“The pulse of contemporary art is fortunately beating at the same rhythm in Iran today as it is in developed countries… We now have contemporary and avant-garde artists who are busy creating new media, such as digital art, just like what is being done from a technical perspective in other places such as London and New York.”

“With the overture experienced in recent years, our artists have been able to be present in the international scene and, ten years on, Iranian art has become the most contemporary form of art in the entire region. In international arenas where the contemporary art of the Middle East is discussed, Iranians are often among the most contemporary.”

Alireza Sami Azar

Our experience in the new era has been one of backwardness; there is a kind of awareness that tells us that time ‘here’ is behind time ‘there’. This sense of slumber transforms any search for a solution into a desperate struggle to make up for the lag we experience. Since the 1950s, when this distance became ever more palpable, it seems as if we have reached the conclusion that this lag cannot be compensated at the prior pace. In the 1960s, and in his first speech as the Dean of the University of Fine Arts, Mohammad Amin Fendereski clearly expresses the anxiety that stems from this confrontation between fast and slow: “From this day forward, we shall dismount the camel and take flight with the Concorde.”

Therefore, a new era has begun in which our awareness of the times ‘there’ is constantly “updating” visual arts ‘here’, albeit with a delay of at least thirty years which seems ever so irreversible, thus deluding us to think that “the pulse of art here beats to the rhythm there”; however, after some decades, this seems to be far from the reality. Forget the Concorde, not even the internet has been able to synchronize the creation of art ‘there’ and ‘here’. What is in fact moving closer together is the how quickly “tools” of artistic creation are utilized. These “tools” can be cubism, surrealism, abstract or new art. We are not the creators of such tools; we merely compete to buy and utilize them at the fastest pace possible. In past decades, this struggle to synchronize or contemporize ourselves with the West has maybe been the most important depiction of the concept of “time” in the minds of our modernists: “another’s today as our future”, or the hope that one day our future will resemble their ‘today’. Every time we felt we could catch up by taking shortcuts, we found them to be even more distant and less accessible. What resulted from modernism was the unfortunate awareness that we (with this language and geography) do not have the ability to contemplate and envisage the new world. Admission of this defeat can most clearly be seen in what Morad Farhadpoor famously states in the preface to the book ‘Depressed Mind’: “In the contemporary era, which began with the Constitutional Revolution and will probably come to an end in a not too distant future, translation, in the widest sense of the word, is our sole true form of thought.” Considering the fact that these efforts toward synchronization have not come to fruition in a collective manner, and perhaps with no hope for their realization in sight, Iranians have turned to a more individual solution: immigration. This immigration cannot really be explained with the common theories of the search for prosperity or security; it can rather be interpreted as a tendency to immigrate in time, to reach a geography in which the pulse of time beats.

In the same preface, Morad Farhadpoor goes on to say: “It can undoubtedly be said that there is no idea, thought, or theory in the articles of this book that has not already been stated more beautifully elsewhere.” If we do not admit to this with regard to all forms of theoretical thought, it is undeniably true at least when it comes to the works of our artists. The issue is that, with regard to art, accepting the fact that an artwork has been previously created elsewhere and in a better manner negates the ‘artisticness’ of that piece. The fact that we have basically not had any true art in the past seventy years is very difficult to swallow, especially for a people who have considered themselves to be possessors of art for centuries. In these circumstances, the solution was to accept and justify the status quo, to say that it is true that we are not the innovators and creators of new artistic tools and theories, but what we do produce are not identical copies either; we utilize the artistic apparatus of others to state our own thoughts and recount our own story. This is a misunderstanding from which a thinker such as Morad Farhadpoor is exempt, especially when admitting that what he says is nothing new, but merely a form of contemplation through translation. Even more intellectual than philosophers are engineers and scholars of technical and experimental sciences; they know well the astronomical distance between technology ‘here’ and ‘there’. Since the construction of Veresk Bridge, our engineers have been well aware of the undeniable gap that exists between rail transport technology here compared to the most advanced technologies of the day; but our artists continue to suffer from the delusion that they are able to simply leap from the platform of our history toward the future. This image of time bears with itself three major problems that render the emergence of any new form of art within the paradigm of modernism in Iran practically impossible:

