Introduction

We have likely encountered such questions many times, whether in the form of a clear inquiry or as a vague thought: What ensures the continuity of a cultural tradition? How does a culture spread and influence others? Finding appropriate answers to these questions is of great importance to us, as we sometimes encounter aspects of our culture that clearly extend from the depths of history to more recent periods. These might be a plant motif from the Parthian school dating back 1,700 years, a piece of carpet from 2,400 years ago, or the remnants of a garden that is 2,500 years old. When faced with such things, we suddenly find ourselves inheritors of a very ancient tradition. Living within such a culture might make this heritage seem very natural and self-evident; so much so that, while strolling through Fin Garden, or walking in Shazdeh Garden or Eram Garden, we might rarely think about the antiquity of the tradition behind these gardens, which are the most recent examples of an ancient practice. We might not ask ourselves: What idea has allowed this tradition to endure for so long? Does the continuation and evolution of this garden design imply the persistence of the cosmology that underpins it? And can we find traces of the roots of our present-day beliefs, values, and approach to existence within it?

We want to know whether a cultural tradition can continue to survive despite disruptions, fluctuations, devastating invasions, and repeated destructions. And if it can, how can it be recognized after millennia and through continuous renewal?

In this lecture, we will focus on the topic of gardens and garden design. The term “garden” here does not refer to orchards, agricultural fields, or areas of natural wild plants. Instead, it refers to specific areas of greenery with a designed infrastructural pattern, which we will attempt to describe in more detail. This lecture aims to demonstrate in what sense it can be claimed that the garden is the primary image and conception of the spirit of Iranian culture.

In most, though not all, foundational civilizations 1, the idea of “garden design” as we understand it has manifested. Historical records speak of gardens in ancient Mesopotamian civilizations and in the ancient culture of the Near East—although this tradition did not continue and was subsumed into the concept of the Promised Paradise. We also find specific garden design patterns in Latin culture as well as in the Far East. Each of these types of gardens, in their fundamental design, emerges from and embodies a particular form of ontology. For example, the spirit of Far Eastern culture, which shaped the wisdom of Daoism and a branch of Buddhism, is also revealed in garden design. The seeker listens to nature and, sitting under a tree, hears the sound of cherry blossoms unfolding. Here, the main theme is reverence for nature, or “Dao”. The hierarchical wisdom is evident in the special attention given to ancient trees, which become the focal point in this type of garden design. These gardens are artificially designed to appear as though they are untouched corners of nature. Although the space is shaped through refinement, elimination, and reduction, every effort is made to ensure that no trace of human intervention in nature is visible; the essence of these gardens is “non-creation”.

As mentioned in previous lectures, the main focus of art in Far Eastern cultures is establishing a relationship between positive and negative space. In music, too, the silent intervals are given precedence over the melody itself. In Japanese rock gardens, the empty sandy space between the stones evokes the idea of emptiness surrounding all things. The grooves in the sand around the stones and rocks resemble an ocean encompassing the islands of Japan; here, the empty space is the primary player.

In both Far Eastern painting and garden design, the focus is on the site where an external event occurs, allowing the viewer to enter and explore the inner realm. 2

The product of garden design in the Latin tradition, much like its painting art, is the creation of a landscape, or in other words, an “icon” presented to the viewer. 3 The viewer’s perspective is what anchors the scene and defines the spatial experience. In Latin gardens, the space is typically vast and serves as a representation of a world into which one can be fully immersed. The trees, pruned and decorated into highly organized shapes, contribute to creating an external vista that does not offer the viewer a means to enter the inner realm of the work. Gardens often feature labyrinthine designs, and walking through a maze is akin to solving a puzzle, where escape is only possible through trial and error and testing one’s fortune. This reflects the presence of a tragic spirit within this cultural domain. Engineering techniques and creativity in the design of tall fountains, massive water features, and sculptures work to awe the viewer before the grandiose icon that lies before them.

When confronted with a plant motif from the Persian school, at least 2,500 years old, which clearly represents the ancestor of what would later be known as the arabesque; or a piece of carpet from the same period with a design very similar to those woven up to the present day; or the remains of a garden plan from this era, closely resembling the gardens still alive and maintained in various cities, we suddenly find ourselves inheritors of a very ancient, yet remarkably familiar and proximate tradition. This tradition has persisted and remained vibrant through numerous forms up to more recent times.

It is appropriate to consider the cultural journey that has nourished these arts in terms of the connection between seemingly disparate pieces across a vast geographical area and a long temporal span. We should ask: What idea has made these creations so generative and enduring?

The oldest surviving remnants of Iranian garden design are found in the artifacts of the Persian school. The remains of the gardens at Pasargadae reveal a distinctive garden design tradition that astonishingly continued dynamically into the garden designs of two millennia later, such as those in Fin Garden in Kashan.

In the epic cosmology of Iranian culture, the “idea of the garden” is not merely on par with other concepts. The garden represents the triumph of beauty and harmony over barrenness and ugliness; it is a realm established through labor and effort, realized through a determined will to transform the world. The garden is the product of striving to actualize the beauty of the cosmos and elevate wisdom, culminating in the creation of a splendid city. It can be seen as an ideal symbol of realm, city, and concept of sanctuary and country in Iranian thought.

At the same time, within the epic geographical system of the Seven Climates, the garden opens a window to the Eighth Climate; this realm is grounded in historical significance and represents a space where the spirit finds refuge, or in other words, where the capacity for spiritual habitation is provided. It is a utopian land that embodies the pinnacle of the aspirations and ideals of this culture.

In Greek writings, including those of Herodotus and Lucian, we frequently encounter references to the fact that among the Iranians contemporary to them, the construction of temples and sacred places was not common. Sacred temples, which were very prevalent in other civilizations and continued throughout history, were based on specific religious texts. These places generally belonged to a particular group of believers with a specific and uniform faith, and they often kept their doors closed to outsiders.

The main point of difference noted by these historians in Iranian culture, which they reported as the absence of temples, was precisely this lack of segregation between insiders and outsiders. In other cultures, such distinctions were made through the allocation of specific spatial areas—such as buildings, neighborhoods, or even entire cities—to particular groups. 4

In Far Eastern garden design, the main focus is on contemplation of nature and reverence for the Dao. The hierarchical nature of this culture is reflected in the special attention given to ancient trees, which are central to the design of these gardens. These gardens are artificially designed to appear as though they are untouched corners of pristine nature. Although the space is shaped through refinement, elimination, and reduction, the aim is to ensure that minimal traces of human intervention are visible.

Japanese culture, which is the backdrop for the development of sand gardens, emerges from an island climate that is both industrious and inherently unstable. In everyday life, people constantly face the threat of catastrophic events that can disrupt their lives. The sand garden landscape embodies a pause between existence and non-existence; it is as if a wave has rolled through, and the overwhelming force of nature has washed everything clean. The sand garden represents the fixation of this very moment.

Arts born from this way of thinking depict the supremacy of dominant natural forces over humans. Masterful painters of this tradition created long scrolls illustrating majestic landscapes, the power of storms, the grandeur of mountains, and the dominance of awe-inspiring natural elements, where finding the slender and small figure of humans amid these scenes is a meticulous task.

In the construction of Iranian cities, great attention was given to roads and the connectivity of cities, as well as the integration of diverse peoples and residents of various regions. This was based on a specific concept of “participation”. As previously discussed, the calendar of festivals was a historical measure that operated beyond ethnic and religious diversity, capable of connecting various groups under its umbrella. The Achaemenid Empire was founded on this concept of participation and expanded it on a global scale. Contemporary cultures, including the Greeks, were unfamiliar with the historical role of “participation” in Zoroastrian thought. In the Greek world, initial steps toward understanding this concept are attributed to Plato, who infused the idea with a philosophical dimension.

In earlier lectures, we highlighted the importance of the calendar in creating a simultaneous framework for holding rituals across a vast geographical area. Now, let’s consider the place of these events: the “garden” as a festival venue, which provided a space for the gathering of people.

On the other hand, the social role of the garden as a space that facilitated both specific and general connections is also noteworthy. During the Safavid era, one of the most prolific periods for architectural and urban projects in Iran, reports from European diplomats, travelers, and merchants indicate that gardens served as public spaces. Even the gates of royal gardens were open to the general public—an aspect that can be compared with the role of European gardens up until the 20th century.

