Let us start the discussion by comparing two renowned Iranian painters of the contemporary era: Bahman Mohasses and Hossein Zenderoodi. I do not think there is much doubt about the creative talents and abilities of Mohasses as a painter. His paintings, such as his ‘Minotaurs’, are very sober and solid, resulting from artistic vision and strong execution. His works are, moreover, not duplications or imitations. An art expert would probably recognize his works without his signature. Even non-expert audiences like me will recognize the authenticity of his paintings and sculptures that remind us of his ‘world’. Hossein Zenderoodi, too, is a celebrated creative painter who has made his unique world. It is different from the world of Mohasses because of the symbols and signs that we Iranians find familiar. Its letters, curvatures, and abstractions are all components of our visual memory which he has rethought and recreated as canvas paintings. That is why just as much as works of Mohasses can seem exotic to Iranians unfamiliar with Western painting, pieces of Zenderoodi might seem peculiar and strange to a Westerner unaccustomed to the shapes in his art. Some kind of defamiliarization (ostranenie) happens here naturally under Western eyes while watching such works.

Bahman Mohasses is a figure of great importance in the history of Iranian painting or, more precisely, in the history of the encountering of Iranian painters to modern Western art. But can his precious works find a place in a west-centered ‘world art’? The answer seems to be negative, as it has not occurred thus far. To the western eye, works of Mohasses are a collection of valuable pieces the likes of which they have seen plenty. How about the works of Zenderoodi? His works, and the works of others like him, at least seem possible to become contributions to the contemporary world art. One can imagine such works finding a place in the global art scene, thus gaining distinctiveness and status therein. And that is what actually has somehow happened. Such status is a result of the Iranian character of the works, that same facet familiar to us and appealing to others. Like it or not, the reality of the world in the recent centuries, the historical state of different cultures with regard to each other, dictates that even when artistic movements do not emerge in the West, they are recognized and evaluated there and introduced to other parts of the world afterwards. That is the case with the artworks of China, India, and Japan, for example. Regrettably, we know those works not immediately through the Indians or the Asians, but through the West. We know these works because of their distinction in the Western/global art market, part of which is due to the specific symbols and significations originating from the artists’ identity. For the time being, it is in the countries like the United States, France, United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Spain that peripheral identities enter into the mainstream and gain status in the global art scene. So it does not matter which artist is more ‘Iranian’: Mohasses or Zenderoodi that, by the way, added the French ‘Charles’ to his name. What matters is identifying and extracting sources of cultural identity to properly presenting them as distinctive factors. Bahman Mohasses was a pioneering innovator in Iran but, at best, a present-day artist in the West. Hossein Zenderoodi is considered a traditionalist in Iran and a pioneering innovator in the West. The ‘time’ of the works of Mohasses was the contemporary period of the West that we were striving to reach. The ‘time’ of the works of Zenderoodi was Iran’s past as a (post)modern future seen from the Western point of view.1

I do not aim here to compare these two artists; you can remove their names and replace them with other similar painters2. My concern is to show the complexity of the state of ‘contemporariness’ in cultures on the sidelines of modernity. In each period of human history, certain cultures have been more active, shaping the mainstream of history, while others have remained somehow latent, thus historically distanced from the dominant culture. In our times, for various social, economic, and cultural reasons, modern societies have provided a platform for sciences, philosophy, and art. In general, the history of each of those fields is mainly equal to their history in modern societies. For now, other countries are assessed in comparison to the status quo in Western societies. I am not being prescriptive here. This is a description of the facts that do not change by our wishful thinking. Consider the field of painting, for example. Modern art contains various movements, currents, and activities that have been developed, established, challenged, and ultimately become classical, giving place to ‘avant-garde’ successors. There are interactions between those developments and other intellectual, scientific, social, economic, and political developments in Western countries. In modern countries, artistic movements are parts of the ‘organism’ of the society. While in peripheral societies, the more they are distant from modernity, the more the organic nature deteriorates, giving way to superficiality and importation. That might even reach a point where something necessary and meaningful over there can be reproduced as incomprehensible and redundant here.

