounter a cosmic epic where gods are the main protagonists.

India is a land of myriad diversities, and one of the manifestations of this diversity can be found in the beliefs of Hindu culture, which are not uniform and unified. Across this vast land, offerings are made to various gods, and rituals, beliefs, and stories vary widely. There has not been a concerted effort in this culture’s foundation to standardize beliefs and unify them, and attempts to do so have often been unsuccessful when confronted with divergent perspectives.

Throughout history, there has been an intermingling of Buddhist thought and later Islamic thought with Hindu culture. Among different states in India, there is no common language or script, and shared festivals and rituals are mostly limited to contemporary times.

The culture of India carries roots of epic grandeur, as sung in the verses of the Gita and Upanishads. It should be noted that we are dealing here with a cosmic epic that unfolds in the heavens, involving interactions between gods or where gods play a fundamental role. This epic finds its earthly manifestation where gods incarnate in human or animal forms. Thus, Hinduism presents us with the concept of “avatar,” where a divine entity descends to earth in a tangible form. (Similarly, in Buddhist beliefs, the Dalai Lama is considered a representative of a transcendent incarnation on earth.)

In Hindu thought, the concept of “Yugas” or cosmic cycles unfolds through the play of Brahma, representing different eras or phases. The four stages of the Yuga cycle are known as “Satya Yuga,” “Treta Yuga,” “Dvapara Yuga,” and “Kali Yuga.” These stages depict different epochs characterized by varying degrees of moral and spiritual decline, with Kali Yuga considered the darkest and most turbulent phase.

Ancient Indian astronomers and mathematicians attached great importance to calculating cosmic cycles and preserving numerical values associated with each era. These efforts led to significant advancements in mathematics and numerical computation.

As we observe, the concept of cyclical time in Hindu belief suggests that humans originate from a primal state, descend, and eventually return to it. This idea of cyclic return to origins and beginnings also has a biopsychological aspect in our existence, mirrored in the life cycles of living beings on Earth. Tortoises, certain birds, and fish autonomously and regularly traverse circular paths throughout their lives.

As mentioned earlier, human separation from the natural state specifically highlights the concept of “time” in their consciousness. In Hinduism, this time manifests cyclically and continues within the framework of nature. Mount Shiva resides atop the Himalayas, and the holy waters of the Ganges originate from this sacred mountain. Annually, throngs of people gather in Benares (Varanasi) to purify themselves in this sacred river. This recurring cycle symbolizes the primordial event of creation: the separation from Brahma, descent, and return to him.

from the shapeless and endless waters? Who can enumerate the passing ages of the universe that continuously appear one after another, endless and infinite? And who can travel across the vast expanses of space and attempt to count the universes standing side by side, each with its own Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva? And who can count these Indras, who rule over countless worlds within the expanse of the universe?

The life and reign of one Indra equals seventy-one cycles, and when twenty-eight Indras have passed, one day and night of Brahma has elapsed. Yet the existence of one Brahma, measured by the day and night of Brahma, is only 108 years. Brahma follows Brahma, one sitting down while another rises; this entire sequence is beyond verbal expression, with no end to the count of Brahmas, let alone Indras.

[…] Armies of universes and realms come and go, like small bubbles on the vast expanse of the pure waters that form the body of Vishnu. From each pore of that body, a universe unfolds like a bubble, lasts for a moment, and then disappears into obscurity. […] Life within countless cycles of rebirth is akin to the embodiment of a dream. Gods residing at the peak, trees, and silent stones of the earth are merely reflections and spectacles in this illusion. […] Death reigns supreme, determining the fate of all. Cycles of alternating good and evil come endlessly one after another. Therefore, the wise person is one who does not become attached to either of these two transient poles, neither to good nor to evil. Wise ones are fundamentally unattached to anything.”

This excerpt touches upon the cyclical nature of creation, the vastness of the universe, the roles of Brahma, Vishnu, and other deities, and the philosophical concept of detachment from transient worldly phenomena.

A part of a mythological story in the Brahma Vaivarta Purana.