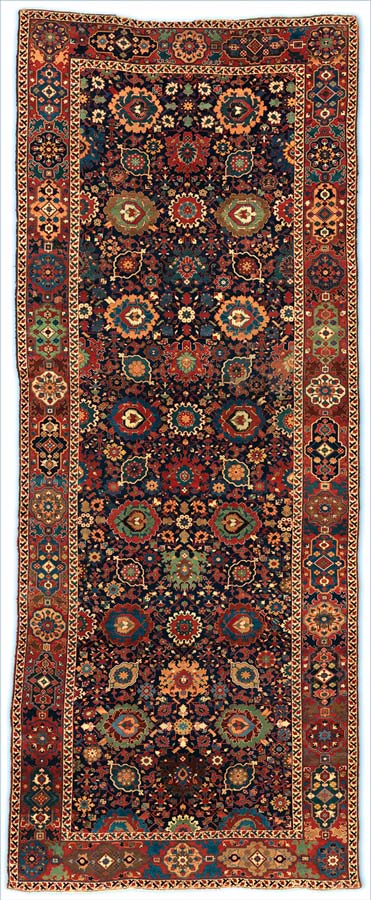

We believe that the design of the Iranian garden is key to understanding the fundamental aspects of Iranian art; it is a unique model that can be examined as a core theme of Iranian artistic expression. This singular heritage, which developed alongside the evolution of thought in the Persian school, achieved such profound influence and enduring continuity through historical intricacies that it permeated all aspects of culture and can still be seen in later periods. The garden not only served as a design model for creating numerous landscaped areas but also influenced the design of all aspects of life, from residential courtyards to the carpets underfoot.

The footprint of the “garden idea” can be observed across various branches of Iranian art, including visible works, poetry, and even more abstract forms like music, which are intrinsically connected to this cosmology. The presence of the garden idea in this broad field is so pronounced that the Iranian garden can be considered a reference model for Iranian artistic works. It is therefore fitting to recognize and study it as the embodiment and concept of the “Iranian cultural idea”.

The product of Latin garden design, much like its painting art, involves creating a “landscape”, or in other words, an “icon” for the viewer. The scope of these gardens is typically vast, symbolizing a world into which one has been cast and can become completely lost. Trees, meticulously pruned and arranged in highly organized patterns, serve to shape an external vista that offers no means for the viewer to enter the inner realm of the work. Engineering techniques and artistic sensibilities in the design of tall fountains, massive water features, and sculptures are employed to awe the viewer with the grandeur of the spectacle before them, creating an impactful monument.

It is said that Napoleon once got lost in this labyrinth, and that Hitler and Mussolini, during a visit to this palace, chose not to test their luck in it.

In the tradition of Latin garden design, it is common to create labyrinthine spaces within gardens using walls of dense and orderly vegetation. Entering these mazes is akin to solving a puzzle, where the only way out is through trial and error, often accompanied by a sense of luck. This reflects the presence of a tragic spirit within this cultural domain.

As noted, the garden embodies an “idea” about a beautiful and flawless world; this idea is manifested in a specific “form” which allows for the content to be revealed within it. Through the experience of this triad, each observer can, according to their understanding, grasp the “fourth layer”, or the historical essence of this culture.

In this article, we aim to highlight key points that will guide the understanding of this reference model.

The Emergence of the Garden in Relation to Iran’s Climatic Conditions

The relationship between the concept of the garden and the measures for its establishment in relation to climatic conditions and natural obstacles is a subject of detailed and thoughtful discussion.

The Iranian cultural territory is a region with significant biodiversity and abundant natural resources. Most areas of this vast expanse, as explained in previous lectures, can be classified into the category of “manageable” lands that experience “four seasons” and are “balanced” (equilibrium). As described earlier, in climates that are “self-sufficient”, where food is readily available in nature and basic shelter suffices for survival, there have not been major challenges that drive human departure from natural conditions and the establishment of civilization in the historical sense. Full reliance on natural rivers and abundant freshwater resources has less often led to the emergence of complex and large societies. Conversely, various efforts in water management are foundational to the development of civilizations. In some manageable lands, water management has required draining water from low-lying and marshy areas, while in other regions, the primary issue has been the collection of scattered waters or the transportation of water.

In a historical civilization, major issues, including the critical matter of water, rely on several fundamental capabilities: foresight, planning, the cultivation of relevant knowledge, and an understanding of crises. The definition of “crisis” is particularly important in this context; a crisis is not only related to natural disasters but, more significantly, is a concept rooted in social and civic dimensions, and thus is a subject of political science.

Some of the oldest indicators of the Iranian garden are the stone channels and pools preserved at the site of Pasargadae. The remaining remnants reveal geometric rectangular divisions, defining the layout of the complex structures within. The design of this garden’s plan is very similar to later versions of Iranian gardens, where the central element of the design is the circulation of water, and the channels divide the garden into rectangular sections.

The simultaneous emergence of these gardens with the establishment of other institutions is significant. The flourishing of garden design over the subsequent millennia, and its remarkable influence and productivity in other cultural spheres, reflect an idea that undoubtedly has deep and fundamental roots within this culture.

The fundamental issue in the emergence of great civilizations and population aggregation was the management of strategic reserves and the storage of water. Additionally, issues related to sanitation, water purification, and wastewater management were of critical importance. The Roman civilization, despite having abundant rivers such as the Tiber flowing through the city of Rome, did not rely solely on these natural phenomena. Instead, one of the key elements of Roman cities was the execution of massive water aqueduct projects. By constructing large bridges that spanned valleys and mountains, water was transported to populated centers and filled storage tanks. This was a feat that, for a millennium afterward, no European peoples, even in water-rich regions, could replicate, resulting in persistently low water sanitation and hygiene.

The ability to harness and control water resources was one of the most significant reasons for the Romans’ dominance over their extensive territories. Military outposts and centers of power in Roman-controlled regions, whether dry or marshy, provided clean and durable water to their territories through engineering expertise and expenditure. This was a blessing that local populations in their natural climates lacked. Meanwhile, contemporaneous peoples such as the Gauls, Celts, Anglo-Saxons, and Germans continued to live within untamed natural environments.

In the context of Chinese civilization, the transformations of dynasties were often closely tied to the management of water. The dominance of powers over vast territories hinged on solving the difficulties of accessing remote areas, accelerating transportation, and facilitating trade through the creation of massive waterways. The implementation of large-scale canal projects could only be achieved through the formation of a strong central government, extensive collective labor, and widespread obedience.

The Indian subcontinent, which is one of the five founding centers of civilization, is composed of both effort-dependent regions and vast, self-sufficient lands with abundant and accessible resources. These two types of landscapes have produced two distinct spirits with different values and teachings. The dominance of the culture in the vast, self-sufficient lands has acted as a barrier to the development of extended civilizational infrastructures.

In previous lectures, we discussed the significance of the calendar in creating a framework for synchronizing ceremonies across a vast geographic area. Now, let’s consider the location of these events: the garden, as a place of gathering and celebration.

From another perspective, the social role of the garden as a space that facilitated both public and private connections is also noteworthy. During the Safavid era, one of the most prolific periods in Iranian architecture and urban planning, European travelers’ accounts indicate that gardens served as public spaces.

Chardin writes that in these delightful gardens, they built magnificent pavilions, and the main pavilion was named “Eight Paradises”, where the king would sit. However, there were also smaller pavilions, or “hastis”, built for public use. On holidays, people would spend their time in these gardens, and the fruit from the trees was freely available to everyone. It is noteworthy that the Farahabad Garden, located in the Thousand Garden region of Isfahan, could accommodate more than half of the city’s population.

The creation of shared public spaces between the elite and the general populace, establishing a connection between the ruling power and the people, is considered one of the thoughtfully addressed challenges in the modern world.

The emphasis here is on the climatic conditions, which have nurtured different capacities in the spirit of their inhabitants. Now, let us consider some common interpretations of the origin of the Persian garden. For example, we may ask whether, as some commentators suggest, the aridity of the land can be considered the fundamental factor in the creation of Persian gardens.

In response, several points should be considered. Neither aridity nor water abundance, in any part of the world, has ever been the sole factor in the formation of a garden design school.

On the other hand, aridity is also present in many other parts of the world, without giving rise to examples of garden design ideas. Even the mere presence of a dry land has not been sufficient for the establishment of water infrastructure that supports civilizations. In many arid and dry regions globally, due to various reasons that are specific to each case, there has been no systematic effort to secure reliable and continuous water sources. Many habitats in dry areas lack even basic water storage facilities, let alone the establishment of gardens.

Furthermore, Persian gardens were established not only in areas that are now arid but also in regions that are lush and well-watered, within the cultural influence of Iran—such as the Pamirs, Kashmir, Mazandaran, and others. When studying Iranian civilization, it is essential to consider a broad range that includes both the well-watered areas of the Vararud and the Mesopotamian region, which are foundational to the development of Iranian culture. The dryness of some regions is as problematic as the cold and harsh weather, or the rainfall and flooding, and marshy lands in other areas could disrupt stable urban life.

Some researchers explain the Persian garden design in relation to the mountainous terrain of the Iranian plateau, considering its location along the path of a spring or an aqueduct. However, it seems insufficient and unbalanced to explain the garden solely as an extension of the natural water flow (mountain, spring, river, valley).

