An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dadbeh

Since everything in the world possesses degrees of consciousness, natural consciousness might not be a suitable criterion to define the distinction between humans, animals, and plants. The behavior of materials convinces us that even inanimate objects have some degree of consciousness, and we know that animals possess memory, intellect, and emotions. Additionally, animals adapt to conditions by nature or, in other words, as a continuation of their natural state, or they undergo physiognomic changes in response to environmental hardships. Humans are similar in this regard, but what distinguishes them is the relationship they establish within themselves between themselves and the world. This characteristic enables humans to reveal the world that manifests within them through “naming.” This trait is different from the natural language of other creatures.

The source of this ability to name is the poetic nature of humans. Here, poetry is not considered one of the arts. It may seem logical to think that humans first created a linguistic system and then composed poetry. Still, from a phenomenological perspective, it is the poetic nature of humans that fundamentally enables them to speak. Something appears in human consciousness, and they name it. Naming itself results from their separation and detachment from phenomena. By naming, humans project their spirit (consciousness) into an external existence and seek to reclaim it. In this sense, the poetic human is a lover. Love is essentially a practice of awareness and human love for phenomena is a form of awareness. This intended role, which appears in their system of consciousness, gives their existence direction and a center, without which confronting the world would be terrifying. With these premises, one can have a different understanding of Hafez’s poetry: “Become a lover, otherwise one day the world’s affairs will end / The unpainted pattern of purpose from the workshop of existence.”

Love is a practice in awareness, and human love for phenomena is a form of awareness. The intended pattern that becomes evident in the system of human consciousness gives their existence direction and a center, without which confronting the world would be terrifying. The word “love” (عشق) is an Arabicized term derived from the Avestan root “ish,” meaning to desire. This word, with the suffixes “k” and “q,” appears in various branches of the Persian language, related languages, or neighboring linguistic domains. For instance, in Old Bulgarian, “ask” means desire and wish. In modern English, the word “ask” conveys the meaning of inquiry from the same shared root. 1

Regarding the Meaning of Discontinuity and the Concept of Historicity

The relationship between humans and the world is contingent upon their type of awareness. Awareness emerges in response to three questions about the essence of “being,” the essence of “human,” and the essence of “time.” Each nation establishes its unique relationship with the world based on the answers it finds to each of these questions. Thus, various forms of awareness arise corresponding to the historical experiences of different peoples, without any necessarily being superior to the others.

The study of the progression of various peoples shows that some civilizations advance continuously based on their initial responses, while others repeatedly experience discontinuities throughout their progression. These discontinuities present challenges for them to sustain and redefine their world, and to find new answers to the same fundamental questions. Hegel refers to the latter type of civilizations as “historical civilizations.” This term “historicity” does not mean merely “having a past,” as in the broad sense all peoples have a past.

The discontinuities that these historical civilizations encounter manifest in varying degrees and arise in conditions where a new concept comes into dialectical conflict with past awareness. The emergence of a new concept on the horizon of awareness can transform all dimensions of the spirit. However, this does not mean the eradication of past awareness but rather the transformation of old foundations. Therefore, for such civilizations, entering into new awareness without challenging the old awareness—which practically sets the stage for the discontinuity—is fundamentally impossible. Conversely, in societies with a non-historical nature, continuity does not occur based on discontinuity. An example of such an existence is the way the Chinese civilization interacts with the modern world. Some sociologists point out how the cultures of China and Japan have become schizophrenic in their encounter with the modern world; this means that in one layer, they continue based on ancient traditions, while in another layer, they behave entirely in a modern manner. In these peoples, technology can be utilized without the individual’s nature and psyche needing to have a relation to this new world. Thus, we see that some societies accept the rules of modern life with less tension without engaging with modern awareness at various levels.

Regarding Time and History

Time is not an objective and external entity but a subjective concept. It is said that God created existence, and humans created time. The concept of time is the result of the contrast and separation between humans and existence; consequently, any change in the relationship between humans and existence will also alter human understanding of time. In the mind of contemporary humans, the word “history” can explain the entire past of humanity. This correlation between the word “history” and “time” originates from the awareness of the modern era. In other words, contemporary humans define and classify the past based on this new understanding of temporality.

However, determining the starting point and categorizing historical periods within each branch of history depends on the subject and the theory under study, which can vary significantly. For example, for a historian (chronicler), the beginning of history coincides with the emergence of writing, meaning that history is a phase in which writing begins to occur. On the other hand, an archaeologist may see the beginning of history in the emergence of civilization, even if writing is not yet present. From the perspective of empirical sciences, history begins where humans start manipulating materials and extracting metals; from this viewpoint, the Stone Age humans are considered prehistoric. For a religious scholar, historical coordinates are defined in relation to the establishment of religion. For instance, for a theologian historian like Tabari, the mission of the Prophet of Islam marks the beginning of history, even though he also discusses the history of ancient Iranians and the pre-Islamic era.

The subject of these lectures is the history of culture and art, and here we endeavor to create meaningful classifications to better understand the progression of awareness and its manifestations in art and culture from ancient times to the present day.

The cosmic era

We begin our journey of awareness from a very ancient period; an era predating the emergence of tribes and divisions—a vastly long period spanning millennia, which can be referred to as the cosmic era. The ancient patterns of the cosmic era are shared among all humans and common myths across various cultures have their roots in the memories of this long period.

The cosmic human lives in a timeless state. There is no separation between them and existence. Therefore, their two main characteristics are a lack of awareness of “time” and a lack of questioning about “humanity.” They see themselves as inseparable from the cosmos. Homer’s Iliad discusses the “timeless state,” describing how ancient humans, or cosmic humans, considered themselves belonging to and part of the cosmos, without seeing a separation between themselves and the world.

The separation from existence constitutes the greatest and oldest dread and fear of humanity. This is the same horrifying and terrifying world of awe and fear that Schopenhauer speaks of. The inclination to escape from this profound fear sustains the cosmic human in a timeless state of eternal present. The actions of the cosmic human are a repetition of the primal act. Traces of this existential state still linger in the art of some civilizations.

The cosmic era is a period without narrative and predates storytelling, marking a fresh stage in our understanding of the concept of “time” concealed within the act of narrating. Awareness of time emerges from the confrontation between humanity and existence.

In Hindu-Vedic civilization, vocal music known as “Om chanting” originates from the primordial sound that first manifested in the visible world; or to put it more precisely, the repetition of the eternal sound. The rhythmic form of this music, as well as the music of mystical circles, akin to the music of primitive tribes, has its roots in the repetition of the primal act.

This repetition and rhythm in ancient arts signify the manifestation of existence, where there is no questioning within the repetition itself.

In this sense, from the gap between human and nature, one arrives at the realization that existence is ancient, and humanity is ephemeral. It is uncertain how many millennia humans have carried within themselves the anguish and fear of separation, as if solitude is an essential part of the archetypes of the human soul, still visible in art today

Certainly, a clear and distinct boundary between ancient eras cannot be drawn, but we can conceive that with the emergence of the first fundamental questions, a new era began. Perhaps the first fundamental question of humanity was indeed the inquiry into the essence of existence.

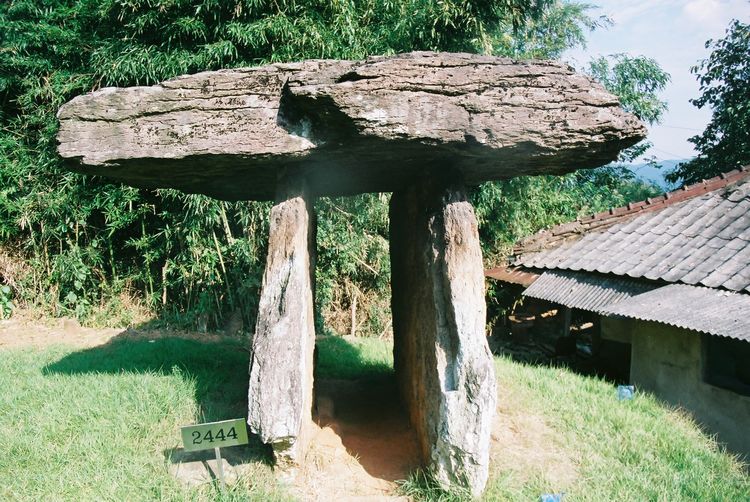

At the farthest boundaries of the transition from the cosmic era, colossal structures built by humans have been discovered, with remnants found from the British Isles to China in the East. These structures, which are massive and permanent stone constructions, appear to have been used for some form of early observation. They can be considered as markers that humans used to identify their coordinates in the boundless expanse of the earth. Thus, these structures indicate social centers at the dawn of humanity’s engagement with the questions of existence and their own nature.