In some branches of Hindu thought, humans are not accidental but ancient. Samsara, the cycle of life and death and the transmigration of the soul from one body to another, continues until the soul is purified of impurities and ignorance. This cycle of samsara operates based on “karma,” or the law of cause and effect. Belief in the concept of reincarnation and the samsaric cycle separates the essence of soul from body. Thus, a Hindu’s body may exist in the Kali Yuga era while their soul progresses through other periods. Practically, this belief fosters resilience in enduring life’s hardships and adversities. Concurrently, this belief system engenders a disposition and awareness rooted in “non-attachment.” Gandhi, masquerading as a jurist, revived this collective spirit, which was a form of non-violent struggle or negative combat against modern ethical norms, unveiling new potentials in this cultural trait’s powerful essence from Indian culture, culminating in the independence movement of this land. Thus, we observe the peaceful coexistence of the poor and the rich, or followers of various religions side by side, stemming from the inhabitants’ awareness of the concept of “time.”

Artistic work is one of the most prominent manifestations of a culture’s unique understanding of “time.” The cyclical concept of time in Indian culture is imbued with the spirit and artistry of its people. Repetition, reproduction, and rhythm are among the fundamental characteristics of art in this cultural hub. Colors symbolize the proliferation of Brahma, and the dancing form of Shiva, from eyes to fingertips, harmonizes with rhythmic cycles of existence. Indian music is polyrhythmic, and its performance can extend continuously for hours. It’s the only type of music where leadership of the performance shifts from the master to the listeners. The grand master initiates the rhythmic cycle from the center, while the disciples surround and echo this initial action with hand claps or vocal sounds, repeating and multiplying it, even altering it. We see that artistic work can be a kind of adapting collective spirit with their existential disposition. This disposition, which has emerged in this region, does not put itself in conflict with others and can repeat the same occurrence, a division that has appeared in its system of consciousness, with all its subtleties, in an orderly manner and in infinite reproduction.

The concept of “cyclical time” has evolved uniquely within Indian civilization, where the primary creation occurred in eternity, and subsequent cycles are considered manifestations of this original birth. Creation began with the cosmic play of Brahma, and the digits of his dice generate the concept of time. According to one of the computational texts from the 4th century AD, we are currently in the Kali Yuga era, an age characterized by darkness and endless conflicts, spanning 400,000 years. With the end of this era, time returns to the Satya Yuga, or the Golden Age, where Brahma himself resides. In Hindu terminology, this cyclical time is referred to as “advari,” a term associated with gambling. Brahma joyfully casts the dice Treta (three), Satya (one), or Dvapara (two), and these numbers manifest as cycles in his cosmic game.

Persian by Dara Shikoh, the son of Shah Jahan and a notable scholar. Dara Shikoh endeavored, under the guidance of a group of scholars, to unify the foundational principles of religions through understanding their commonalities. He was tragically killed in a fratricidal war with his brother Aurangzeb.

An excerpt from Dara Shikoh’s Persian prose in his work “Sirr-e-Akbar” (The Secret of Certainty):

“The greatest veil and the most obscure mask that conceals the true beauty of unity are the limitations and multiplicities that have appeared in the outer existence […]. They present the concealed as if it has come into existence externally, although the fragrance of external existence has never reached them. They have always been and will always be essentially non-existent, while what is present and visible is the reality of existence, but considered as veiled by the ordinances and effects of external things, not in terms of being devoid of them.”

Cultural Center of China

The vast domain of Chinese civilization in the Far East is another major cultural center from which smaller civilizations such as Japanese, Korean, Thai (Siamese), Vietnamese, and others have emerged. China is bounded to the southeast by the Pacific Ocean, to the east by the East China Sea, and to the north by nomadic Turkic tribes. The Himalayas and Tian Shan mountains form natural borders with India and Central Asia, respectively. This culture, at its points of contact with Indian civilization, has created Indo-Chinese syncretic cultures. Since ancient times, it has been connected via the northern route through the Himalayas (via present-day Afghanistan) with Iran.

In a land where Chinese culture has flourished, success is often linked to a climate that is temperate yet demanding in terms of irrigation requirements. The expansive geographical location of this land, situated on the fringes of the ancient world, has fostered a culture inwardly focused yet intimately connected to the broader world, where the opening of doors has historically marked periods of turbulence.

The cultural life of China has been shaped significantly by its mighty rivers. The earliest civilizations in China flourished alongside the Yellow River and the abundant waters that flow from the west, dictating the nature of China. The periodic floods of these rivers, natural disasters recorded throughout past centuries, have at times abruptly taken millions of lives. Destructive natural floods or deliberate sabotage of waterways have repeatedly altered the fate of empires.

The role of such a climate, where large rivers dominate the land, and harnessing water requires comprehensive technical and social structures, has been instrumental in shaping a hierarchical system from top to bottom and fostering a notable form of cosmic paternalism. Over centuries, the people of this land have meticulously carved numerous and countless waterways to control and mitigate the destructive and capricious floods, marking vast and endless efforts along its lengthy courses.

