An Introduction to the History of Art and Culture of Iran

Ariasp Dad

It is quite possible that those who have encountered Iranian art have repeatedly asked themselves, especially when compared to works from other cultural domains, why there is almost no depiction here that expresses feelings arising from encounters with evil. Why is it that even the image of a dragon, instead of being terrifying, is rendered in a captivating manner? Or more broadly: why do these works lack the dark, fearsome, and painful aspects of the world? We find such expressions less in various forms of Iranian music as well. One might ask: why do we lack melodies that reflect the turmoil caused by anger or fear in the listener? Why even in religious buildings, whose function should emphasize the grandeur of God and the supremacy of divine intermediaries, is the state of awe absent, unlike in European cathedrals?

On the other hand, why did the idea of the transcendence of the Absolute not take hold to the extent that it led to the elimination of any kind of imagery? And if the visual culture continued, one might ask why Iranian Muslim painters had no inclination to illustrate their religious texts. Why did they confine themselves to depicting scenes of the Prophet’s spiritual ascension, mostly through the lens of a chapter from Nezami’s romantic Khamsa, or the Golestan? Or why, even in works like the Khaqani-nama, is Imam Ali, the first Shia Imam, depicted as a hero?

Why, in the depiction of military victories, which reached its peak during the Sassanian era, is there a tendency to emphasize the symbolic generosity and grandeur of the sovereign rather than the destruction of the enemy and boasting about conquering other lands, as seen in the motifs of the Assyrians, Romans, and others?

Similarly, there is no focus on capturing fleeting moments or emptying the mind to follow the immediate flow of events, as we find in ink wash painting or haiku poetry.

To find the answer, it is necessary to continue the discussions along the path we have taken so far.

Given what has been discussed in previous essays about defining general concepts, we once again draw the readers’ attention to the notion that intellectual and artistic schools emerge within a “cosmology.” When we look at the historical trajectory of culture, we can identify various schools of each culture under the overarching cultural cosmology from which they arose.

To better understand our concept of “cosmology” as the fertile ground from which styles and schools emerge, consider how, within the Greco-Roman cosmology, the evolution of the classical school led to the emergence of the Romanesque style. From this historical progression, the Gothic school was born, and Romanticism eventually emerged from it. All these are branches that grew from the same initial core, with each new growth adding a fresh twist to the body of this cosmology, making it more robust.

Therefore, in examining schools, it is crucial to recognize how each school inherits characteristics and features from the cosmology under which it flourished. These traits function as a shared spirit within the seemingly diverse manifestations of each cultural nucleus.

In these motifs, the power of the Shahanshah is typically depicted through displays of heroism and symbolic generosity. In the relief at Darabgird, which narrates the victory of Shapur I over the Roman emperors, other details are also noteworthy. The Roman dignitaries are all depicted with the same appearance and arrangement, while the Iranian nobles and generals behind Shapur are each portrayed with distinct features, each group wearing different types of clothing and hats. The concept of power in Iran, continuing the Persian tradition, is based on the diversity of cultures under the banner of the Shahanshah and considers this diversity a source of pride.

As mentioned in previous discussions, within each cultural nucleus, concepts and ideas gradually formed around fundamental subjects—ontology, anthropology, and chronology—over millennia, creating a unique spirit. Although this spirit evolves over time and may be influenced by others, it continues to grow on its own ground as long as it is alive. It stands on its initial foundational roots, and continues to develop, assimilate, and transform.

To better understand cultural cosmologies and compare the underlying patterns and functions of each nucleus, one can identify characteristics that make it possible to comprehend actions, beliefs, social systems, and artistic creation within each one. It should be noted, however, that none of the characteristics of human societies are completely distinct from others, and it is possible to find traces of the traits we describe in other places and among other cultures as well.

With this explanation, what distinguishes a cultural cosmology is the extensive and interconnected network that revolves around the fundamental idea of that culture in understanding various aspects of existence. In the modern era, gaining such understanding and naming these underlying patterns is only possible through comparison with others, and through observing and evaluating differences. Thus, we first take a general look at other cultural nuclei and the spirit that permeates their art and culture, especially examining the “creation myths” that reveal the oldest core ideas of each culture:

The spirit of Chinese art and its cultural satellites has cultivated a unique narrative of existence as a labyrinthine, “ineffable” experience. Within the architectural spaces, the gardens created under this cosmology, as well as in scroll paintings, sculptures, and music, one finds oneself as a mere particle immersed in an endless, boundless current. This world of boundlessness and its “unnameable” essence pulse with the fleeting moments of time. This flowing spirit resembles the torrents of rushing rivers, the endless stillness of mountains, and the vitality of ancient trees; it stretches like an unfurling scroll into infinity, immersed in the tempestuous turmoil of storms or subsumed in the endless silence of nature. The role of humanity is to contemplate and absorb this ongoing flow, and to follow its inherent order.

In the formation of the early cores of culture in the agrarian life of this land, an understanding of existence gradually emerged, viewing life as a daily struggle.

Creation myths here were understood as a cosmic battle extending across the universe and throughout time. Through the choice of goodness, by means of cultivation and the application of wisdom, humans could align themselves with the support of Ahura Mazda.

This struggle initially took the form of a conflict between water, fertility, and prosperity on one side, and the Ahrimanic forces of dryness, barrenness, and destruction on the other.

However, this idea did not stop there; it evolved into the ideal of manifesting the beautiful nature of the world, giving rise to ethics, values, and art.

Here, the term “epic” does not refer to a culture of warfare. The nomadic or border-dwelling peoples in the Zagros, the valley of Quchan, the Khyber Pass, the Caucasus, and so on were indeed very courageous and battle-tested due to their circumstances. However, these traits are not evident in the central regions.

The concept of heroism, as referred to here, was pervasive and creative among all these people. It is likely that, due to more opportunities in regions distant from direct conflict, this idea appeared in various vibrant forms across different schools of thought.

Ancient culture carries the idea of the proliferation of the divine through words; words contain a thousand and one names of the deity that, while revealing themselves in their creations, remain hidden in essence. The creation story begins with Adam’s sin and his fall to earth. The spirit of art and culture in this tradition involves the remembrance of the names of God, the lamentation of sin, separation from the origin, seeking forgiveness, and the desire to return to Him. In this cosmology, “sin” and “prophecy” are key concepts organizing the system of consciousness.

The spirit of art in the Indian subcontinent embodies an eternal meditation within the cosmic play of Brahma; a dynamic, trembling, and colorful scene, akin to a rhythm that continuously multiplies and returns to its origin. From this cosmology, the Mahabharata, with its two hundred thousand verses (about eight times the length of Homer’s works), was created, making it the longest and most voluminous epic in the world.

However, in the functions and art of the subcontinent, there is little indication of an epic spirit; it seems that this spirit is embodied solely in a narrative of the cosmic realm. Underneath the creation, which itself is the result of Brahma’s cosmic play, we are actors in roles written within the cosmic world; like a dancer playing the role of Ganesha or Shiva, or a musician whose voice represents the rhythm of Brahma’s wheel.

The spirit of Western art (Greek, Roman, and Germanic) has manifested in a dramatic tragic form; a tragedy as vast as the world, spanning from creation to eternity. Aside from specific cases 1 (such as the Germanic peoples’ experience during the formation of a national identity), the prevailing spirit in Western art heritage—evident in novels, painting, sculpture, music, and theater, from Greek works through the rich Christian era to Romanticism—is tragic.

The creation of numerous artworks that depict the sufferings of Christ, which constitute a significant portion of Western art, and even the development of genres like still life or self-portraiture, have been shaped and given meaning within this same tragic spirit. Notably, Christianity only exhibits this tragic quality within its European branch.

The essence of Iranian culture can be described as “epic”; and under this concept, one can better understand the various aspects of its thought, ethics, art, and social functions. The term “epic,” which is more commonly associated with a literary genre, is used here to convey a much broader meaning. This meaning will be gradually explained in the continuation of this discussion and in future discussions.

To follow the path of understanding the epic nature of this culture, from the battle between cultivation and destruction and aridity, and the effort to manifest the beautiful spirit of the world, one can once again look at the countless vegetal motifs that have emerged under this tradition.