History/historiography is the place for the possibility of multiple comprehensible narratives of the organism of society and its evolutions. Evolving is always assessed in comparison to something else, an origin or an axis upon which past and future are defined. In peripheral societies, the axis is located in the modern foreign centers, while changes and evolutions happen marginally. In such circumstances, the organism falls apart and inevitable dissociations replace meaningful continuities. That is how misunderstandings and distortions are born. Take modernist art as an example. One of its aspects, manifested in its primitivism or abstraction or even in its depiction of absurdity, is the criticism of the modern world along with the quest for some kind of spirituality. This is clearly expressed in the reflections and writings of some artists of this movement, such as Wassily Kandinsky. In a peripheral society like Iran, the same type of art becomes a component of modernity, a means to express interest in the ‘progressive movement’ of the West. In other words, it becomes a shallow mark of being up to date and not marginalized. Even if a few Iranian artists created their modernist works with an awareness of the true meaning of this form of art, the works had a different signification for the majority of audiences, one very different from what modern Western audiences perceived. In contrast, the paintings of Kamal-ol-Molk and his pupils are considered non-modern classical/traditional and, based on our definition, ‘spiritual’, even though they follow the rules of perspective and shading to the best of the artist’s abilities and imitate the understanding of the founders of modernity. Contemporary Iranian art has been developed within such complexity, in the historical distance that separates pioneers of Western art from Iranians and their audiences.

The process of modernization in each form of Iranian art varies, depending on their conditions in society. For instance, since poetry is a deeply-rooted art form for Iranians, Nima Yooshij’s poetic innovations, though heavily influenced by the modern world, were original creations. Despite the efforts of traditionalists, his poetry was well-received by the public and ‘post-Nimayi’ poesy forms and themes became comprehensible forms that appealed to Persian speaking audiences. Prominent poets of the modern movement (such as Foroogh Farrokhzad, Ahmad Shamloo, Mehdi Akhavan Sales, and Sohrab Sepehri) became poets of the day. ‘She’r-e now’ (literally: new poetry) gained such a status that older styles like the ‘ghazal’ had no choice but to accept the ‘Nimayi’ perspective in order to continue competing for endurance and contemporariness3. But novel writing, as another example, was not as deeply rooted in Persian literature. Short stories of Mohammad Ali Jamalzadeh paved the way because people already had an idea of parables. But the solemn focus on modern fictional literature that Sadegh Hedayat sought to establish was initially hard to comprehend, leading to misunderstandings which still exist to some extent. The novel, specifically, came to life with post-renaissance culture, representing a novel view of the world. Therefore, although we have novelists like Ahmad Mahmood and Mahmood Dolatabadi, we still do not have novels as successful as our contemporary poetry. The two exceptionally successful books of our contemporary fictional literature, namely ‘The Blind Owl’ and ‘Savushun’, are respectively, in terms of form and perspective, a combination of poetry and prose4 and a mixture of epic and mythical literature5. These examples from novel writing help to better comprehend the complexity of the conditions of contemporariness for modern arts.

Jalil Ziapoor is commonly considered the first artist who tried to introduce modern painting to Iranians. A member of the editorial team of Khoroos Jangi (‘Fighting Cock’) magazine, he brought Cubism to Iran. As well as introducing the modern painting, he wanted to create a bond between his knowledge of Western art and Iranian artistic traditions. In his paintings, Ziapoor made the traditional square-shaped tiling the basis of his modern works. A glance at his activities demonstrates how enthusiastic he was in presenting modern art to Iranians. But do his visions have an established position in Iranian culture today? He accomplished in his field what Nima and Hedayat had done in their respective fields (acknowledging modern art and linking it to the heritage of the past). Yet he neither found Nima’s rapid and emphatic success nor Hedayat’s late but enduring triumph6.

A work of art does not become so in a void. ‘Conditions of possibility’ of a certain art must be satisfied for a piece of work so that it can be seen as art. Those conditions have hardly existed for Iranian painting. In our collective visual memory, we are more familiar with carpet and Gabbeh patterns or the tiling designs of domes and mihrabs in mosques, but much less so with the art of painting or sculpting. (I am talking here about the current culture which is mostly rooted in the Islamic period, not the outstanding ancient Persian heritage of sculpture and painting that, despite being subdued in the Islamic era, elements of which are remained and reproduced today.) What we consider as the history of Iranian painting before ‘Farangi-Sazi’ usually consists of miniatures in luxurious books to which most people did not have access7. The religious prohibition or at least disapproval of painting and sculpting in Islamic tradition played a significant role here. Instead, calligraphy which faced no prohibitions has become a familiar or even somehow sacred form of visual art for Iranians, practically limiting the space for painting.