To a contemporary observer, the astonishing volume of these canals may appear as natural branches of the rivers. Moreover, immense canals for transportation using river water have been constructed through extraordinary excavation efforts. This extraordinary volume of excavation necessitated vast coordination and collective effort, involving all the people of this land under the command of a great Khan.

Before British colonization, the administrative language in India was Persian. Ancient records of the Indian diwan and inscriptions on public buildings were mostly written in Persian. The British colonial administration in India conducted Persian language examinations for hiring administrative staff for many years, with texts such as Saadi’s “Golestan” being among the sources.

The prevalence of Persian, which had a rich cultural and literary foundation, in India dates back to the time of Mahmud of Ghazni, who brought Persian poets and scholars with him during his military campaigns in the region. During the Ghurid period, which established a centralized state, Persian was the language of the royal court. Urdu, as implied by its name, emerged as a blend of Persian and local languages, lacking consistent grammatical rules.

One of the policies of the colonial era was to promote and encourage the teaching of Urdu in schools in Pakistan as a support for the indigenous language. After severing ties with Persian literature, subsequent generations faced this void, as Urdu lacked reliable written sources and literary traditions. Consequently, initially translations from English attempted to compensate for this deficiency, gradually replacing Urdu with English itself.

The first emperor whose name became synonymous with China unified the scattered tribes of this land through military power and severe suppression, enforcing a uniform monetary system, a standardized script, and even consistent units of measurement across the entire territory. Thus, the concept of “the Chinese nation” emerged through the imposition of centralized coercive forces.

The society of China, unlike India, is a society of absolute unity and uniformity. Diversity in artistic products and various branches indicates a type of awareness, but in China, we are faced with a uniform whole that is significantly monolithic in form and consistency. Artistic works not only across vast geographical extents but also throughout its long civilizational history are relatively similar and markedly less diverse. (Comparing Persian calligraphy, with more than 40 scripts and styles continually innovated, to China’s tradition of strong and extensive but less diverse calligraphy, illustrates this point for us.)

In the Confucian ethical system, harmony throughout the entire social network results from each individual understanding their natural position in every social relationship and adhering to it until death. These social relationships are categorized into five types: 1. The relationship between ruler and subjects 2. Father and son 3. Husband and wife 4. Elder brother and younger brother 5. Friend to friend In all these cases, primary duties are based on compassion of superiors towards inferiors and the obedience of inferiors towards superiors. The only relationship where mutual respect governs is the friendship relationship.

Understanding Chinese culture greatly emphasizes the importance of Dao (Tao). In Chinese philosophy, Dao is undoubtedly formless; it existed before heaven and earth, and its name is unknown. Dao is a name for the unnamed, indefinable, and unknowable. It is everything and yet nothing; always still and unmoving, yet flowing and progressing.

Chinese people perceive the world as an active realm (realm of action). What has shaped this world is “action.” However, this world is not the ultimate reality. To attain the ultimate reality (Dao), one must find a kind of emptiness within oneself.

Alongside Daoist beliefs, another aspect of Chinese thought manifests in the form of ethical teachings in Confucian wisdom. Confucius’ teachings embody the most solid paternal ethics; with directives that are coherent, unquestionable, and self-contained.

“Look at it, it cannot be seen – it is beyond form. Listen to it, it cannot be heard – it is beyond sound. Grasp it, it cannot be held – it is intangible.

It is invisible, and they call it formless. It is inaudible, and they call it soundless. It is elusive, and they call it traceless.

By embracing this ancient Dao, You can guide present actions.

From this, you will gain the ability to know the beginning of eternity. This is the foundation of Dao.”

Dao Dejing, translated by A. Pashaei

The Chinese thought is characterized by a cosmic paternalism. In Chinese consciousness, paternal authority assumes a prophetic role. The Emperor or Khan holds a rank between earth and heaven with profound spiritual significance. All cosmic forces are influenced by the Great Khan, and the nation follows his command. This top-to-bottom relationship is established in a hierarchical order that begins with the Khan and extends to the head of the family. The residence of the Great Khan and his family is a place closed off to outsiders. A child destined to become Emperor is separated from his mother. People do not and should not know about him. The Khan resides in the “Forbidden City.”