The intricate vine patterns that emerge from a central medallion and spread across the surface of buildings or carpets have permeated everywhere, rhythmically covering the space. These patterns represent the realization of the idea of spreading the seeds of prosperity, the growth and fruitfulness of rituals, and the triumph of culture in the world.

It should be noted that the Iranian cosmological tradition is one of the fundamental cultural characteristics of Iranians, and indeed, it is the oldest and most enduring of them. Over the course of history, elements of the ancient cosmological tradition, as well as Greek-Roman thought, were integrated into the Iranian cosmology. These intertwined threads continued to evolve with their ups and downs up to the modern era, when a new chapter began in the encounter with modern culture.

In the formation of the core of Iranian culture, this epic spirit was the product of an inherent quality in the agrarian life of the land, which, with its unique conditions, developed over millennia and flourished through challenges posed by the natural environment and interactions with other cultures. This spirit gradually shaped an understanding of existence that viewed life as a daily struggle. In this worldview, the creation story was conceived as a cosmic battle spanning the universe and time. By choosing goodness and applying wisdom, humans could align themselves with the support of Ahura Mazda.

This struggle initially took the form of a conflict between water, fertility, and prosperity on one side, and Ahrimanic forces of dryness, barrenness, and destruction on the other. However, this idea did not end there; it evolved and expanded into an ideal of striving to cultivate the world and beautify the universe. From this ideal emerged ethics, values, and art.

The Iranian cosmology is the result of weaving together various strands—from ideas to ethics, rituals, art, and the organization of life—around the initial epic concept of agrarian heroism, which has been layered and interwoven throughout a long history. Over time, with the addition of other influences to the Iranians, and through everything that happened to this culture—what was added or gradually refined and reduced—this epic thread remained strong. It evolved into much more complex forms than its original state, bearing new fruits on fresh branches.

Jalal Khalighi Motlaq points out that, according to Maurice Bowra’s research, the introduction of a new religion usually marks the beginning of the decline of epic poetry. He also identifies social and historical causes, such as foreign invasions or religious movements, and cultural infiltration from outside, as factors in the fading of epic verses. For example, he refers to epic poetry among the Anglo-Saxons, which survived at least until the death of Edward the Confessor (in 1066 CE). With the victory of the Normans, who spoke a foreign language and had their own poetry, the Anglo-Saxon epic tradition was so thoroughly destroyed that no trace of it remained. 2

In the design schools within the Iranian cosmology, what we call the epic spirit is manifested in the attention given to various expressions of “light.” Light, besides being one of the four fundamental elements of the universe, has a special significance in its struggle against and triumph over darkness. Light is considered a symbol of “wisdom,” the highest gift and the greatest weapon of humanity in its battle across the cosmos.

Accordingly, the “sunburst” is a highly esteemed motif and, in line with its meaning in the arts, is used in a variety of forms. On the frontispiece of valuable manuscripts, the sunburst represents the dawn of the sun of knowledge and the radiance of wisdom. Typically, the elaborate decoration of the initial sunburst emphasizes the importance of the manuscript.

Similarly, the sun motif at the apex of the iwan of Iranian mosques symbolizes the dawn of the sun and the unfolding canopy of its light. The stars designed beneath the muqarnas of the iwan signify the radiance of light emerging from this threshold into the darkness.

However, the history of Iranian art and culture has had a different fate. What Bowra calls “cultural infiltration by foreigners,” along with factors such as “the emergence of hybrid ideas” and “the introduction of a new religion,” did not extinguish the epic spirit. Even with the emergence of significant obstacles such as Ash’ari thought, the epic thread in Iranian culture continued robustly, albeit in new forms. It is common for Iranologists to cite the Persian language as the primary reason for the continuity of this culture. However, from a broader perspective, the survival of the overarching spirit of the art and cultural framework, which has been grounded in an epic context, has facilitated this continuity. The revival of Persian literature is merely one of the signs of this enduring legacy.

The goal of these explanations is not to arrive at a definition of a static and unchanging core. What we are attempting to approach is the spiritual constellation of a historical nation, which, over a long period, has experienced a diverse range of events and circumstances. Accordingly, we observe a variety of manifestations of this spirit in different eras, ranging from agrarian epic heroism to the ethos of chivalry and the development of a sense of wisdom.

Thus, it is evident that the subject is far removed from mere martial valor. For example, the thoughts of Omar Khayyam and, following him, Hafez, which, in the midst of tension and experiences of defeat and destruction, focus on the present moment and celebrate joy and happiness, reflect a dimension of this spirit as a form of resistance against rigidity and an insistence on wisdom suited to the circumstances. This demonstrates a long journey through the millennia, from confronting fertility with barrenness to arriving at these more complex forms of interaction.

In the dawn of history, this perspective on existence, with a very ancient background, had developed to the point where it established the foundations of a grand system and culminated in the formation of the Achaemenid Empire within the framework of the Iranian cultural constellation. The first school of Iranian art and culture, known as the “Persian School” or “School of Parsism,” emerged from within this framework. This establishment marked the beginning of a long journey, which saw subsequent manifestations in the Parthian School during the Parthian era, and in the revival of Iranian culture (in the 9th and 10th centuries CE) through the Khorasan School. It continued through successive transformations in the styles of Razi, Azari, and Isfahan, revealing new forms over time.

Moreover, throughout history, we observe various manifestations of this spirit in architectural design, in the expansive realm of Persian literature, and in the creation of meaningful rituals that shape the daily lives of people, as well as in the rich traditions of melodies and music within this culture.

In the design of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque’s dome chamber, we witness the pinnacle of light manipulation in Iranian architecture. The motif of the Simurgh, which is the essence of this cultural constellation, appears beneath the dome with the light streaming from the east (the direction of enlightenment). The rays that pass through the latticework of the dome are engineered in such a way that the resulting patches of light do not cast shadows of the window lattice but rather project the image of the Sun itself into the darkness of the building’s interior.

One of the challenges in utilizing terms that have already acquired independent meanings is the difficulty of their adaptation. Naming is stepping onto the threshold of concepts, and establishing terms makes understanding possible; by naming, we create a relationship between our current state of awareness and the world we inhabit. Words, carrying the layered meanings accumulated over time, serve as the memory of the evolution of awareness in each historical language.

In contemporary scholarship, the term “epic” is used to describe a specific literary genre. However, in this context, we use the term “epic” to denote the fourth layer within the Iranian cultural framework. This is intended to shed light on the connection between form, idea, and content at a deeper level of art and cultural history. As previously mentioned, the fourth layer is what differentiates each cultural system from others, providing it with distinction and character. We aim to use the term “epic” to help identify and differentiate works created within this particular understanding of existence from those produced in other cultural worlds.

Thus, it is clear that our use of the term “epic” extends far beyond the literary genre where it is typically manifested. In this proposed application, the essence of the Iranian cultural framework is “epic” in its entirety—encompassing historical structure, political thought, and individual and collective expressions. The core understanding of the world’s creation, the concept of the nation, the formation of cultural communities, and the foundation of diverse and complex duties within the historical-cultural geography of Iran are all considered “epic.” Ultimately, the epic spirit represents the essence of Iranian art.

The essence that we call “epic” cannot develop in an environment devoid of constant challenges in managing life and engaging in intellectual endeavors. Therefore, it is essential to consider the historical contexts in which this culture grew, particularly its interactions and conflicts with other centers of thought.

“Today, there is still a tradition in parts of the world where a form of storytelling is prevalent that often describes the remarkable deeds of renowned men in verse. In these stories, the primary focus is on the element of wonder and astonishment. However, the themes of heroism or even human virtues, which occasionally play a role in the stories, are given much less importance.”

In this form of storytelling, the actual behavior of a hero, which would lead listeners to praise the human virtues of the hero, is not seen. This art of storytelling is relatively more primitive and prefers any trials that transcend the ordinary human condition through magical or supernatural means.

Various examples of such stories can be found among the Finns, the Altai Tatars, in Abakan (the capital of the Cherkess lands), the Chalka Mongols, Tibetans, and in Brno. These stories follow a perspective in which humans are not at the center of creation but are instead imprisoned among numerous invisible influences and forces. Therefore, the main effort of the hero is to overcome obstacles by finding solutions—though imaginary—that cannot be achieved merely through human gifts alone.