Moreover, in the past, the patrons of the few visual artworks were rulers and aristocrats. New audiences are different. One portion of the new audience consists of art buyers. But at the beginning of modern art in Iran, even if they existed, they were either not adequate in number or as knowledgeable in modern art as the artists. So they could not properly support innovation. Audiences of visual arts are not necessarily limited to buyers. They are also a larger group who view the works and follow their evolution. In modernized/developing Iran, the buyers, the followers and also the critics or historians of art who link the audience and artworks were relatively scarce. Moreover, gaining more widespread audiences in world art has always been an issue. In such circumstances, what courses of action did our artists have?

The first possible approach is to strive to create works based on contemporary movements in the West, i.e. attempting to be (or appear to be) contemporary with the West. Contrary to the modern movement in other arts (poetry, for instance), modern painting was directly introduced to Iranians through modern academia. Therefore, such an approach was accessible to Iranian artists. However, by choosing this approach, would the artists become artists of their society or Western society? They seemingly would not belong to their society since they had no audience there. And becoming an artist in another society and culture is much too difficult, with rare exceptions proving the rule. Taking this path, the artists have few options. They either become teachers who introduce Western currents and schools through recreating them (e.g. Ziapoor’s first works that were somehow copies of cubist pieces), or they become mere imitators. In the best-case scenario, they would be someone like Bahman Mohasses, who, despite all of his abilities, never reached a status deserving of his talent, not in Iran nor abroad. With this approach, the main concern is being contemporary, but what results from it will always be an ‘outdated’ repetitious contemporaneity. Imagine a third-world artist who tried to be contemporary to, for example, Futurists. His works would certainly have seemed repetitive and copies of the originals. And they would be also irrelevant to his lived experience in an undeveloped and non-industrial society.

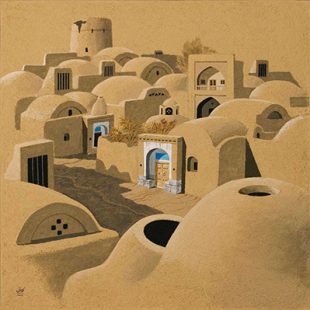

Another approach would be to quit the ideal of contemporariness. If classical art will perpetually have admirers whereas contemporariness always carries the mentioned troubles, why should one not opt for this approach? Especially when, thanks to Kamal-ol-Molk’s legacy, classical works have become traditional in Iranian painting, with art buyers and audiences alike praising their realistic representations. With this approach, the style and the techniques are well-defined. If there are differences, they are, apart from the quality of execution, in the subjects depicted. One can draw landscapes not representing any specific time and place. Another can preserve the nostalgia of old Iran by repeating the subjects of paintings of the past. By taking a slightly higher risk, one can even create more modern images that bear signs of their times, while remaining unchanged in terms of form. The prerequisite for this approach is the ability to create masterful paintings with primarily traditional contents, in which the decorative aspect, the craftsmanship, bears greater significance. The works of Abbas Katoozian are examples of such paintings. They are as impressively skillful as the ‘Qasida’s of Mohammad-Taqi Bahar or the poems of Parvin Etesami, while remaining in the past, with no link to art’s evolving history, lacking the potential to turn into a movement or to innovation.

The third approach is to recreate, to reproduce the traditional themes and forms that have admirers and a market of their own. For example, if Persian miniatures make a part of our illustrative past, we can recreate this past such that Iranian audiences can gain a sense of identity and dignity and, at the same time, Western observers can be drawn towards a less familiar phenomenon. This approach has its constraints, such as being faraway from daily realities, including the marks of times. However, like the previous approach, it requires effort and skill, contrary to some modern(looking) artworks. Elaborate miniatures of Mahmood Farshchian are good examples of works with this approach. Such works will always have an audience. The only problem is that they are not contemporary art but rather masterful craftsmanship. They are beautiful but not challenging, not reflecting the contemplations, questions, and concerns of their time (or perhaps they are incapable of such reflection because of the ‘imaginal’ world beyond space and time in which they are created8). This kind of art has an unchanging character that seems to exude an ‘oriental’ charm enchanting for the Western viewer. But we usually forget that this type of art was alive and vibrant in its own time, experiencing interaction and fusion, albeit at a slow pace. A tradition becomes unchanging and rigid only when it dies. That is why fabricating a tradition according to a cliché of ‘identity’ from the western point of view would be dressing up a corpse.

The final possible approach is to try to create works suited to their time while also using traditional Iranian elements. Such artworks would appear distinctive compared to Western pieces and would manifest signs of the true circumstances of their creation on the margins of modernity. They would be continuations of a tradition, or a fusion of traditions, in the true sense of the word and not just the promotion or imitation of a static interpretation of one specific tradition. That is the approach most artists in peripheral societies find themselves forced to choose, Iranian artists as well. To create art that was global while also remaining local: modern Iranian art.