The Age of Mythology

During a gradual process, a new stage of human awareness emerged, which can be termed as the mythological era. Humanity separated itself from the timeless and ventured into the realm of multiplicity, marking the beginning of myths. The Greek term “mythology” and the Avestan term “mythokht” both derive from the ancient root “my”, which carries the meaning of intermediary and mediator.

In essence, myths exist as intermediaries between a primary truth and a secondary truth, possessing a reflexive quality where humans perceive their own awareness within them. Myths are constructs and representations of the human psyche at a stage of awareness that requires intermediaries to discern and name the functions of the world — falsehoods that cloak kernels of truth.

In Sanskrit, we see “mitra” (= connector), in Avestan “mithra” (= mediator and friend), and in ancient Persian “mis” (= covenant). Another manifestation of this prefix is the word “midez” (= to be in the middle) in ancient Persian, which is the root of modern Persian words such as “miz” (evolved pronunciation of midez), “miyan” (between), and “meydan” (field).

In Greek, the word “mesites” (= arbitrator and mediator), which later in Roman times was used as the title “Mithras” (and its own family name), is derived from the same root.2 These include words like “media” and “medium” in modern English derived from this common root “mi”.

In the images created based on ancient patterns, we see this semantic coherence where even through subsequent eras, sometimes with the loss or transformation of original meanings, repetitions occur. The ceremony of communion in the Mithraic ritual is depicted around a table (the words “mass”, “Mithras”, and “table” all signify mediation). Depicting Christ seated at a table during the Last Supper follows a similar pattern (the name of Christ in Eastern Iranian languages (Sogdian) is “Meshi”, and in Hebrew “Mashi” or “Misha”, all meaning mediator).

The emergence of the words “قصه” (qesseh) in Arabic, “story” and “history” in English indicates that humans have moved beyond a period of mere narration. The Arabic word “قصه” and its ancient roots such as in the Eritrean language derive from the root “يَقص” meaning to follow or seek something until its origin is found. Similarly, the Greek “history” (ἱστορία), Latin “histor” and English “story” all carry this meaning.

Here, a mistranslation has occurred: the word “history” in translating Greek texts to Arabic was transformed into the word “اسطوره” (myth) instead. Whereas “ميث” and “ميتوخت” both derived from the ancient root “مي” mean mediator or intermediary, not falsehood or myth. As the wise have said: “Do not regard it as falsehood and myth, Read it clearly in accordance with the era. Whatever you perceive with wisdom, It reveals another path and meaning.”

As Eliade mentions in his study of the history of religions, the initial beliefs, such as various forms of shamanism, are monogamic and contain a form of unity delusion in their worldview. In more complex manifestations later on, pure apparitions, various natural forces, and their powers are re-recognized and differentiated; the transformation from thunder and lightning, water, fire, and so on, into myths/stories marks an important intellectual shift in this era.

It is through these “intermediaries” that the human psyche becomes manifest: dancing, singing, composing poetry, building temples, and creating art. Each of these arts has its special relationship with “time.” For humans who have separated from the world of unity, new aspects of the concept of time take shape:

As mentioned earlier, in the first step, humans come to understand that existence is ancient and they are contingent; that is 3, they have been thrown into this world. 4

Thus, in this newfound understanding, seeds of the meaning of origin and beginning sprout. Among cosmic humans, there are also shades of the meaning of origin, with the difference being that they themselves stand at the origin. They fear the rupture and throwing into existence and do not want to face this separation. We find traces and signs of this spiritual rupture and the pain of separation in mythical eras in ancient rituals such as birth, death, cultivation, consumption, sacrifice, and so on.

About the concept of center and coordinates

From the very early stages of familial bonding to the emergence of tribes and nations, human life has been communal. In terms of civilization, the concept of power takes shape naturally. Myths are both the result of communal awareness and a product thereof. The tent of the shaman served as the center and sacred space for early gatherings.

The center pole of the shaman’s tent represents the focal point of the communal circle. The shaman, their tent, the central pole, the sacred space, and other symbols form the foundation of this primal system of power. Each member of the tribe transforms themselves into a myth through the use of masks, clothing, and body painting, elucidating a principle of cosmic order.

Gatherings around the central pole of the shaman’s tent or a blazing fire involve ritual dances. Dance is among the oldest human behaviors. A common characteristic of the archetype of dance is its representation of human disorientation and celestial rotation, indicating directions. Through rhythmic movements, humans have sought to discover their relationship with the world.

These dances are performed to maintain harmony with nature, light, and fire, aiming to overcome the bewilderment caused by separation. Bewilderment is the result of newfound awareness during this period. The shaman of the tribe mirrors this communal bewilderment. The shaman transforms into a myth of profound intellect, riding on wooden sticks during rituals, climbing trees, or conveying their spirit through unusual states of flight.

The tent of the shaman transforms into the sacred place or center of power within the tribe, and the “center” is what brings coordinates into existence and establishes relationships. However, our relationship with existence is always changing. Thus, throughout history, every transformation in human awareness has altered their definition of coordinates and consequently transformed the concept of time.

For example, Copernicus changed the prevailing belief that the Sun revolves around the Earth, altering humanity’s relationship with the universe. In a more abstract example, Kant defined the human mind as a center of coordinates, transforming our existence in the world. Marx criticized Kant’s framework, demonstrating how he was practically laying out new coordinates.

Marx states: “Where hitherto the human stood on its head, henceforth it will be standing on its feet, so that it see the real world in an upright posture.” Bohm, a physicist, in his theory of implicate order, refers to the story of Helen Keller—a blind, deaf, and mute girl whose cognitive pathways to the surrounding world were blocked, yet she managed to achieve high levels of education. He asks how Helen became knowledgeable and wise, how her spirit manifested within her. Bohm finds the answer in the place where a teacher helped her find her spiritual place, miraculously bringing her out of the silent world because the reflexive and reflective nature of the human spirit requires more than just seeing and hearing; it necessitates being situated somewhere.

Climate conditions play a significant role in shaping the concept of coordinates in the mythic era. Climate has always provided the first coordinates to humanity. Natural features such as mountains, rivers, and generally everything in the sky and on the ground have been used in this regard. Primitive humans initially perceived the earth as a reflection of the heavens. For them, the ultimate truth resided in the skies, and what happened on earth was seen as a shadow of that truth. Before humans themselves became intermediaries between these two worlds, mountains, rivers, trees, and other elements played the role of intermediaries or myths.

“The tree” has been one of humanity’s oldest myths. The physical characteristics of a tree, which rises from the soil with its branches reaching towards the sky and roots deep in the earth, provided mythic coordinates for the mythic human. We still see the sanctity of trees among certain groups of people, such as Native Americans and ancient Slavs of Eastern Europe. The remnants of this ancient myth are alive in the tradition of decorating the Christmas tree or using old trees as intermediaries for fulfilling wishes.

Another significant myth is the “river,” which governs human life. For example, in Egyptian civilization, the Nile River enabled agriculture and, more importantly, sustained life. The Nile flows from south to north, forming an axis perpendicular to the sun’s trajectory across the sky. This creates a life-giving cross or mandala, away from which life is impossible. To the west of the Nile lies the waterless and dead Libyan desert, a place of exile for sinners, while moving eastward leads to the salty sea. The unique geographical position of Egypt meant that early Egyptians had little contact with other civilizations. Life in this land was only possible along the Nile’s banks. The Nile flooded twice a year, spreading fertile black soil on its banks and enabling agriculture. In this world, the boundary between life and death was very clear. One could stand in Egypt with one foot on the black fertile soil and the other on the red barren soil. The primary colors in Egyptian painting were also black and red.

In the sacred sites and temples of the Egyptians, almost all of which are tombs, the symbolic meaning of these two colors in the ancient Egyptian world is evident: the world of the dead, the world of the living; red and black. The river’s repeated floods set the cycle of life and death in motion, as if everything moved and returned with it, giving shape to the idea of reincarnation. This vital cycle shaped the concept of time for the Egyptians. Egypt is a good example of how environmental conditions influence the creation of myths and how the concept of the center is crucial for the direction of each culture.