In this context, a great man is not someone who makes the best use of his personal abilities but rather someone who harnesses supernatural forces to his advantage. Although renowned heroes in Homeric epics, Beowulf, and more so in the less ornate epics of the Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Ase, Kalmyks, or Khotons sometimes resort to such methods, in primitive societies, utilizing supernatural and foreign forces to one’s advantage is the ultimate goal. This naturally reflects a different conception within these societies about the nature and potential of humanity and its place in the world. In such societies, although the characters in the stories are not unaware of or uninterested in fame or disgrace, and even desire it, fame and disgrace are not their highest goals. This is the distinction between shamanic epics and true epics.” 3

Professor Khalaghi Motlagh, analyzing Bura’s theories, points to a parallel in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. In the epic sections of the Shahnameh, the hero does not use magical forces to defeat demons and sorcerers—who play significant roles in stories like the Seven Labors of Rustam and the Tale of Akhavan-e Div—but relies instead on physical strength, wisdom, and skill. The key point here is the evolution from a narrative framework centered around “magic” to one centered on “human agency.”

In general, as previously mentioned, the geographical location of the founding centers has been one of the influential factors in shaping their diverse characteristics; this important factor has also been decisive in the development and flourishing of the epic spirit. The more a center is located on the periphery of the ancient world, the more it has established its own order in a state of non-conflict with others. For instance, in the cultural sphere of China, the seeds of epic thought can be found in the very ancient myths of the land, which gradually faded with the dominance of the spiritual realm of Daoism. A similar fate has befallen the Indian subcontinent and ancient cultures, each for its own specific reasons.

The continuity of life on the Iranian plateau, whose civilization was based on agrarian existence, not only required significant effort and management of nature due to its climatic conditions but also gave these epic elements depth due to its unique geographical position in constant interaction with neighboring cultural regions.

As we delve into history and the formation of the Persian school of thought, the interaction with other intellectual centers and the “debate of ideas,” as well as the mutual influence and impact, become significant. One of the most notable of these interactions and exchanges of intellectual systems is the relationship between Iranian thought and the Greco-Roman system. During the formation of the Persian school and the Achaemenid Empire, pre-Socratic Greek philosophers such as Heraclitus were influenced by Iranian ideas. Reports from some Greek writers, such as Ctesias, Herodotus, Xenophon, and Strabo, indicate the popularity of Iranian epic songs and narratives among the Greeks during the Median and Achaemenid periods. Although the original form of these epics has not survived, evidence from scholars like Jalal Khaleghi-Motlagh suggests that Xenophon’s Cyropaedia was based on Iranian written sources, and this literary type continued in Iranian culture under the name “Karnamak.”

13th century CE / 7th century AH

“The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi is considered the most authentic type of epic, because although in the Shahnameh everything happens according to the will of God, and the great heroes are all worshippers of God and monotheists, attributing their victories to the will of the deities, God’s role is not as overt as in Homer’s epics. In the Shahnameh, God does not participate directly in events but rather holds the threads behind the scenes. Therefore, stories like those of Rostam and Sohrab, and Esfandiyar, should be considered among the most epic of epic stories in the world.”

“In Iran, many heroic elements from the Avesta have made their way into the Parthian epics, and many elements from the Shahnameh have been incorporated into later epics, including religious and historical epics, up to the Qaisarnameh by the poet Peshawari. Elements of the Shahnameh can be observed in historical works (such as the ‘Al-Sudur’ by Rawandi), mystical writings (including the works of Sheikh Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi, Attar, and Rumi), ethical literature (such as Saadi’s ‘Bustān’ and ‘Gulistān’), lyric poetry (such as Hafiz’s ghazals), legendary works (such as the ‘Kalila wa Dimna’ by Qanai Tusi), and satirical social literature (such as ‘The Mouse and the Cat’ by Obeyd Zakani).”

Khalighi-Motlagh, Jalal (2007)

We begin with the formation of epic narratives in this culture:

Research into epic poetry in human heritage shows that the seeds of epic thought exist in many centers and among many peoples, but each has followed a different historical trajectory.

As research by Maurice Bowra and Jalaal Khaleghi-Motlagh, as noted in his commentaries, indicates, not all war narratives contain the essence of epic literature. For instance, the surviving war stories among Arabs and some peoples of Mesopotamia and Africa are often more akin to ‘razz’ chants among warrior tribes and rivals. The fate of this epic nature has also varied in different contexts; for example, among the Germanic and Mediterranean peoples, with the initial rays of Christianity, this nature retreated into the depths of history. Christian faith could not drive the wheel of these epics; as Henry Corbin states, Christians with their new faith lacked the power to turn the wheel of epic.

As Khaleghi-Motlagh points out: “In any case, for various reasons, some peoples do not have epics and their works have not gone beyond panegyrics and elegies. It seems that the intellectual effort necessary for such advancement was beyond their capacity.

The Chinese had the seeds of epic, but they did not cultivate or harvest it. Perhaps the great spiritual force that dominated Chinese culture was incompatible with the world of heroism, unrestrained individualism, and self-confidence. The same can be said for the Israelites, who have panegyrics and elegies but no epic poetry. The Russians did not achieve epic storytelling; instead, they have only epic songs. One such example is the lyrical epic piece of Igor’s Campaign, which was likely composed in Old Russian poetry at the end of the 12th century.”

The texts of the Persian school, which result from a confluence of agricultural life experiences and the formation of the concept of royal power, can be regarded as a kind of epic advisory literature for people of other lands and times. These texts serve as ethical guides emphasizing the values of loyalty, chivalry, and the nobility of spirit and the eternal respect for life and the soul.

The inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire were not only carved into rocks but also reproduced on more perishable materials and sent throughout the empire and the contemporary world. 4 These fragments, including examples like the Cyrus Cylinder, mark the beginning of the genre of divine inscriptions, which would later evolve into the invaluable epic traditions, including the work of Hakim Tusi. There are similarities between these ancient writings and the prologues of stories and royal admonitions found in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh during coronation ceremonies.

Like the Behistun Inscription, the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi is not merely a description of the battlefield; the depiction of battles in the Shahnameh is always brief. The bulk of this work is philosophical; it encompasses the philosophy of life, the honorable way of living and dying, and the chronicle of customs and manners. It chronicles the history of a nation and its human endeavor in confronting existence and understanding its norms. The spirit of these texts differs from the Mesopotamian inscriptions, which primarily detail conquests, the downfall of cities, punishment of wrongdoers, and legal codes.

In the cultural realm that would later be known as Greece, we encounter written epic literature that describes the battles between the heroes of different cities. These stories were shaped by the essence of this culture’s understanding of existence, humanity, and time. Therefore, they were rooted in the same cosmology and the relationship between humans and the “lords of species.” In this way, Greek epic literature can be seen as a narrative of battles that continued the work and mythical characteristics of their worldview.

At the beginning of the decline of national states in Iran and the cultural weakening, a movement emerged to renew the Persian epic narratives. Among all these efforts, the Shahnameh by Hakim Tusi 5 gained significant popularity as a versified wisdom book, and the spread of Shahnameh recitations in public spaces became one of the factors reinforcing national unity among Iranians. Only about thirty years after the composition of the Shahnameh, Qatran Tabrizi was reciting it in Azerbaijan and highly valuing it. This work was composed in Khorasan but quickly spread to Lorestan and among the people of Western Iran beyond the Zagros Mountains. This expansion and influence were not confined to epic literature and the history of Iranian battles—Nizami Ganjavi, as he himself noted, drew inspiration from the Shahnameh to recompose romantic narratives, depicting a more complex dimension of epic thought in these stories. Similarly, Attar Neyshabouri continued this tradition, refreshing the “spiritual journey of the Iranian soul” in the story of Simorgh, and Sheikh Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi, revisiting the heritage of Iranian thought, established a new philosophical system in the form of a mystical epic.