Modernist Iranian artists see their starting point in another geography and history. In an interview with Tandis magazine for their 292nd issue, Alireza Sami Azar states: “Iranian art has been transformed into the most contemporary art in the entire region.” This sentence might contain a certain naivety or envy with regard to becoming contemporary, but hidden beneath is a kind of perception and depiction of the concept of art and time whose extent and longevity go beyond this single remark. The use of a superlative for the concept of being contemporary means that the speaker has accepted a form of art in another place and time as the starting point of contemporariness and considers all other art to be relative to that point, either nearer or farther. This is the same image with which modernist artists have assessed their era and works in the past seventy years. From the 1940s on, Iran’s modernist artists have gained a sort of awareness with regard to the concept of “era” or “times”, meaning that art must be in relation to its “time” and that a change in the times must transform art; however, what Iranian modernists have overlooked is the reality that time is a concept dependent on geography. Human awareness is bound by history, and history finds meaning within the realm of geography. Ignorance with regard to the reality that time is not defined in London or Paris or New York renders meaningless the efforts of these decades.

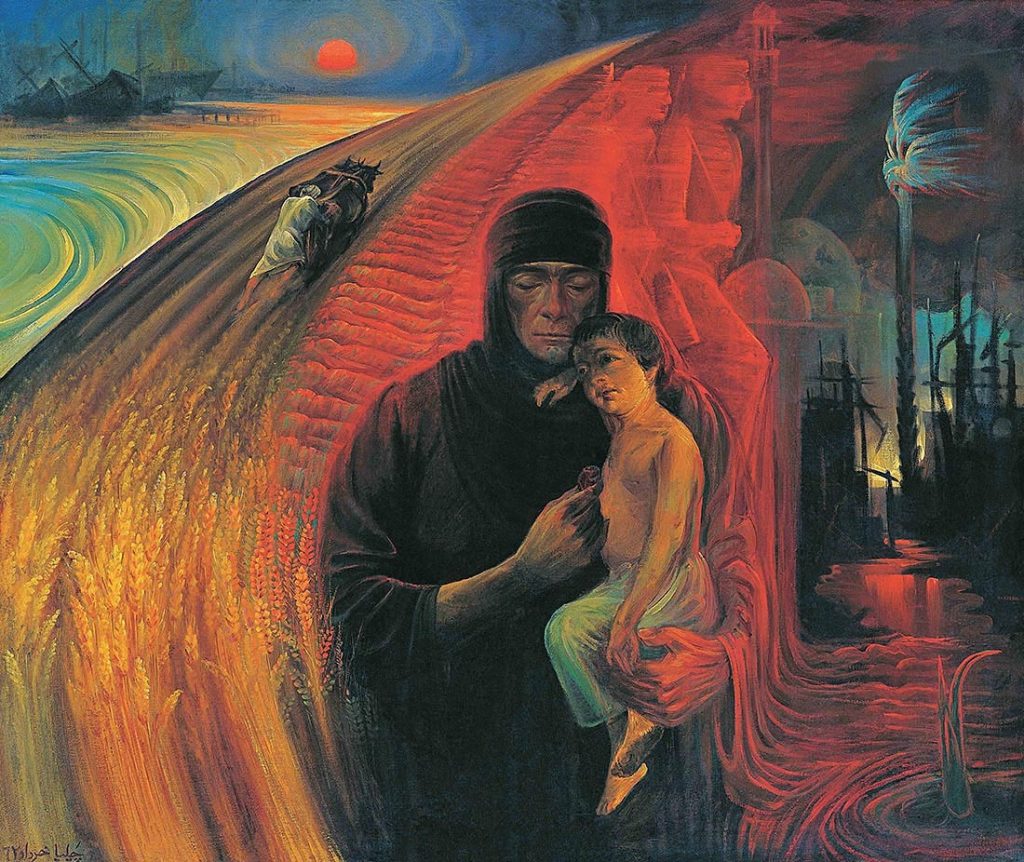

That which is happening in innovative centers of the world is the designation of eras. Whoever names the era eventually comes to own it and whoever doesn’t traverses timelessness. In their early years, Iran’s modernist artists found a simple solution for this problem: they discovered apparent similarities between modern Western art and Iranian symbolism and motifs and, by combining these two non-synchronous artistic forms, they created a mixture that could fill and concretize the deep rift between our time and theirs. However, this rift once again broke open in 1979.

What we accept as the origin of time with regard to the concept of contemporariness is not a constant and static phenomenon. Not only are the times constantly changing in the origin itself, but a new definition and understanding of the past is also being formed every day. In other words, the past is also evolving in this origin of contemporariness; new definitions and critiques of the phenomenon of modernism are being presented every day and art history is being written anew with novel approaches. Therefore, in such a system, our modernists will not only never reach where ‘others’ are now, but they will also consistently fall even further behind. With the rupture of our ties with the West for a span of two decades following the Islamic Revolution, our artists sought a kind of rethinking of their artistic achievements and the question everyone asked was how we could become modern, neglecting the fact that the image of art had totally changed during that time. As soon as the first overtures occurred, efforts toward synchronization were once again undertaken, but this time around everyone aimed to be postmodern.