Another manifestation of the concept of the center for the mythic human is the “mountain.” The mountain is an initial refuge; waters flow from it, making it the source of life. For the human of this era, who defines life in relation to the sky, the form of the mountain, sturdy and pointing towards the sky, is influential in shaping this role. The architectural design of sacred places in the ancient world follows the mountain form. The construction of ziggurats in ancient American civilizations (Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas), Mesopotamia, and Egypt follows this model. References to sacred mountains are found in the myths of various peoples. For example, Iranians call Mount Alborz the navel or center of the world in the Avesta, Hindus hold the Himalayas sacred, Armenians venerate Mount Ararat 5, and Germans revere Mount Himmelberg. For the Israelites, Mount Sinai is significant and holy. In the Old Testament, Noah’s Ark is built on and then rests on a high mountain. In Iranian myths, Jamshid constructs Var Jamkard as a refuge in the mountain to protect against the evil of three winters and ice ages, gathering the seeds of plants, animals, and the best people there.

Mehrdad Bahar points out that the myth of Haji Firouz likely entered Iranian culture from the spring festivals of ancient Egypt. Haji Firouz himself is black and wears red clothes. He emerges from the darkness of the dead earth, dancing and heralding the news of life.

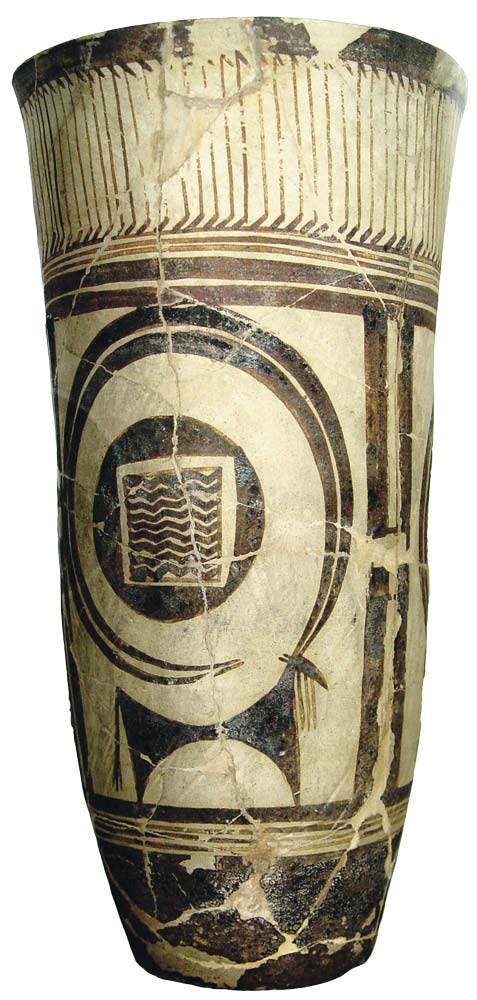

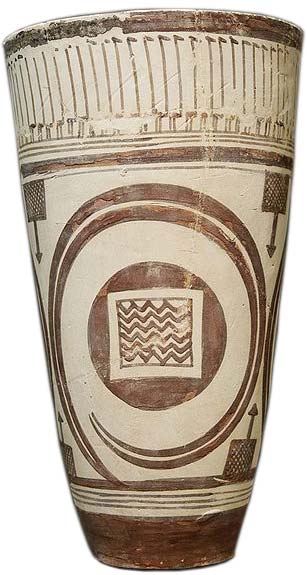

Humans have always needed to categorize the various aspects of their surrounding world. Each type of categorization both requires and simultaneously constructs a set of coordinates for their own spirit. On ancient pottery, we see many designs with various fourfold divisions. In fact, the division of the inhabited world into the four natural elements (the four sacred elements) has helped humans recognize their own existence. Most designs on early pottery depict the behaviors of nature. In these motifs, we find conventional forms for representing wind, earth, fire, and water. For some cultures, these elements are four, while for others, they are three or two. In Iranian mythology, a fifth element named “Apan Nabat” appears, which is equivalent to the tree myth in Chinese culture.

Humans observed animals such as lions, goats, scorpions, and snakes on earth and found their likenesses in the stars and constellations, perceiving these heavenly forms as eternal representations of these creatures. From their perspective, celestial functions manifested in earthly animals and beings. This allowed them to establish a necessary relationship between their own time and the eternal time. The Chinese calendar, which assigns its divisions to twelve animals, exemplifies this connection between heaven and earth. 6

This process of transferring the roles of the heavens to the earth occurred through intricate stages, ultimately shaping human spiritual life through lived experiences. This progression also demonstrates how mythological humans were engaged in recognizing, organizing, and naming the functions and characteristics of the world.

Some animals that carry mythological significance have been universally present, such as the snake, which is often associated with life and, for some cultures, with death. In the ancient Eritrean language, one of the oldest human languages, the word for snake means “life.” Similarly, in Arabic, the word “ḥayy” means both “snake” and “life.” In Persian, this primary meaning can still be seen in words like “bimār” (patient), where “mār” refers to snake. This mythological role likely relates to the snake’s movement, resembling flowing water, and its ability to shed its skin, symbolizing rebirth and immortality. Additionally, for mythological humans, the coiled shape of the snake suggests the cyclical nature of time, which is why it is used today as a symbol for infinity. Similarly, the mythological significance of the snake can be observed in the design of medical symbols.

These intermediaries often appear as motifs of trees, animals, plants, or the colors of the three or four elements and are used today in collective symbols like national and ethnic flags. These symbols usually include ancient archetypes that continue to be collectively accepted by the communities they represent.

About Time and Counting

As previously mentioned, the motifs on the oldest pottery primarily depict elements of nature, with minimal representation of humans. These motifs gradually reflect new experiences of the time. Eventually, human figures alongside domesticated animals, which had been separated from the wild, begin to appear on pottery. The emergence of each new animal and plant motif on pottery indicates a period of transformation in human life. These motifs signify the taming of animals like cows, roosters, horses, and dogs, the cultivation of grains, and even the beginning of storytelling.

Perhaps the inclination towards storytelling arose from an initial sense of leisure. One of the oldest known stories is that of “Gilgamesh.” This story represents a shared archetype among various cultures, with similar tales found in Central Asia, Sumer, and even among the indigenous peoples of Australia. Examples include Baal, Tammuz, the dying god, the story of Siavash and his rebirth from a plant, and the tale of Kiumars. All these share a common structure with the Gilgamesh story. The core essence of these stories involves separation from the origin, a journey, initiation, a new understanding of the world, death, and return. The archetypes in the story of Gilgamesh are related to humanity’s confrontation with “death.” Henceforth, the quest for “eternal life” becomes a recurring myth.

The hero’s step-by-step journey, involving various stages, reveals a different understanding of time. In these narratives, the hero finds a place to settle and an origin; then, the hero departs from this origin, traverses a path, and leaves something behind. The hero experiences the sorrow of separation, and the community, having lost its hero, awaits his return. With the hero’s return, the collective awareness changes, as he has left the origin, undergone initiation, and returned with a new form of consciousness. The stages of the “seven trials” seem to be the destiny of all subsequent heroes and champions.

The story of Gilgamesh conveys a universal archetype among various cultures and pertains to the era when humanity confronted “death.” This journey narrative centers on a human who has now settled in a place and found an origin. The hero departs from this origin and traverses a path, experiencing the sorrow of separation. The community, having lost its hero, awaits his return. Upon the hero’s return, the collective consciousness changes, as he has been initiated into a new understanding and comes back with a fresh perspective.

The step-by-step journey of the hero, completed through various stages, inherently carries a new perception of time. The progression through the “seven trials” seems to be the destiny of all subsequent heroes and champions.

One of the most renowned manifestations of the archetype of confronting death is evident in the story of Noah the prophet. He saves a sample of all creatures in the ark from death. Similarly, in the story of Jam, this narrative is reflected where good plants, righteous humans, and animals are saved from the harm of a prolonged winter and freezing conditions.

The desire for immortality also manifests in the creation of inscriptions addressed to future generations, carved into the hardest stones, so that the names and deeds of ancestors are remembered. These ancient forms of consciousness continue to exist in modern forms at various levels, whether through science fiction stories about time travel or certain scientific projects, the archetype of striving for immortality is evident.

For example, NASA’s Voyager spacecraft carries information in the form of metal plates with engravings, images, and sounds from life on Earth, representing humanity and its way of life, sent as a message to future beings or other entities beyond the solar system.

Many patterns from this ancient era still flow within our psyche. The mythical human found dualities in the universe that remain strong in our awareness. The questions of life and death are persistent queries for humanity. The dualities of existence and non-existence, day and night, darkness and light, later shaped the dualistic consciousness, a more advanced form compared to the monogamous illusion of the shamanistic era.