This cultural movement based on epic thought in the Iranian world also spread to other languages besides Persian. For instance, shortly after, Shota Rustaveli composed the epic The Knight in the Panther’s Skin in Georgian, influenced by Ferdowsi. In Armenian literature, the epic David of Sasun was written. Bandari of Isfahan translated the Shahnameh into Arabic, and, in the same tradition but at a later date, Mukhtum Quli created a work for the Turks of Khorasan. In this work, the themes and names of characters were adapted to reflect Islamic stories, in line with the newly converted Turks who had integrated into the Iranian cultural sphere.

The Shahnameh, although a novel and exalted work in its time, and Ferdowsi’s great achievement was that “he composed a work for the future of Iran,” should be remembered as a creation based on earlier divine scriptures and rewritten works from the Parthian and Sassanian eras. As evidenced by some texts in the Yashts and the ancient Avesta, the tradition of composing divine epics during the Parthian period had its roots in older writings. Ferdowsi was a continuer of this tradition of renewing ancient sources; a tradition where, by reviving knowledge accumulated from the past—from the foundations of the Achaemenid era to later sources—each period updated the ancient heritage according to the evolution of thought. This tradition has left us a collection of heroic, romantic epics, and wisdom literature of the Khosrowan, each representing a renewal of ancient ideas in their time—from the Yashts to the epics of Zariran, Vis and Ramin, Bijan and Manijeh, Garshaspnameh, and others.

“If the Iliad of Homer begins with ‘Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles,’ the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi begins with praise of its central themes: ‘In the name of God, the Lord of soul and wisdom / Beyond whom no thought can pass.’ The introduction of the Shahnameh bears a close resemblance to the beginning of the Achaemenid inscriptions. The phrase ‘God of soul and wisdom’ is a precise translation of the Old Persian term ‘Ahura Mazda,’ meaning ‘the thinking existence’ (Ahura Mazda = Aḥ + man + zada; ‘Aḥ’ from the root ‘to be,’ and ‘man’ or ‘minu’ is good thought, as in Vohumana).”6

“In epic poetry, ‘conflict’ and ‘confrontation’ are among the most important aspects of understanding the work. However, the site of this conflict may sometimes be between an individual and themselves, sometimes it is the arena of ideas where individuals clash with each other. Sometimes the battleground is between the individual and the world, as seen in the story of Sohrab, and at other times, it is an inner conflict between reason and fate, as in the story of Siyavash in Turan. Unlike Sohrab, Siyavash is aware of his fate; the hero knowingly and consciously meets the disaster that awaits him.

These narratives and stories are distinguished not because they are the creation of a single poet, but because they are the natural products of the cultural psyche of Iranians, shaped and refined over centuries.”

Ferdowsi, by distancing himself from the heritage of the past and having endured crises and ruptures that placed him in contrast with ancient stories, offered a renewed narrative of an era that had been experienced and left behind. Through reworking and reviving the memories of struggles, efforts, and customs, the poet created a contemporary and enduring record.

Although some scholars do not consider epic poetry as part of ‘history,’ it should be noted that the narratives of the Shahnameh, which emerged from the historical and social context of this land, were regarded as the historical account of Iran in their time.

Note that Persian epic literature has fundamental differences from epic narratives in other cultural centers, including:

- Persian epic has a national character and is not about the conflicts between tribes and peoples.

- Heroes rise to battle with ideals of divine glory.

- It is different from sacred texts, including Hindu epic texts such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Upanishads, which are based on cosmic characteristics and narrated through allegorical forms. In Persian epic, the focus is not on divine struggles or interventions of supernatural forces. The stories unfold on Earth among heroes with human qualities.

- In Persian epic poetry, battles are not motivated by religious or racial reasons (in the contemporary sense, meaning bloodline or race). Instead, they are filled with references to the value of wisdom and life. Therefore, the identity of heroes in Persian epics is not defined by tribal or ethnic affiliations. For example, many of them trace their lineage back to the non-Iranians; the great hero Rostam has a maternal lineage to Zahhak, and Kay Khosrow to the daughter of Afrasiab of Turan.

- Persian epic narratives are manifested in the historical territorial realm that intertwines with the fate of the Iranian people and reflects their existence and spirit within this context. In their consciousness, this land is situated within the “Seven Climes” of the ancient world.

The concept of the “Seven Climates” in the history of Iranian thought refers to both a geographic and celestial dimension, as well as a spiritual one. Its earliest roots appear as “Seven Countries” in ancient Persian cosmology. In parallel, the Parthian system, based on the Seven Spahbedan, emerged as the most enduring political and cultural power structure in Iran. This system persisted strongly throughout much of the region until the 11th century CE and continued even longer in areas such as Deylam, Tabaristan, Arran, Shervan, and Armenia.

Henry Corbin, who recognized the continuity of Iranian intellectual traditions, offers this interpretation of the spiritual aspect of the concept:

“Seven circles with equal diameters are arranged, with the central circle representing the central climate. Surrounding it are six circles that touch each other, representing the other six climates. Unlike contemporary maps, this system of seven countries has no fixed coordinates or permanent locations. Instead, it functions more like a mandala, an idealized geography. We can imagine a vertical axis passing through the center of the central climate and shift the eastern regions to align with the western ones. Thus, all sacred locations in the eastern climate can be mirrored and recognized in the western climate.”

In this view, the earthly place itself is not sacred by virtue of being a place, but rather it is the soul that imbues places with sanctity, transforming them into sacred spaces. Dreams and visions provide the context for narratives in which the soul reveals its past and future to itself.

In this narrative, there is no place designated as a “sacred site” that naturally embodies the spirit of the inhabitants. Consequently, the story model shifts from the hero’s departure from and return to a sacred land. Instead, the concept of a “special place” manifests in the form of a “garden,” where the four fundamental elements of existence—water, air, earth, and fire (light)—are directly present. Under the Iranian idealized geography of the seven regions, the garden symbolizes the heavenly realm or the “eighth region,” which is realized on earth through human struggle against obstacles. This struggle renders the garden a heroic realm. Gardens represent the fruition of heroic wisdom, illuminated by the light of divine grace; they are spaces where dialogue and empathy become possible. As defined, the garden is a bounded territory where new plans are devised through effort, linking the concept of “country” with the garden.

One of the most prominent manifestations of epic thought in the arts is the theme of the “garden.” The garden is the fruit of toil and the reflection of the historical spirit of peoples who possessed a determined will to transform the world. This will was driven by a desire for prosperity and the cultivation of the world’s noble essence.

In Iranian art, the geometric design of the garden, the motif of the cypress tree, intricate plants, rosettes, blooming flowers, and enamored birds gradually developed over the ages, manifesting in countless ways across all forms of art. In the forthcoming discussions, we will delve into the subject of the Iranian garden in detail. Here, we draw readers’ attention to the significance of garden design, one of the oldest manifestations of art in this cultural framework, and one that has persisted from the Persian tradition to modern times.

It is important to note that the Iranian garden design is not merely a spatial arrangement within the natural landscape. Rather, it is a form through which an idea and content are expressed. We find the role of the garden everywhere: on book covers, in the decorative patterns of manuscript pages, in carpets depicting small gardens spread across interior spaces, and in the designs of tablecloths, curtains, stucco work, stone carving, and the patterned tiles of Iranian mosques’ domes, iwans, and walls.

The attention to the correspondence between this historical and ideal geography and the ontological idea of the divine entities (Amshaspands) also illuminates another fundamental aspect of this thought. Just as the seven regions, akin to the Amshaspands, have a central place representing the divine wisdom of Ahura Mazda and human intellect, the other six regions surround this central core.

The cultural-historical life of the people spiritually united within this ideal geography gave rise to another esteemed concept: the “Eighth Region.” The Eighth Region represents the manifestation of the light of awareness or “Khorneh.” In the mystical thought of Sheikh Ishraq, it is referred to as “Khurrah,” with the Arabic term “Sakinah” (meaning peaceful abode) used for this concept in his writings.

Sheikh Ishraq considers “Khurrah” to be pure spiritual light that dwells in the “soul,” transforming it into a “radiant body,” similar to how, in Iranian thought, “Khorneh” (or “Farrah”) signifies the divine light of glory residing in the soul of the noble king or hero.