Interpretations that focus on a single characteristic often fail to provide a comprehensive perspective. Additionally, such theories, which base their explanations on the dependency of humans on natural conditions, overlook the significant human interventions and adaptations present in this culture. While these theories can be useful in explaining certain elements, such as the orientation of the Persian garden, they fall short in providing a meaningful connection between the various components of civilization within this vast and historically extended region. They tend to ignore major productive areas located in the plains, such as important projects in the Merv, Nahrawan, and Kandovan plains of Mesopotamia, which were carried out for flood control, land drainage, and water storage predictions. 5 Although riverine civilizations flourished in certain regions, such as Khuzestan and Sistan, a study of some of the mountainous habitats, such as the Central Alborz, up to the 4th century and for some time thereafter, reveals that settlement was not concentrated in valleys and along rivers but rather on elevated areas.

In various arts, not only the depicted scenes or botanical decorations but also the overt or underlying geometry of designs are often inspired by the garden pattern.

In various arts, not only the depicted scenes or botanical decorations but also the overt or underlying geometry of designs are often inspired by the garden pattern.

In a historical and expanding trajectory, the role of garden motifs has gradually permeated various arts and crafts. These motifs are not only found in fabrics, tablecloths, the finest garments, ceramics, and architectural decorations, but also in gravestones and, perhaps most evidently, in many carpets. These patterns are rooted in a world shaped around the garden idea, embodying themes of joy, friendship, love, and wisdom.

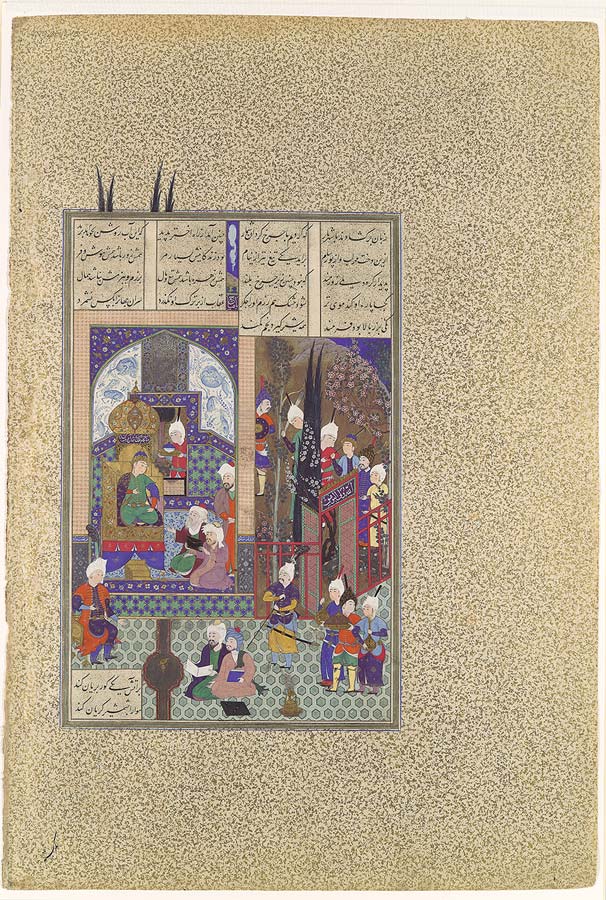

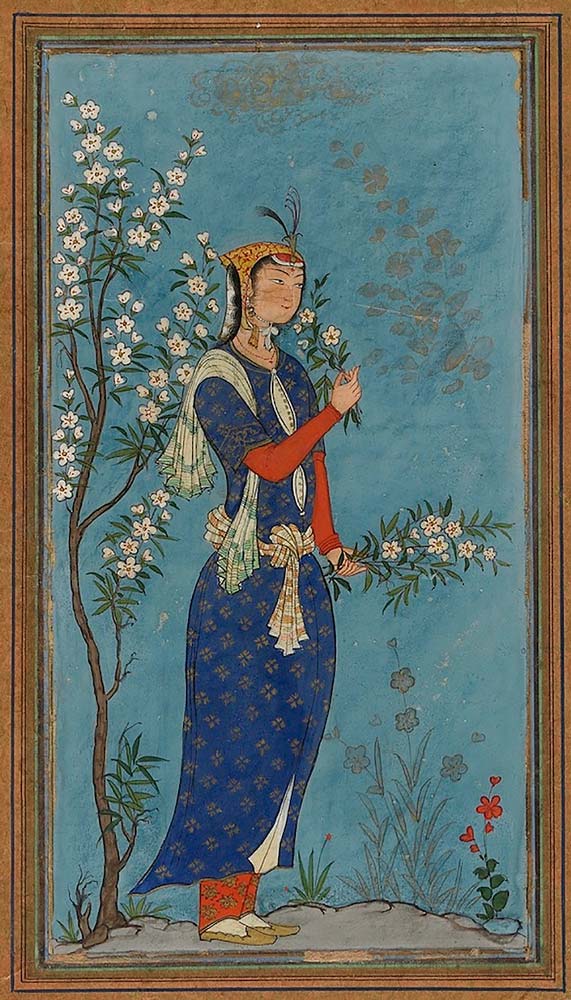

Some designs directly narrate stories, depicting scenes of these stories set within garden corners. In miniature painting, the prevalence of banquet, visit, and conversation scenes set in gardens and pavilions is notable.

Furthermore, significant events in poetic narratives often have gardens as their explicit backdrop. For example, most of Nezami’s Haft Peykar (Seven Beauties) unfolds within gardens.

In essence, just as carpets represent a garden underfoot, they symbolize the daily living space for everyone.

In its historical development, the garden has provided a space that can be seen as a reflection of the soul of this culture; the observer in this mirror will find the most fundamental ideas of this culture.

Here, the establishment of the garden is considered the result of efforts to preserve the grandeur of the world and the value of life and spirit, and to uphold Asha (beauty, tranquility, order, and justice); it serves to revive the hope of virtues in the hearts of the people.

On the other hand, attention must be paid to the historical climatic changes in the land where the earliest remnants of the Iranian garden have been found. During the period that, according to evidence, is considered the early phase of this idea coming to fruition, the lushness of the Persian region and its abundance of water were renowned. Additionally, the climate of the ancient Medes and the realm of Elamite civilization in Anshan and Khuzestan—on which the achievements of the Achaemenid Empire were partially built—were all regions that were abundantly watered in ancient times. Descriptions by some Roman historians in later centuries of the cities and capitals of Iran are scarcely imaginable; for example, they write: “The dense forests of the Persian region are a major natural barrier that makes access to this area impossible.” 6

Today, after millennia, it is incorrect to attribute the motivation behind the creation of Iranian gardens and the idea of their creators solely to the arid nature of the land, without considering the climatic transformations of the Iranian plateau, which intensified particularly after the 4th century AH. According to historical records and accounts from historians, the natural conditions gradually changed during this period. Evidence indicates several major earthquakes across the region, and also, scattered lakes in the central plateau gradually dried up, leading to significant climatic changes. The extent and speed of these changes can be clarified by consulting paleogeological and paleobotanical data.

Nevertheless, even in earlier millennia when the land was greener than today, the occurrence of periodic droughts is undeniable. Such phenomena present significant challenges for any civilization based on agriculture. In Zoroastrian thought, the concept of combating the Ahriman of drought has very ancient roots. In some Persian documents, including Darius’s inscription at Behistun, droughts are mentioned. However, these texts refer to “droughts” rather than an entirely dry land, and the term used in Old Persian for this purpose is “Doush year” (meaning “year of hardship”).

It is a mistake to explain the motivation behind the creation of Persian gardens and the ideas of their creators solely in relation to the arid nature of the land without considering the climatic changes of the Iranian plateau over millennia.

One must note that among the reasons for the emergence of the Kassite civilization in the central plateau of Iran and the growth and prosperity of the regions of Raga (Ray) and Sialk (Kashan) were the high water levels and fertility of this area. Archaeological excavations at the Sialk mound in Kashan reveal evidence of regular transportation and the presence of docks.

Additionally, research in plant archaeology at the Paris Botanical Institute has identified seeds and roots of plants specific to humid regions near the central plateau’s habitats, such as olive trees. Occasionally, rare and very ancient examples of these trees still survive in the mountains of this region.

In any case, the climate situation never remains stable anywhere. Over the past millennium, Iranian civilization has faced significant changes, and today, multiple factors have exacerbated its crisis. The current crisis more than ever demands a return to and reevaluation of the coordinates of historical awareness. In such predicaments, the ability to innovate and apply fresh and effective strategies heavily depends on the wise understanding of the foundations of their historical thought.