The use of local present-day elements in artworks, or more specifically the representation of these elements, can have different aspects. Iranian artists have experimented with them all. The first aspect that naturally comes to mind is the representation of Iranian content, from the daily lives of nomads and villagers to native urban life. Another aspect could be using familiar materials as tools for creation; e. g. using clay and straw plaster on canvas. Another aspect could be depicting the old ‘imaginal’ world by the logic and language of modern art, or perhaps the use of traditional Iranian illustrative techniques in a modern framework. Last but not least would be the referencing to our historical background and visual memory, from calligraphy, Persian miniatures, tilings, Teahouse Paintings, and designs in works of lithography to the inscription of religious phrases and the old locks, from the representation of religious figures or national epic heroes to the use of stoneware crocks and ‘sangak’ bread as elements of a kind of Iranian pop art. Almost all of our modern artists have, each in their way, stepped foot on this path. Those who did not, attracted less attention beyond Iran’s borders.

This movement of return to tradition reached its peak at the height of the period of ‘back to self’ based on what I call ‘identity-thinking’ in our intellectual history, characterized by the thoughts of Jalal Ale-Ahmad, Ehsan Naraghi, Dariush Shayegan, and also Traditionalists such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr[9]. What resulted from that intellectual coordination is the only true ‘current’ that bears the emblem of modern Iranian art: what Karim Emami named as the ‘Saqqa-khaneh’ movement10.