Modernists have accepted the verdict that art must express the spirit of its time. A deadly turn is hidden within this famous seemingly simple sentence. From this misplaced interpretation of the spirit of time, artists have tried to pour symbols and themes from the conscious mind of history or their life experiences into a form they have taken from another place’s “now”. Many of our artists today utilize the sociopolitical events, problems, and contradictions they experience as the subjects or themes of their artistic works. Since the 1990s, artworks have been filled with references, messages, slogans and explicit sociopolitical signs. Simple items such as hijab, the Green Movement, freedom of expression, air pollution, censorship, immigration, and feminism which have been extracted from the “news” have become icons that possess signs of their time; however, they do not represent their era and for this reason they have an expiry date. As soon as the issue fades from public opinion, so does the artwork itself.

With a delicate modification though, the meaning of the sentence totally transforms: “An art work ‘is’ the expression of the spirit of its time”. This means that if a work is truly ‘art’, its era takes its name from the art work; in other words, it is art that precedes and thus names history. A work must first be accepted as art – a symbolic form which carries collective meaning – and then it is through this artwork that we understand in what era we are living. Artistic creation penetrates the deeper subconscious levels of its era with the help of the artist’s creative sensitivities rather than with a generally intellectual ideological self-awareness. An artwork is the semantic embodiment of its time, thus naming the era in which it is born. It is art that can move past the everyday conditioned level of history and reach its lower subconscious levels. By doing so, it can denominate its era more influentially than many philosophical theories and scientific calculations.

What builds the foundation of our future is the fruit of our confrontation with the ‘here’ and ‘now’ within a symbolic historical or linguistic system through which we contemplate. This language can be oral or written, visual, architectural or musical, etc. ‘Here’, ‘now’, and said language are all based in the past. This is how the past, present, and future are bound together. Therefore, without fundamental knowledge (fundamental in terms of awareness, language, and culture) in the past, without presence, observation, and experience in the present, and without a symbolic system of visual contemplation, no new image can come to be. Modernist Iranian artists lack all three of these necessary, but not sufficient, conditions. They do not know the cultural institutions of their past, nor do they live in the here and now; instead, they are constantly trying to become the contemporary of others in the future, without a symbolic historical system in which image can be contemplated.

One who can name time can possess it. He is thus contemporary; contemporary not with others but with himself. By naming the times, the historical human (a human who has an understanding of the concept of history and knows that his awareness of history is conditional and limited) changes time into history and hands it over to the past. Defining and forming time anew is not an individual project. New institutions must be established in order to be able to name the times in the new era, and I do not know of any people or nation who managed to create a novel and original image in the new era without building these institutions: the institution of historiography (art history), the institution of museums, and the institution of academies.

Institution of Art History

Not all nations possess language and a historical system of art. Only if the meaning of art has digested changes within itself among a people throughout centuries and survived rifts and ruptures can it be transformed into historical art for which we can write history. If an art remains in its natural state throughout different eras and stays as it has always been (such as with the art of African tribes and others), we cannot refer to it as historical art. Hence, there are very few cultures that possess historical art. Discovering and comprehending the fact that symbolic systems, or languages, are constantly changing, and are therefore historical, is a key point in entering the new world. It is in relation to old definitions that new definitions appear, and this evolution is not just within works of art, but it is realized in symbolic systems or artistic languages, as they are parts of a whole; in other words, the history of art is the history of the development and evolution of languages. If the visual language of a people does not possess the ability to observe and contemplate its ‘here and now’, it can have no new art, and consequently no new art history. The meaning of art, or in other words that of symbolic visual systems, has changed several times in Iran and reached immense complexity and heights in some periods, the likes of which can rarely be found elsewhere. This linguistic development can be followed in every facet of Iranian culture, from architecture to literature, to music and visual arts, and its history can be written – even though we have not done so thus far. However, naming Iran’s art history is not possible unless we thoroughly understand this concept through its specific tools. Creation of these tools does not mean a return to our origins, nor does it mean “what we ourselves once had”; it does not mean opposition to the West, nor does it mean reinventing the wheel; what it signifies is establishing anew, a structure which can only be built on pillars of a theory on the notion of Iran. Without a fundamental theory and history, based on the definition Seyyed Javad Tabatabaei gives of this notion, no such renaissance is possible.