On the other hand, alongside this hierarchical system of obedience and paternalism, Taoist thought in China advocates a peaceful disposition. The Chinese philosophical system does not stand solely on the idea of dominating nature. Despite a long history of exploiting the earth’s resources and inventing technologies such as mining for salt and coal extraction, the Chinese spirit continues to harmonize with the natural order. China is metaphorically reconstructing its immense defensive wall, which in ancient times was painstakingly built through human labor over centuries to fend off northern invaders. Today, this reconstruction is done symbolically and through its enormous economic prowess rather than through military means.

In modern times, the steadfast nature of Chinese ideology swiftly transformed from Marxism to Maoism, through which a political system aimed at revitalization emerged anew. While Confucian ethics seemingly took a back seat, they were revived within a new framework. Under the shadow of this new ideology, Mao assumed the role akin to an ancient emperor, commanding vast populations to adhere to his will.

Laozi, in the opening sentence of the Dao De Jing, considers the definition of Dao as something impossible. Therefore, Dao remains veiled in a curtain of profound and eternal mysteries. The mysterious emptiness of the cosmos encompasses everything. Chinese painters depict this enigmatic emptiness, from which landscapes emerge within. Painting in the Daoist tradition of China is colorless, forming shapes on the white paper from black ink spots.

The dual concepts of “yin” and “yang” are fundamental in the Chinese spirit. “Yin” literally means the shady side, and “yang” means the sunny side. These two intertwine within the encompassing circle of time, observing each other’s essence. Establishing a balance between fullness and emptiness is the central theme in Chinese arts such as poetry, music, and architecture. In Chinese music, silence over melody takes precedence. The content of the Dao De Jing emphasizes non-interference of human intervention.

The spirit of Chinese poetry, as well as Japanese haiku, resonates with silence and tranquility. The Hanami festival in Japan involves sitting under blooming cherry blossom trees and listening to the sound of petals falling.

The school of East Asian garden design appears as if it has preserved a pristine corner of untouched nature. In this type of gardening, the importance of aged trees is magnified a hundredfold.

Japanese Zen-inspired sand gardens differ significantly from conventional East Asian gardens. There, the empty spaces amidst stones evoke an embrace of void around things. White sand beds, adorned with wave-like patterns, resemble water, encompassing stones and rocks like the ocean does the islands of Japan.

In the realm of Chinese painting, much like Daoism which lacks a beginning or an end, scroll painting depicts a natural scene that envelops both painter and viewer. Unlike Western landscape traditions where the painter stands as a subject and active participant in nature, the viewer of Chinese scroll paintings journeys through nature as a traveler. In Chinese scroll painting, the eye doesn’t anchor anywhere; instead, observation continues endlessly in all directions.

This scroll-like depiction reflects a distinctive understanding of East Asian culture. Here, there is a sense of a return to a distant past, but Dao, being both origin and destination, remains elusive. Thus, time lacks a definitive origin; it’s an expanse floating between two infinites. From eternity to eternity stretches a broad continuum, with a beginning and an end that cannot be named.

This concept of time in Chinese culture is not linear in the sense familiar to us. Time in the visible world of the East Asian spirit is measured in moments, moments that pass by. Chinese culture has amassed a valuable repository of various calendars and sophisticated timepieces to measure these passing moments from ancient times. Unlike the narrative history common in Western culture, Chinese culture does not adhere to a single chronological history; instead, it embraces thousands of precise and organized chronologies or calendrical systems.

Greco-Roman cultural center

The Greek culture possesses a pantheon of gods. The transformation and delegation of the roles of muses and primal archetypes to these gods demonstrate the evolution of consciousness in the Greek spiritual system. Here, the archetypes transition from abstract concepts to tangible incarnations, with each deity embodying a specific function that has become perceptible and measurable. This measurability and concretization indicate a stable state of the spirit in relation to the forms of nature.

In the Greek world, the dualistic divisions and the bifurcation of the world into physics and metaphysics lay the groundwork for philosophical thought. As seen in Plato’s explanation of the Forms, the relationships of our world are inverted; the tangible reality is perceived as the world of shadows (the real form—Reouolus), while in contrast, the higher realm assumes a true form—Ideolos or embodied existence. This seed of thought later, in its transfer to Christian Europe, provided the foundations for the idea of the incarnation of God in Christianity and flourished in the visual arts.