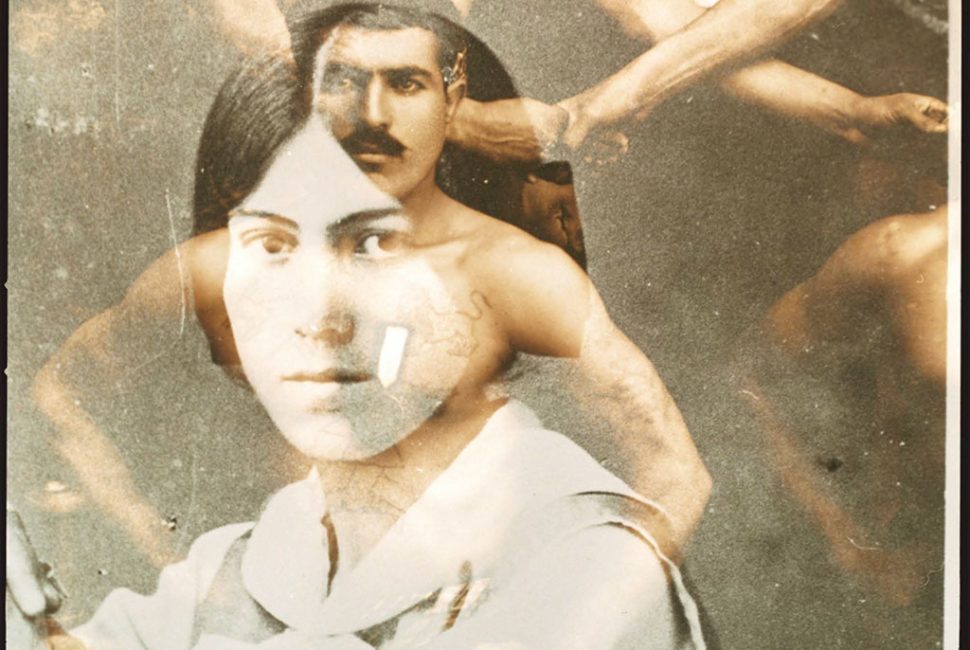

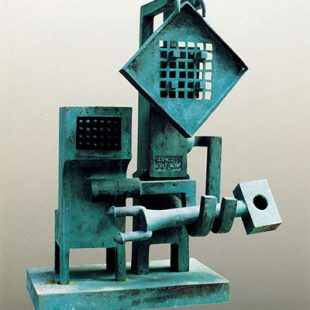

With social and intellectual developments, these artistic references to the past have become more delicate and discrete, sometimes even reaching a point where we clearly witness that nostalgic depictions full of admiration give their place to sarcastic representations. One could say that this style has moved from one stage to another within itself as a result of the change in the society’s value system. Nevertheless, the framework has remained the same. It is still the most significant experience of modern art in Iran, giving rise to, e. g, the urns of Mahmood Javadipoor, the fantastical world of Ahmad Esfandiari, the calligraphy-paintings of Mohammad Ehsaei, Faramarz Pilaram, and Nasrollah Afjei, the calligraphy-filled paintings of Hossein Zenderoodi and Sadegh Tabrizi, the sculptures of Parviz Tanavoli, Jazeh Tabatabaei, and Mash Esmaeil, the illustrations of Ghobad Shiva, the cartoons of Ardeshir Mohasses11, ‘love’, ‘Fresh pomegranate juice’, and ‘Flying carpet’ of Farhad Moshiri, the miniaturized, illuminated Mona Lisa of Farah Osooli, the clay and soil works of Parviz Kalantari and Gholamhossein Nami, the works of Marco Grigorian and Fereydoon Ave, the noticeable borrowings of Nasser Oveisi, Mansoor Ghandriz, and Mohammad Ali Taraghijah from tradition and the less obvious ones of Mansooreh Hosseini, Sadegh Barirani, Koorosh Shishehgaran, and Nosratollah Moslemian, the nostalgic photography of Bahman Jalali and the satiric shots of Shadi Ghadirian, the tangible photos of Kaveh Golestan and the playful images of Hassan Sarbakhshian, the works of Shirin Neshat and Sadegh Tirafkan, the inlaid skull of Andisheh Avini, the cuneiform-covered ewer of Behdad Lahooti, and even multifaceted works such as Ghazaleh Hedayat’s ‘The Sound of My Hair’۱۲.

Some critics find this approach objectionable. They believe that a reason for choosing it is its appeal to Western audiences. However, it seems to have been the only way to create art that would be Iranian and would still have the capacity to be global. This approach was both inevitable and reasonable in that historical situation. Today, contemporary Iranian art is a collection of valuable and memorable works developed through this approach13.

But is this the end of the road for visual arts in Iran? Perhaps not. One can envisage a way by which our visual arts move past the stage of explicitly retelling and representing elements of identity and tradition while being simultaneously contemporary in Iran and the world. I will describe this possible way in the following paragraphs.

Let’s begin with a brief account of Iranian cinema that has purely Iranian elements familiar to all of us while achieving global success. Although cinema is a new form of art and does not allow speaking of a local film tradition14, artistic cinema (or even commercial cinema) always bears signs of its environment. The Iranian popular cinema – known as ‘Film Farsi’ – and intellectual cinema of Iran both attest to this connection. Naturally, in non-commercial Iranian cinema, there has been concerns about being ‘art’, being contemporary and global (e.g. participating in the international festivals), thus obliging filmmakers to choose a specific path. Their choice, too, has more or less been the fourth approach I have mentioned. Most of the prominent Iranian films have represented Iranian elements (and if they did not, they did not attract audiences). Some would look to create a sort of ‘Iranian film’, but even those not preoccupied with national cinema represented Iranian historical, social, and intellectual concerns. Ali Hatami, Bahram Bayzaei, Nasser Taghvaei, Masood Kimiayi, Rakhshan Bani Etemad, and Dariush Mehrjui were among those who took this path, each in their own way15.

Nevertheless, there are examples of works in Iranian cinema that have moved even beyond this stage, gaining a new level of success. In my opinion, the cinema of Abbas Kiarostami is an example of such surpassing. Although in some of Kiarostami’s movies rural Iranian areas are portrayed exotically, his movies do not depend on these places. In other words, Iranian villages are not inseparable parts of his work. The signature of his cinema is its pure form that stems from a personal worldview with features like roads and travelling and even some anti-cinematic characteristics. Most important of all features, in my view, is the director’s indifference. Those are the characteristics of Kiarostami’s cinema, found in almost all of his works. If roads and travels are essential for his movies, we observe them not only in the movies he made in Iran (like ‘Where is the Friend’s Home?’ and ‘And Life Goes On’) but also in the films he made abroad (like ‘Certified Copy’ and the episode he directed in ‘Tickets’). If indifference is an inseparable part of his world, we can see that in every one of his films, even in ‘First Case, Second Case’. In the movies of Kiarostami, even when Iran is not the geographical location, Iran is the place where his mindset is formed. Therefore, a film like ‘Certified Copy’ which lacks any seemingly Iranian elements, is, due to its view toward love, gender, authenticity, and repetition, as Iranian and local as ‘Through the Olive Trees’ and ‘The Wind Will Carry Us’. Take ‘Shirin’ for instance; an anti-cinematic creation whose ingenuity is in the idea (watching the reactions of the audience and not the film). This idea could have been developed by any other artist in any other place who had come up with it. However, even without the narration of the love story of ‘Khosrow and Shirin’, the movie is so much Iranian that it even reminds us of a time when close-ups of actresses were frowned upon by the official censorship (aiming to play down the feminine appeal) and the directors had to justify such takes. We see how Kiarostami has cleverly made a movie entirely made up of a collection of close-up shots of actresses, with each scene having its plausible justification.