The topic of birth and procreation extends the question of life and death. Procreation in human consciousness has been linked to the dual factors of masculinity and femininity. Humanity perceived the masculine and feminine qualities throughout the entirety of existence and understood their repetition in humans as a reflection of the celestial pattern. From this dualistic consciousness, humans have named the world around them, attributing masculine and feminine aspects to everything. In the history of language, there is no language that in its past did not have the characteristic of distinguishing masculine and feminine, unless it traces back to a consciousness before this period (such as the languages spoken on some remote islands).7

The earliest enumerations are the result of humans questioning life and death, existence, birth, and reproduction. The concept of enumeration is uniquely human. In animals, enumeration does not imply understanding the sequence of numbers (one after another) and does not lead to cognition. The ability to count in humans is due to a rupture that separates them from phenomena.

In the cosmic stage, before enumeration, natural forces were infinite and beginningless. Rivers flowed without end, mountains stood steadfast in human memory from time immemorial, and there were day and night, and seasons that followed one another. Humanity existed in a timeless and beginningless time, in a primordial time.

The spiral form symbolizes and signifies this timeless time. Humans perceive this form in the movement of wind, the swirling of whirlpools, the coiling of snakes, the shape of goat horns, snail shells, and other rotating forms in the sky. The repetition of motifs, like the encircling tent of the priest, refers to these intricate and upward spirals of branches and leaves of trees that start from the ground and continue indefinitely.

Brancusi sought to attain pure and primal forms. Many of the sculptures he created were influenced by the indigenous art of primitive peoples. His work, in some respects, resembles that of his compatriot and mythologist Mircea Eliade. Both endeavored, through stripping away and refining raw material, to reconnect with the minds of creators from prehistoric times and grasp the pristine forms that are the common denominator of the diverse cultures and varieties existing today.

Eliade expressed regret that he never met Brancusi. According to him, Brancusi’s work was a quest to find his place in the world, akin to the striving of ancient humans.

Entry into measurable and finite time has been one of the significant stages in the evolution of the human spirit. Among the most crucial natural phenomena that enabled timekeeping was the changing phases of the moon. During this era, humans found the most tangible and trackable form of natural transformation in the moon. Few cycles of change in the universe exhibit such simplicity, stability, visibility, and measurability. Calculations based on the movement of the sun became feasible much later. The moon is born, transforming from a delicate crescent to a full disk, then wanes into darkness before returning anew. It seems like a celestial mirror reflecting the cycle of life and death in agricultural life on Earth.

Among the phenomena that provided a measure of time were pregnancy and childbirth. The cycle of reproduction gradually defined and conceptualized time. It is likely that mythical humans gradually discovered a relative connection between the lunar celestial changes and the earthly feminine cycle. Today, lunar calendars still govern pregnancy timing rather than solar calendars. Analogies reinforced this connection; the resemblance between the crescent moon and the form of a fetus (often seen in miscarried fetuses) took on significant meanings. During this era, the dead were often buried in coffin-like tombs resembling the fetal position.

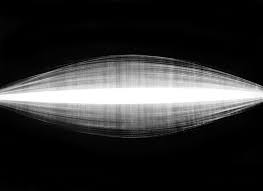

The crescent moon is perpetually in a cycle of birth and return. 9 The Vedic symbol “Vesica Piscis” is widely observed in Hindu, Christian, and Iranian iconography. Buddha is depicted within the Vesica Piscis, and Christ appears in Gothic churches within this symbol. The inverse of the Vesica Piscis, known as the “mandorla” (a form created by overlapping two crescents), is also used in ancient art. In ancient musical treatises, the vibration or resonance of stringed instruments was inspired by the form of the Vesica Piscis.

Visica is the primordial form; the first vibration, or the initial call of creation that precedes absolute zero. The oscillation that gives rise to this form is constructed from a round-trip vibration between the threads of the cosmos. With the second vibration, abundance emerges; the threads grasp the command, and the mind of the musician enters into action, grasping the curtain. In ancient treatises, the descriptions of Farabi and Abdulqadir Maraqi begin from this point. These cycles are relative to the orbits of moons and celestial bodies, as Rumi put it: “It is the sound of the rotations of the wheel that the creation / play upon it with the tambourine and with the throat.”

Visica resembles the shape of a plant seed. In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the mouth sign is in the form of visica, which is also the specific symbol used to write the name “Ra” in the creator’s role. In ancient paintings and sculptures, both Christ and Buddha are depicted inside the visica.

Humans perceive the crescent moon shape in other natural phenomena as well. On pottery from Shush, we see depictions of goats with exaggerated crescent-shaped horns, illustrating the connection established in human minds between this terrestrial animal and the celestial sky. The goat, known for its unique ability to find sources of water, played a significant role in human life. Even today, shepherds follow the paths of goats to find sweet water sources.

Additionally, in human experience, the ebb and flow of surface waters and the moon were interconnected. Over millennia, humans understood that with the appearance of the full moon, waters that had descended from the sky were drawn back towards their cosmic source. For ancient humans, the moon was seen as the source of cosmic water. This is an example of the construction of symbolic connections and the creation of a chain of concepts that link goats, moon, water, and fertility together.

Domesticating and raising animals was a significant achievement that made human life easier and richer. On the pottery of Shush, images of goats with exaggerated crescent-shaped horns are repeatedly depicted. Sometimes, only the horns of the goat are shown, resembling the crescent moon in the sky. The changing position of the crescent moon in the sky is one of the most important phenomena that prompted humans to measure infinite time. Additionally, the nightly movement of tides and the attraction of Earth’s waters towards the moon create a connection and interdependence between the moon and water. Adding to these, the cycle of feminine fertility, aligned with the moon’s orbit, further ties together a chain for humans during this period: the goat, the moon, water, fertility, and life, depicted on these pottery pieces.

On pottery, we observe many patterns with various types of quadrant divisions. In fact, dividing the world of phenomena into four natural elements has helped humans understand the universe. In motifs of this period, we find conventional forms for depicting wind, earth, fire, and water. Additionally, there is a fifth element represented as a plant form in Iranian myths.

Moreover, sexual union, reproduction, and water were also interconnected. In the ancient rites where power had to derive legitimacy and authority from the cosmos, humans benefited from the connection between the lunar calendar and the birth calendar. 10 During the Hero’s Games ceremony, a sacred ritual took place at a specific time determined by the astronomical alignment with the moon. During this time and in a specific place, a sacred union occurred between a woman and the leaders of tribes to conceive a royal heir. Thus, the newborn was recognized as carrying legitimate power bestowed by the cosmos. 11

Thus, ancient humans by weaving and discovering connections between cosmic phenomena and their lived experiences, grasped time, imparted ritualistic significance to it, and imbued it with measurable qualities. From this perspective, the history of human scientific thought also traces back to this era; at the boundary between the cosmic age and the mythic age emerges the separation of human consciousness into scientific awareness. Humanity endeavors to understand. The concept of time is an abstract notion.

Merely the repetition and sequence of days and nights do not transform time into a measurable phenomenon in the human mind; rather, it is this boundary-setting of time that brings it into a form that has a before and an after.

The beginning of mathematics is intertwined with human understanding of time. As mentioned, counting began with the discovery of the mystery of the reproductive cycle in women aligned with celestial coordinates. Similarly, initial calculations revolved around the regulation of fertility rites and sacred unions with the ebb and flow of waters towards the sky.

One of the most significant advances in mathematics was the invention of zero and the decimal counting system. With the concept of zero, the possibility of infinite negatives also emerged. The Greek-Latin numeral system, known as “chōbūkē,” did not have a zero. 12 This absence meant that numbers only increased without a direction towards negative values. Another interpretation suggests that the Greek worldview tended towards expansion and abundance, overlooking the contractive aspect.

In this intellectual framework, a “line” is seen as the result of the multiplication and repetition of a point. It’s known that in ancient Greece, geometry predominated over mathematics. Geometry involves the measurement and calculation of lengths and areas, shaping the world based on the measurability of lines, surfaces, and volumes. Conversely, a point lacks this geometric characteristic.

In the cultural history of humanity, the concept of “particle/point/one” emerges in human awareness. The notion of the particle frequently appears in sacred texts as “that which reaches abundance.” The stage preceding abundance is nameless and formless; it is non-named. What makes non-named into named, brings existence into being, is this expansive aspect that is relative to manifestation.

In Indian and Iranian mathematics, a “line” extends from a point. These two definitions highlight an important distinction. Indeed, the origin of the number zero lies where a different cosmology unfolds in defining the stages of existence.

Geometry of the soul

The sacred place, the temple of the soul, is the historical origin of humanity. Naturally civilized, humans concentrate their social aspect in a centralized location. As mentioned, the tribal priest’s tent was a sacred place at the center of tribal settlement, around which the community gathered. The circle is the oldest form of human settlement, still present in the patterns of primitive tribes. Some animals that live in groups also form organic circular formations for protection and cohesion.