Art in Greek thought is understood as “techne,” which encompasses the meaning of “craft.” This “craftsmanship” stands in opposition to “nature” and inherently signifies creating something beyond what naturally exists. Thus, in the Greek sense of “artistry,” which implies a break with nature, an aspect of knowledge is also implicitly present. This knowledge generates “episteme” (pattern). Therefore, the historical chain of concepts evolving from “techne” in Greek culture to “technique” and later to “technology” in European culture points to a form of awareness focused on producible outcomes. These outcomes are the products of the mind and result from a kind of mental practice and discipline that the Greeks referred to as “askesis” (the roots of the words “sketch,” “exercise,” and “ascetic” are all derived from it). This internal practice was the seed that later flourished during the era of Christian-Germanic theology.

Apollo […] descended from the peaks of Olympus with an angry heart, bearing a quiver with both ends securely fastened and a bow on his shoulder. The arrows clanged on the shoulders of the angry god as he moved, passing like the night. Apollo came and took his place beside the ships and then released his arrow. A fearsome roar rose from the silver bow. First, he targeted the mules and swift dogs, then unleashed his piercing arrow on the men, and from that moment, the piles of wood used for burning the dead continuously blazed. The first song from the Iliad; Homer; translated by Saeed Nafisi.

Greek thought is based on the concept of “unity of beauty,” from which the special value of “harmony” is born. Harmony manifests on two levels: one in an initial unity where life is continuously intertwined with nature, represented by Apollo (the word itself means unity: ‘a’ as a negation prefix and ‘pollo’ meaning multiplicity). The rupture from this stage propels Greek thought forward in history, and Greek philosophy is considered the result of this initial break. From this rupture, a second level of harmony emerges in multiplicity, and human law begins to govern cities. In Greece, a special meaning of human communities develops in the form of the “polis,” where the concept of “demos,” meaning people or the public, appears. In this way, the “collective will” finds new meaning, giving rise to legitimate governance. However, what remains overlooked here is individual will. In the organic unity of the polis, a conflict arises that places the law of the gods/nature in opposition to human/city law. This conflict, unable to resolve into a third outcome from within itself, leads to the fall of Greece. From Hegel’s perspective, what crippled Greek culture was the lack of manifestation of “inner subjectivity” in Greek consciousness, which would give meaning to individuality and the person as an active factor, in contrast to the collective and majority will. Christianity fills this void with the idea that the grace of God can encompass every human individual, introducing the concept of individuality into European thought.

In the climate where Greek culture flourished, seeds of deterministic thought, stemming from common human archetypes, were nurtured. One manifestation of this thought emerged powerfully in the form of Greek tragedies. As Hegel pointed out, in the play “Antigone,” the fundamental challenge that Greek culture grappled with is portrayed as a tragic story. “Antigone” narrates the conflict between natural law and the law of the polis, or the world of night and day in Greece, where women, who have no citizenship in the polis, rule the family and the night world, while men govern the day world of the polis. Antigone (a sister wanting to bury her brother, who is deemed a traitor by the polis’ ruler) defies the city’s law by appealing to the divine/natural law.

The realm that transforms collective will into universal will can stifle the individual under the pretext of communal interests. The conflict between the human law of the city and natural rights was one of the reasons for the downfall of Greece.

Plato adopted certain concepts from Zoroastrian thought. His perspective on Iranian philosophy is rooted in his historical context, seeking to find answers to the conflicts within Greek consciousness through an external ideology. In Iranian thought, “dēn” (religion/conscience) resonates with the collective harmony, and disputes are categorized into four types: mastery over oneself, mastery over the land, mastery over the kingdom, and the rise of the sun of wisdom. In Plato’s interpretation, these correspond to self-control, courage, judgment, and wisdom. Additionally, “Fravarti” is equated with the celestial Forms, “dēn” with “eidos,” “Ahura Mazda” with “Zeus,” and “Vohu Mana” with “Logos.”

This internal weakness in thought coincided with another external event, namely Alexander’s military campaigns and the establishment of Hellenistic kingdoms. Unlike the Persians, Arabs, and Mongols who were equipped with theories of war and governance, the Seleucids not only could defeat Iran but also establish dominion over it. However, to govern such vast territories, they required large armies that practically emptied the small Greek islands.

A form of knowledge whose origins were closed within Greece continued its life and renewal in its motherland. It persisted in philosophical abstraction. Some cultures, like Greece and Egypt, have only one advanced ancient period and have not entered a later period. If there were fortuitous events in one of humanity’s communities, there is no assurance of later occurrences, nor is there a passing from an era of intellectual life.