As previously discussed, the area of cultivation, spanning from the Amu Darya to the Euphrates, from the Indus to the shores of the Black Sea, is a region that has nurtured civilization. 7 It was in this land that the first stable experiences of settlement, the domestication of plants and animals, the invention of pottery, the extraction of iron, and the creation of bronze took root. One of the key characteristics of life in such conditions, as mentioned earlier, was “voluntary irrigation”—meaning that access to reliable water resources was only possible through careful planning and effort. Among the significant achievements of living in this climate was the development of the “qanat civilization.” In such a civilization, the construction and maintenance of water infrastructure required strong and sustainable social structures that could connect cities and scattered communities. This situation was in stark contrast to the conditions of climates like that of the Greek civilization, where a fragmented system of city-states emerged.

In Iranian architectural art, and most notably in the design of gardens, a doorway to the spiritual realm is opened through the elements, establishing a balance between the inner world and the external environment. The four elements (water, fire, earth, air) are not only employed for their material properties in design but are also contemplated for their ability to purify the soul.

Light is the origin or the initial seed; wind sets the world in motion; the spiritual and physical tranquility of humans is achieved between water and earth. Water is associated with fertility and growth, and the earth, fertile and pregnant with countless seeds, is also nurturing. Therefore, both water and earth are considered feminine.

“Light” (fire) is not merely a simple and pure material illumination, but it also symbolizes the light of the soul (Khvarenah). “Light” is considered a metaphor for the beginning of time, the source of awareness, and the essence of illumination. Reflecting on the function of light, architects have employed complex techniques in designing motifs that have a “dual” function; they change shape depending on the angle of sunlight and appear or disappear accordingly. Additionally, large square water features, located in the middle of streams, create a seeming stillness of water and bring the light of the sky to the earth through reflection.

This way of life was entirely dependent on the flourishing of sciences, most notably mathematics. The development of applied mathematics, analytical geometry, and especially trigonometry, which evolved from beginning to end within this culture, 8 as well as the refinement of the calendrical system, emerged from climatic conditions and the need to address challenges posed by nature.

Mathematics is the most abstract of sciences. The emergence of abstract thought was what gave imagination the power of flight. Abstraction renders the material world insignificant against the boundlessness of the spiritual world of thought. 9 Thus, the spiritual world developed and flourished in contrast to material reality, and through this process, a miracle occurred: the “elevation of matter to meaning.”

This challenging climate, which can only be overcome through hard work and perseverance against dryness, humidity, cold, heat, and its undulating terrain, established a structure in its culture and art that can be interpreted as a continuous effort to reconstruct the world and establish a city of goodness. The city of goodness emerges with a “renewal” of existence. In the Gathas, it is mentioned that to understand this secret, Zoroaster seeks guidance from Ahura Mazda (Yasna 34:6). The response is that this renewal of existence is accompanied by a new creation (Yasna 48:2). Zoroaster uses the term “Frašgird” for renewing this world (Yasna 30:9 and Yasna 34:15). This term is related to the European words “fresh” and “fresco.” 10 Frašgird signifies bringing the world to a dynamic, continuous state of perfection and becoming.

Here, the reconstruction of the world and the establishment of a city of goodness are not narratives concerning the eternal or the infinite, and the creation story is not merely an account of a cosmic battle. Instead, it is an interpretation of human responsibility and each individual’s effort throughout their own lifetime. 11 Thus, spiritual matters are not far removed from human experience but are tangible factors in everyday life. Following this perspective, garden design or architecture is such that at every angle, there is a sense of connection to the spiritual realm; each threshold is a point of illumination by meaningful light, and every corner serves as a support for human connection to an ideal existence. It is important to note that this design emerges from a world where matter does not stand in opposition to spirit; rather, the well-being of the world is realized in the complete harmony of these two elements.

“Frašgird” is the renewal of the world and bringing it to a dynamic, continuous state of perfection. The garden is an ideal model of this renewal in its most beautiful form. One of the prominent examples of extending the concept of the garden into the arts is the “carpet.” Often, the rectangular field of carpets is covered in a balanced and expansive manner with plant motifs. These motifs are placed within a geometric structure that typically creates symmetrical divisions through cross patterns. Additionally, a border in several rows firmly defines the boundaries and limits of this space.

Examination of the Terms of the Garden

One of the fundamental concepts in spiritual wisdom, which has influenced Iranian art, culture, and urban systems, is the concept of divine “grace.” In this cosmology, primordial grace continues from the very beginning. This meaning is expressed in the first hymn of the Gathas with the word “Yān” 12 (Yān signifies life, vitality, and youthful strength). In the Gathas, Zoroaster refers to the divine grace as the “Yān” of Ahura Mazda. 13 The establishment of the city of goodness is Zoroaster’s great promise and the main message of his prophecy.

On the other hand, the Gathic term “baga” (بگا) is a neuter noun meaning “portion”, derived from the root “bag” (بگ), which means “to divide”. 14

From this ancient linguistic root, we find the Sogdian “by” (بای), meaning “piece” or “parcel of land”15 ; the Khotanese “baga” (باگا) ۱۶; the Armenian “bag” (باگ) ۱۷; and the Persian “bāgh” (باغ), which means “garden”. Additionally, the words “Baghistan” (بغستان), “Baghestan” (بَجستان), and “Baghdad” (بغداد) also derive from this shared Avestan root.

The verb “to bestow” in modern Persian also derives from this root. 18 Thus, there is a subtle connection between the word “bāgh” (باغ), in its most fundamental sense of “a portion of land”, and the abstract meanings of “grace” and “generosity”.

“Generosity” is one of the most important attributes of “Saoshyant”. The deity Mithra (Mitra) 19, who bears the title of Saoshyant, acts as an intermediary between Ahura Mazda and humanity; he is a savior, benefactor, and bestower of grace. For this reason, Mithra is referred to as “Bag” (بَغ) or “Bagh”. 20

The sculptures of pre-Christian Mithraea depict Mithras as a young man sitting on the back of a bull, plunging a dagger into its shoulder. A scorpion is stinging the bull’s testicles, a sheaf of wheat is sprouting from the bull’s tail, and a dog and a snake are moving towards the spilled blood of the bull.

This frequently repeated scene holds significant meaning for the worshippers of the deity Mithras. To interpret the meaning of this sculpture, it is necessary to refer to another Persian term for “garden,” namely “Pairi Daeza” (پَئیریدَئزه) in Old Persian, which is adapted into Arabic as “Firdaws” and appears in Greek as “Paradisos” and in English as “Paradise.” Notably, the first part of this term, “Pairi,” meaning “to plow or till,” 21 can provide insight into the deeper significance of these sculptures.

Words used to name a garden illuminate the idea embedded in it. The term “garden” derives from the root “bāgh”, meaning “portion” or “section”, and also “grace”. Thus, anyone who is an intermediary of divine bestowal is referred to as “bāgh”, including the deity Mithras.

Another name for the garden is “Paradise” or “Pairi Daeza”. The hidden meaning in this name can also be understood through European iconography. In pre-Christian Mithraea, Mithras is depicted performing the act of “Pairi” or “plowing the earth” (the bull), representing the transfer of divine grace to the earth, which results in the growth of wheat from the bull (earth).

In Iranian culture, “Pairi Daeza” or “Paradise” refers to a piece of land that has been set apart where divine grace has descended to earth, thus making it a sacred and blessed domain.

First, let us consider the bull. In ancient Iranian texts about creation, it is said that when the “Gauesh Urvan” (the sacred bull) was slain upon the earth, fifty-five types of grains and twelve types of medicinal plants sprouted from its body. Its seed reached the moon, where it was refined, and various animals were created from it. 22 It is also mentioned in ancient narratives that during the conflict between the Iranians and the Turanians, Ahura Mazda created a bull to mark the boundary between Iran and Turan. 23 The act of killing the bull is often interpreted as an act of creation. 24

In ancient times, the bull symbolized the material world and fertility. The word “gāv” (گاو) is etymologically related to “geo” in Latin, which still refers to “earth” in modern usage. 25 In the mentioned statue of Mithras, as the Saoshyant, he is depicted performing the act of “plowing” or “wounding” the bull. Mithras, as the intermediary or link between cosmic forces and human actions on earth, is shown seated on the bull (earth) with his gaze directed towards the sky (in most statues, he looks upwards). He plunges his golden dagger into the earth (the bull). Here, the role of Mithras is that of “plowing” or “breaking open”. 26

Through the act of “plowing” or “breaking open”, Mithras facilitates the fertilization of the earth by the heavens. The scorpion, symbolizing the scattering of seeds, stings the bull’s testicles; a sheaf of wheat grows from the bull’s tail; the dog stands as a guardian, and the snake (symbolizing life) drinks from the spilled blood of the bull. (In Persian, “mar” means “snake” and also “life”; this ancient meaning persists in the word “bimar” for “sick”. Similarly, in Arabic, “hay” encompasses both meanings of “snake” and “life”.) Additionally, it is important to note that all these animals represent zodiacal signs, each performing its cosmic role in the depiction.