At the end of the cosmic era, as mentioned, massive stone structures were built as local observatories of the sky in various regions of the world, perhaps among the oldest sacred architectures that remain. The plan of all these structures is circular. One can imagine that humans derived this shape from nature, observing the circular movement of water around a surface eddy, the swirling of wind in the desert, the full moon, the seed of plants, the growth of plant stems, or the movement of birds and fish, and then abstracted it into the form of a complete circle.

The circle has a central point around which its rotation occurs, creating a simple and directionless form. In ancient sciences, the circle, or equivalently the point, symbolizes the essence of unity and the principle of oneness, which humanity has yet to fully comprehend. The circle possesses infinite axes of symmetry. In a sense, it lacks fixed properties and revolves infinitely relative to its center. Therefore, it has no coordinates and is immeasurable in size.

By placing a square within a circle or vice versa, the circle becomes directional. The square symbolizes the world of multiplicity and manifestness. The contrast between these two is expressed in mythology as the opposition between the Apollonian and Dionysian worlds; the difference lies between the unified world and the world of multiplicities.

In the course of human awareness, from a certain point onward, all sacred plans transform from circles to squares. This period corresponds to the growth of the concept of coordinates in human awareness. Just as there is a relationship between the square and the circle, there is dominion between the point and the chelipa.

In explaining the visibility of the geometry of the soul, the form of the cross or chelipa is not the result of the intersection of two broken lines, but rather a center that has acquired directionality, or a point that has expanded in four directions. Chelipa is the manifestation of the coordinates of unity. Many treatises have been written about it in the science of sacred geometry (Sacred Glometry).

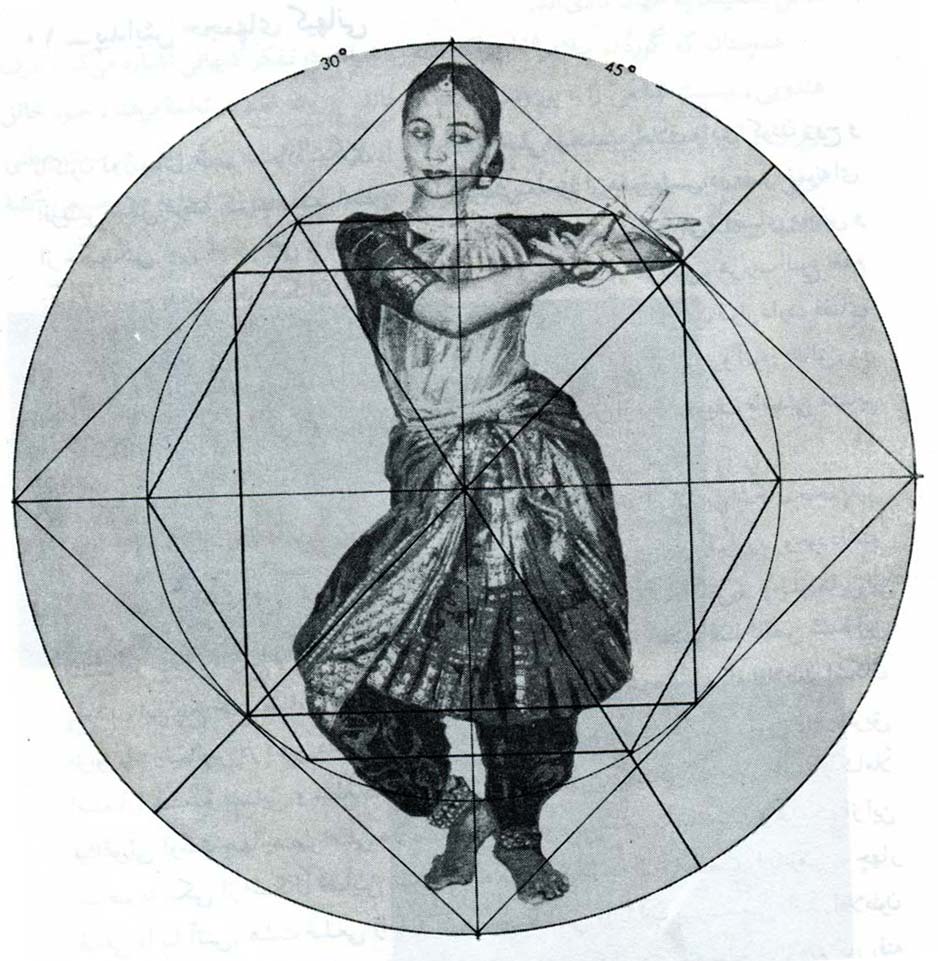

Reaching the absolute square through the drawing of circle arcs has been possible. On the other hand, measuring the area of a circle has been a complex and important puzzle. Efforts were made to derive the formula for measuring the area of a circle by equating it with a hypothetical square. 13 The key to directly discovering the area of a circle lies in discovering the number pi (π), an infinitely decimal number. In sacred geometry, the circle and the square constantly transform into each other, a process known as “squaring the circle”. The significance of this subject in cultural history is such that we find symbols of squaring in all manifestations of human spirit (which we now recognize as art). The Greeks based their interpretation of beauty and proportion of the human form on this principle; the navel is placed at the center of the circle, and the line of the spine intersects with the lines of the shoulders to form a chelipa.

In Persian poetry, we repeatedly encounter themes that refer to the circle, point, and chelipa. In the words of Shah Da’i Shirazi: “You are a point, the universe is a circle / The point is hidden, the circle is manifest.”

As mentioned, in architecture, the spirit finds its coordinates. The product of spiritual fragmentation during this era is the transformation of circular plans into square forms within subsequent sacred spaces and communal centers. We witness this transformation in ziggurats, pyramids, the tomb of Cyrus, the Kaaba, and others. Then, the initial simple squaring off within sacred plans expands in complexity, and the manner of this expansion relates to the architect’s interpretation of the concept of time. This interpretation alters the sacredness of space.

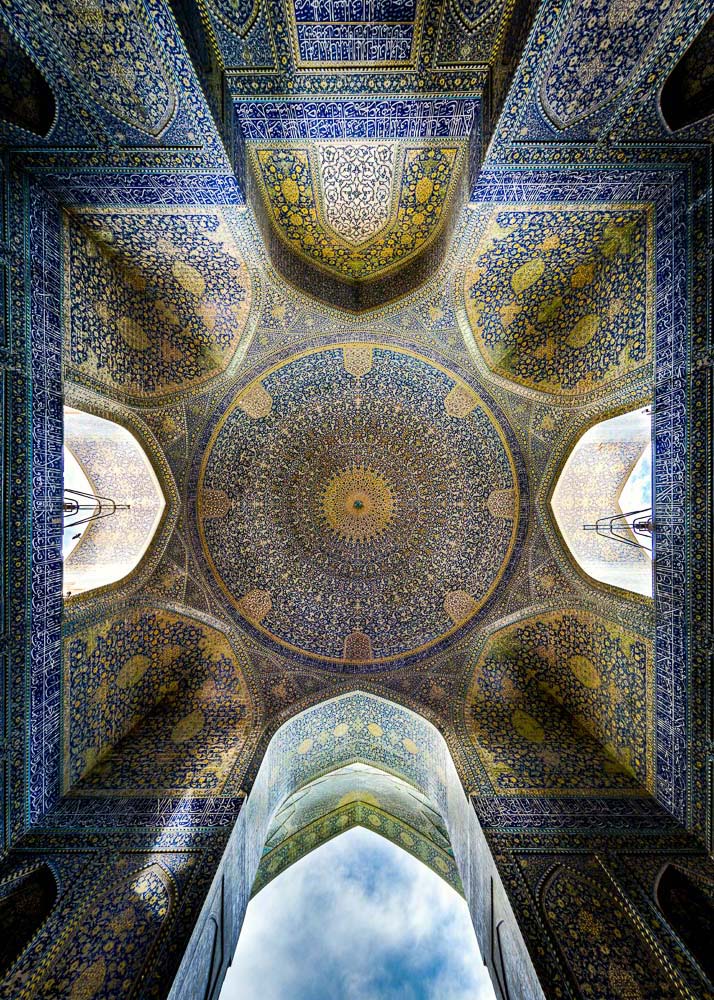

Thus, we see how, from a certain point onward, squaring off has created different forms in various cultures. The spatial layout of Roman Catholic churches differs from Hindu temples or Iranian fire temples and mosques. For example, entering Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque involves spiraling around; architecture leads us towards the building under the dome and the center of the square, where light apertures and patterns drawing the gaze upwards bring us back to the domed structure. Essentially, in all Iranian architectural works, the square circles back to the circle. Beneath the dome, as we move away from the central focal point, intricate and obscure patterns gradually become clear, and approaching the lower square creates discernible motifs that return us to our dwellings.