Here I do not intend to discuss Kiarostami’s cinema16. I mentioned his films to show that the current state of the other Iranian arts such as painting and sculpture is not necessarily their final stage. They can one day reach a stage where identity is no longer an explicit feature, but an element that is inevitably woven into the work more subtly and smoothly.

Different conditions have led to the thriving of Iranian cinema, conditions that were less available for other forms of art. In Iran, cinema has a good domestic market (especially with the limited exhibitions of foreign films), and private or public investment makes an acceptable turnover. After the Islamic Revolution, in some periods artistic cinema was supported by some government officials. The atmosphere was such that people lined up to purchase tickets for the screening of movies even from directors like Tarkovsky. In addition to the usual Iranian and occasional foreign audiences in festivals, enduring cinematic publications and professional critics appeared from within this vibrancy. Cinema has also the advantage that it has a global grammar (image and editing), thus it gives the movies a potential to become widespread.

So if our contemporary literary works (poems, novels, and plays) have not still found their way into world literature17, one must also consider the issue of language18, even though this is not the only relevant factor. For instance, as mentioned earlier, the fictional prose and storytelling (from Samake Ayyar to Hossein Kord Shabestari and Amir Arsalan) is marginal in our literature compared to the overwhelming centrality of Persian poetry. In addition, fiction writing is a profession in some countries, thus requiring focus and experience on a full-time basis, but these conditions have not existed, and still do not exist, for our novelists. Most importantly, novel writing is based on a modern worldview that has not yet found a deserving status in our society. Even if artists have this vision, their readers are not used to a worldview based on individualism and personal experience leading to pluralism and relativity of discourses19. In short, we have not had any of the hardware or software requirements needed for our works of fiction to flourish on a global scale20.

If we look at the assets available for Iranian cinema compared to the limitations of theater or fiction writing, we might find hope that arts like painting and sculpture will also gradually move past the current stage. In comparison with other forms of art, conditions for the evolution of Iranian visual arts have been met: 1) like cinema, the language of painting and sculpture is common. 2) The number of art students, artists, galleries, and art enthusiasts has significantly grown. 3) Iranian arts like painting and sculpture have, in recent years, found a place however small for themselves in the international scene. 4) Due to the national and international art market, some Iranian artists are full-time professionals. 5) In parallel, related publications have considerably developed and the number of professional critics and experts has also gradually risen. 6) And finally, the intellectual atmosphere within Iran, which, following the Islamic Revolution, had been disrupted in regard to visual arts, is currently changing21. Compared to the decades following the revolution, visual arts are now more commonly considered as progressive, mainstream forms of art. That all does not guarantee anything. But it can provide some hope for a future in which, as a society living on the sidelines of globalization, our visual arts will focus less on presenting manufactured images of identity and tradition and more on portraying our artists’ personal view in the here and now, in a dialogue with other cultures.

Aydin Aghdashloo has an interesting collection of paintings that represent memories of the destruction of our ancient world. In these works, we witness the end of a world. The most interesting pieces for me are those that depict an event, like an antique bowl shattering. In my opinion, one of the beautiful aspects of these works is that, despite the movement that should be inherent to such events, we see no motion at all. As if the painter has masterfully stopped time, or that he has represented a time that is halted. This frozen state of time must be a result of the trauma that we have experienced, as heirs of a deep-rooted culture, by witnessing that incident, the shock of coming face to face with our new situation. We have understood and painted that experience. Now it is time to move past the state of shock and accept the existing reality, thus allowing temporality and movement to return to our view.

[*] This essay would not be written without the thought-provoking conversations with my friend Iman Afsariyan and his concerns about Iranian art in relation to world art. I am very grateful for his helpful remarks. I am also thankful for Hoda Arbabi’s precision that reduced the intricacies of the essay.

The original essay in Persian is published here: Herfe Honarmand, Art Quarterly Magazine, no. 44, winter 2013. The phrases in brackets are added for this translated version.