This angelology differs from other intellectual traditions; the Amshaspands, in this thought, have a physical and tangible existence beyond their ideal and divine form. The garden (Bagh) is the embodiment of the Amshaspands and represents the realization of the Eighth Region.

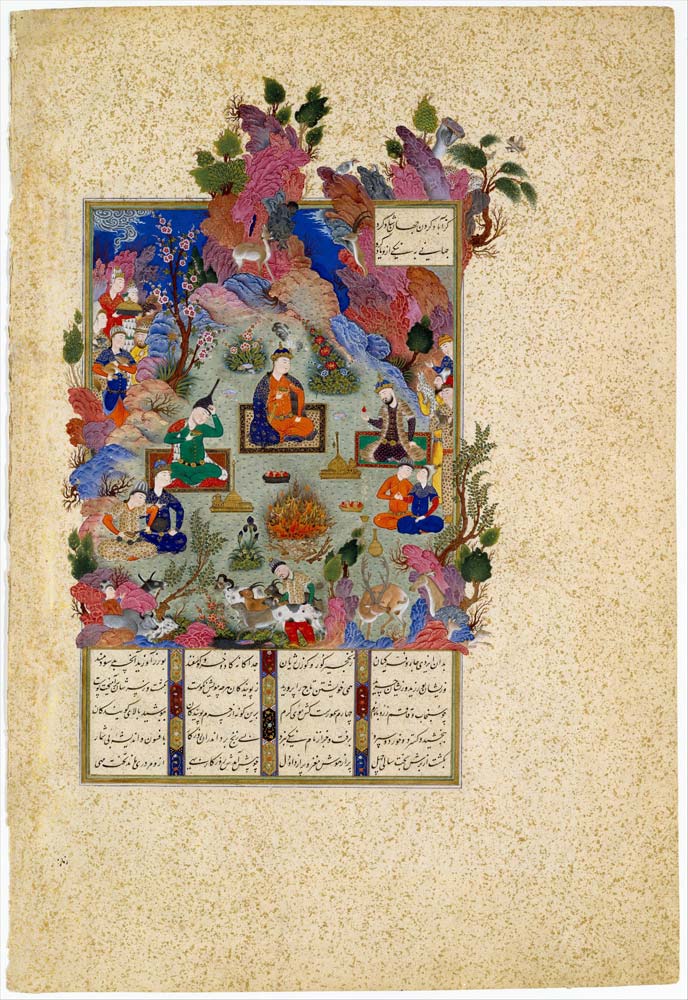

According to statistics from major libraries in Iran and abroad, there are approximately fourteen thousand images related to Shahnameh manuscripts preserved in books, paintings, or lithographs.7 The second highest number of images pertains to Nezami’s Khamsa, which includes the most important romantic epics of this culture. Other subjects are significantly scattered and few in number. Among the most important and frequently depicted scenes are those with religious themes, such as the Prophet Muhammad’s ascension (Mi’raj), which are predominantly illustrated in the context of Nezami’s depiction of the Mi’raj in the introduction to Khosrow and Shirin. The emphasis on the epic aspects in religious narratives can also be observed in examples like Khawarannameh.

It is known that in the structure of ancient Iranian armies, the use of music and large wind instruments was prevalent. Aside from the physical remnants of these instruments, historians like Procopius of Caesarea have left descriptions of their performances. This type of music was distinctly martial and, in the general sense of the term, overtly epic.

At the same time, examining the repertoire of Iranian music, from that performed in urban events and ceremonies—such as the music of the Naqqareh khaneh (drum houses)—to the classical music of the Qajar period, and regional music including the Klam and Tanbur of the Kermanshah, the vocal and dotar traditions of Khorasan, the Baluchi musicians, and the Ashiqs of Azerbaijan, and the music of Ta’ziyeh (passion plays), reveals that the predominant themes and forms in these musical expressions are epic in nature (which will be explored in detail in future discussions).

In the Iranian epic tradition, the essence of epic thought extends beyond literary narratives and arts, permeating social ethics and ultimately becoming embedded in the “customs” of historical Iranian society. In this culture, figures such as young heroes, doughty men, and mystics are not just descriptions of individuals but reflect ancient thematic structures around which certain social frameworks have been formed according to the era and historical conditions. Even in jurisprudential terminology, a scholar who holds the position of Ijtihad (independent legal reasoning) refers to their reasoned opinion, which involves assuming responsibility, as a “fatwa” (edict).

Researchers have correctly noted the connection between the roots of chivalry and the rituals of zourkhaneh (traditional Iranian gymnasiums) with the ancient Mithraic rites. 8

At a crucial historical juncture, these ancient rites of chivalry contributed to the establishment of a civil system, relying on chivalry and moral values to ensure security in the absence of national states. Historical events reveal that the establishment of zourkhanehs and the joining of men into chivalric circles with hierarchical structures 9 coincided with the invasions of nomadic tribes and the devastation of the Mongols 10 —after the fall of national states, in a period where conquering forces lacked the motivation and will to safeguard the lives, property, and honor of the people. In this new form, drawing upon some very ancient models of architecture, music, poetry, and physical training, a mechanism for protecting the lives, property, and security of city-dwellers was created. The strength of these circles lay in their connection to the broader traditions, ethical patterns, and chivalric values within the cultural ethos.

Illustration by Sultan Muhammad, 16th Century / 10th Hijri

Among religious narratives, the most significant images are related to the Ascension (Mi’raj) of the Prophet Muhammad. The epic dimension of the Ascension, which involves the narrative of the soul’s journey to the highest realms and its subsequent self-sacrifice in returning to aid others, has been of great interest among Iranians. Ascension narratives have been crafted around this theme, such as:

“Once again, from the angelic realm I shall rise, / What is beyond imagination, I shall behold.”

(Maulavi, Rumi)

In foundational civilizations, it is common for an ideological system with religious overtones, embodying the spirit of the culture, to play a role in defining identity. Examples include: Daoism in China, Hinduism in the Indian subcontinent, Abrahamic religions in the ancient tradition, and Roman paganism followed by Christianity in the European world.

In the Iranian cultural system, the relationship with religion is distinct in several ways. To this day, scholars of Iranian studies have not found conclusive evidence clearly indicating what the official religion was during the Achaemenid era. Research into later periods reveals the existence of multiple simultaneous religions and cults that coexisted and persisted over extended periods. This extensive list includes Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, Manichaeism, Judaism, Christianity in the western Achaemenid empire, Buddhism in the east, and Islam, each of which played a significant role or was dominant in various eras. From this perspective, the strongest thread that has endured over time and served as a factor of connection, continuity, and unity among the diverse ethnic, religious, and racial groups of Iranians has not been a single religion, but rather what we might call a heroic spirit in the context of discourse.

In tragedy, the primary role falls upon “Moira,” ۱۱ or fate and destiny. From a tragic perspective, the confrontation between characters like Antigone and Creon is not understood as a moral versus immoral conflict but rather as the result of a dire fate. In contrast, the events of the deaths of Iraj and Siyavash, or the tragic division of Jamshid, are not seen as tragic in the same sense. Instead, these figures have followed paths that, whether right or wrong, are the results of their own choices; the choices of a hero in the direction of enhancing existence, or, in other words, in alignment with establishing “Asha.”

In previous lectures, it was noted that the ethical covenant in this epic system is based on a fourfold foundation. Among the two options for goodness, which lie between the extremes of excess and deficiency, it is the wisdom and sense of timing of the human hero that can determine the best course of action for a given situation. For example, between the two extremes of malevolence—“miserliness” and “wastefulness”—choosing one of the two positive options, “generosity” and “economy,” depends solely on the individual’s wisdom and understanding of time, rather than following an unblemished and predetermined directive. This means that the epic thought is a doctrine of choice; a choice that, through “Khwarrah” (the light of divine glory), enters the very essence of each individual and enables them to stand against the constraints of fate, thereby making a secondary unity possible.