This beautiful poem by the Persian poet, عراقی (Irāqi), explores mystical themes using the metaphor of a circle and a point to convey profound spiritual insights. Here is the translation:

Let love reveal itself to you, manifesting openly, Reflecting in the mirror of the world.

This mirror shows the face of truth, Every moment freely revealing itself to you.

Imagine the world as a circle, Every point within it reflects back.

This circle has no more points, Yet it appears in such a way.

Turn the point into a spark of fire, So it animates into a moving circle.

This point, through its speed of motion, Manifests a hundred circles at every moment.

This point testifies to you, in both seen and unseen, Manifesting in apparent and hidden forms.

That point shows you absolute perfection, In both this and that form.

The perpetual motion of this point, Makes it appear still in one place.

Every moment, the perfection of existence, Manifests in the guise of imperfection.

Let me describe what this point is, Even though it may seem unknown to you.

Know that this point is the shadow of light, And that light reveals its essence.

That light is the heart of our Prophet, Now let the truth reveal itself to you.

That limitless ocean surrounds, And that eternal light illuminates.

In all Iranian architectural works, there exists a continuous oscillation between square and circle. Under the dome’s role, as it moves away from the central focal point, intricate and initially obscure patterns gradually become clearer. As the base of the dome nears the square below, these motifs become discernible and return to earthly dwelling.

Another manifestation of the mandala is found in Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies, where continuous creation and destruction of the mandala symbolize the cycle of existence. The Dalai Lama places the initial point using a specific color.

The color itself signifies the apparent aspect of the world. Then, monks create a large mandala around this initial point using various colors in relation to it. Finally, when the mandala reaches perfection, the monks dissolve and destroy it by mixing the colors together. In other words, in this form of awareness, the dwelling transforms into samsara (the cosmic illusion).

Tibetan Buddhists engage in rituals involving the continuous creation of mandalas that explain the history of existence. The Dalai Lama begins by placing the initial point using a specific color. The color itself represents the aspect of the world’s apparent reality. Subsequently, monks create a large mandala around this initial point using colorful sands in proportion to it. Finally, when the mandala reaches perfection, they mix the colors together, dissolving and destroying it. In other words, in this form of awareness, earthly dwellings transform into illusion or samsara.

This process symbolizes impermanence and the transient nature of existence, emphasizing the Buddhist principle of detachment and the cyclical nature of life.

Tibetan Monks from the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery complete a Chenrezig Sand Mandala in Salisbury, England.

In music and dance, this manifestation is also evident. The rhythmic movements of the human body, as mentioned, symbolize the cosmic cycle. The earliest forms of dance rituals involved circular movements around a fixed point (as seen clearly in Sufi dancing). In more complex dances, movements in various directions relative to the central axis of the body depict a coordinate system. Each of these body postures and directions in ritual dances serves as a “mudra.” 14 The word “mudra” means gesture or symbol. Each mudra signifies a letter, and together they form words, creating meaning.

For example, in Buddha statues, hand gestures or the triadic postures of standing, sitting, and reclining are interpreted as meaningful mudras. In all these postures, the axis of symmetry holds significant importance. Similarly, in Greek sculptures, gestures and mudras are sculpted in relation to the axis of body balance. Changes in symmetrical body postures indicate a transformation in cultural awareness. From a certain point onward, Greek sculpture depicts a slight rotation of the chest axis relative to the hips, creating a sense of movement. This contrasts with Egyptian art where statues are static, symmetrical, and stationary, indicating a different stage of cultural evolution.

The proportions of the pharaoh’s body, whether in seated or standing posture, are derived from the square, but there is no indication of movement in him. This demonstrates that the pharaoh is absolute and timeless, transcending both past and future.

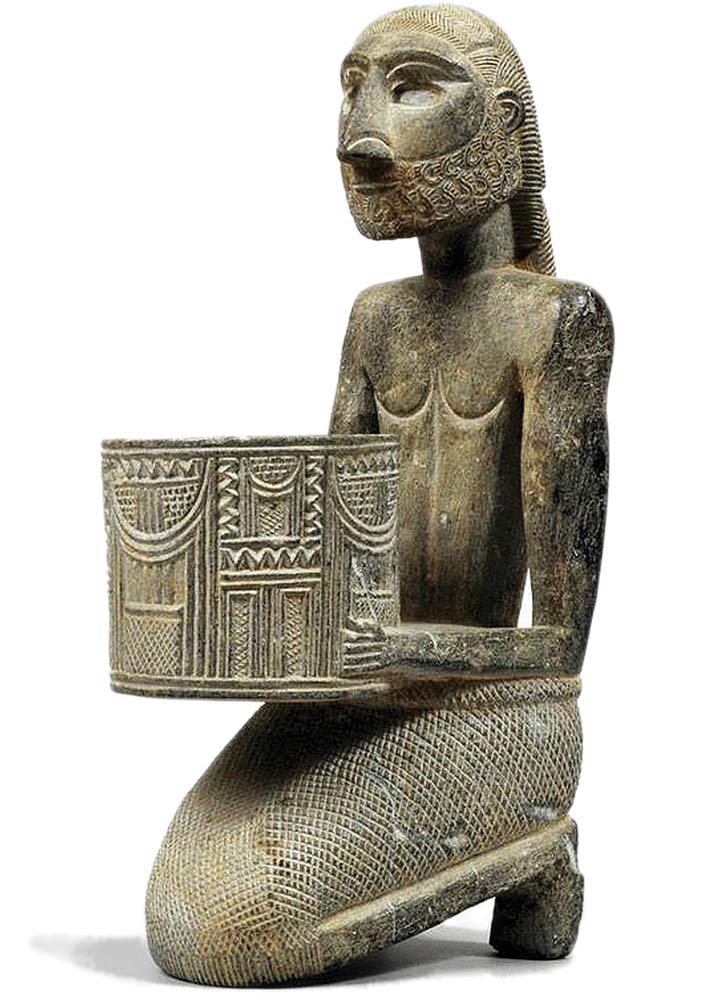

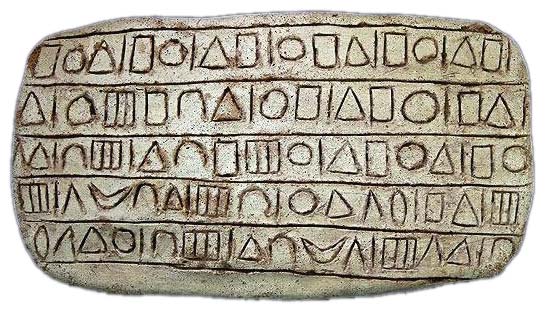

Mudras can indeed be considered the first alphabet of the spirit, and perhaps they can be viewed as the “ABCs” in a broader sense. In the design of script lines as well, we often encounter this system of squares. One of the earliest examples of writing tablets found in the world was discovered in the Konar Sandal region of Jiroft. In this script, the basis of squares is used to design symbols, with three primary forms: square, triangle, and circle, and variations in their positions convey letters (and meanings of words).