Greece indeed represents a civilization and thought that came to an end at the beginning of the first millennium AD. Although the Greek language later evolved into one of the languages of Christianity (Orthodoxy) due to its intellectual capacities, Greece itself did not pass through the period of Christianity. This does not mean that the Greek people did not embrace Christian faith, but rather that they did not play a direct role in the intellectual debates, establishment of Christian theology, art, and culture of that era. Furthermore, in the last two millennia, no distinct style or founding school emerged in architecture and the arts in Greece; remnants of ancient structures such as those on the Acropolis hill in Athens exist, yet signs of their continuity into subsequent periods in any Greek city are absent.

The legacy of Greek civilization is transferred to Rome and expands into the dimensions of an empire. The Roman Empire is the founder of the legal concept that defines contemporary Europe. Roman law is built upon the notion of “authority.” In the Roman Empire, cultural embryos take shape on a global scale, imposing their laws, legal systems, language, dress, and rituals wherever they spread.

This cultural domain, which we can call Graeco-Roman from this stage onward, grew at the western borders of the Iranian world. In terms of historical continuity (meaning the continuity of life alongside change), it shared similarities and kinship with Iranian culture. This implies that the life of these cultures involves constant renewal and redefinition, which is possible through engagement with the “Other.” Both Greece and Rome engaged in dialogue towards the awareness that had taken shape in the Iranian domain, finding their own “Other” in Iran. This dialogue manifested itself in various dimensions such as war, diplomacy, influence, conflicting opinions, translation of texts, and so forth.

Greek and Roman historiography not only detailed the events of wars with Iran but also sensitively described and evaluated the customs and beliefs of Iranians from their own perspectives. We find traces of the ideas of the Magi in some of Plato’s thoughts, where he sought answers to challenges that gripped the Greek world. Later, during the period of intellectual renewal, Christian Europe returned to this tradition.

Ancient Greece has become a subject of study in archaeology and linguistics during a period of history. In the reconstruction of an independent country called modern Greece, and in the revival of Greece as a historical origin of Europe, the political will of Europeans, particularly the power of the Habsburg Empire, played a significant role. European scholars, after the Enlightenment period, paid particular attention to the revival of a historical center that could separate the definition of the roots of European civilization from the ancient East.

The theme of Greece and its recovery from the Ottoman Empire gained prominence at the Congress of Vienna in 1818, to the extent that Lord Byron, the English poet, passionately fought for Greece’s revival against the Ottomans. The groundwork for scholarly awareness about Greece from this point onward was laid by German and Prussian scholars, not the Greeks themselves.

Cultural Center of Iran

The central core of Iranian civilization formed on a vast plateau whose boundaries stretch from the seas in the north and south, the Jihun River and the cold lands to the northeast, the Caucasus Mountains to the northwest, and the mountains and forests of Zagros to the west until the Euphrates River, and extending southeast to the broad valley of the Sindh River. The enclosed nature of this region inclined its inhabitants towards the interior of the plateau. Other factors also played a significant role; the central climate of this land provided suitable conditions for life. Geological findings indicate that shallow lakes existed in this region in ancient millennia, including Lake Saveh, Lake Urmia, Lake Namak, Lake Hamun, and the lakes of Fars, remnants of which persisted until recent times. Early urban centers were established alongside these lakes. Archaeological excavations have uncovered artifacts revealing that Shahr-i-Sokhta near Zabol today was once a port city or a burnt city situated near water.

However, these climatic conditions gradually changed. The once fertile and expansive lands turned towards aridity due to climatic shifts, and one by one, the central lakes vanished. These gradual climatic transformations became the sources of cultural formation where dualistic and heroic ideologies took root. Central civilizations gradually confronted the reality that they could not rely solely on natural water resources such as rivers and lakes for their continued existence. The quest for water necessitated determination to confront forces that dried up and extinguished the world. The practical and tangible outcome of this creative struggle resulted in the birth of the greatest hydraulic civilizations. Moreover, these climatic changes, which emphasized the “human will” in seeking solutions for continued existence, significantly shattered the Iranian mindset away from its mythical world at an early stage.

Life continued in a state of natural order and mythical beliefs, characterized by a passive existence that jeopardized biological survival. Survival here required each generation’s continuous effort on projects that would benefit future generations, thus ensuring their prosperity. Iran, at a very ancient stage in its history, broke away from the world of myths and embarked on a kind of heroic history. Its champions were humanized heroes, and its central core was one of wisdom and problem-solving in the prosperity of the land, understood as a sacred duty. (We will delve further into Iranian myths and heroic history in future discussions.)