The act of “plowing” or “scratching the earth” also appears in the story of Jamshid. When the earth became too cramped for people and domesticated animals, Jamshid used a “golden plow” to scratch and furrow the soil. 27 With this act, he expanded the land, or in other words, the realm of prosperity, making it more accessible for people.

The association of “plowing” or “breaking the soil” with the realm of prosperity is also found elsewhere. In the “Visperad” 28, the term “Pairi” is used to mean “country”. The term “country” derives from the root “kars” (کرش), and it appears in Fargard 19 of the “Vendidad” (Vendidad 21) alongside the term “Pairi”.

From the same root “Pairi”, terms related to “reverence” and “care” have also been derived. This root implies “to go around” or “to surround” something. 29

Walking through the space of the Abbasi Grand Mosque in Isfahan elevates the imagination; surrounded by four grand iwans and amidst a plethora of rhythmic and varied vegetal motifs, with the openness created by immersion in colors, rays filtering through the purity of the skylights, and the freshness and life-giving pulse of the water in the central courtyard pool, one finds oneself in the serenity of a Persian garden that refreshes and blossoms the soul.

It seems that there is a connection between the ancient word “Pairi” and the modern use of the word “Pir” in the names of many pilgrimage sites and shrines, such as Pir-e Sabz, Pir-e Chak Chak, Pir-e Narki, and so on. This connection likely refers to a sacred place with ancient trees and a spring of water.

Professor Mehrdad Bahar notes that in modern Persian, the words “Pir” and “Peri” used in naming sacred places, which typically feature ancient trees and are often located near springs, are derived from the ancient root “Pairika” (پئیریکا). ۳۰ This emphasizes the deep historical connection between the term “Pir” (meaning a sacred place with ancient trees and a spring) and the ancient word “Pairi”.

Two key attributes of trees have been noted in the earliest human myths: one is the movement of roots deep into the earth, splitting the mother of the earth, and the other is the growth of branches upwards towards the father of the sky. References to this description of the tree also appear in Sumerian literature.

Returning to the word “Paradise” and its ancient form “Pairi Daeza”: the second part of this compound, “Daeza” (دَئِزه), means “enclosed place”. Among the earliest examples describing an enclosed place is the story of Jamshid and the establishment of “Varjamkard”.

In Iranian thought, the first step of Ahura Mazda in a world under attack by Angra Mainyu was to define the boundaries of the world. With his all-knowing wisdom, Ahura Mazda limited the extent of the conflict to defined borders. Similarly, the wise hero, in establishing a garden within the cosmos, follows the same approach; he demarcates a space from the surrounding nature, which, in relation to our cognitive abilities, is boundless and infinite. This process of defining the world forms the foundation for establishing order, beauty, and goodness.

Thus, in the words “garden” and “paradise”, there is a trace of the concept of a sacred place. These terms denote a space with defined boundaries, established on earth by human power and grace, and serve as a receptacle for the divine grace offered to people.

In contrast, in Persian, the term “heaven” has a different meaning from “paradise”. In Zoroastrian texts, “heavenly paradise” is a reward for the righteous and signifies “the best mental state”. In the Yashts, “heavenly time” (vahistik) is associated with eternal or boundless time, whereas “paradise” refers to a place within “the pause of the deity”, bounded by twelve-thousand-year intervals. This concept of heaven made its way into the ancient culture through proximity to Iranian culture. In the Old Testament, the idea of “heaven” does not appear until after the story of Jacob. 31

Wisdom, in the sense of understanding the hidden order of the universe, focuses on how the concealed essence becomes manifest. Tessellation establishes a kind of reciprocal relationship between the circle (the unified whole) and the tetrahedron (symbolizing multiplicity), thus carrying a unique philosophical meaning.

The square, akin to a cell, serves as a fundamental module in Iranian architectural design. In various Iranian architectural traditions, we observe common plans based on square measurements, with an inclination towards circular forms in vertical movement and roofing. This geometric system, rooted in tessellation, is also evident across other Iranian arts, achieving a high degree of complexity and variety. This design principle, based on tessellation, spread and influenced a vast geographical area during the Islamic period, from Andalusia to the Indian subcontinent, affecting architecture, garden design, and other arts.

Geometry of Gardens and the Fourfold Basis in Iranian Art

To uncover the foundational principles of any culture’s wisdom, one approach is to examine the oldest characteristics embedded in its mythology. In this regard, Georges Dumézil, the founder of comparative mythology, made significant contributions. As previously mentioned, Dumézil’s crucial discovery was a tripartite structure upon which the foundations of wisdom, social philosophy, and religious thought in Indo-European cultures were built. Dumézil’s theory has cast light on a wide range of areas, from European Christian theology to the separation of powers in modern governance. However, as previously discussed, it appears that this theory faces challenges in explaining the structure of actions and functions within the Iranian world. 32 It is particularly noteworthy that evidence indicates fundamental changes in shared myths within the so-called Indo-European cultural sphere when observed in Iranian culture. The transition from polytheism to monotheism and the emergence of the negative role of divs (evil spirits) from the earlier deities are significant manifestations of this shift, a change that has not gone unnoticed by most scholars. In previous discussions, we addressed evidence suggesting a transformation in the foundational structure of Iranian culture from a tripartite to a fourfold system. We now aim to highlight how this fourfold foundation is instrumental in understanding Iranian garden design.

In the creation myth, the description of Keyumars, or the first human, indicates equal width and length, evoking the image of a large square. Similarly, ancient tales reference ideal cities; the story of Jam mentions Varjamkard, and the Shahnameh refers to the Dezh Kavus and Gang Dezh. According to the Vendidad (Fargard 2, Verse 28), Ahura Mazda commanded Jamshid to build a “distant paradise” and to place each of the pure creations in that garden.

The Vendidad text specifies that this paradise was square-shaped. After the flood subsides, Jam must open the gate of the garden and emerge from it to restore and revitalize the world.

The design of the Achaemenid royal tombs is a prominent example where the soul and glory of the king-warrior are ushered into the divine paradise through the entrance of a cross-shaped pattern, or the ancient four-part motif. The cross, with its intersecting perpendicular lines, defines a square, which symbolizes multiplicity.

The design of the Achaemenid royal tombs is a prominent example where the soul and glory of the king-warrior are guided to the divine paradise through the entrance of a cross pattern, or the ancient four-part model. The cross, defined by two perpendicular intersecting lines, symbolizes multiplicity.

In upcoming lectures, we will explore the Renaissance period of this culture, which generally began around the 4th century AH (10th century CE).

The evolution in painting occurred with a delay after the Mongol invasions, influenced by the introduction of Eastern Manichaean manuscript art, leading to the development of the Herat school. Among the innovations of this period are the cobalt blue tiles, which are considered significant visual resources of their time. These tiles often reference ancient forms in their overall design and expand upon the foundational elements of Iranian culture, notably extending the concept of the garden.

The designs of buildings and gardens in Iran are based on a rectangular layout, with some notable examples being perfectly square. From the grand temples like Chogha Zanbil to the architecture of the Persian school, ancient four-iwan structures, and the perfected iwan designs of the Parthian and Sassanian periods, such as the palace of Sarvestan, this square plan has been a fundamental aspect of architectural work. This tradition continued into the Khorasani school and spread throughout the buildings of Islamic civilization.

On the other hand, the concept of squaring the circle has held special significance for cosmological mathematicians. Squaring a circle—i.e., drawing a square with the same area as a given circle—was a notable problem in ancient mathematics. From one perspective, it can be seen as translating a circle into a square of equivalent area. The fate of Iranian architecture has been shaped by this interplay between the circle and the square.

The circle symbolizes the qualitative, pure, and boundless realm, while the square represents the quantitative, sensory, and measurable world. In sacred geometry, these two are inherently united; the circle conceals the essence of the world within its hidden depths, whereas the square reveals the world’s essence through its sides and angles. In other words, the process of squaring the circle is a metaphor for making the infinite finite and tangible; it involves transforming the unified and absolute circle into a square, which, in turn, can be subdivided into countless smaller squares. In the realm of sacred geometry, the initial act—moving from the formless boundlessness to defined and manifold shapes—is continually reiterated. 33

In Iranian architecture, the square plan on the ground, which is our place of dwelling, transforms into a circle in several stages as it ascends towards the ceiling, eventually culminating in a point at the highest position of the dome. The design of these stages of transformation has gradually evolved into greater refinement and complexity. In this way, a space is created where the material world of this realm connects with the world of ideas or the realm of meaning, and, in a reverse movement, returns from the abstract to the concrete, material world.