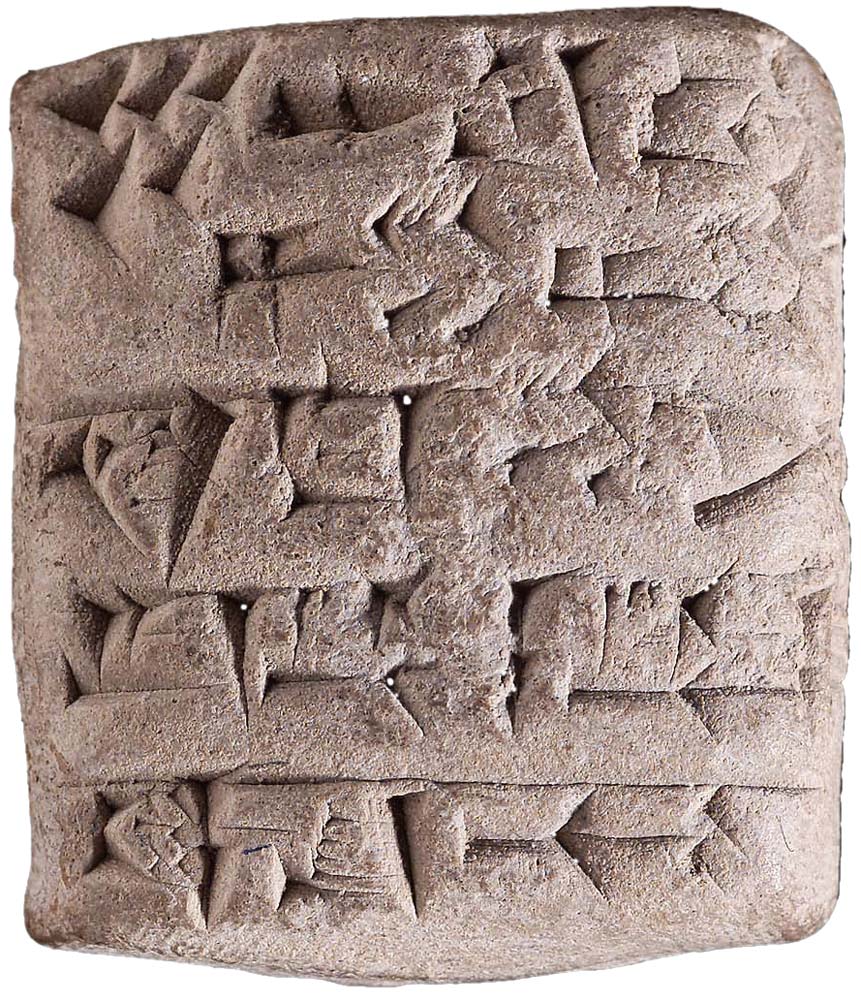

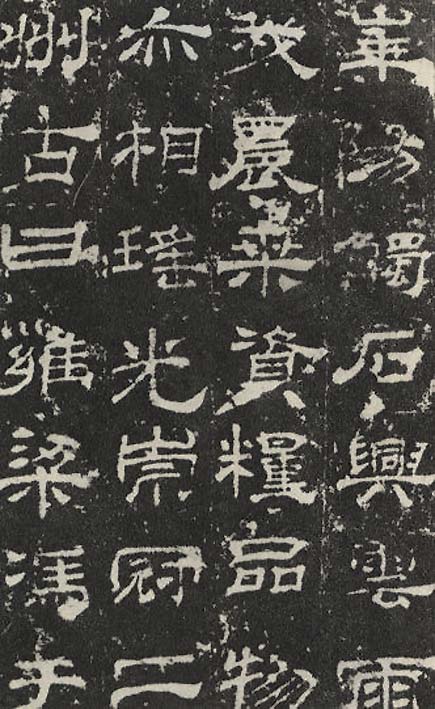

Chinese calligraphy also follows a squared design; the pattern of all characters (kanji) is square-shaped, which allows for a great variety within it. The formal structure of Hebrew letters is also square-shaped. Ancient Persian cuneiform script starts with a point that extends in a direction, with its fundamental base being square.

Ibn Muqla also established the principles of segmented script lines based on this square principle. In his treatise, he explains how he derived the principles of these lines from the element of squares.15

The concept of centrality is crucial in understanding human awareness and perception. The inception of astronomical knowledge involves measuring changes in the cosmos relative to our position, which is only possible when humans establish a reference point for themselves. This idea becomes more complexly crystallized in subsequent eras within urban contexts. Plato, as the initiator of philosophy, constructs his intellectual framework around the concept of the “polis” (city-state) and describes it through his philosophical system, which incorporates a mythic-cosmic network preceding himself. His interpretation of the world is not merely about the ideal relationship between heaven and earth but extends into civic thought.

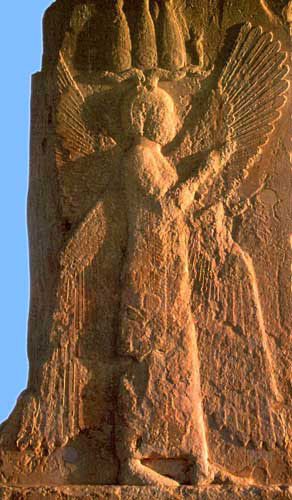

But why is the concept of centrality so important that cities are shaped around it? What is Persepolis? What is the Acropolis? What do these monuments explain? In Iranian thought, terms like “Raynakh” and “Khushthariyya” refer to urban administration and governance under the Fourfold Wisdom. In the story of Zal and Simorgh, which marks the beginning of the concept of Pahlavan (hero), Simorgh bestows its four “wings” (par) upon Zal at the moment of separation. In Pārsehgar, we see the image of the wise ruler with four wings carved behind him. Within the vessel of the existing form of “wings and feathers” which has been created in the context of the traditions of composite imagery between Mesopotamia and Jiroft, gradually in this cultural area, the embryo is imbued with different meanings. Later, we will discuss the concepts of wisdom and the Fourfold Wisdom in Iran.

In the narrative of Pahlavan Farhmand, Simurgh bestows its four wings (farr) upon him at the moment of separation from Zal. In Parsi Gard, we see the depiction of Farhmand’s rulership with four wings engraved behind him. Within the pre-existing forms of Mesopotamian imagery, new meanings gradually emerge.

In very ancient shamanic rituals, the shaman would establish a temple not in a physical sense, as it was later constructed, but in a mental one. He would hold a sacred staff and, while reciting incantations, point to the four cardinal directions, thereby creating his temple. Early human tribes, who seem to have originated near Ethiopia, migrated across the world in search of food due to climatic changes. Over time, these scattered groups each began to recognize a place of origin for themselves, leading to the emergence of new meanings such as “return,” “dwelling,” and “journey.”

These meanings, although in newer forms, remain powerful to this day. It seems that the desire to return to one’s birthplace has become a deeply ingrained aspect of human nature. The concept of returning to the origin, in each cycle of an annual calendar, is vividly expressed in religious rituals among Hindus with the Ganges River, or among Muslims during the Hajj pilgrimage. 16

Many contemporary forms of migration can also be interpreted based on ancient migration myths, each of which establishes a specific relationship with the concept of the origin. This can manifest as a return to the origin, for instance, in the modern form of migrating to the West, aligning with the idea of the origin of the times. It can also take the form of the hero’s journey in discovering the world, such as in the myth of Gilgamesh; or following the Robinson Crusoe model, with the fear and thrill of losing the origin and immersing oneself in the heart of primitiveness; or like Faust, with the idea of mastering the world.

In primitive forms of determining the center, which initially was a sacred place and the focal point of power, natural factors were considered—specifically, the relationship between earth and sky. This could be a sacred spring emerging from the ground, a place where water bifurcates (like the Notre Dame Cathedral), a mountaintop (such as the Fortress of the Girl or the Acropolis), a location with ancient trees, or where winds swirl. Over time, and in relation to the ruptures that occur in the spirit of every human society, the center of the city may be relocated or even become multiple, but its necessity for defining a city is undeniable. The city takes shape relative to this center, and various aspects of consciousness are revealed within it. Any change in the location of the center indicates a change in awareness.

Since the concept of the center has a civic dimension and the notion of power revolves around it, the layout of cities varies across different cultures. Depending on the characteristics and power structures of cultures, cities may have one or several centers. In Iranian cities, a fourfold system was predominant; cities were circular, and sacred places were square. Later, Islamic cities were also built based on this pattern. In European cities, due to the triadic nature of their culture, cities have three centers.

In modern cities, the function of the center has not changed, but its location has shifted due to the evolving relationship between subject and object and the concept of power. At one time, the cathedral was the center of power, legitimacy, and knowledge. Later, academies and universities, courthouses or legislative buildings, and today, stock exchanges or fashion centers have become the new focal points of modern cities.

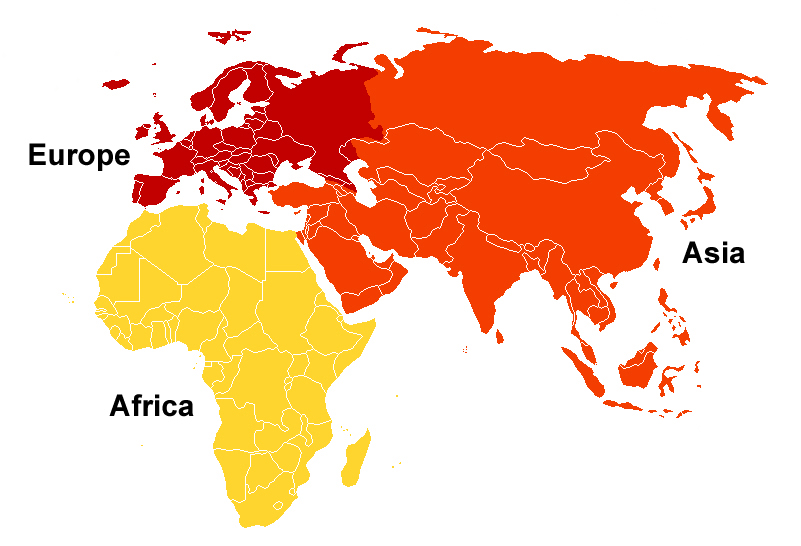

In determining the origin and its general acceptance, the role of power centers is evident. In the Iranian world, the observatory of Zabol was recognized as the origin, and based on this, the region was called Nimrouz. There is evidence suggesting that the Iranians, based on surveying the boundaries of the ancient world from the China Sea to the Canary Islands in West Africa, identified a place right in the middle of it as the axis of Nimrouz. Other origins also existed in different parts of the world, according to the knowledge of the people. Since today’s world is under the dominance of Anglo-Saxon power, Greenwich has been accepted as the prime meridian for determining time and measuring location since 1884. The Greenwich meridian connects Buckingham Palace, the Parliament building, the clock tower, and the stock exchange building, all situated relative to the Thames River.