We have had many artists in these seventy years. Each has creatively experimented and created works to the best of their talents and abilities; however, they have all done so in a system different than their own. This is why their works are nothing new, nor do they possess the ability to develop and change the system of visual creation. In such a paradigm, the artist will always remain a pupil, lagging behind the master. And this is the reason why we cannot write a new history of art, for we have not experienced the development of a new artistic language. What has been written as the history of contemporary Iranian art are merely incomplete and delusional encyclopedias which are not cognizant of the fact that they are not history, and for this reason the authors have no choice but to dedicate a part of their book to any and all living and deceased artists, in order to prevent any form of protest on their part. In these conditions, the only thing we can hope to write are encyclopedias of art (archives) which can maybe one day become a tool for writing history.

Institution of Museums

The creation of museums is linked to the perspective we have toward time. On one hand, our intellectual artist lives in the present ‘there’, seeking to make up for the lag we experience, and his main concern is not the formation of museums and history; on the other hand, following the Islamic Revolution, a type of verbal ideological history gained hegemonic power which held animosity towards the new definition of history of which museums were a representation. As in the case of the history of Islam, which was divided into the eras of ignorance and Islam, in this verbal ideological history as well, our history was divided into pre-revolution and post-revolution periods, with governmental organizations taking the revolutionary nation back to the starting point within a mechanism of ‘return to an eternal moment in time’ through semi-rituals (very similar to the ceremonies of Muharram) on calendar observances, such as the Fajr Decade and the start date of the Iran-Iraq War. Within this ideological system, these events must not become part of history and thus a part of the past; they must regularly be summoned in the minds. The ideological art of the first decade of the Revolution was formed on the basis of such an interpretation of history and time, with a permanent link between a moment of the Revolution or the Iran-Iraq War (in the ‘now’) and an eternal moment from the past, such as Ashura. Museums and archives are in fact the polar opposite of such a verbal form of history. Just as “going to hell” was equated to “entering the annals of the museum of history” in conventional official literature in this period, there was a systematic effort to remove any part of the past that did not benefit ideological activity, with the most insignificant budgets allocated to preserving cultural heritage and the historical fabric of cities destroyed and archeological artifacts looted and smuggled abroad with the help of rabid capitalism.

Institution of Academies

Academies are meant to transfer tradition to the next generation. Following the downfall of the old system of visual creation in Iran, the academic system specific to it also deteriorated. At that time, Iran’s first school of new art was established. The School of Fine Arts was an effort to bring the grand tradition of visual creation from the West to Iran; however, with the entry of modernists into the realm of visual arts, facing a flood more rapid than ever before, this effort broke down and was then forgotten. Universities, which strove to teach artistic modernism to students, were themselves suffering from a lack of knowledge and awareness with regard to the phenomenon of modernism. The idea of a return to the past in order to move toward the future was ultimately the most university modernists were able to achieve: the Saqqakhaneh. After the Revolution, universities were divided among two groups, modernists and painters of the Islamic Revolution (whose interpretation of time was previously discussed), and the approach of modernists ultimately prevailed. But modernists are ‘traditionless’ artists; to synchronize themselves with the West, they put aside their flimsy short-term traditions at any moment in search of a new style and method. One moment they would look to be cubists or surrealists or modern abstract painters, the next they would seek postmodernism without having truly become modern yet; and today they all want to be “contemporary”. In this way, there is no collection of experiences, knowledge, art, and tradition that can be transferred to the next generation. Nowadays, the innumerable art universities we have neither possess the slightest ability to understand and transfer Iran’s ancient visual traditions, nor are they able to teach the grand Western tradition of representation that Kamal-ol-Molk strived to learn and teach, nor can they teach the tradition of artistic modernism which several generations struggled to comprehend, a rich collection of which is buried in the Iranian Museum of Contemporary Arts.

Therefore, in the state we are in today, where we neither have museums, nor are we able to preserve our cultural heritage or at least protect them in our own country, nor have we written any art history, nor do we have any academies that can transfer traditions in their current form to the next generation, how do we expect ourselves to possess new art, whether modern or postmodern or contemporary? New institutions are a pre-requisite to the denomination of new eras. Until then, we must have the courage to witness our unfortunate level of awareness and not fly towards the mirage of another’s ‘time’ on the Concorde. There are no shortcuts; this desert must be traversed on foot.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.