The unit can be represented as a circle, where infinite symmetry within the circle places it beyond logic and comparison on a symbolic level. At the same time, the unit can also appear as a square, which, with its four lines of symmetry, presents the “whole” in a comprehensible scale. The square consists of two pairs of equal and opposing linear elements, forming four faces, thus aiding in the graphical description of the nature of the existing world.

The square is associated with four elements or components: water, earth, sky, and fire. The foundational principle in the design of Iranian architecture and gardens places significant emphasis on these four elements.

In Iranian arts—such as gardening, architecture, music, and calligraphy—this framework, and the continual transition between the quadrilateral and the circle, shapes the art forms. In calligraphy, the measure of a complete square is expressed in its “point” form; in music, the system based on “dastgah,” or four alternating tones, is used; in garden design, the “cross” divisions are applied; and in architecture, the quadrilateral plan is utilized.

“The training period for architects, calligraphers, and musicians shared many similarities and often involved forming artistic dynasties, typically within a family, based on principles of divine wisdom. Attention to technical details in crafting instruments and the precise rules established for divine arts allowed for true mastery, leading to the development and writing of calligraphy and music, and the creation of a spiritual space in gardens and architecture.” —from Calligraphy in the Islamic World by Annemarie Schimmel

Overall designs in Iranian arts—whether in garden design, architecture, music, calligraphy, or carpet design—are based on the continuous transition between the quadrilateral and the circle. In calligraphy, the measure of a complete square is expressed in the form of a ‘dot.’ In music, the system is based on ‘dastgah,’ which consists of four alternating tones. In garden design, the divisions are often ‘cross-shaped,’ and in architecture, we see the use of quadrilateral plans and vaulted ceilings.

This realm and language of art infused its spirit into Islamic culture as well, and its influences are clearly seen from the far eastern points of the Islamic world to its western borders in Andalusia. In future lectures, we will explore the Renaissance that occurred from the 4th century AH in the fields of knowledge, culture, art, and Iranian wisdom. 34

In the realm of wisdom, figures such as Avicenna, Farabi, Al-Biruni, and Sheikh Ishraq Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi, among others, revived the legacy of their predecessors. Suhrawardi played a significant role in reconstructing divine wisdom and revisiting ancient Khosrowani traditions. His ‘Hikmat al-Ishraq’ offers a new interpretation of divine thought and represents a renewal of the intellectual tradition deeply rooted in the esoteric dimensions of this culture. Suhrawardi expanded and developed the divine quadrants in his time’s knowledge, including the four human realms, the fourfold series of lights, and the fourfold relationship of objects with light, among others. In his treatise ‘Hikmat al-Ishraq,’ he uses the term ‘Khawarna’ in place of the Arabic ‘Shakina’ or ‘Sakinah,’ referring to it as pure divine light residing in the soul, much like the dwelling of the light of glory in the homeland of the soul. His wisdom returns to the ancient foundations of settled life and the fundamental idea of habitation within this culture. He reinterprets and transforms this worldview in more complex layers. ‘Hikmat al-Ishraq’ extends human habitation in the seven climates to the realm of symbolic and allegorical history and explains divine human habitation in the eighth climate based on past awareness. 35

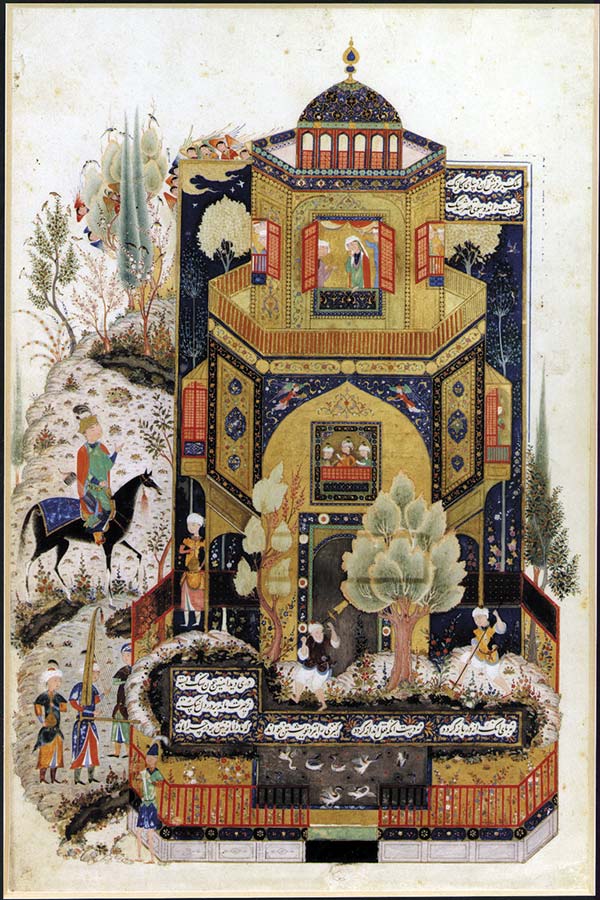

Eight is the symbolic number of the Sun; relying on Henry Corbin’s interpretation of the philosophy of Illumination, we know that the eighth clime is situated somewhere at the boundary between the tangible reality and the abstract realm of intellects. The eighth clime is the abode of the pure and the pious, a spiritual realm where ‘bodies become spiritualized and spiritual realities take on corporeal form.’ Attaining this world is the ultimate goal of art in the Iranian tradition, exemplified by the design of ‘Hasht Behesht’ in architecture, which is a sanctuary within a garden.

In this evocative painting, Shirin is depicted in a pavilion at night, while Khusraw is portrayed in a garden during the daylight. Evidence suggests that the artist was inspired by the Hasht Behesht pavilion in the Shah’s Garden of Tabriz when illustrating the pavilion. The Shah’s Garden was part of the Sahebabad Square complex in Tabriz. This vast square, along with its surrounding structures, served as an earlier version of what would later be constructed as Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan.

(For further reading: “The Garden Landscape: The Evolution of Urban Design and Formation Principles,” Hamidreza Jihani, Maryam Rezaeipour; Tehran: Research Institute for Culture, Art, and Communication, Kashan: University of Kashan, 2017.)

The Concept of Time in the Persian Garden

“Time” is an abstract concept. The history of thought reveals that humanity’s first question was about the nature of existence. From the moment humans perceived existence as eternal and themselves as transient within it, the seed of the concept of time was formed. Thus, time is the product of the first rupture that appeared in human consciousness. It seems that during the era of myth-making, a shared and unconscious concept of time (timeless time) existed among all peoples and groups; an understanding that was the source of the fear of separation from the origin, compelling humans to structure their lives into rituals aimed at reconnecting with the beginning.

This shared understanding of time, like all other concepts, evolved with the development of cultures, and the cultural nature of foundational civilizations gradually became based on different perceptions of time. In one consciousness, primordial time emerged; in another, cyclical time; and in yet another, linear time. As previously mentioned, the lack of a uniform perception of time is a significant indicator of the diversity in consciousness and the formation of distinct cores in the foundational systems of the history of thought.

Now, let’s consider this matter from the perspective of the garden. Here, we want to explore how the design of the Persian garden responds to a particular understanding of time within the world of this culture. From one viewpoint, the Persian garden reconstructs a cosmic event and brings it into our living space. We have repeatedly emphasized the importance of paying attention to the creation story, as it reveals the core idea of each culture and enables a better understanding of the art of any cultural domain.

In the creation story within ancient Iranian texts, several key themes stand out: the depiction of a great cosmic battle across the expanse of the world and time; the movement of the world toward its ultimate destiny, where the triumph of good over evil and the dominance of Asha (truth, order) over chaos are realized with the help of humanity in this struggle. The result of this idea elevates the status of humanity, the world, cultivation, and joy, emphasizing the importance of expanding beauty in the material world as much as possible.

In comparison, consider that the fundamental idea of ancient culture, in its promise of eternal paradise, has an implicit relation to the belief in the transience of the material world. The central message here is the promise of the return of fallen humanity to its original abode. Thus, time is defined by the axis of return to the beginning. For example, in Christianity, time begins with Adam’s sin and his fall. The most significant moment in the history of God (the Father) occurs when He enters history through incarnation in the form of Christ to save human souls, offering a promise for the future—a return to the Kingdom of Heaven. This foundation led to the establishment of “soteriology,” which proclaims the forgiveness of humanity’s sins upon accepting this new invitation. Within this awareness, the burden of time rests primarily on the past and the future, and amid these two immense horizons, the present seems lost and insignificant.