In Iranian essence, praise is expressed through festivals, and Yashteh and Yazdan are interconnected. Each festival is based on renewing the deeds of one of the legendary heroes of Iranian epic history. Hoshang established the festival of Sadeh, which celebrates the formation of the concept of the center, and its material element, fire. It is held in honor of life. Yalda, or the winter solstice, is the birth of the deity Mithras, and also marks the birth of the first human. In the story of Kiumars, who represents the myth of the birth of humanity, his seed remains in the heart of the mountain for a winter.

This festival may be one of the oldest rites, and it traveled to distant places with its red symbols among the peoples who migrated from this region to Europe in ancient times. Jamshid established Nowruz as a festival to celebrate existence and creation. Tirgan commemorates the shooting of arrows by Arash and the protection of the land. Another account of this festival involves Kay Khosrow, who, upon seeing the angel Soroush on a mountain in Saveh, loses consciousness and regains it by sprinkling water; thus, water-sprinkling is a ritual of this festival. Fereydun established Mehrgan. Fereydun does not kill Zahhak but binds him; thus, Mehrgan is a rite honoring life. In this way, every month has its festival, and each festival is a return of an epic tale to us.

The concept of “Farah” (or “Divine Glory”) manifests in one of its diverse forms through the symbol of the “Simorgh” (Sina), or what Hafez refers to as “Farrokh.” This Farah radiates from the individual to the collective; from the “individual wisdom” to the “collective wisdom.” It is understood in two aspects: “easy wisdom” and “striving wisdom,” which differ from the Greek notions of logos and reason. Individual wisdom is not subject to the will of the collective, as seen in the divine epics and the Shahnameh, where heroes do not show absolute obedience to the king (Rostam criticizes King Kaikosro for his whims, and Zal rebukes Kay Khosrow). Heroes think and act according to their own judgment. In fact, wisdom and the wise person consist of choosing truth and goodness, or “synergy” and “alignment” with “Rata” (truth). What constitutes the essence of wisdom and heroism is the choice of goodness (Khurreh + Rata). This choice is possible under the illumination of wisdom, and hence, is associated with light; “enlightened opinion” cannot be achieved without relying on wisdom.

In heroic thought, the expansion and continuation of “Asha” (truth, goodness, justice), meaning its establishment in a system referred to as “Arta” (the norm of existence), does not require the separation of celestial and terrestrial actions. Nature is seen as a reality itself, and this thought does not subscribe to metaphysics. In this paradigm, the concepts of “Yasht” and “Yazdan,” or “festival” and “praise,” are not concerned with the “supernatural,” but rather focus on “actual reality,” making this understanding possible for people through the “experience of joy.”

Fetawat-namas (Book of Chivalry) consist of a collection of spiritual and chivalric principles and rules. The various existing treatises share many common features, and all emphasize that Fetawat is the revival of innate purity and initial glory. The rites of initiation, the rituals of joining the Fityan (chivalrous men), and their internal, often secretive and mysterious hierarchical structures continue an ancient tradition rooted deeply in the Mithraic religion up to the later periods.

The chivalric practices and the support of the Soshiants (saviors) are based on the idea that the Faravahar or Farah comes to this world to assist Ahura Mazda in the battle against the demonic darkness. Najm al-Din al-Zarkub stated in his work Sera al-Rububiya: ‘God and His chivalrous servants cannot live without each other.’

The term Mithra refers both to the sun and to ‘love,’ synonymous with friendship. Joining the followers of Mithra signifies entering into a bond of friendship, regularly renewed through ceremonial feasts, symbolizing the rebirth of humanity.

The treatises on chivalry provide details about joining and living according to this tradition and method.

At a crucial historical juncture, the tradition of chivalry, or Fetawat, played a role in establishing a civil system. The founding of Zourkhanehs (traditional Iranian gymnasiums) and the joining of men to the circles of chivalrous individuals came after the fall of national governments, at a time when the conquering forces had neither the motivation nor the intent to protect the lives, property, and honor of the people. This new form was more than just a pastime or sport. It relied on ancient models of architecture, music, poetry, and physical training to create a mechanism for safeguarding the lives, property, and security of people in cities. The strength of these circles lay in the elements that connected them to other rites, ethical models, and the esteemed notion of chivalry in the cultural ethos.

The Emergence of Epic Thought in the Inquiry of Humanity, Existence, and Time

Perhaps the most decisive answer to the question of ‘time’ is that it allows us to measure ‘what is’ and liberates time from an unnamed, inconspicuous, and endless cycle. 12 Understanding time in Iranian thought can be found in the concept of ‘farashgard,’ meaning continual renewal; in this culture, the world is in a perpetual state of ‘farashgard.’ Under such a view of existence, the flow of ‘time’ is understood as ‘eternal present.’ According to some linguists, this characteristic is reflected in the structure of colloquial Persian, where the present tense is often used even to convey concepts related to the past and future. Similarly, in some ancient texts, such as the Yadgar-e Zariran, one of the most significant epic reference texts, conversations all occur in the present tense, and the actions are expressed in the present tense. 13 Outas, a linguist, has specifically noted the use of verbs in this text.14

This understanding of the present time is not only evident in literary language but also in other arts. For instance, in Persian miniature painting, colors are typically without shadows; shadows signify the passage of everyday time, which disrupts this perception of time and darkens the mind. In the realm of the epic present, all events are before us, and heroes from distant history are present to us. In the Khawaran-nama of Ibn Hisham, epic heroes like Rostam and the first Imam of the Shi’a are depicted as existing simultaneously, and in similar performance scenes, all narratives are represented within a single setting.

Among the Iranian festivals, meanings related to the nature of temporal understanding become apparent; each celebration marks the beginning and end of an event connected to an epic narrative, and each time it is renewed in the present moment of its celebrants.

The answer to the question of ‘humanity’ will also be influenced by the cultural understanding of existence and the system that has given meaning to it. In Greek epics, humanity is defined in relation to the gods, with limited emphasis on human will in making choices. The Christian narrative, on the other hand, involves God entering history; Christianity tells the story of God’s suffering as He bears the burden of human sin. In this narrative, the human soul is believed to attain freedom through the grace of the Holy Spirit.

In the Iranian worldview and its epic narrative of existence and creation, humanity itself is the forgiver and possesses the grace of the divine, or baga, akin to the divine forgiveness of Ahura Mazda. Humans have entered the arena of history not for redemption from sin but to partake in a grand endeavor to realize the beauty of the cosmos. Human presence in the world is not seen as a fall, but rather as an active participation in the ongoing quest to perfect and beautify the universe.

Epic traditions are entirely dedicated to celebrating the exalted nature of humanity. Even mourning for the fallen heroes endowed with divine grace is a tribute to their free choice in confronting manifestations of evil. Thus, it is of no concern if national epic narratives do not necessarily recall victories but also provide detailed accounts of defeats; in this understanding of existence, absolute victory is not the final point. Therefore, stories such as the death of Jamshid and the rise of Zahhak, the deaths of Siyamak and Iraj and the onset of national conflicts, and the demise of the great general Rustam Farrokhzad are among the most revered. These narratives remind us that after each defeat, the heroic spirit finds the opportunity to rise again, and their repeated recounting underscores how divine grace will persist in the world.

In this ideology, the ideal city or “City of Goodness” is hidden within the core of the original creation of the cosmos and is a trust that emerges through humanity’s struggle to establish the norms of existence. In this concept, “the end of time” is not a utopia that emerges through the destruction of the world but occurs through the renewal of the cosmos, a renewal that is continually happening. “Moment” embodies the continuous renewal of the present time. The renewal of the cosmos, achieved by humans, is embodied within the confined space of the “garden”; in the prologue of the Golestan, a precise image of the Iranian heroic spirit is succinctly drawn from Saadi’s thoughts, focusing on the moment, the gratitude for the beauty of the cosmos, and ultimately the theme of the garden.

Consider the moment a treasure, for the world is but a moment.

He who is companion to the moment, truly is Adam.

Seek the moment from me, for Adam is revived by it.

The grace of this moment encompasses the world within the world.

Moment by moment, and breath by breath, I shall be your friend.

In this era, I am the master of the breath.

Indeed, in every era, I am the sovereign of the soul.

I am the gateway of knowledge and the point of mysticism.

That which cannot be conceived in imagination, is me.