[1] [Here I do not discuss the relation of Iran’s history to world history, or the historicality of thought and art. About those issues, I have coined the term ‘non-co-historicality’ (na-ham-tarikhi). See: M. Mansur Hashemi, Andishehayi baray aknun (Some Thoughts for the Now), Elm Publications, 2016, pp. 99, 288, 331; “ Moaser budan dar nahamtarikhi” (Being Contemporary in non-co-historicality), Sharestan, Quarterly on architecture and urban design, winter/spring 2016, no. 44-45, pp. 34-7; “Taammol darbareye vaziate nahamtarilhi” (Thinking about the state of non-co-historicality), conversation with Iman Afsaryian, Herfe Honarmand, no. 63, pp. 91-7; “Corbin-e filsoof, tarikhmandi, va Irane moaser” (Corbin the Philosopher, Historicality, and Contemporary Iran), Ayeneye Pajoohesh, 2018, no. 169, pp. 21-30.

[2] As a further example, we can take Alireza Espahbod in place of Mohasses. Although not similar in their work, they both avoided using the Iranian identity.

[3] Those who later tried to make poems based on new Western theories, without enough knowledge of the Persian poetry tradition, did not understand the authenticity of Nima in contrast to the infertility of their project.

[4] See M. Mansur Hashemi, Sadeq Hedayat, Roozgar Publications, 2002, pp. 117-42.

[5] See M. Mansur Hashemi, “Az sug ta shenakht: darbareye Simin Daneshvar va romanhayash” (From lamentation to cognition: on Simin Daneshvar and her novels), Naqd o Barrasiy-e Ketab-e Tehran, no. 32, pp. 52-8. [Also see Andishehayi baraye Aknun, pp. 185-193.]

[6] Interestingly, as well as in our art and literature, we have been forced to make syntheses in our thought and philosophy. The thought of the first modern philosopher in Iran is a synthesis of an interpretation of the theoretical mysticism of Ibn Arabi with a version of Heideggerian philosophy. See M. Mansur Hashemi, Huviyyatandishan va mirath-e fekri-e Ahmad Fardid (Identity-thinkers and the Intellectual Legacy of Ahmad Fardid), Kavir Publications 2004, pp. 75-146. [see also M. Mansur Hashemi, “Fardid Pioneered Post-Bergson Philosophy in Iran”, in Ali Mirsepassi, Iran’s Troubled Modernity, Debating Ahmad Fardid’s Legacy, Cambridge University Press 2019, pp. 265-271; M. Mansur Hashemi, “Iranian Intellectual Confrontation with the Modern West and Modernity”, in The Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Muslim Socio-political Thought, ed. Lutfi Sunar, Routledge 2022, pp. 48-50]. It seems as if from the beginning of modernity till today, we have had no way but to go on that path. A sarcastic example of that combination can be heard in the music of Mohsen Namjoo.

[7] That does not mean that our predecessors ignored visual arts entirely. But comparing our visual heirloom to Western tradition heightens the difference. The visual tradition in the West even gained a religious aspect, reinforcing its impact and prevalence. It is hard to imagine a church without pictures, even in Iran. In the Orthodox Church, discussion about the sacrality of icons became a theological debate (see Amir Nasri, Hekmat-e Shamayelha-ye Masihi, Cheshme publishers 2012). Besides the close relationship of art and religion in the West, since the renaissance, art has been intertwined with sciences, manifested in the anatomical and mechanical drawings of Leonardo Da Vinci, for example. Since long, our predecessors were well aware of the significant tradition of visual arts in the West (e.g. see Himyarῑ, Al-Hoor al-ʿIn, ed. Kamal Mustafa, Tehran 1972, p. 227, who marvels at the expressive portraits by Roman painters). Furthermore, various visual traditions are connected to different world views, with capacities in accord with them. As Master Osman, the character of Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red, says about the different approaches in painting: “Let’s say we were to turn down a street: In a Frankish painting, this would result in our stepping outside both the frame and the painting; in a painting made following the example of the great masters of Herat, it’d bring us to the place from which Allah looks upon us; in a Chinese painting, we’d be trapped, because Chinese illustrations are infinite” (Orhan Pamuk, My Name is Red, trans. Erdağ Göknar, Alfred A. Knopf 2001, Ch. 38). Clearly, the different capacities make different futures for each tradition.

[8] In an exhibition of contemporary miniatures, one showed an addict hunched on the sidewalk. It was meant to depict an unpleasant situation; instead, it looked comical. This kind of ‘defeating the purpose’ results from the different capacities of art forms in representing objects. The success of someone like Farshchian is due, besides his masterful execution, to his understanding of the form and its capacities.