Eight is the symbolic number of the Sun; the eighth clime was considered the abode of the pure and the pious. Henry Corbin, in his interpretation of the philosophy of Illumination, explains that the eighth clime exists at the boundary between the tangible reality and the abstract realm of intellects. In that place, “bodies become spiritualized, and spiritual realities take on corporeal form.” The ultimate goal of art in this culture was to give form to this world, and one of the finest examples of this is the architectural design of the “Hasht Behesht” pavilions, which are sanctuaries situated in the midst of gardens.

In Hindu thought, humanity is trapped in an endless cycle of rebirth, with individual salvation defined by the soul’s escape from this futile cycle. On a broader scale, time is seen as cyclical, and it is believed that one day the dark age (Kali Yuga) will give way to a golden age once again.

In Chinese culture, the world is considered the realm of action, and what shapes our world is “action.” However, this world is not the ultimate reality. To reach the ultimate truth, or Dao, one must attain “non-being” (Wu) and discover “emptiness” within oneself. Opposites such as “Yin” (the shadow side) and “Yang” (the sunny side) are enclosed within the circle of “time.” Time flows between two infinities, a flow that, like the Dao, has no discernible beginning or end. In this sense, the perception of time in Chinese and Far Eastern culture differs from linear time; here, time consists of “moments,” moments that pass one after another, reflecting the pulse of the mysterious cosmic void. The world order is hierarchical, with greater cosmic forces presiding over lesser ones, and the most important aspect of this hierarchy is the void. This cosmic void encompasses everything.

In ancient Iranian wisdom, the stationary and self-contained time of Ahura Mazda began to flow with the bestowal of divine glory (farrah) upon humanity, which made humans the helpers of the divine. It was Ahura Mazda’s wisdom that, by setting time in motion and measuring it, transformed the cosmic struggle from an aimless and endless state, which is desirable to Ahriman, into something limited and defined. Within the wise framework of this structure, the world continuously progresses from its beginning toward its ultimate end. This concept forms the basis of linear time, and the system of its beginning and end is the source of the idea of the immortality of consciousness in Iranian thought, which is entirely different from the concept of natural immortality, understood as a return to the boundlessness of the original nature.

In this worldview, there is no promise of an end to the world; rather, the focus is on the continuous renewal and reconstruction of the world.

Nevertheless, the understanding of cultural materials emerging from this worldview reveals that the linear progression of time has its own complexities. Henry Corbin notes that in Iranian epic culture, the past is not behind but beneath the feet of those who pass through it. This suggests that the perception of time in this culture is not one that continuously moves away from the past. Additionally, the attainment of beauty, goodness, prosperity, and justice is not deferred to a future state but is related to the present moment. These are matters that can be realized in the present through human choice to pursue goodness and commitment to prosperity. This reflects the concept of “eternal present” or “perpetual now,” which represents the fundamental difference in the understanding of time in Iranian wisdom compared to other cultural centers.

Understanding the history of qanat construction and the story of Iran’s 150,000 qanat systems can be a key to comprehending the foundations of Iranian civilization. Estimates of the productivity of Iran’s qanats, according to specialists such as Engineer Safinejad and Dr. Kordvani, amount to approximately three-quarters of the annual flow of the Nile River. There are remarkable examples of the scale of these works; for instance, the Qanat of Khosrow in Gonabad, which has been in operation for at least as long as the Achaemenid era, features mother wells reaching a depth of 370 meters and involved the excavation and removal of over 60 million cubic meters of earth. Similarly, the length of the Zarch Qanat in Yazd is 135 kilometers. Some of these qanats took more than a century to construct, passing through several settlements along their route, with successive generations contributing to their construction without expecting to benefit from their fruits within their own lifetimes.

These projects are so grand in scale that they alone demonstrate that in this culture, attention was never focused solely on short-term horizons, temporary solutions, or providing minimal subsistence.

“Say now, what the speaker is digging for / Until a century later, water reaches us. / Though every century has its orators / The words of the ancients were the true aid.”

The metaphor of speech as water is frequently used in Rumi’s writings. From one perspective, it reflects the deep connection between themes of water, prosperity, culture, and discourse in the layers of culture. More importantly, these verses illuminate an underlying philosophy in which the fruits of great efforts are directed towards future generations. Rumi perceives his own efforts in speech as akin to those of a qanat builder, working for the benefit of future generations. Though there will be orators among them, they rely on the support and contributions of those who came before.

Thus, the garden, or paradise, is not a heaven that is promised to be established in another time or another world. With the previously mentioned premises, the world progresses towards a sublime existence through innovation (transformation), and history moves towards its culmination, which is the complete harmony of matter and spirit. The result of such a perception of time is the valuation of human effort in the sphere of daily life. In this way, “work” in everyday life can become an epic concept; it stems from the interpretation of humanity’s voluntary role in participating in a struggle to triumph over the chaos of Ahrimanic forces.

On the other hand, let us again consider the climatic context of the land and the management of water resources. The social prerequisites for large-scale and time-consuming qanat projects are not comparable to the natural behavior of people in utilizing rivers and spontaneous springs. Once constructed, qanats required ongoing maintenance and annual cleaning, with their benefits sometimes extending to future generations. Therefore, the effective use of vital water resources depended not on centralized, coercive powers—which were themselves constantly at risk of collapse—but on a stable worldview, ethics, and specific individual and collective relationships. This stability could only be achieved through the “synchronization” of people scattered across a broad geography and the “continuity” of culture through historical time.

“Synchronization” is a complex concept whose understanding has evolved over time. Today, we observe that, in the absence of inevitable biological pressures that historically drove dispersed peoples together and created more complex societies, fundamental agreements that bind and synchronize communities have not always emerged, even after centuries of neighboring tribes living side by side. 36

In Iran, the continuity of a civilization built on a qanat-based system has depended more on a shared calendar of rituals and festivals, and the enduring structure of collective consciousness, than on any transient central authority. The idea of the Persian garden, as both a symbol and a tangible space, has been a binding element of cultural concepts, historical ethics, beliefs, and the legal system of the Iranian people.

In conventional and historical law, as well as in the regulations between the Waspuharan and Vastryoshans (the lords and landowners), the right to determine the fate and survival of the agricultural system and economic power was more dependent on water than on land ownership. Thus, the regulation and adherence to water distribution rights were crucial and unavoidable.

The Mirab (or “Master of Water,” a title emphasizing the importance of the water distributor’s role) divided the flowing water according to units of “time.” In the central regions of Iran, the time measure for dividing water is called “Serejeh.” It is a small brass bowl with a tiny hole, placed within a larger water container. When the Serejeh fills up, it sinks in the basin, marking a unit of time known as “Sereh.” Each Serejeh is subdivided into four parts, creating a smaller unit equivalent to one and a half “Dangs” (a smaller subdivision), which allows for precise allocation of smaller water rights.

(“Traditional Irrigation System of the Solomon Spring of Fin,” Abbas Torabzadeh, Kashan Research Journal, Fall and Winter 2017)

The use of the word “Peymaneh” to refer to measurement tools for quantity, volume, size, and more broadly “standard” or “scale,” in conjunction with the term “Peyman” (which holds an abstract legal and ethical meaning in Iranian tradition), is thought-provoking.

The concept of “Peyman” is fundamental to the historical texts of Iranian thought, as previously discussed in earlier lectures. This alignment of terms underscores the deep connection between practical measures and abstract principles in Iranian culture.

As mentioned, in the Persian garden, the interplay of the four praised elements—water, earth, air, and light—is fundamental to its design, with “water” being the central element. This water, typically sourced from a qanat or natural spring, enters the garden, circulates through it, and exits from the other side. In this continuous flow of entry and exit, the unceasing bubbling of fountains acts as the pulsation of life within the veins of the world.

This interaction with the element of water reflects a distinctive understanding of the concept of time—specifically, the notion of “eternal present” as described in epic thought. In the gentle flow of streams, each moment of encountering the water is a new experience, embodying an understanding of “continuous present” time.

In design, the emphasis on the non-static quality is achieved through the steady flow of water and the rhythmic pulse of short fountains, adding a musical quality to the Persian garden. This characteristic of music is its continuity in time; musical experience is authentic only in the present moment. The auditory pleasure, whether before or after, is perceived as a “series of connected presents,” making music the art form closest to the concept of eternal present in Iranian epic thought. In this perspective, all existence is the ongoing flow of ever-renewing moments.

The execution of such a scenario with water relies on engineering knowledge and the application of complex methods in designing the water flow. The efforts and intricacies involved in this process, which demanded diverse techniques in different garden examples, highlight the importance of water flow design in evoking fundamental meanings.

The design of the water distribution basin and the regulation of flow pressure at the entrance of the Fin Garden’s spring in Kashan, attributed to the renowned mathematician Ghiath al-Din Jamshid Kashani, stands as evidence of this. (Jamshid Kashani was among the great mathematicians who worked on the problem of squaring the circle. He made significant innovations in solving this geometric problem and, as a result, calculated the number π with unprecedented accuracy.)