What is certain is that every power wishes to define the center within its own territory. Significant historical events have sometimes occurred in connection with changing the prime meridian. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity happened in the midst of a war with Iran, effectively shifting the focal point of the predominantly Mithraic Roman army from Lake Hamun in Sistan, within enemy territory, back to Jerusalem in Roman territory. The Crusades’ excuse for several centuries was to capture this focal point. The Catholics, by transferring what they called the remains of Saint Peter to Rome and quoting a saying of Christ that Peter would be the rock upon which his church would be built 17 , moved this center from Jerusalem to the heart of Europe and the Vatican. Similarly, the change of the Muslim Qibla from Al-Aqsa Mosque to Mecca during the time of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is considered a significant historical event for Muslims.

The prime meridian has shifted multiple times and has often been recognized differently by various societies. One of the oldest of these meridians is the Nimrouz axis, located precisely in the middle of the Eastern Hemisphere. The selection of this point as a reference for geographical calculations in the Iranian world was based on precise scientific foundations. The distance from this region to the Kuril Islands in the Pacific Ocean (the easternmost inhabited area) is the same as the distance to the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean (the westernmost inhabited area), both being 90 degrees. In other words, when the sun is at its zenith in Sistan, it is setting at the easternmost edge of the ancient world and rising at the farthest western point. This means that when it is noon or Nimrouz in Sistan, the entire known world of the ancient times is in daylight.

The very naming of this region reflects an awareness of its significance. Various texts also reference this area, the oldest being the Mihir Yasht in the Avesta. In later periods, various texts, including “The History of Sistan” and “Ehyā ol-Molouk,” mention the significance of this point and its observatory. 18

The role of the center remains evident in today’s world. Whoever holds sway over an era explains everything in relation to their centrality. This centrality in awareness empowers the observation of the world. Conversely, the concept of power in any civilization diminishes when it loses its coordinates.

Burial as coordinates

Death is the most real truth, or the most real reality of human life. Humanity’s endeavor to attain eternal life, and then the acceptance of death in the tale of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest myths of human spirit, is visualized. Perhaps from the earliest and most fundamental questions of humanity, inquiries about the essence of existence and spirit have been raised, including where this existence goes; in other words, the question of what it means to be human.

The oldest surviving ancient artifacts are often related to death. Rituals involving death (such as burial and cremation) emerged during a period when humans began to understand their separation from nature and experienced this profound rupture. Death likely held the meaning of returning to a necessary and simple world for humans in ancient times. Thus, fundamentally, death rituals have bridged the past and future. The deceased were interred in such a way that they could easily journey to the future, or the world of destiny.

Cemeteries are important sources that enable the understanding of the past. The evolution of human awareness in ancient times can be observed through their attention to the concept of orientation and “direction” in burial rites, and in the remains of ancient cemeteries that can be revisited. Bodies in every civilization have typically been buried facing towards a source or center. In Egypt, mummies were placed in alignment with the cosmic map, in connection with the sun and stars. In some Native American tribes, bodies were coated with gypsum and stood upright facing the direction of the sunrise, preserved in that stance.

Cemeteries also provide insights into the evolution of understanding the concept of time among different cultures. In Egypt, one of the oldest civilizations where the meaning of power in society was manifest, we see a mechanism of societal continuity linked to the theme of death in their burial practices. The pyramids are tombs intended to grant eternal life to the pharaoh, in whom the essence of power was embodied, and to guide him into the afterlife.

Remnants found in ancient cemeteries illustrate humanity’s response in each era to the question of the otherworldly. These rituals have all emerged as responses to the relationship between the psyche and existence itself. By conducting funeral ceremonies, humans provide a definition of the deceased person or, more precisely, an outlook on their future. In the following periods of history, we observe how human awareness gradually dissects the themes of body, mind, soul, and intellect.

Postnotes:

1. walde, pokorny; Vergl. Worterbuch d. Indo-Germ. Sprachen; II, P241

2. Gershevitch, Ilya; The Avestan Hymn to Mithra; University of Cambridge Oriental Publications, 1959, P28.

3. In some civilizations, such as in Hinduism, remnants of cosmic epochs persist in the belief in the antiquity of humanity and the inseparability of humans from nature.

- Holderlin describes this ancient meaning in poetry as follows: “Apollo threw me into existence like an arrow.” Or in Hafez’s words: “I have drunk the arrow of the sky, give me wine to be intoxicated / I will untie the knot of Sagittarius around my waist.”

In these examples, the artist has composed their perception of the world not out of historical awareness but by relying on their poetic essence.

- Typically, peoples who face defeat or injustice return to their archetypes and myths for their reconstruction: Hence, the role of Ararat has become more pronounced for Armenians.

- Turfan documents indicate that the twelve-year cosmic cycle likely has partisan roots, emphasizing the role of animals.

- The gradual elimination of masculine and feminine pronouns in some historical languages like Persian is a separate issue that relates to Iranian legal thought. Articles of dual gender still remain in some Iranian languages like Wakhi and Sangsari, apart from the Avestan language.

- vesica

- For further reading, refer to: Robert Loller, “Sacred Geometry: Philosophy and Exercise,” translated by Haydeh Mo’ayeri, Tehran: 1368, Cultural Studies and Research Institute.

- The fountain symbolizes the material manifestation of water’s leap. The sign of this leap is also seen in the prayer of ejaculation among Christians. Fountains in Gothic churches are features of femininity and are a symbol of fertility rites. In agricultural societies, the concept of planting, harvesting, and consequently the concepts of fertility, reproduction, and lactation, and fundamentally life, are important. We find examples of this in myths such as Anahita, Venus, or the Sacred Mother in various societies. In Iranian thought, the right of ownership of water belonged to women, which has its roots in this ancient belief. Among the oldest surviving temples are the Moon temples, which can be explained with the discussions mentioned.

- This connection is also seen in myths where a newborn is immersed in water. Thus, the child is transferred from the cosmic water ceremony to earthly abodes. Numerous stories of kings and dignitaries from Egypt and Mesopotamia can be found that refer to this ancient ritual in its complete form or remnants of it in public beliefs. In an inscription of the Assyrian king, we read that he speaks only of his mother’s lineage and then says they threw me into the Tigris.

In the inscription of Shapur, the Shahanshah of Iran, it is stated: “I am Shapur, the son of Ardashir, descended from God.” He introduces himself in the likeness of a divine figure, which grants him power from the ancient time. Power in the church is also eternal and eternal. Because with the grace of the Holy Spirit from the Father to the Son, and from Christ or the Son to the apostles, it continues to the kingdom of heaven.

- The introduction of the number zero into European knowledge returns to Fibonacci in the 13th century AD.

- The problem of squaring in ancient geometry was finding a square whose area is equal to the assumed area of a circle. And this is one of the three famous geometrical problems “trisection, definition, square” in the ancient world. The impossibility of this problem has been proven today.

- “Modra” is an Avestan word that has traveled from Sanskrit to languages of the Far East, meaning Indian and Chinese.

- Quoting from Raha al-Sudur Ibn Rawandi. His treatise is mentioned in the introduction of Qazi Ibn Khalkan.

- The native Australian walkabout is a survival of this ancient experience. The direction of movement is towards sacred hills and the journey lasts a year, although the counting of years among these natives differs from ours. This ritual is held as a repetition of the eternal memory of the rupture from the source, which is held as going to the source and returning. The depiction of footprints in new Asian, Oceanic, and Australian arts refers to this ancient ritual.

- “You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church.” Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 16, Verse 18.

- Iraj Afshar; Sistan Observatory; Congress of Geographers of the Islamic World. Reza Moradi Ghiyasi Abadi; Nimrouz Observatory.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.