Safi Ali Shah

In this arena, the human-hero continually faces impurity, drawing demonic forces out of their hiding places. “Death on the battlefield is considered more disgraceful than honorable, thus the death of a hero in great epics is often heroic, such as the deaths of Zarir or Bahram. 15

The climax of these sentiments in the epic narratives of Iran is the story of Arash the Archer, which is unparalleled among all the epics of the world. This narrative is not found in the Shahnameh but is mentioned in the Yasts, demonstrating the profound nature of ancient Iranian epics. In fact, the Yasts clearly show that in ancient Iranian epics, the role of deities was prominent. In the Yasts themselves, there is no direct intervention by deities in human affairs, nor do deities possess human-like traits. Unlike the Greek gods, who often exhibit multiple personas, these deities are consistently supportive of deserving heroes, legitimate kings, and righteous deeds. 16

In contrast to ‘tragedy,’ the realm is the embodiment of Prometheus. In Greek thought, Prometheus steals fire from the gods and brings it to earth, positioning humanity in its place before the gods. However, what makes this confrontation tragic is human destiny, which is beyond human control and predetermined. ‘Tragedy is the plight of individuals who purify sin by shedding their own blood.’ 17

These deep-rooted and resilient concepts continue to endure; in the modern era, Prometheus emerged from the depths of history and challenged a thousand years of Christian sin, taking shape in Faust. In the depths of Faust’s spirit, the concept of ‘sin,’ inherited from ancient culture to European Christianity, remains alive in contrast to the Greek Prometheus. The idea of human fallenness in Plato’s thought and also in ancient culture reemerged in a new form as Marxist messianism.

In contrast, in the epic thought, the belief in a predetermined fate, which contradicts justice and goodness, is condemned. Here, the ultimate fate of the body or matter is not subjugation, but ‘in this idea, matter and meaning will achieve an ideal unity. Thus, denying the fundamental goodness of the material world is incorrect, and attributing the world to evil and sin is unacceptable.’ 18

In ancient cultures, the entrance and threshold of a place often held special significance. Entering any space was accompanied by specific rituals, and the roles of gatekeepers and doorkeepers were considered important positions. Therefore, the design of thresholds, doors, and city gates typically contained symbols that reflected the spirit of each culture.

In Iranian architecture, entrance doors are often designed according to the overall plan of the garden and its main axes. Comparing two examples of entrance designs—one from the entrance door of the Chahar Bagh School in Isfahan and the other from the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral—both of which are prominent examples in this field—can illustrate the difference between the heroic and tragic spirits.

On the other hand, this world, which is a creation of goodness, can also be a battleground of good and evil. Therefore, in the Iranian cosmology, eschatology and the afterlife are not focused on waiting for the ‘end of the world,’ but rather on striving for the ‘reconstruction of the world.’ Contrary to the views of some European Iranologists, in the Iranian worldview, the concept of ‘prophecy,’ as understood in the ancient cultural center, does not exist.

‘Zoroaster speaks of two mīnu (ways of thinking); ‘Spenta Mīnu’ and ‘Angra Mīnu,’ which were initially one ‘good’ and the other ‘bad’ in thought, speech, and behavior. When these two mīnu came together, they first established ‘life’ and ‘non-life,’ and thus it will be until the end of existence. The reward for the righteous is ‘heavenly mīnu’ = the best state of mind, and the punishment for the wicked is ‘hell’ = a bad existence.’ (Yasna 30 – Verse 3)’ 19

Here, the human psyche is engaged in confrontation and dialogue with existence. The heroic human sees himself as effective and autonomous in influencing and shaping the cosmos. A defining characteristic of humans is their capacity for choice, with the central theme not being submission or obedience. This fundamental difference contrasts with the concepts found in the Gathas, ancient religions, Greek myths, Hindu traditions, and Chinese Daoism.

In this worldview, wisdom is the creator of things (and is associated with Humen), and thinking is the essence of being human. Understanding the concept of “existence and non-existence” is not possible without the awareness gained through thought. Thus, “being human is an understanding of time inherent in our nature, and Ahura Mazda, as the creator of the world, is aware of it, rather than the world itself. The time created by Ahura Mazda, which is confined, is set into motion with the help of the spirits of the righteous.” 20

In a tradition that continues to this day, Hindu women draw an intricate and colorful mandala on the ground at the entrance of their homes or ashrams each morning using flour or colored powders. These detailed, yet ephemeral designs are created anew each day and fade by evening, serving as a reflection of this particular awareness of the world’s order.

The human-hero is a free being endowed with the divine gift of wisdom, which brings forth the “generative thought of existence” from abstraction. His distinctive quality is the ability to make free choices between existence and non-existence, and between good and evil. Being blessed with divine favor comes from living virtuously in the world and contributing to its advancement. The human-hero resolves the conflict between the world (giti) and the divine (minu); goodness acquires the meaning of “truth,” and truth in action and conduct translates to “prosperity.” The concept of “battle” transcends mere conflict, defense, and assault, evolving into a struggle of cosmic scope, directed towards the spiritual evolution.

Let’s take another look at the depiction of the kingly glory on the wall of the studio, having reached the end of this worldly battle, with an empty quiver and his bow resting on the ground.

“Let us not consign the world to evil, / But strive with all hands for goodness. / Neither good nor evil is everlasting, / Better that goodness be remembered.”

In the inscriptions of the Persian tradition, there are numerous references to human conscience (khe, the world) and the “inner judgment” of individuals. In the arena of the world, the inner dialogue of the human-hero, guided by the measure of wisdom, is linked with the concept of the “ideal city” and the land of happiness. The human bearer of this ideal city has its divine essence from the beginning and not the end, and he can be the bearer, builder, and guardian of this city of goodness in the world. This means that the past is not behind the human-hero but rather beneath his feet. Thus, in Persian epics, the ancestors, the virtuous, and the heroes are present with us or emerge from the expanse of history into our present.

The creation of the world and existence is not a fall but an epic endeavor, with Iran being its central realm and the stage for this grand battle.

The human being is the sole heir of the divine wisdom of Ahura Mazda, and for this reason, he is the only being endowed with free will in the world; that is, he is inherently free. He is a chooser and, in the light of wisdom, can freely select between existence and non-existence. Therefore, in the Persian epic worldview, the motivation for righteous action is not the display of servitude to God, but rather the necessity of assisting Him in the struggle against Angra Mainyu (Ahriman) and achieving victory over it.

The subconscious projections of every nation and people permeate their games and amusements. If in Mediterranean cultures confrontation is viewed as warfare, the elimination of the loser, and the supremacy of the victor, this perspective is also reflected in their traditional games. Card games, for instance, are debates between two or more players that end with one player winning and the other being eliminated. Furthermore, the rules of these games have a tragic logic; with the random distribution of cards, each hand seems to start with a predetermined fate or “Moira.” A player may initially have the upper hand but can unexpectedly be eliminated, and typically, the eliminated player has no return.

In contrast, the spirit of games in Iranian culture, such as chess and backgammon, is different. Fate does not play a predetermined role in these games; rather, victory depends more on the skill and strategy of the players. It is common in these games for a piece to be removed from the board, but there are usually ways to return it to play, and strategies for reviving the game. Archaeological research has uncovered numerous artifacts related to board games in regions such as Jiroft, Burnt City, Zabol, Mohenjo-Daro, and along the Indus, which are predecessors of chess and backgammon.

Similarly, the game of polo, which was played in the largest urban arenas, serves as a metaphor for the hero who must skillfully and purposefully guide the ball to its destination.

“Behold, the celestial sphere is bending under the weight of your polo stick / The realm of the cosmos and the field of play are yours.” —Hafez

Government of the soul and spirit

The phrase “Government of the soul and spirit” is a very significant topic, which Dr. Javad Tabatabai elaborates on in his book Nation, State, and Rule of Law:

“From the very beginning of the establishment of the Persian Empire, this ‘Government of the soul and spirit’ provided a fate distinctly different from what the Old Testament scriptures had outlined for the children of Israel. Cyrus’s conduct in Babylon not only contrasts sharply with the violent actions of the prophets of the Old Testament, but it also stands in direct opposition to the violence perpetrated by those prophets.”