In Persian gardens, fountains do not serve to create a grand display or a monumental effect as seen in European garden design. Instead, they are small, rhythmic pulses that provide a space for attuning oneself with existence, which reveals itself in new forms every moment.

Circle and square are fundamental shapes. From the perspective of the evolution of consciousness, the tendency to design based on each of these shapes reflects a specific worldview:

In early societies, most forms (such as habitats, meeting places, and ritual motifs) tend to favor the circle, which represents a unified, seamless whole.

The square, or more broadly the quadrilateral, embodies an internal logic with distinct, separable components and can be subdivided into numerous smaller squares within itself. The emergence of a new awareness in the early cities of this region, which were pioneers in establishing new foundational principles, is evident in the expansion of designs based on squares and cruciform divisions.

The legacy of these civilizations was passed on to the Persian school, which clearly established the basis for the architecture of ritual structures and garden design on square divisions, applied in a more complex manner than in earlier examples.

Continuity and Influence of the Artistic Work — The Persian Garden as Language

In the fourth and fifth articles of this series of discourses, we addressed a defining transformation at the beginning of the history of Iranian thought: the emergence of a new idea that underpinned settled life. It was noted that, based on Neolithic data, some scholars advocate a theory suggesting that the unprecedented durability and expansion of settled life in this region were due to a profound intellectual transformation, beyond mere accumulation of lived experience. This implies that the formation of a new worldview in this area was the primary catalyst for changing people’s behavior, shifting them from a nomadic and food-seeking existence to settled life and food cultivation—a period we recognize as the dawn of agrarian life.

In previous lectures, we discussed the dissemination and transmission of this new idea and its associated rituals to distant regions, which led to the emergence of shared behaviors among contemporary societies. Among the achievements of this new way of life, supported by archaeological data, was a reduction in the frequency of ongoing conflicts for a millennium. Settled culture overcame the innate aggression driven by the natural conditions of earlier life. Following subsequent transformations and disruptions that led to a return to primitive practices of aggression and raiding, a new concept in the establishment of power emerged during the Achaemenid era. This involved renewing the ancient agrarian idea but in a manner suited to the complexities of large cities and rival power centers that had developed during this period.

The Achaemenid Empire, the most enduring and longest-lasting empire in history, was founded on a novel idea that did not rely on the expansion of indigenous thought or the imposition of one group’s beliefs on others. Although there was a defined and efficient military structure, and numerous military conflicts occurred during this period, the power structure, unlike the Roman Empire in later centuries, was not defined by military order. Instead, in a new definition distinct from previous regional powers and subsequent empires, the continuity of the Achaemenid Empire was based on the acceptance of cultural diversity. The result was a society characterized by unity in diversity.

The challenging climate of this land fostered a nature adept at tackling diverse issues, adapting to new environments, and addressing the customs of different peoples. As a result, across this vast territory, power evolved to possess capabilities far exceeding local resources, addressing obstacles and difficulties with exceptional efficiency. This led to the construction of monumental projects such as the Suez and Dardanelles canals—often bearing prefixes or suffixes denoting their grand scale, like Dandara and Daraya 37 —as well as roads, bridges, dams, and ports. More than half of these structures were built outside the Iranian plateau, enhancing the welfare of inhabitants, boosting urban prosperity, and facilitating communication. The long-term continuity of the Achaemenid Empire was made possible by these grand endeavors and massive projects. The Achaemenid approach to mitigating water scarcity in scattered arid regions included building dams, constructing canals, or digging qanats, depending on the specific needs of each area. This model later influenced the strategies of subsequent great empires.

The Pazyryk Carpet, although discovered in Siberia, is unequivocally attributed to the Persian artistic tradition by experts. It exemplifies an artistic school emerging from a new awareness, capable of expressing itself through diverse forms and being distinctly recognized.

Researchers often highlight the geometric order of the carpet’s patterns and the design of its multiple borders, which are characteristics that continued in subsequent Iranian art schools. Another notable feature of the Persian school is the relationship between individual elements and the overall structure of the design. This characteristic led to the creation of works with a “modular” nature—the earliest appearance of the concept of “module” in art history. A module is a unit with an internal logic of creation that allows for replication and expansion.

This logic was later elaborated upon in subsequent art schools, manifesting in intricate forms and the proliferation of patterns based on modularity.

However, no single engineering project alone was sufficient to shape such a domain; rather, the expansion of culture was the major achievement of this era. Bruce Lincoln, a professor of Achaemenid Iranian studies, in a series of lectures delivered at the Collège de France, has highlighted the significant role of Persian gardens in the dissemination of this culture. 38 He considers the Persian garden as a key factor in the dissemination of Iranian culture during the Achaemenid era, with its construction being pursued as a cultural policy across all territories under influence. He explains how the intellectual ideas and new methods of social organization, manifested in the design of these gardens, extended the image and concept of Iranian culture. Lincoln’s theory is based on recent historical and archaeological studies, which have progressively uncovered numerous traces of these gardens in regions under Iranian cultural influence.

The components of these gardens, from the irrigation systems to the architecture and associated motifs, including beneficial and symbolic trees and plants transferred to suitable areas, created thematic elements like words in a language. These elements manifested in other aspects of society. This new alphabet was applied in the design of other places and new bureaucratic centers, and importantly, it provided the general public with direct engagement with the aesthetic world of this new idea.

In this new school of thought, stylization reached its zenith. A narrative based on cosmology unified all layers of each work. Thus, the distinctive style of this school, wherever found—even in a worn piece of handwoven textile in distant lands—stands out. One of the most significant ideas of this school was the design of the relationship between components and the overall structure; the Persian school is characterized by the creation of works with a “modular” nature.

Plato held his discussions and dialogues in a garden called the Academy. Some scholars have noted that this method, which was novel among the Greeks, was influenced by the practices of the Magi.

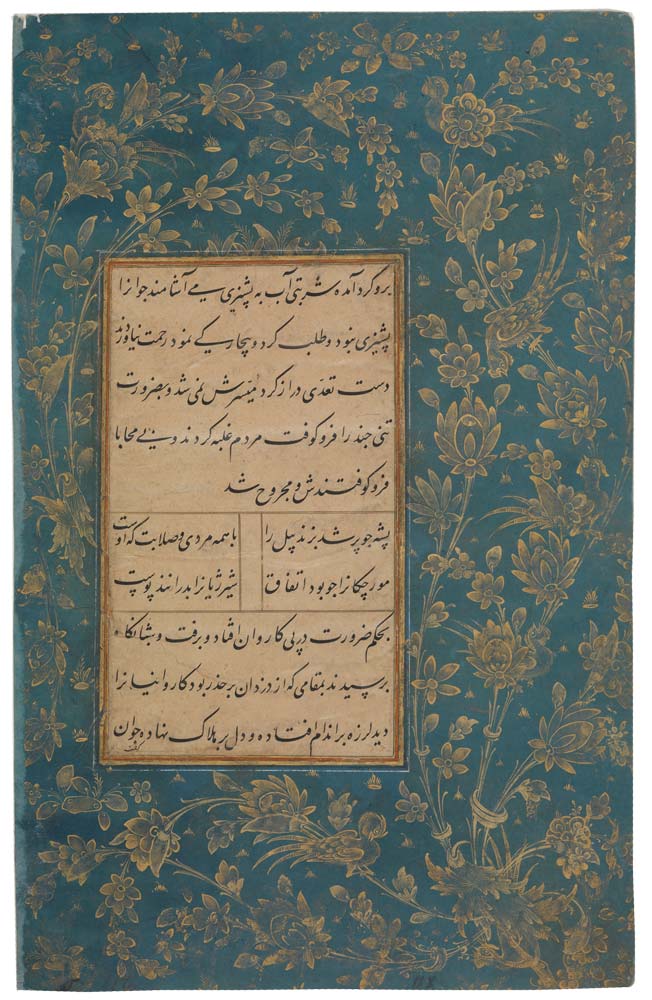

The concept of the garden also found extensive expression in the arts of book decoration. The earliest surviving examples of the tradition of presenting text alongside plant forms, which symbolize fertility, growth, and blooming, are found in the art of manuscript illumination in Manichaean texts. In later centuries, what we now recognize as tazhib (illuminated decoration) reached an unparalleled level of refinement.

This was the first manifestation of the concept of “module” in the history of art—meaning a unit that, based on its intrinsic logic, has the capability for replication and expansion. One of the earliest examples of such modular structure is the Persian garden design. The garden design begins with a cross pattern, which is a simple and very ancient motif. This simple design here transforms into a module that can be replicated and divided, offering enough flexibility for new designs tailored to different conditions. These multiplicities, while diverse, converge under the logic of the overall design into unity.