In this new awareness, humans acted by choice, constantly exposed to decisions. Common archetypes of “predetermined fate” faded into the background, thus the inclination towards tragedy did not play a fundamental role. Belief systems were more about “work”: battling drought through land irrigation, reforestation to rectify mistakes, and dedicating wealth or endowments to public services. In defining the order of the Iranian cosmos, forces of good and evil were engaged in a struggle across the breadth of history, without obliterating each other; this struggle was understood as the order of the world. However, in this worldview, Gitī is benevolent, there is no notion of descent, and the dualistic conflicts between substance and meaning, physics and metaphysics, are not recognized.

Here, temporal epochs are reconceptualized as a division of historical time into four periods of three thousand years each, without a belief in returning to the primordial age. Instead, in the Iranian thought’s definition of creation stories, the emergence of the universe, and ultimately its linear conception of time, we observe ideas that begin from the primordial and progress towards the ultimate.

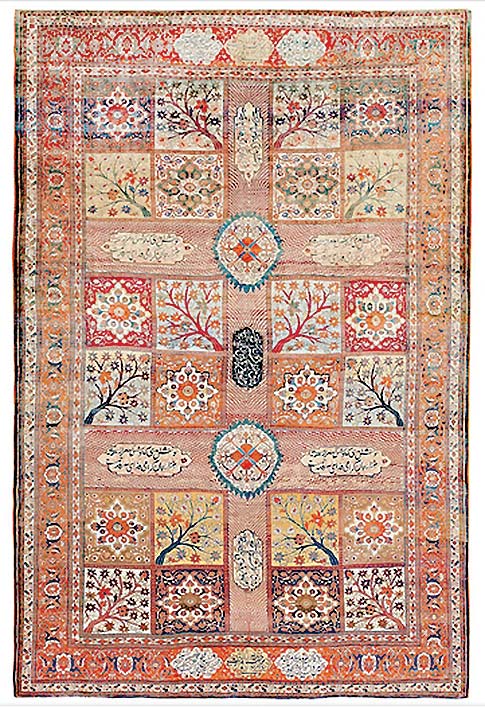

In this regional context, where diverse ethnic groups looked across their land and had extensive interactions, deep cultural affinities emerged among different peoples. Unlike other places prior to the establishment of national states, here the seeds of a “cultural nation” were intertwined, as extensively referenced by Hegel. Iran is essentially a nation of diverse ethnicities. The signs of this cultural nation are most evident in their cultural works. From the Caucasus Mountains to the Sindh River valley, musical melodies, architectural styles, handcrafts, and common patterns are shared. These meaningful commonalities simultaneously create a spectrum of diversity within. In this sense, the concept of Iran embodies multiplicity within unity, and unity within multiplicity.

The Iranian world is situated in the midst of a region that Gordon Childe has termed the “Golden Rectangle of Civilizations,” 6 spanning between the Danube, Nile, Jaxartes, and Sindhu rivers. Therefore, social, political, and cultural life in such a geographical position, positioned in the center of the civilized world, was intricately tied to news from beyond its borders. In this context, continuing life depended on staying informed about external developments, unlike the possibility of isolation as seen in the distant East.

Stories are essential in understanding cultures. One common way to begin stories in Persian is by using the phrase: “آوردهاند که…” (It is said that…). Likewise, in epic poems and allegorical tales, each story unfolds in different lands; in distant cities and other places.

Seven thousand kilometers of the ancient world’s ten-thousand-kilometer trade route were located within the Iranian world. Constructing and opening routes for communication in this geographical position had particular advantages. It influenced people’s perception of the vastness and diversity of the world and shaped their interactions with it.

In this context, the connection between unity and diversity leads to the emergence of a new concept of ownership, distinct from personal possessions such as tools, animals, wives, and children. On the verge of becoming a historical nation, people establish a relationship with a land whose boundaries and riches are determined not just by tribal and clan conflicts, nor solely by meeting vital needs. The meaning of land evolves from its initial form, which was tied to the natural conditions of daily life and the need for security and resource exploitation, to a new stage where the concept of “country” is born.

Major social contracts typically give rise to grand narratives. People gather around a collective narrative that often carries mythical aspects. One distinctive feature of Iran’s cultural domain is the establishment of a shared calendar and widespread communal celebrations across the land.