This negative approach to war among the people of Iranshahr has historically been one of their most significant behavioral models. This model led them, at times, to be poor warriors and, in many instances, to be unable to defend their country as effectively as they should have.

Nevertheless, this pacifistic approach, in addition to influencing their personal behavior, has had a profound impact on the collective fate and culture of the people of Iranshahr. It has shaped their conduct in a distinctive way. The origin of this different approach to war, undoubtedly, lies in the ancient Iranian traditions.

Although there is no single consensus among historians regarding Cyrus the Great’s religious beliefs, there is no doubt that Cyrus the Great revered Ahura Mazda and adhered to the principles of his faith, which include good words, good deeds, and good thoughts.

This behavioral paradigm continued even after Iranians converted to Islam, manifesting in various forms, one of the notable aspects being the persistence of this spirit of reconciliation and tolerance in Persian literature. Even the national epic of the Iranians is not a document of war but rather a reflection of the wisdom of a people who do not resort to cruelty in battle. The national epic is a form of poetic expression and one example of Persian literature. Other forms of Persian literature each reflect aspects of the spirit that has dominated Iranians since ancient times and provides a foundation for the concept of “government of soul and spirit.” 21

The concept of “government of soul and spirit” took root in the life of the Iranian peasant in ancient times and continued to proliferate for millennia. The methods adopted for sustaining life did not encourage an aggressive temperament, reflecting the geographical reality of the land, which did not offer opportunities for raids, plundering, or seeking refuge in secure fortresses. This land has always been situated in the midst of the world, and its continued existence necessitated an invitation to coexistence, tolerance, and mutual respect.

Heroic rituals are entirely dedicated to celebrating the nobility of the hero-warrior. Even mourning for illustrious heroes serves to honor their free choice in battling an aspect of evil. Thus, it is of little concern that these narratives do not necessarily emphasize victories; indeed, the history of defeats is highly esteemed. The bards have sung laments for Siyavash and the memorial of Zarir, and centuries later, the passion plays for the martyrdom of the Imams were performed, all serving to keep a memory alive. The underlying message is that, after every defeat, the heroic spirit finds the possibility of resurgence. This recurring narrative reminds us of how the divine grace in the world will endure.

Sources:

- Khalighi-Motlagh, Jalal (2007). Epic: A Comparative Phenomenology of Heroic Poetry, Dār al-Ma’arif-e Bozorg-e Eslāmi Publications.

- Khalighi-Motlagh, Jalal, and Ali Dehbashi (2009). Ancient Sorrows: Selected Articles on Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, Nashr-e Salis.

- Khalighi-Motlagh, Jalal, Mahnaz Moghaddasi, and Hooman Abbaspour (2019). Footprints of the Years: Twenty Essays on Shahnameh, Persian Literature, History, and Iranian Culture, Hamisheh Publications.

- Maskub, Shahrukh (2005). The Legacy of the Past: An Essay on Shahnameh, Nashr-e Ney.

- Tabatabai, Javad (2019). Nation, State, and Rule of Law: An Essay on Text and Tradition, Minoo Khord Publications.

- Moghadam, Mohammad (2001). An Essay on Mithra and Anahita, Nashr-e Hirmand.

- Navabi, Yahya Mahyar. The Legacy of Zariran, Nashr-e Asatir.

- Hinz, John Russell (1989). Understanding Iranian Mythology, Translated by Zahra Amuzgar and Ahmad Tafvizi, Nashr-e Cheshmeh.

- Behruz, Zabih. Script and Culture, Iran Koudeh, Issue 8.

- Carbon, Henri (2004). The Rites of Chivalry, Translated by Ehsan Naraghi, Nashr-e Sokhan.

- Carbon, Henri (2017). The Kingdom of the Divine: The Body of Man on the Day of Resurrection from Zoroastrian Iran to Shiite Iran, Translated by Inshallah Rahmati, Nashr-e Sofia.

- Bahar, Mehrdad (1976). Cultural-Social Study of Tehran’s Zurkhanehs, Supreme Council of Culture and Art.

- Bo, Utas (1975). On the Composition of the Ayyatkar i Zareran.

- Grabar, Oleg et al. (2013). Shahnameh and Recent Research on Historical Painting, Art, and Iranian Society, Translated by Fazli Birjandi, Nashr-e Payan.

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1968). Old Iranian Literature, Handb.d. Orient. 4. Bd. Iranistik, 2. Absch. Literatur, Brill.

- Driver, G.R. (1957). Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B.C., Oxford.

Footnotes:

- Examples such as the revival of pre-Christian epic narratives and the subsequent blending of music with an epic story (like Wagner’s “Nibelungen”) only occurred in the modern era, during a time when the German nation was undergoing the historical experience of shaping its national identity. This period was marked by many German thinkers turning away from Christianity—such as Hölderlin, Fichte, and Hegel (before Jena)—and the continuation of this trend in Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Wagner.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal (2007).

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal (2007).

- Evidence for this claim includes some rare examples such as papyri found in Egypt written in Aramaic, some of which date back to the fifth century BCE. Among these, a copy of the Darius inscription at Behistun can be found (the stone inscription itself refers to these copies as “prešahwāda”). There is no doubt that this was not the only copy of the inscriptions written on less durable materials, but rather an example that has accidentally survived and reached us. It is also clear that before the lines were engraved on stone, the original text would have been carefully drafted by scribes and presented to the king. Subsequently, translators would have translated it into Persian, Akkadian, and Elamite, and provided it to the stonecutters for engraving. For more on these pieces, refer to: Driver, G.R. 1957 and Gershevitch, Ilya 1968.

- The Shahnameh, as a great legacy of the Persian language and literature, has a multifaceted structure. At times, it resembles a tragedy, and in other parts, it approaches dramatic language with direct and intense dialogues. This contrasts with the slow-moving epic style, as it progresses rapidly toward its goals with a language that conveys action rather than mere narrative. Ultimately, it is not easy to categorize the characteristics of the Shahnameh, which goes beyond being a literary work to explain the culture and thought of Iran, within the conventional terms of classification. Since the term “epic” in its precise sense today refers to “narrative poetry,” as opposed to “lyric” meaning “elegiac poetry,” an epic poem is one that praises heroic deeds. However, epic sequences and “great narrative poems” that exist only in some literary traditions of the world are categorized under EPOS in modern terminology. This means that EPOS is an evolved form of lyrical poetry, encompassing praise of valor and larger, independent epic pieces. For further reading, refer to the articles by Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal.

- Moghadam, Mohammad.

- For further study, refer to the research of Oleg Graber and Ulrich Marzolf.

- For further reading, consult the articles by Mehrdad Bahar.

- This hierarchy typically ranges from novice, to hero, mentor, and the hero with the bell.

- Traditional accounts of the Zurkhaneh tradition recognize Pouriya-ye Vali as the founder of this system, who lived during the time of the Turkic invasions.

- Moira comes from the verb moir, meaning “to divide.”

- Maskoub, Shahrokh (2005).

- This epic drama originally had an Avesta form and, due to its significance, is among the works that have been transmitted through the Persian era. It was apparently a combination of prose and poetry but is now available in its current form in the Pahlavi (Sassanian) language and script. In this text, one can observe the structures and combinations of the Parthian language, and only a poetic reconstruction of some sections is possible. Professor Geiger was one of the first researchers to translate this text into German as “The Legacy of Zariran” in 1890, comparing and aligning several passages with Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. He correctly identified that this text was also known as the “Shahnameh of Gushtasp,” which is why this manuscript is also called the Shahnamek in Pahlavi. (Quoted from Yahya Mahyar Nawabi.)

- Utas, Bo (1975) rightly points out that all the verbs in the story should originally be in the present tense. Like Benveniste (Émile Benveniste), he considered the text to be in verse. In 1976, he also wrote a detailed article on the verbs and verb prefixes in this text.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Jalal.

- Hinz, John Russell (1989).

- Moghadam, Mohammad (2001).

- Maskoub, Shahrokh (2005).

- Tabatabai, Javad (2019).

فرم و لیست دیدگاه

۰ دیدگاه

هنوز دیدگاهی وجود ندارد.