[9] [See M. Mansur Hashemi, “Iranian Intellectual Confrontation with the Modern West and Modernity”, pp. 45-58.]

[10] [Emami wrote articles in the Keyhan International newspaper in the middle of 1960s. See karim Emami on Modern Iranian Culture, Literature and Art, ed. Houra Yavari, compiled by Goli Emami, with an introduction by Shaul Bakhash, Mazda Publishers 2014.]

[11] In a visit to a lithography designs exhibition, Mohammad Fadayi turned my attention to Ardeshir Mohasses borrowing from them.

[12] [For a reading of ‘The sound of my hair’ concerned with the social challenges in the Iranian society, see Hashemi, Andishehayi baray aknun, pp. 563-65.]

[13] Although analyses of contemporary Iranian art still need to be done, some researches have worked in the field. Among them are: Ruyin Pakbaz whose several books are substantial contributions both in introducing modern Western art and in writing a history of contemporary Iranian art; Javad Mojabi with Pishgaman-e Naghashi-ye Moaser-e Iran (nasl-e avval), Honar-e Iran Publications 1998; Tuka Maleki with Honar-e Nogera-ye Iran, Nazar Publications 2011 (which although is written for the teenage audience, is informative for other readers as well). Beside those, magazines like Tandis, Herfe Honarmand, and Honar-e Farda have many articles on different aspects of Iranian contemporary art. Also, some works on Iranian contemporary art are published in European languages. As an example of earlier publications, see Akbar Tadjvidi, L’Art moderne en Iran, Le Ministere Iranien de la Culture et des Arts. For a more recent work, see Different Sames: New Perspectives in Contemporary Iranian Art, ed. Hossein Amirsadeghi, Essays: Hamid Keshmirshekan, Mark Irving, Anthony Downey, Thames & Hudson, London 2009.

[14] The novelty of cinema cannot be compared to the novelty of the works of Ziapoor. He was firstly faced with the long history of Western painting and second with the Iranian visual habits and tradition.

[15] Even developed countries like Japan had no way for introducing their cinema to the world but to create identity-representing art that gained recognition in the West. Ozu, Kurosawa, and Kobayashi had to be first watched in the West to be recognized by us. They had the same problem our artists have: some viewers in their country did not see their work as the real representations of their native culture, making their films more favored abroad than their own homeland.

[16] The movies of Kiarostami address elite intellectual audiences; they attracted philosophers such as Jean-Luc Nancy and Alain Badiou. The natural continuation of the success of Iranian cinema is, for instance, the cinema of Asghar Farhadi who has found a public audience as well because of his proficient story-telling and professional directing.

[17] Let’s not forget the state of Latin American literature that seems to have entered the world arena long ago. But only a few decades back, that literature was involved exactly with this same concern for being read globally. See, for example, Seven Voices, Seven Latin American Writers Talk to Rita Gilbert, First vintage Books edition, New York 1973.

[18] The language of Latin American literature is mainly Spanish. Despite the cultural differences and the distance between the first and third world, it benefits from using a European language with many speakers. There are professional translations of Spanish books into other European languages, especially English. The language of the Indian peninsula that entered the international literature was English too. Also the few Iranian who wrote successful books in European languages (e. g. Fereydoon Hoveyda in Quarantine and Azar Nafisi in reading Lolita in Tehran) had the chance to be read.

[19] A famous Persian translator of Latin American literature, Abdollah Kosari, perceptively points in a conversation to some aspects of the issue. See Siroos Alinejad, Goft-o-goo ba Motarjeman, Agah Publishers 2010, pp. 52-3. [I have discussed the worldview out of which the modern genre of ‘novel’ has emerged here: Sadeq Hedayat, pp. 120-23; and here: Andishehayi baray aknun, pp. 245-61.]

[20] Besides, the market for different arts varies. The market for poetry, for example, is usually local. Many elements get lost in the translation of poems, so translations are not rivals for the Persian poetry. For fiction writers the situation is different. Translations of foreign novels and short stories compete with the native ones, inevitably entering them in an international market.

[21] In contrast to the Identity-thinkers of the previous generation, religious intellectuals who were the most influential thinkers after the Revolution were not familiar with modern literature and arts. See M. Mansur Hashemi, Dinandishan-e Motajadded: Roshanfekri-e dini az Shariati ta Malekian [The Modernist Religion-thinkers: Religious Intellectualism from Shariati to Malekian], Kavir Publications 2006, pp. 211, 224. With the fading of religious intellectualism in Iran, public attention again is directed to continental philosophies, Western arts, and modern novels.

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.