Understanding the essence of games is one of the key elements in comprehending the consciousness and psyche of any nation. Play is an active engagement through which people of a land create joy in relation to the instruments and methods of their livelihoods and lifestyles. Its propagation serves as a collective behavior and exercise that teaches meanings, nuances, appropriateness, and communal capabilities from childhood to old age.

Considering the artifacts we recognize from ancient Iranian civilizations in the southern geographical axis of Iran (such as Shush, the Tepe of Bikan in Fars, the Aratta civilization alongside the Helmand River in Jiroft, the burned city in Zabol, and Mohenjo-daro on the banks of the Sindh River), we become familiar with games that have their own distinct characteristics. Even the adoption and spread of games like chess, referenced in the Shahnameh, serve as a refined mental exercise that nurtures epic thought, problem-solving, and selection.

One of the important climatic factors that has influenced the shaping of cultures is water resource management. In Europe, the Dutch have endeavored throughout their history to reclaim water. Twenty-five percent of the Netherlands is below sea level, and water naturally permeates through its low-lying soils. The Dutch have developed creative techniques over time, digging drainage canals and constructing mills that set water in motion to dry the land.

These industrious people, facing unique challenges in a land area about one-forty-fifth the size of Iran, are today the world’s second-largest producer of agricultural products after the United States and the foremost producer of flowers, seeds, and onions globally.

In ancient Iran, irrigation was managed by choice, meaning access to water was achieved through deliberate effort. This way of life required tremendous effort and the application of various architectural, mathematical, calendrical, and agricultural skills. The integration of these practices with the people’s way of life was essential in fostering a spirit of heroic endeavor among them.

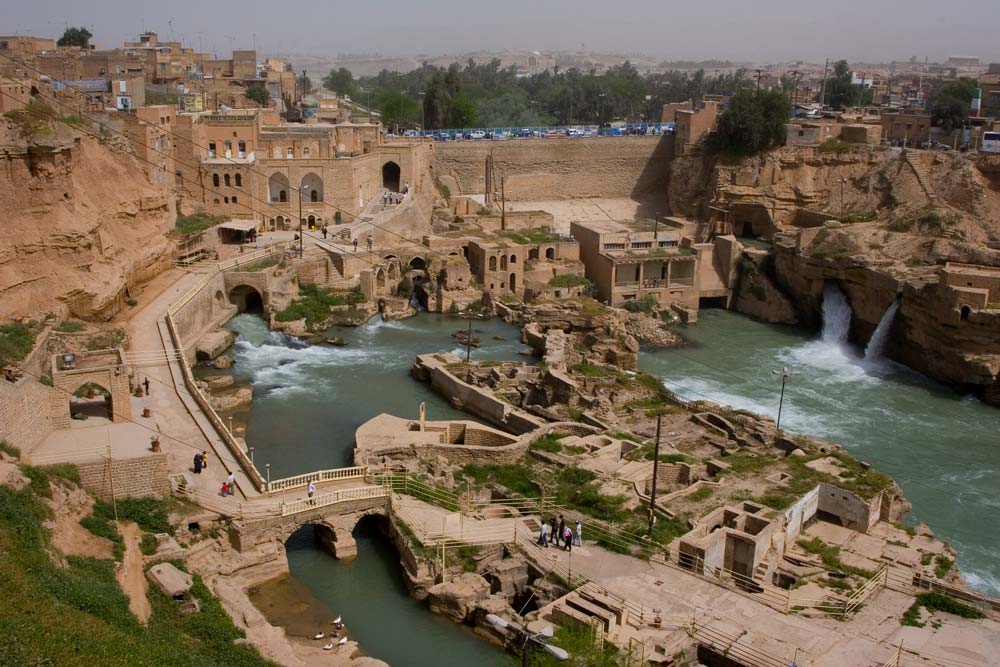

Water management projects in Iran have been diverse and monumental. For instance, the length of the Qanat Zarch in Yazd is about 100 kilometers. The depth of the Mother Well of Gonabad Qanat reaches approximately 300 meters, with its digging dating back to the second millennium BCE (consider that the depth of the Darasiyeh oil well in Masjed Soleyman is roughly the same). Water structures were not limited to qanats alone; water canals in Shushtar have a history dating back to at least eighteen centuries ago, guiding the waters of the Karun River to move massive stone mills. Similarly, the Nahrawan and Kandovan canals alongside the Tigris and Euphrates managed to prevent the lowlands of Iraq from turning into swamps by controlling the river floods (this problem resurfaced after the collapse of the Sassanian Empire and the neglect of these canals).